Superficial Fungal Infections

KEY CONCEPTS

![]() Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is a fungal infection of the vagina that can be classified as uncomplicated or complicated. This classification is useful in determining appropriate pharmacotherapy.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is a fungal infection of the vagina that can be classified as uncomplicated or complicated. This classification is useful in determining appropriate pharmacotherapy.

![]() Candida albicans is the major pathogen responsible for VVC. The number of cases of non–C. albicans species appears to be increasing.

Candida albicans is the major pathogen responsible for VVC. The number of cases of non–C. albicans species appears to be increasing.

![]() Signs and symptoms of VVC are not pathognomonic, and reliable diagnosis must be made with laboratory tests including vaginal pH, saline microscopy, and 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy.

Signs and symptoms of VVC are not pathognomonic, and reliable diagnosis must be made with laboratory tests including vaginal pH, saline microscopy, and 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy.

![]() C. albicans is the predominant species causing all forms of mucosal candidiasis. Important host and exogenous risk factors have been identified that predispose an individual to the development of mucosal candidiasis. In oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis, the key risk factor is impaired host immune system.

C. albicans is the predominant species causing all forms of mucosal candidiasis. Important host and exogenous risk factors have been identified that predispose an individual to the development of mucosal candidiasis. In oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis, the key risk factor is impaired host immune system.

![]() A topical antimycotic agent is the first choice for treating oropharyngeal candidiasis. Systemic therapy can be used in patients who are not responding to an adequate trial of topical treatment or are unable to tolerate topical agents and in those at high risk for systemic candidiasis. Fluconazole and itraconazole are the most effective azole antimycotic agents.

A topical antimycotic agent is the first choice for treating oropharyngeal candidiasis. Systemic therapy can be used in patients who are not responding to an adequate trial of topical treatment or are unable to tolerate topical agents and in those at high risk for systemic candidiasis. Fluconazole and itraconazole are the most effective azole antimycotic agents.

![]() For esophageal candidiasis, topical agents are not of proven benefit; fluconazole or itraconazole solution is the first choice.

For esophageal candidiasis, topical agents are not of proven benefit; fluconazole or itraconazole solution is the first choice.

![]() Optimal antiretroviral therapy is important for the prevention of recurrent and refractory candidiasis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Optimal antiretroviral therapy is important for the prevention of recurrent and refractory candidiasis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

![]() Primary or secondary prophylaxis of fungal infection is not recommended routinely for HIV-infected patients; use of secondary prophylaxis should be individualized for each patient.

Primary or secondary prophylaxis of fungal infection is not recommended routinely for HIV-infected patients; use of secondary prophylaxis should be individualized for each patient.

![]() Topical antimycotic agents are first-line treatment for fungal skin infections. Oral therapy is preferred for the treatment of extensive or severe infection and those with tinea capitis or onychomycosis.

Topical antimycotic agents are first-line treatment for fungal skin infections. Oral therapy is preferred for the treatment of extensive or severe infection and those with tinea capitis or onychomycosis.

![]() Oral antimycotic agents such as terbinafine and itraconazole are first-line treatment for toenail and fingernail onychomycosis.

Oral antimycotic agents such as terbinafine and itraconazole are first-line treatment for toenail and fingernail onychomycosis.

Superficial mycoses are among the most common infections in the world and the second most common vaginal infections in North America. Mucocutaneous candidiasis can occur in three forms—oropharyngeal, esophageal, and vulvovaginal disease—with oropharyngeal and vulvovaginal disease being the most common. These infections were reported in humans as far back as 1839. Over the past 15 to 20 years, the occurrence rates of some fungal infections have increased dramatically. The prevalence of fungal skin infections varies throughout different parts of the world, from the most common causes of skin infections in the tropics to relatively rare disorders in the United States. This chapter reviews the pharmacotherapy of vulvovaginal candidiasis, oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis, and common dermatophyte infections.

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

![]() Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) refers to infections in individuals with or without symptoms who have positive vaginal cultures for Candida species. Depending on episodic frequency, VVC can be classified as either sporadic or recurrent.1 This classification is essential to understanding the pathophysiology, as well as the pharmacotherapy, of VVC. Furthermore, VVC may be defined as uncomplicated, which refers to sporadic infections that are susceptible to all forms of antifungal therapy regardless of the duration of treatment, or complicated, in which consideration of factors affecting the host, microorganism, and pharmacotherapy all have an essential role in successful treatment.1 Complicated VVC includes recurrent VVC, severe disease, non–Candida albicans candidiasis, and host factors, including diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and pregnancy.1

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) refers to infections in individuals with or without symptoms who have positive vaginal cultures for Candida species. Depending on episodic frequency, VVC can be classified as either sporadic or recurrent.1 This classification is essential to understanding the pathophysiology, as well as the pharmacotherapy, of VVC. Furthermore, VVC may be defined as uncomplicated, which refers to sporadic infections that are susceptible to all forms of antifungal therapy regardless of the duration of treatment, or complicated, in which consideration of factors affecting the host, microorganism, and pharmacotherapy all have an essential role in successful treatment.1 Complicated VVC includes recurrent VVC, severe disease, non–Candida albicans candidiasis, and host factors, including diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and pregnancy.1

Epidemiology

Minimal information on the incidence and prevalence of VVC exists. Healthcare workers are not required to report cases of VVC; therefore, estimates are derived from self-reported histories. Epidemiologic data are limited because VVC usually is diagnosed without microscopy and/or cultures, and antifungal nonprescription preparations are available for self-treatment.1 By 25 years of age, approximately 50% of college women will have had at least one episode of VVC.1 It is rare before menarche and increases dramatically at about 20 years of age, with the peak incidence between age 30 and 40 years. It is associated with the initial act of sexual intercourse. As many as 75% of women experience one bout of symptomatic VVC in their lifetime. Between 40% and 50% of women who experience one episode of VVC experience a second episode, and 5% experience recurrent VVC.2,3 Black women appear to be at higher risk than white women of developing VVC (62.8% vs. 55%, respectively).4 The incidence after menopause remains unknown. However, one study of 149 healthy postmenopausal women with vulvar conditions reported significantly more women taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) were prone to developing VVC than those who were not taking HRT (culture-positive, clinical VVC in 49% on HRT versus 1% on those not on HRT).5

Costs from VVC can be direct (medical visits and self-treatment) and indirect (nonmedical expenses, e.g., time losses from work, costs of travel, and time required in obtaining treatment). There are an estimated 6 million visits to healthcare providers each year, resulting in more than $1 billion spent annually on these medical visits and self-treatment.6

Pathophysiology

![]() Candida albicans is the major pathogen responsible for VVC, accounting for 80% to 92% of symptomatic episodes. The remainder are caused by non–C. albicans species, with Candida glabrata dominating.7 The number of cases of non–C. albicans candidiasis appears to be increasing, possibly related to the use of nonprescription vaginal antifungal preparations and short-course therapy and/or the increased use of long-term maintenance therapy in preventing recurrent infections.1

Candida albicans is the major pathogen responsible for VVC, accounting for 80% to 92% of symptomatic episodes. The remainder are caused by non–C. albicans species, with Candida glabrata dominating.7 The number of cases of non–C. albicans candidiasis appears to be increasing, possibly related to the use of nonprescription vaginal antifungal preparations and short-course therapy and/or the increased use of long-term maintenance therapy in preventing recurrent infections.1

Candida species can act as commensal members of the vaginal flora. Asymptomatic colonization with Candida species has been found in 10% to 20% of women of reproductive age.7,8 Candida organisms are dimorphic; blastospores are believed to be responsible for colonization (transmission and spread), whereas germinated Candida forms are associated with tissue invasion and symptomatic infections.9 To colonize the vagina, Candida species must be able to attach to the mucosa. The attachment process is complex. Not only are candidal surface structures important for attachment, but appropriate receptors for attachment must be present in the epithelial tissue. Not all women have the same range of receptors, which may explain variation in colonization.8 Changes in the host’s vaginal environment or response are necessary to induce a symptomatic infection. Unfortunately, in most cases of symptomatic VVC, no precipitating factor can be identified.9

Risk Factors

Several factors predispose a woman to VVC. VVC is not considered to be a sexually transmitted disease, although sexual factors can be important. There is a dramatic increase in the frequency of VVC when women become sexually active. In addition, oral-genital contact can increase the risk.1 However, current guidelines do not recommend the treatment of asymptomatic partners.7 Contraceptive agents, including the diaphragm with spermicide, the contraceptive sponge, and the intrauterine device, increase the risk of VVC. An in vitro adherence demonstrated that four different isolates of Candida species were capable of adhering to the contraceptive vaginal ring.10 Oral contraceptive users demonstrated increased risk of candidiasis; however, these reports were with the higher-dose oral contraceptive pills, and the risk may not be as great with the lower-estrogen-dose oral contraceptives.11

Antibiotic use can increase the risk of VVC, but it is significant in only a small number of women. The mechanism by which antibiotics can increase the risk of VVC is unknown; colonization, however, is a prerequisite.1 A small pilot study of short course antibiotic use of 3 days of antibiotics increased the prevalence of asymptomatic vaginal colonization of Candida and the incidence of symptomatic VVC.12 Diet (excess refined carbohydrates), douching, and tight-fitting clothing often are listed as important risk factors; however, no association has been established between these factors and increased risk of VVC.1

Clinical Presentation

![]() The clinical presentation of VVC is given in Table 98–1.1,7 These signs and symptoms are not pathognomonic, and a reliable diagnosis cannot be made without laboratory tests. Self-diagnosis has a sensitivity of 35%, a specificity of 89%, and a positive predictive value of 62%.4 More than 50% of women who had self-diagnosed VVC did not have yeast as the causative agent.13 This limits the value of self-diagnosis and the success of self-treatment. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that whenever possible women requesting treatment for VVC should be examined and evaluated. They only recommend self-diagnosis in compliant women with multiple confirmed prior cases of VVC who report the same symptoms. They further recommend that if these individuals fail to improve on a short course of therapy, they be evaluated for a further diagnosis.14 Therefore, in most instances the diagnosis should be based on both clinical presentation and investigations, including vaginal pH, saline microscopy, and 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy. The vaginal pH remains normal in VVC, and microscopic investigations should detect blastospores or pseudohyphae. Candida cultures usually are not required in the diagnosis of uncomplicated VVC; however, they are recommended when an individual presents with classic signs and symptoms of VVC, has a normal vaginal pH, but microscopy is inconclusive or recurrence is suspected.7

The clinical presentation of VVC is given in Table 98–1.1,7 These signs and symptoms are not pathognomonic, and a reliable diagnosis cannot be made without laboratory tests. Self-diagnosis has a sensitivity of 35%, a specificity of 89%, and a positive predictive value of 62%.4 More than 50% of women who had self-diagnosed VVC did not have yeast as the causative agent.13 This limits the value of self-diagnosis and the success of self-treatment. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that whenever possible women requesting treatment for VVC should be examined and evaluated. They only recommend self-diagnosis in compliant women with multiple confirmed prior cases of VVC who report the same symptoms. They further recommend that if these individuals fail to improve on a short course of therapy, they be evaluated for a further diagnosis.14 Therefore, in most instances the diagnosis should be based on both clinical presentation and investigations, including vaginal pH, saline microscopy, and 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy. The vaginal pH remains normal in VVC, and microscopic investigations should detect blastospores or pseudohyphae. Candida cultures usually are not required in the diagnosis of uncomplicated VVC; however, they are recommended when an individual presents with classic signs and symptoms of VVC, has a normal vaginal pH, but microscopy is inconclusive or recurrence is suspected.7

TABLE 98-1 Clinical Presentation of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

TREATMENT

Goals of Therapy

The goal of therapy is complete resolution of symptoms in patients who have symptomatic VVC. A test of the cure is not necessary if symptoms resolve.7 Antimycotic agents used in the treatment of VVC do not meet the definition of being fungicidal agents because of their slower killing rate. At the end of therapy, the number of viable organisms drops below the detectable range. However, by 6 weeks after a course of therapy, 25% to 40% of women will have positive yeast cultures and remain asymptomatic.1 Asymptomatic colonization with Candida species does not require therapy.

General Approaches to Treatment

The approach to therapy is to remove or improve any predisposing factors if they can be identified. A pharmacologic antimycotic agent should have limited local and systemic side effects, a high cure rate, and easy administration. Additionally, it would be advantageous to use a therapy that is able to resolve symptoms within 24 hours, that has broad antimycotic activity (to cover increasing rates on non–C. albicans species), that prevents recurrence, and that can be used over a shortened period of time, such as 1 to 3 days. Many topical azoles medications (such clotrimazole, miconazole, etc) are available without a prescription, and although this may increase public access to these medications, there is concern that having them available without a prescription may lead to inappropriate use. A study conducted using 10 actors as simulated patients who visited 60 pharmacies found that vaginal antimycotics were more likely to be supplied to appropriate individuals as more information was exchanged, if interactions involved a pharmacist, and if questions regarding specific symptoms were used.15

Patients should be advised to avoid harsh soaps and perfumes that can cause or worsen vulvar irritation. The genital area must be kept clean and dry by avoiding constrictive clothing and frequent or prolonged exposure to hot tub use.3 Douching is not recommended for either prevention or treatment.13 Cool baths can soothe the skin.3 The oral use of lactobacillus remains unclear. A small trial of 55 women being treated for VVC showed that the addition of oral lactobacillus to single dose oral fluconazole augmented the cure rate compared to the use of fluconazole alone.16 A trial of a mixture of oral consumption of bee-honey and yogurt showed some efficacy with mycotic cure rates of 76.9% compared to cure rates with antifungal agents of 91.5%.17 Daily ingestion of 240 mL yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus decreased colonization and symptomatic infections of VVC in women with recurrent infections.18 However, a subsequent study showed that the addition of oral lactobacillus to itraconazole therapy in the treatment of recurrent VVC did not confer any additional benefit. This same trial showed that treatment using classic homeopathy was less effective than the use of itraconazole in recurrent VVC.19

Treatment of VVC will be considered to have positive outcomes if the symptoms of VVC are resolved within 24 to 48 hours and no adverse medication events are experienced. Self-assessment of symptom relief is appropriate for most cases of VVC. If symptoms remain unresolved or recur, then further testing and treatment can be required.

Pharmacologic Treatments

Uncomplicated Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Cure rates for uncomplicated VVC are between 80% and 95% with topical or oral azoles and between 70% and 90% with nystatin preparations. Table 98–2 lists available topical and oral preparations for the treatment of uncomplicated VVC. There are many topical nonprescription preparations for the treatment of VVC. No significant differences in in vitro activity or clinical efficacy exist between the topical azole agents.1,3,7,14 The selection of a topical azole antimycotic agent should be based primarily on an individual patient’s preference as to product formulation. Some topical products can cause vaginal burning, stinging, or irritation; conversely, the vehicle used in topical creams or gels can provide initial symptomatic relief.1 Of note, most topical preparations can decrease the efficacy of latex condoms and diaphragms.

TABLE 98-2 Treatment for Uncomplicated Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Oral azoles (such as fluconazole or itraconazole) have been used in the treatment of VVC. Patients may prefer oral therapy because of its convenience.20 Oral and topical therapies are therapeutically equivalent.1 A Cochrane review of 19 trials analyzing 22 oral versus topical antifungal comparisons concluded that there were no differences between the routes in short-term mycologic cure rates. There was a significant difference between long-term cure rates in favor of long-term followup; however, the authors stated that the clinical significance of this finding is uncertain.21

In the treatment of uncomplicated VVC, the duration of therapy is not critical. Cure rates with different lengths of treatment have not demonstrated that one duration of therapy is significantly better.20,21,22 Shorter-duration therapies (e.g., clotrimazole 1-day therapy) consist of higher concentrations of azoles that maintain the local therapeutic effect for up to 72 hours and allow for resolution of signs and symptoms.23 A review of 14 trials that examined 1-day treatments showed less than 7% difference in short-term cure rates or improvement between any two treatments in any two studies and no significant differences in short- or long-term clinical cure rates among 1-day regimens.22 Table 98–2 lists the therapeutic options for the treatment of uncomplicated VVC.

Clinical Controversy…

Complicated Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Complicated VVC occurs in patients who are immunocompromised or have uncontrolled diabetes mellitus.1 These individuals need a more aggressive treatment plan.14 Current recommendations are to lengthen therapy to 10 to 14 days regardless of the route of administration.14 Therapeutic options include those listed in Table 98–2; however, regimens should be continued for 10 to 14 days. A study of oral fluconazole therapy in women with complicated VVC demonstrated that cure rates increased from 67% with single-dose therapy to 80% when the 150 mg dose of fluconazole was repeated 72 hours after the initial dose.24

VVC during pregnancy can be considered complicated because consideration of host factors such as hormonal changes that can affect normal flora are essential in selecting therapeutic regimens. Topical agents are considered to be safe throughout pregnancy. A systematic review of 10 trials demonstrated that imidazole topical agents (such as fluconazole) were more effective than nystatin. Two of the trials showed that treatment for 7 days was more effective than treatments of 4 days or less.25 Oral agents are contraindicated in pregnancy because of the concern for fetal complications. A prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes in 226 women exposed to fluconazole in the first trimester did not indicate increased risk of congenital abnormalities or other adverse outcomes.26 The median dose of fluconazole was 200 mg, with 46.5% of the cohort receiving a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg.27 However, the ACOG recommends avoiding oral therapy, as larger doses of fluconazole have been linked to birth defects.27 Instead, the ACOG recommends a topical imidazole therapy for 7 days.14

Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) is defined as having more than four episodes of VVC within a 12-month period.1,7 Fewer than 5% of women develop RVVC, and its pathogenesis is poorly understood. A proper diagnosis should be obtained to rule out other infections or nonmycotic contact dermatitis. RVVC is best treated in two stages: an initial intensive stage followed by prolonged antifungal therapy to achieve mycologic remission. This was demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial in which women were assigned to receive 150 mg fluconazole daily for 10 days followed by 6 months of either fluconazole 150 mg weekly or placebo. Ninety percent of women receiving both active treatments were symptom free for the 6 months following initial treatment (during the weekly fluconazole therapy), and there were 50% fewer symptomatic episodes in the 6 months following weekly suppressive therapy.28 The Infectious Diseases Society of America stated that there is good evidence from more than one properly randomized controlled trial to recommend 10 to 14 days of induction therapy with a topical or oral azole, followed by 150 mg of fluconazole once weekly for 6 months for recurring Candida VVC.29

Antifungal-Resistant Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Resistance to azole antimycotics should be considered in individuals who have persistently positive yeast cultures and fail to respond to therapy despite adherence to prescribed regimens.1 These infections can be treated with boric acid or 5-flucytosine.30,31 Boric acid is administered as a 600 mg intravaginal capsule daily for 14 days of induction therapy, followed by a maintenance regimen of one capsule intravaginally twice weekly. Boric acid should not be administered orally, as it is toxic. 5-Flucytosine cream is administered vaginally, 1,000 mg inserted nightly for 7 days. The prevalence of C. glabrata is higher in those with diabetes. In a study of 111 consecutive diabetic patients with VVC, 68% had isolates for C. glabrata compared with 28.8% for C. albicans. Those with C. glabrata had significantly higher mycological cure rates with 600 mg of boric acid suppositories for 14 days compared with a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg.32

OROPHARYNGEAL AND ESOPHAGEAL CANDIDIASIS

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), or thrush, is a common and localized infection of the oral mucosa caused by the yeast Candida. Candida albicans, a common oral commensal organism, is the most frequent infecting species. OPC is also referred to as candidiasis (or the more correct but less commonly used term candidosis). The infection may extend into the esophagus, causing esophageal candidiasis.

Microbiology and Epidemiology

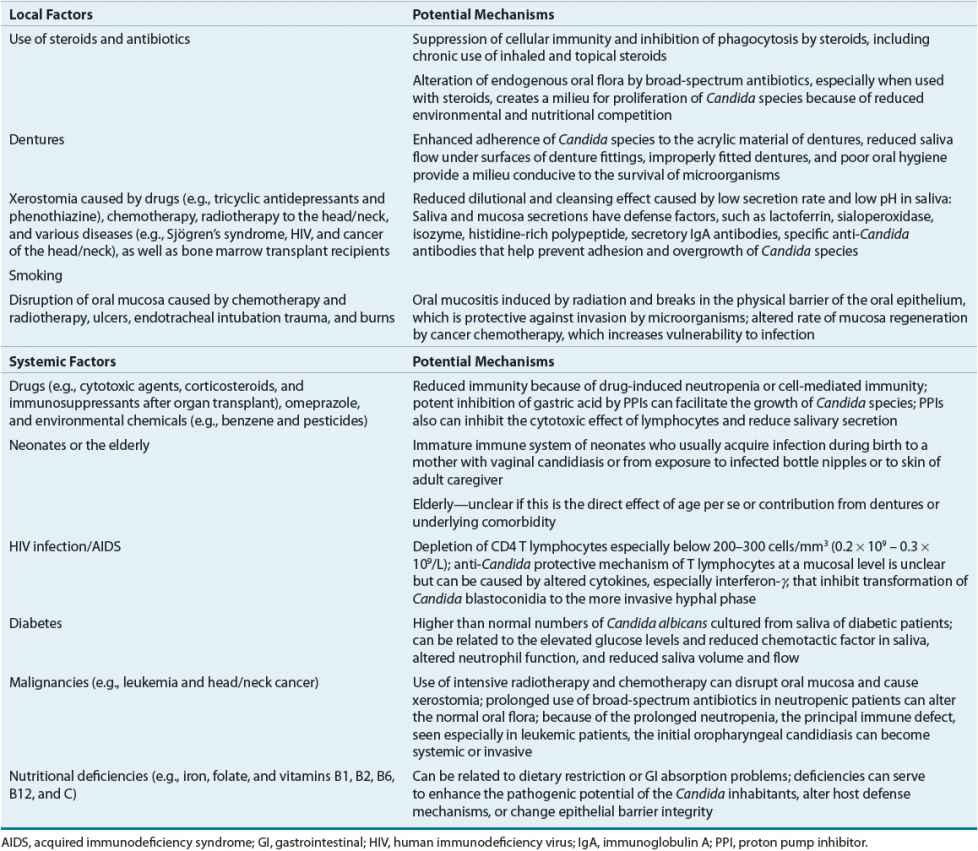

Candida is a commensal fungus found in the oral cavity in up to 65% of healthy individuals with higher prevalence in healthy children and young adults.33,34 Candida carriage increases under immunocompromised conditions and also among hospitalized patients.34 Even in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) up to 80% of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons may demonstrate oral yeast colonization.35 The organism is capable of transition to a pathogen causing symptomatic mucosal infections in association with predisposing host factors.34 Candida albicans is the predominant colonizing Candida species (70% to 80%), but any of the non–C. albicans species can be colonizers. Colonization rates are influenced by the severity and nature of the underlying medical illness and the duration of hospitalization, as well as age (highest in infants younger than 18 months of age and in adults older than 60 years of age). A variety of host and exogenous factors (Table 98–3) can lead to the transformation of asymptomatic colonization to symptomatic disease, such as oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis. C. albicans is the most common species causing all forms of mucosal candidiasis in humans. Less frequently, non–C. albicans species can be pathogenic and cause disease. These include C. glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, and Candida parapsilosis.35,36 Candida krusei, although relatively uncommon, generally is recovered from mucosal surfaces of neutropenic patients with hematologic malignancies.36 Another species, Candida dubliniensis, has been identified in both HIV-infected and noninfected patients, and may cause ~15% of infections previously ascribed to C. albicans.36 In patients with cancer, non–C. albicans species account for almost half of all Candida infections.

TABLE 98-3 Risk Factors for the Development of Oropharyngeal and/or Esophageal Candidiasis

Oropharyngeal candidiasis is the most common opportunistic infection in patients with HIV disease, and it may be the first clinical manifestation of the HIV infection in the majority of untreated patients. OPC occurs in 50% to 90% of HIV-infected patients at some point during the progressive course of the disease to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS),33,35,36 although significant reductions in the incidence have been observed after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. The absolute CD4 T-cell count has been suggested to be the primary risk factor for development of OPC with the greatest risk at CD4 T-cell levels <200 cells/mm3 (<0.2 × 109/L). Also, the HIV viral load has been identified as a predictor of OPC development; OPC is thought to increase with HIV viral loads >10,000 copies/mL (>10 × 106/L). This finding correlates with the observation that initiation of antiretroviral therapy and subsequent increase in CD4 T-cell counts does not fully account for the decrease in OPC incidence.35 Regardless of the CD4 T-cell count, or HIV viral load OPC is predictive for the development of AIDS-related illnesses if left untreated.33,36

In non-HIV diseases, such as cancer, the incidence of OPC varies depending on the type of malignant neoplastic disease, level of immune suppression, and type and duration of treatment, but it is less common than in HIV-infected patients. OPC was initially reported in ~25% of patients with solid tumors and up to 60% in those with hematologic malignancies or bone marrow transplant recipients.37 Current rates of OPC have decreased significantly in these patients because of widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis. Incidence in other patient populations predisposed to OPC such as the hospitalized patient administered broad-spectrum antibiotics or denture and other oral appliance users is not well quantified, however, do represent at-risk individuals where the clinical pharmacist has an important patient-care role.34,37

OPC can predispose patients to develop more invasive disease, including esophageal candidiasis.37 The esophagus is the second most common site of GI candidiasis. The prevalence of esophageal candidiasis has increased mainly because of the number of individuals with AIDS, as well as the increased numbers of other severely immunocompromised patients, especially those with hematologic malignancies.36 Esophageal candidiasis is the first opportunistic infection in 3% to 10% of HIV-infected patients and is the second most common AIDS-defining disease after Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia.36 The mean incidence of esophageal candidiasis among HIV-infected patients is less than OPC and ranges from 15% to 20%.36 The risk of esophageal candidiasis is increased in HIV-infected patients when the CD4 T-cell count has dropped below 100 to 200 cells/mm3 (0.1 × 109 to 0.2 × 109/L), as well as in those with OPC.37,38 However, the absence of OPC does not necessarily exclude the possibility of esophageal disease. Like OPC, the presence of esophageal candidiasis can help predict HIV disease progression and prognosis.37 The incidence of esophageal candidiasis in non-HIV-infected immunocompromised patients is not well established. Candida albicans is the most common cause of esophageal candidiasis, accounting for ~80% of cases, with the rest being caused by non–C. albicans species.35

The introduction of HAART appears to have resulted in a significant decline in the incidence of OPC and esophageal candidiasis.35,36 In addition, the widespread use of the azole agents for treatment and prophylaxis has led to a decline in the prevalence of mucosal candidiasis while leading to the emergence of refractory infections that are more challenging to treat.

Pathogenesis and Host Defenses

The pathogenesis of OPC is most clearly elucidated in the setting of HIV infection. There appear to be several levels of immune defense against the development of OPC in HIV-infected persons, and they involve both systemic and local immunity. The primary line of host defense against C. albicans is cell-mediated immunity (CMI) at the mucosal surfaces, which is mediated by CD4 T cells.33 The efficacy of the CD4 T cells is reduced when the number of cells drops below a protective threshold, and protection against infection becomes dependent on secondary or local immune mechanisms.33,35 When the number of CD4 T cells drops too low, recruitment of these cells to the oral cavity is impaired. The CD4 T-cell count has been considered as the hallmark predictor for development of OPC. However, HIV viral load may have a stronger association with OPC than CD4 cell number.35,39 The possibility that HIV plays a strong role in susceptibility to infection is supported clinically by the observation that OPC is more common in HIV-infected persons than in those with similar immunosuppression, such as lymphoma and bone marrow transplant. When the primary line of defense fails, the secondary host defenses become crucial. These include the CD8 T cells, salivary cytokines, and other innate immune cells, such as the neutrophils, macrophages, and epithelial cells (with anti-Candida activity). Deficiencies or dysfunction in any of these can result in increased susceptibility to OPC. The problem with the CD8 T cells is caused more by a dysfunction of the microenvironment, specifically, reduction in the E-cadherin adhesion molecule that promotes migration of the cells through mucosal tissues.36 The role of humoral immunity by antibodies as a protective mechanism is unclear and controversial. The changeover of the role of Candida species from commensal to pathogenic in the human host usually occurs when breakdown in these host defenses occurs. The pathogenesis of OPC is still not completely understood. It is important to develop a better understanding of the pathogenesis and role of host defenses, including the mechanism of CD8 T-cell activity, reduced adhesion molecules, and whether other cofactors, such as HIV viral load, HAART, and injection drug use, play a role. Immunotherapeutic modalities can then be developed to eliminate the susceptibility factors and significantly reduce OPC in the at-risk populations.

Significant differences exist in the virulence among Candida species in mucosal candidiasis. One virulence factor is the ability of the organism to adapt and survive in response to changes in the host environment.35 The genes required for virulence are regulated in response to the environmental signals indigenous to the host environment (e.g., temperature, pH, osmotic pressure, iron and calcium ion concentrations, oxygenation, and carbon and nitrogen availability). The ability of C. albicans to undergo reversible morphologic transition between the budding pseudohyphal and the more invasive hyphal growth forms is also a determinant of virulence, and genes are recognized to play a role.33 Other virulence factors are the adhesive ability of C. albicans to epithelial cells and proteins and its ability to invade host cells by means of phospholipase and proteinase enzymes. This may be one of the factors leading to OPC in non–HIV-infected individuals. Other components of the pathogenesis in the absence of HIV that have been postulated are the ability of the Candida species to adhere to buccal epithelial cells. A close correlation between adhesion of Candida species and their ability to cause infection has been demonstrated in animal model studies.40 This is hypothesized to be a key element in the development of OPC in patients with altered microflora, including those receiving broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy.

Risk Factors

![]() Several host and exogenous factors contribute to the ability of Candida species to cause infection (see Table 98–3). Local and systemic factors, as well as characteristics of the organism itself, can increase the susceptibility of an individual to Candida infections.33 Endocrine disorders besides diabetes mellitus, such as hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, and hypoadrenalism, also can predispose patients to Candida species overgrowth. Patients with primary immune deficiencies such as lymphocytic abnormalities, phagocytic dysfunction, immunoglobulin A (IgA) deficiency, viral-induced immune paralysis, and severe congenital immunodeficiencies are also at risk for oropharyngeal candidiasis as well as disseminated candidiasis. Oral mucosal disease, such as lichen planus, can be preexistent causes of candidiasis. Smoking has been suggested as a predisposing risk factor. In many cases, multiple concurrent predisposing factors to candidiasis can exist, for example, xerostomia with mucositis and a break in the epithelial surface or immunosuppression, such as might occur in a leukemic patient receiving radiation and chemotherapy. The severity and extent of Candida infections increase with the number and severity of predisposing risk factors.34

Several host and exogenous factors contribute to the ability of Candida species to cause infection (see Table 98–3). Local and systemic factors, as well as characteristics of the organism itself, can increase the susceptibility of an individual to Candida infections.33 Endocrine disorders besides diabetes mellitus, such as hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, and hypoadrenalism, also can predispose patients to Candida species overgrowth. Patients with primary immune deficiencies such as lymphocytic abnormalities, phagocytic dysfunction, immunoglobulin A (IgA) deficiency, viral-induced immune paralysis, and severe congenital immunodeficiencies are also at risk for oropharyngeal candidiasis as well as disseminated candidiasis. Oral mucosal disease, such as lichen planus, can be preexistent causes of candidiasis. Smoking has been suggested as a predisposing risk factor. In many cases, multiple concurrent predisposing factors to candidiasis can exist, for example, xerostomia with mucositis and a break in the epithelial surface or immunosuppression, such as might occur in a leukemic patient receiving radiation and chemotherapy. The severity and extent of Candida infections increase with the number and severity of predisposing risk factors.34

