Christine Youdelis-Flores, MD, R. Jeffrey Goldsmith, MD, DLFA PA, FA SAM, and Richard K. Ries, MD, FA PA, FA SAM

85

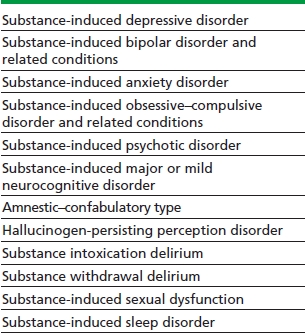

Substance-induced psychiatric disorders are difficult to distinguish from traditional psychiatric illnesses such as depressive, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. The DSM-5, published in 2013, did not change DSM-IV guidelines for diagnoses but added a few new substance-induced mental disorders: substance-induced bipolar disorder and related conditions (which was previously listed in DSM-IV under substance-induced mood disorders), substance-induced obsessive–compulsive disorder and related conditions, and substance-induced major and mild neurocognitive disorder, which include the specifier amnestic- confabulatory type (Table 85-1).

TABLE 85-1. DSM-5 SUBSTANCE/MEDICATION-INDUCED MENTAL DISORDERS

PREVALENCE OF SUBSTANCE-INDUCED PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

Substance-Induced Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Prevalence rates of substance-induced psychiatric disorders vary considerably depending on the populations studied (treatment-seeking subjects vs. epidemiologic surveys). More recent studies using DSM-IV criteria and structured clinical interviews show a wider variety of results depending largely on the study population used. A major epidemiologic study found the prevalence of substance-induced mood and anxiety disorders to be extremely low in the general non–treatment-seeking population. However, the prevalence of those with current independent mood disorders who reported having both independent and substance-induced mood disorders in the prior year was 7.35%. Of those with current independent anxiety disorders, 2.95% reported having both substance-induced and independent anxiety disorders in the prior year. Among depressed people with alcohol use disorders seeking inpatient psychiatric care, around one third to one half are diagnosed with substance-induced depressive disorder.

Stimulant-Induced Depressive and Anxiety Disorders

Cocaine withdrawal is highly associated with depressive symptoms, while intoxication and withdrawal are associated with anxiety symptoms. Methamphetamine users are also reported to have high rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms and suicidal behavior during active use as well as during withdrawal and early abstinence.

Substance-Induced Psychotic Disorders

Psychosis during intoxication is common among those abusing psychotomimetic drugs of abuse, which include cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines and related stimulants, hallucinogens, and dissociative drugs such as phencyclidine (PCP) and ketamine. Regarding the prevalence of substance-induced psychotic disorders (SIPD), Caton et al. evaluated psychotic individuals with substance abuse presenting to a psychiatric emergency department and reported a prevalence of 44% for SIPD, while the other 56% had a primary psychotic disorder (PPD) with concurrent substance use. In a later study by Fraser et al., 56% of first-episode patients had SIPD and 44% were diagnosed with PPD.

An Australian study reported that the prevalence of psychosis among current methamphetamine users not presenting for treatment was 11 times higher than among the general population. Although methamphetamine psychosis in general has a better prognosis than does a PPD, studies conducted in Japan showed that chronic intravenous methamphetamine use is associated with increased rates of prolonged psychosis persisting for several months to over 2 years after abstinence, which closely resembles paranoid schizophrenia.

Substance-Associated Suicidal Behavior

Substance-induced depression can dissipate rapidly, but it is as dangerous as is major depressive disorder in terms of the risk of suicide and self-injurious behavior. When completed suicides are investigated, the rate of comorbidity is high. European autopsy studies of suicide victims report that around 40% had alcohol dependence and that half of them had comorbid depression and 42% had a personality disorder. Studies suggest that alcohol dysregulates mood independent of use patterns, suggesting that some individuals are at risk of severe depression regardless of the chronicity of their alcohol use. Both independent depression and substance-induced depression are associated with suicidal ideation and planning, and aggression is correlated with suicide attempts.

Substance-Induced Bipolar Disorder and Related Conditions

In DSM-5, this mental disorder is listed under the category of Bipolar and Related Disorder rather than Substance-Related Disorders. Substances or medications that are typically associated with this diagnosis include stimulants as well as PCP and steroids. The prevalence of substance-induced mania or hypomania is unknown as there are no epidemiologic studies.

Substance-Induced Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder and Related Conditions

This mental disorder is listed under the DSM-5 chapter on obsessive–compulsive disorder and related conditions. Obsessions, compulsions, hair pulling, skin picking, or other body-focused repetitive behaviors can occur in association with stimulant intoxication. Prevalence is unknown and rare according to DSM-5.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

The differential diagnosis of substance/medication- induced mental disorders includes ruling out traditional mental disorders, which often co-occur with substance use disorders. According to DSM-5, the criteria for all substance/medication-induced mental disorders include the following:

1. The disorder represents a clinically significant symptomatic presentation of a relevant mental disorder, and there is evidence from history, examination, or laboratory finding that the disorder developed during or within 1 month of substance intoxication, withdrawal, or taking a medication.

2. The involved substance/medication is capable of producing the mental disorder, and the disorder is not better explained by an independent mental disorder. Evidence of an independent mental disorder could include:

a. Episodes of the disorder preceding the onset of severe intoxication or withdrawal or exposure to the medication.

b. The full mental disorder persisted for a substantial period of time (at least 1 month) after the cessation of acute withdrawal or severe intoxication or taking the medication. This criterion does not apply to substance-induced neurocognitive disorders or hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, which persist beyond the cessation of acute intoxication or withdrawal.

3. The disorder did not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium, and it must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

DSM-5 notes that the diagnosis of a substance- induced mental disorder should only be made in addition to substance intoxication/withdrawal-induced symptoms if the mental symptoms are prominent and sufficiently severe to warrant clinical attention.

DIAGNOSTIC ISSUES

The clinician should consider the following: Is there a prominent symptom? Is this symptom related to drug, alcohol, or medication use? Is this situation better explained by another DSM diagnosis? Did this situation occur exclusively during a delirium? Is the symptom in excess of the symptoms normally encountered during intoxication or withdrawal? Is the symptom excessively prominent considering the amount of substances used?

Differentiating Between Co-Occurring and Substance-Induced Disorders

Because of denial, the patient may not associate the mental disorder with substance use. The clinician should take a careful history and seek confirmation of the history from collateral informants and medical records. Establishing whether there is a relationship between the use of psychoactive substances and the symptoms is a crucial step. Chronic use of alcohol, sedatives, and opiates can cause depressed mood, as can withdrawal from stimulants and sedatives. Exploring the mental symptoms during periods of sustained abstinence from all substances is critical. In making the diagnosis of substance-induced psychiatric disorder, it is helpful to order a drug screen to confirm the presence of a substance despite the patient’s denial. Such a screen also can clarify the history in some future episode.

It is difficult to differentiate between substance-induced and independent depressive disorders, and the diagnosis may change if the patient is followed over time. Approximately one quarter to one third of people diagnosed with substance-induced depression are found to also have independent major depression after achieving sobriety. Those who have a past history of independent major depression and those who have lower severity of alcohol dependence are more likely to be reclassified as having independent major depression.

Among young people, substance use is common in first-episode psychosis, and the differentiation of SIPD from PPD is challenging and requires a careful psychiatric and substance use history, drug screen, and collateral information from family and friends. As yet, there has been surprisingly little research published on differentiating SIPD from PPD, and an even smaller amount has been published on the epidemiology, treatment, course, and prognosis of SIPD. The differential diagnosis of methamphetamine psychosis and PPD is difficult, and a recent multisite international study has concluded that the severity of psychotic symptoms, including the negative ones, observed in methamphetamine psychotic and schizophrenic patients is similar. The prognosis for SIPD is considered to be good as long as the individual refrains from substance use. The time limit of substance-induced psychotic symptoms that must persist before a PPD should be diagnosed is unclear as yet. Most cases of SIPD are short-lived and resolve within 1 to 14 days with the exception of methamphetamine psychosis since persistent psychotic symptoms after heavy and/or long-term use have been well documented in several studies.

Choosing Levels of Care

The ASAM Criteria describes how to assess treatment intensity for care of a person with an addiction problem. It involves a multidimensional assessment and recommends a broad and flexible continuum of care that is driven by clinical needs and evidence-based treatment outcomes. The multidimensional assessment is broken down into six dimensions: acute intoxication and/or withdrawal potential; biomedical conditions and complications; emotional, behavioral, or cognitive conditions and complications; readiness to change; relapse, continued use, or continued problem potential; and recovery/living environment. Clinical needs are addressed by risk assessments in each of the six dimensions, addressing the severity of the individual’s current risk and level of function, compared to the baseline functioning. Imminent risk requires a treatment plan that addresses this risk until the risk is less intense. The clinical needs of each dimension are addressed in the treatment plan over time and are monitored for changes over time. The ASAM Criteria addresses each of these assessments in greater detail. Treatment planning is a moment-by-moment assessment now, not a program model where everyone gets the same treatment.

TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

For substance-induced depressive disorder, the symptoms should remit over the first month of abstinence. Careful follow-up during this period is very important with outpatient treatment because of the possibility that the diagnosis may be co-occurring major depression. In that case, treatment of the co-occurring mental disorder with medication will be important for successful treatment of the addictive disorder. Disulfiram and anticraving medications such as naltrexone, acamprosate, and injectable naltrexone are helpful when the patient is cooperative, somewhat open to the idea of abstinence from alcohol and willing to engage in some kind of psychosocial follow-up.

For substance-induced anxiety disorders, efforts should be made to rule out other organic causes of anxiety and agitation, such as hyperthyroidism or medication-induced anxiety. A drug toxicology screen should be done, and a phone call to a family member or friend may add confidence to the diagnosis and rule out chronic anxiety and paranoid disorders. Because the patient’s denial may be convincing, it is not sufficient to dismiss substance dependence or a substance-induced disorder based on his history. If the patient’s report is the only information available, the clinician must make a treatment decision, while remaining aware that new information could change the diagnosis and treatment plan. After detoxification is completed, substance-induced anxiety disorders should be managed with nonaddictive alternatives. The use of benzodiazepines in alcoholics after detoxification is achieved is controversial, even in the face of severe anxiety. The anxiolytic properties of benzodiazepines are sustained over time; however, many alcohol- and opiate-dependent folks are susceptible to developing subsequent dependence on sedative–hypnotics, and so the use of antianxiety agents such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other antidepressants or certain anticonvulsants would be a safer strategy. The same problem is encountered with the complaints about insomnia. Avoiding sedatives is important. Use of sedating antidepressants such as trazodone or mirtazapine can be very effective and avoids the abuse potential of other sedative drugs; however, if poor sleeping is caused by sleep apnea, medications may not be helpful.

For SIPD, a medical workup to rule out organic disorders and to diagnose and treat medical disorders associated with the substance use is important. A screening battery is recommended, because nutritional deficiencies often are found and, not infrequently, viral hepatitis (B or C). Unsafe sexual practices and needle sharing should warrant testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. SIPD prognosis depends on motivation and success in addiction treatment and is considered to be good as long as the individual refrains from substance use. Non–evidence-based treatment recommendations for SIPD include benzodiazepines to manage acute agitation during intoxication followed by atypical antipsychotic administration should the psychosis be severe or not resolve within 1 to 2 weeks after cessation of drug use. It is essential that the patient understands the role the substance has played in decompensation and the likelihood of worsening and prolonged psychosis should relapse occur. If psychosis persists despite abstinence, a PPD must be considered.

KEY POINTS

1. Most patients with substance-induced mental disorders can be diverted away from traditional psychiatric inpatient treatment, either to dual diagnosis units or to inpatient or outpatient addiction treatment programs in which adequate assessment and appropriate treatment are available.

2. Dual diagnosis clinics and residential units that specialize in substance-dependent patients who have a comorbid psychiatric illness play an important role when there is diagnostic confusion or when the patient does not respond to routine psychiatric treatment.

3. Confusion about the diagnosis can delay interventions; therefore, achieving clarification through a comprehensive evaluation is the first order of business, after safety is addressed.

4. Although abstinence is a critical factor in recovery from a substance-induced mental disorder, it is not always the only factor.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. Prolonged substance-induced psychosis is common with chronic use of:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree