Bacteria are the most common contaminants of IV fluids. They are large enough to be stopped by most filters used in admixture preparation or fluid administration to the patient. When bacteria are present in large enough quantities (about 10 million to 100 million organisms per milliliter), the CSP will look cloudy or turbid.

Viruses are the smallest microbe. They are so small that they can pass through pharmaceutical filters. Viruses require a living host to grow, so they do not grow in IV fluids even though they may cause infection in the patient when the fluid is administered. Viruses do not cause the solution to appear turbid, and they cannot be detected by commonly used methods of checking IV fluids for contamination. Thus, the patient’s only defense against viruses is that they are not introduced into the fluid to begin with.

To avoid introducing microbial organisms into CSPs, pharmacists and technicians use aseptic technique in handling CSPs. Aseptic technique involves taking several precautions to prevent introduction of microbes into the products, including initial cleaning of the area used for manipulation of the products, creation of a sterile area and minimization of traffic in that area, gowning and gloving of the people working in the area, and quality controls to make sure that the procedures are in fact preventing contamination of the admixtures being produced. Before we look at what those procedures are, let’s look at the many types of CSPs that are produced in pharmacies.

Injectable Products

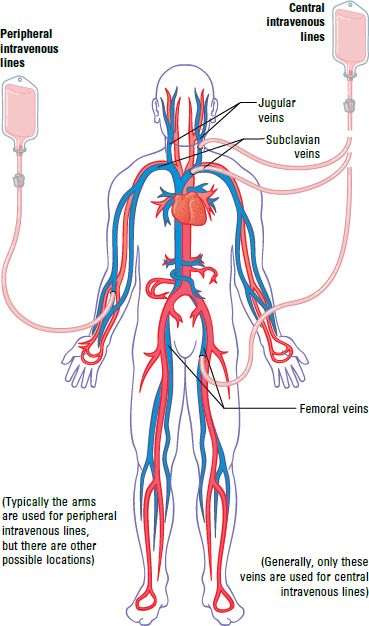

Because many CSPs are placed into patients’ veins, they are often referred to generally as IV fluids (Figure 10-2). For IV administration, the amount of fluid that is infused can vary considerably, but it is usually at least 50 mL to 100 mL and can range to up to several liters of fluid per day. Other types of CSPs can be infused into arteries, administered into the fluid that surrounds the brain and spine, placed into the peritoneal cavity that surrounds the gastrointestinal organs of the gut, or placed into the eyes or joints of the body. CSPs are also used as baths for live organs and tissues after they are harvested from donors but before they are placed into recipients.

Parenteral Solutions

If the amount of IV fluid is less than 250 mL, it is considered a small-volume parenteral (SVP) solution. The main use of SVPs is for administering IV drugs to patients. For instance, a physician might order cefazolin 1 g IV every 8 hours for a patient with an infection. The pharmacy would prepare this amount of drug in 50 mL to 100 mL of a small-volume product, usually either 5% dextrose (a sugar solution) or 0.9% sodium chloride (a salt solution). These solutions would then be infused directly into the patient’s veins.

SVPs are increasingly provided by manufacturers in a ready-to-infuse form. Some of these products are premixed solutions that are stored frozen until ready for use, while others keep the drug separate from the fluids until the time of dispensing or administration. Some newer products allow the drug and solution to be mixed in a closed system. This is advantageous because the manipulation can safely occur in any location, even in the patient’s home if needed. Ask someone in your pharmacy to show you the kinds of SVPs currently in use.

When larger amounts of IV fluids are required, the product is called a large-volume parenteral (LVP) solution. These are usually given to patients continuously, as in an order for 5% dextrose injection 125 mL/hr. In this case, the solution would keep running into the patient’s veins during all hours of the day and night. The patient would receive 3 L/day of 5% dextrose injection (125 mL/hr × 24 hr), a common amount of IV fluid. When a patient has a line running continuously, the small-volume products are piggybacked onto that line, thereby decreasing the number of times a patient has to endure the discomfort of a venipuncture.

In addition to different sizes, IV fluids may be packaged in several different types of glass bottles, plastic bags, or plastic semirigid bottles. Generally within one hospital, health system, or community pharmacy, only one company’s products are used. You should become familiar with those used in your work setting, including the various sizes and container types.

Nutritional Solutions

In addition to SVPs used for drug delivery and LVPs used for volume replacement, pharmacies commonly produce specialized solutions. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is an important type of specialized solution that provides nutrition without the use of the gastrointestinal tract (hence the “parenteral,” which means “other than enteral”). TPNs are used in clinical situations where patients cannot take any food or products by mouth, such as when surgery has been performed on the gastrointestinal tract and it needs to rest so that it can heal.