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

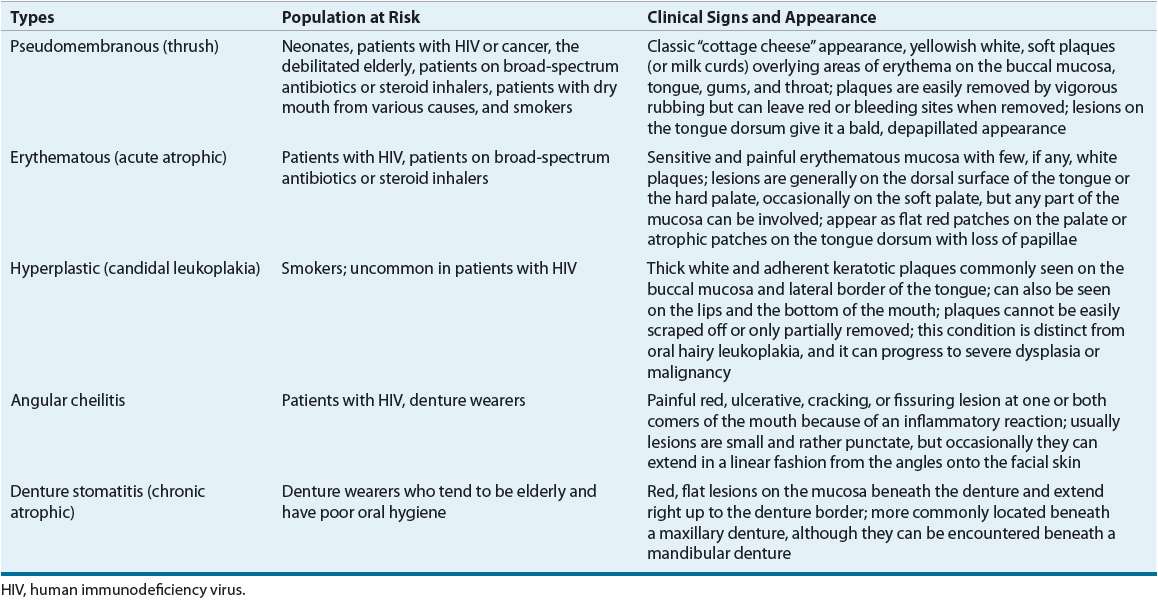

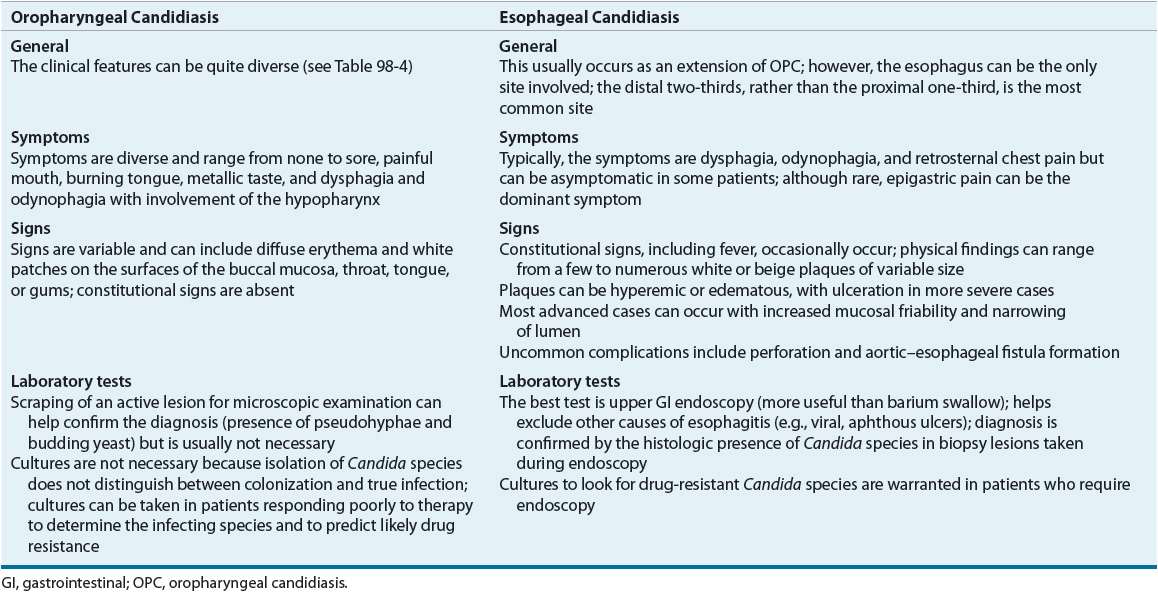

Oropharyngeal candidiasis can manifest in several major forms (Table 98–4).33,34 The clinical signs and symptoms of OPC and the locations of the lesions can be quite diverse (Table 98–5). A presumptive diagnosis of OPC usually is made by the characteristic appearance on the oral mucosa, with resolution of signs and symptoms after antifungal therapy. Pseudomembranous candidiasis, commonly known as oral thrush, is the classic and most common form seen in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent hosts. Erythematous and hyperplastic candidiasis and angular cheilitis occur less commonly in the HIV-infected population. Dysphagia, odynophagia, and retrosternal chest pain are common complaints of esophageal candidiasis, which is usually, but not always, accompanied by the presence of OPC. Clinical symptomatology, along with a therapeutic trial of antifungal, can provide a reliable presumptive diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis. If antifungal therapy does not lead to resolution, more invasive tests such as upper GI endoscopy can be undertaken.

TABLE 98-4 Clinical Classification of Oropharyngeal Candidiasis

TABLE 98-5 Clinical Presentation of Oropharyngeal and Esophageal Candidiasis

TREATMENT

Desired Outcomes

The primary desired outcome in the management of OPC is a clinical cure, that is, elimination of clinical signs and symptoms. Even when the patient is relatively asymptomatic, it is important to treat the initial episode of OPC to avoid progression to more extensive disease. In the most severe cases, the patient’s quality of life can be impaired; this can result in decreased fluid and nutritional intake. Lack of appropriate treatment of OPC can lead to more extensive oral disease, especially in patients who are immunocompromised. The most serious complication of untreated OPC is extension of the infection to esophageal candidiasis. Because esophageal candidiasis is more debilitating, the patient’s quality of life is more affected. It is important to initiate appropriate antifungal therapy for both OPC and esophageal candidiasis. Preventing or minimizing the number of future recurrences of both types of candidiasis is an equally important outcome. The approach depends largely on the underlying predisposing conditions. Mycologic cure is not a necessary treatment outcome because it may not be feasible or realistic, given that Candida species exist commonly as part of the normal mouth flora.

Minimizing toxicities and drug–drug interactions of systemic antifungal agents, as well as maximizing adherence by ensuring that the patient understands the importance of therapy and the directions to take the medication appropriately, are important secondary outcomes of therapy.

General Approach to Treatment

The management of OPC should be individualized for each patient, taking into consideration the underlying immune status, other concurrent mucosal and medical diseases, concomitant medications, and exogenous infectious sources. In HIV-infected patients with inadequately controlled disease, antifungal treatment produces only a transient clinical response, and the relapse rates are higher than in other patient populations. These patients usually require frequent courses of antifungal treatment. Therefore, in patients with HIV disease, treatment with effective HAART is paramount because this would provide the best prophylaxis against recolonization and recurrence of symptoms.34,35,41

Whenever feasible, it is desirable to minimize all predisposing factors, such as administration of corticosteroids, chemotherapeutic agents, and antimicrobials, as well as institute proper oral hygiene and resolve concurrent conditions, such as denture stomatitis. Selection of an appropriate antifungal agent for treatment of candidiasis requires consideration of several factors, including the patient’s drug adherence, adequate saliva for dissolution of solid topical medications, risk of caries from sucrose- or dextrose-containing preparations, potential drug interactions, coexisting medical conditions (e.g., liver disease), location and severity of the infection, and the need for long-term maintenance therapy. Another factor that could affect drug selection is overuse of fluconazole, leading to the emergence of fluconazole-resistant species of C. albicans, and in some cases to all azoles, and other intrinsically more resistant species, such as C. krusei, C. glabrata, and C. tropicalis.

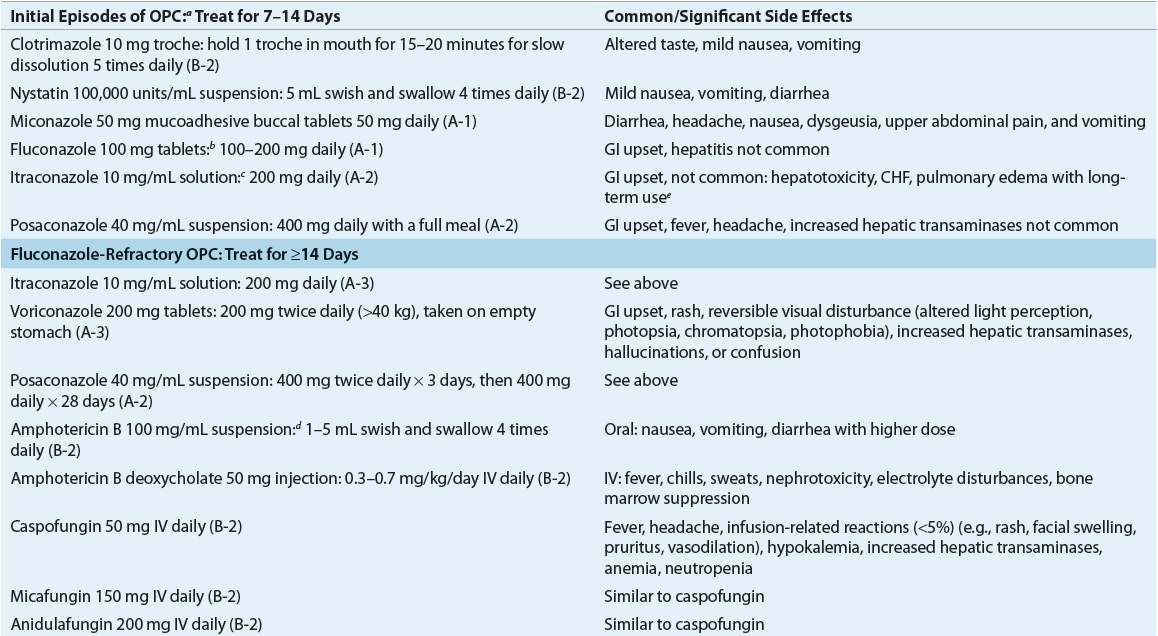

![]() Topical antimycotic therapies should be the first choice for milder forms of infections.41 The efficacy of antimycotic agents for OPC varies in different patient populations. Until the polyene antimycotic agents became available in the 1950s, gentian violet, an aniline dye, was used to treat OPC. Problems with gentian violet include fungal resistance, skin irritation, and especially the unaesthetic staining of the oral mucosa. In resource limited areas gentian violet remains a therapeutic option. A study of different concentrations of gentian violet demonstrated that a 0.00165% solution does not stain the oral mucosa and has potent antifungal activity.42 Topical agents, such as nystatin and clotrimazole, have been the standard of treatment for uncomplicated OPC and generally are effective for treatment in otherwise healthy adults and infants with no underlying immunodeficiencies. Topical agents are available in an assortment of formulations, including oral rinses (suspension), troches, powder, vaginal tablets, creams and most recently as a mucoadhesive tablet37,41,43 (Table 98–6).

Topical antimycotic therapies should be the first choice for milder forms of infections.41 The efficacy of antimycotic agents for OPC varies in different patient populations. Until the polyene antimycotic agents became available in the 1950s, gentian violet, an aniline dye, was used to treat OPC. Problems with gentian violet include fungal resistance, skin irritation, and especially the unaesthetic staining of the oral mucosa. In resource limited areas gentian violet remains a therapeutic option. A study of different concentrations of gentian violet demonstrated that a 0.00165% solution does not stain the oral mucosa and has potent antifungal activity.42 Topical agents, such as nystatin and clotrimazole, have been the standard of treatment for uncomplicated OPC and generally are effective for treatment in otherwise healthy adults and infants with no underlying immunodeficiencies. Topical agents are available in an assortment of formulations, including oral rinses (suspension), troches, powder, vaginal tablets, creams and most recently as a mucoadhesive tablet37,41,43 (Table 98–6).

TABLE 98-6 Therapeutic Options for Mucosal Candidiasis