TPN solutions have high concentrations of glucose (up to 35%), amino acids, and sometimes fats. These solutions are so strong—or concentrated—that they would cause the patient problems if they were infused into a small vein. For this reason, most TPN solutions are administered through tubes inserted into a vein just before it reaches the heart (called central lines). However, some less concentrated TPN solutions are infused into veins in the arms (peripheral lines). Peripheral lines are used in children, for adult patients who need only a few days of TPN, or in other specific clinical situations.

Anytime that the needle of an IV administration set is inserted into a patient, there is an increased risk for infection because the skin—the body’s first line of defense—is broken. This is true for peripheral lines, but it is even more critical for central lines because they are used for long time periods (weeks or months).

When TPN solutions are made in the pharmacy, the pharmacist or technician mixes concentrated glucose and amino acids to create the proper final amounts. Various electrolytes are added to the TPN solution, including sodium, potassium, acetate, chloride, magnesium, and calcium. Because calcium can form insoluble salts with some ingredients (such as phosphate), it must be added in a specific manner to prevent problems. Smaller amounts of vitamins, trace elements (such as chromium, copper, zinc, iodine, and manganese), and other ingredients are sometimes added according to the physician’s instructions. Adult patients generally need about 2 L to 3 L/day of TPN solutions.

To assist in the preparation of TPN solutions, many pharmacies have a machine that can be programmed to mix the proper amounts of glucose, amino acids, and other solutions. These TPN compounding systems are computer-based machines that assist in calculations and help to keep the final products free of microbial contaminants. Some compounding machines can also add electrolytes, vitamins, and other ingredients based on your instructions. You need to keep two factors in mind when using a compounding system:

- The system must be properly calibrated—or adjusted—before you begin, and the proper solutions must be connected to the correct tubing as it goes through the compounding machine.

- Any error you make in entering the ingredients will result in the wrong product. These solutions are very concentrated, and errors can easily cause clinical problems in patients. Be very careful when entering the amounts of the ingredients. To help prevent problems, many pharmacies require that two people check all TPN orders, calculations, and entries. Even if your pharmacy does not require this check, it is a good idea to ask a pharmacist or another knowledgeable technician to check your work when making TPN solutions.

If TPN is the only nutritional source for more than a couple of weeks, the patient will also need a source of fats. These are provided using commercially available emulsified fat products. These fat products are sometimes administered separately because they can be administered via a peripheral line, or they can be mixed with the glucose–TPN solutions in a 3-in-1 admixture.

Another specialized nutritional product is enteral nutrition. These are liquid emulsions (similar in appearance to a milk shake) that are given through a tube inserted through the mouth or nose into the patient’s stomach or small intestine. If at all possible, enteral nutrition solutions are used rather than TPN because they keep the patient’s gastrointestinal tract active and avoid the need for an IV line going into a central vein. Some pharmacies handle enteral nutrition products, but they are also provided by dietitians, or in some institutions, the dietary department.

Making Sterile Products in the Pharmacy

Standards for compounding sterile preparations are defined by the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) in its General Chapter <797>, Pharmaceutical Compounding—Sterile Preparations. This document, which was originally published in 2004 and revised in 2008, has the force of law because USP is recognized as a standards setting organization in federal statutes and regulations.1–2 It is also endorsed by The Joint Commission and incorporated into the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy’s Model State Pharmacy Act and Rules. USP Chapter <797> is an essential regulatory and guidance document for any pharmacy that is compounding sterile products.

Sterile Compounding Standards

USP Chapter <797> provides practice and quality standards designed to prevent patient harm, including death, that could result from one of the following:3

- Microbial contamination

- Excessive bacterial endotoxins

- Variability in the intended strength of correct ingredients

- Unintended physical and chemical contaminants

- Ingredients of inappropriate quality

Excessive bacterial endotoxins can end up in CSPs when bacteria have been introduced and then burst—or lyse—because of the differences between the fluids and the organism’s preferred environment. Although the bacteria are dead, pieces of their cell walls and membranes and cellular structures remain in solution, and these can cause fever and other types of reactions when infused into patients. For this reason, USP specifies tests for endotoxins—which are also known as pyrogens—and you may hear pharmacists talking about these.

To increase the likelihood that patients receive unadulterated CSPs containing the right ingredients and fluids, USP Chapter <797> spells out requirements for sterile compounding policies and procedures; personnel training and evaluation; environmental quality and control; equipment used in CSP production; procedures for compounding immediate-use CSPs; processes for compounding with single-dose and multiple-dose containers; verification of automated procedures such as the TPN compounding system described in the previous section; checks of finished products, storage and beyond-use dating, quality control, packaging and transport/shipping of CSPs; patient or caregiver training; patient monitoring and adverse event reporting; and quality assurance programs. While discussion of all of these aspects is beyond the scope of this chapter, some basic aspects are described here.

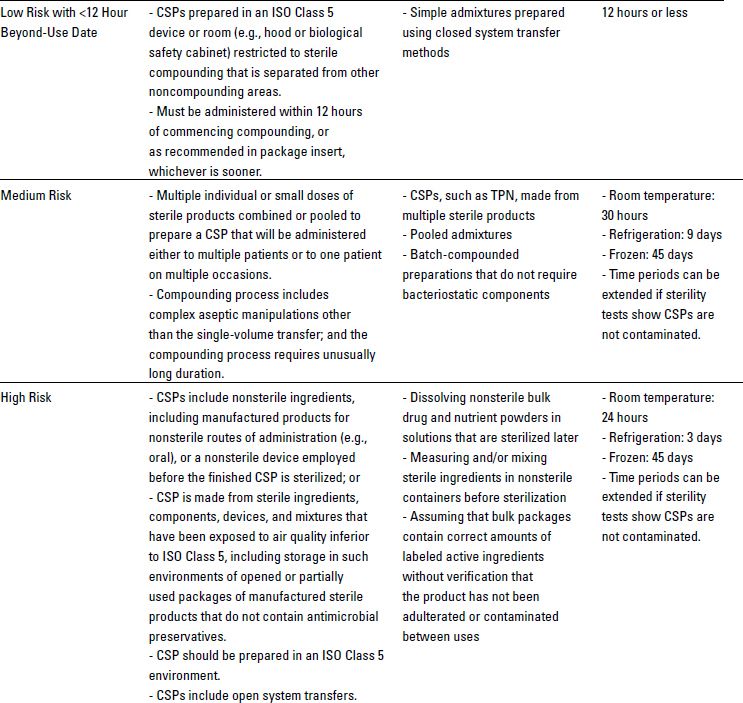

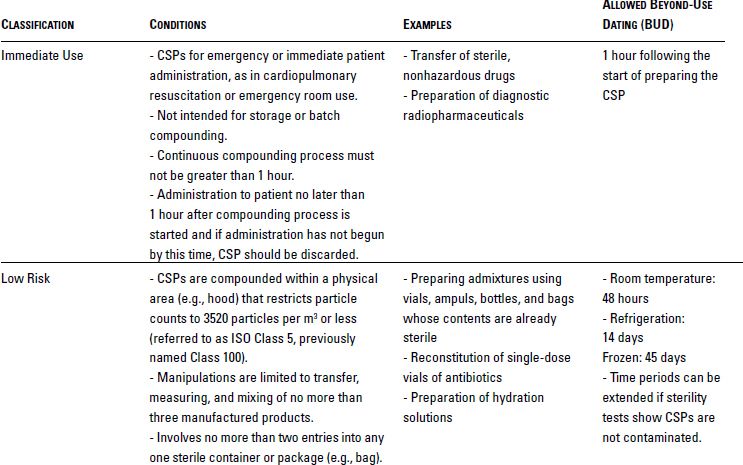

USP Chapter <797> defines the microbial contamination risk levels of products and processes for CSPs that are prepared by personnel in the pharmacy, nursing station, or physician office. As shown in Table 10-1, USP defines these risk levels based on the types of products being used, the complexity of manipulations, and the quality of the environment in which compounding is conducted.

Physical Facilities for Sterile Compounding

The physical environment set forth in USP Chapter <797> can be as simple as a laminar airflow cabinet or biological safety cabinet or as complex as a cleanroom, buffer zone, and anteroom. Laminar airflow hoods blow the air across the work surface in an even—or laminar—manner. Figure 10-3 illustrates aseptic technique in a horizontal laminar airflow hood. The vertical-flow biological safety cabinet is discussed below in the section Special Considerations: Hazardous Drugs.

Sources: United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary. Pharmaceutical compounding—sterile preparations. Rockville, Md.: United States Pharmacopeial Convention; 2008, and American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. The ASHP discussion guide on USP chapter <797>. Available at: http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Compounding/Policies-Best-Practices-and-Guidelines.aspx.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree