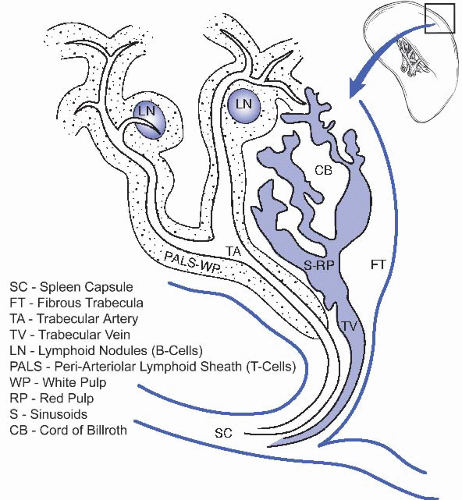

I. NORMAL GROSS AND MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY. The spleen is the largest lymphatic organ. In a normal adult, it weighs 50 to 250 g. Anatomically, the spleen is divided into white and red pulp, separated by an ill-defined interface known as the marginal zone (e-Fig. 45.1A).* For a schematic of splenic architecture, see Figure 45.1.

A. White pulp. The white pulp consists of periarteriolar lymphoid sheets (PALS), which contains lymphoid follicles. T lymphocytes are predominately located in periarteriolar lymphoid nodules and B lymphocytes are predominately located in the lymphoid follicles. The latter may contain germinal centers that become visible to the naked eye when enlarged, forming splenic nodules (malpighian corpuscles). In routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, the white pulp appears basophilic due to the dense heterochromatin in lymphocyte nuclei (e-Fig. 45.1B).

B. Red pulp. The red pulp has a red appearance in fresh specimens and in histologic sections because it contains a large number of red blood cells (e-Fig. 45.1B). It consists of splenic sinuses separated by splenic cords (the cords of Billroth), which are composed of a loose network of reticular cells and fibers with a large number of erythrocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and granulocytes. Special endothelial cells that express both endothelial and histiocytic markers (known as Littoral cells) line the sinuses. The sinusoidal lining epithelium is discontinuous, allowing for transport of blood cells between the splenic cords and sinuses.

II. GROSS EXAMINATION AND TISSUE SAMPLING

A. Biopsy and fine needle aspiration cytology. These procedures are rarely attempted because of the risk of hemorrhage and the likelihood of undersampling. However, some studies suggest increased chances of a definitive diagnosis when fine needle biopsy is combined with flow cytometry, with an overall accuracy of 91% and a major complication rate of <1% (Am J Hematol. 2001;67:93).

B. Splenectomy. Trauma, staging procedures, and surgical convenience account for >50% of all splenectomies. Therapeutic splenectomy for known diagnoses (idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura [ITP], chronic myeloproliferative disorders, lymphomas, etc.) accounts for most of the remaining cases (Cancer. 2001;91:2001). Unexpected pathology is rarely found in splenectomy specimens, but significant splenomegaly (weight>300 g) or localizing lesions warrant careful prosection and ancillary studies.

C. Processing. The spleen is weighed, and its outer dimensions are recorded. Hilar fatty tissue is removed and processed for lymph nodes. The capsule should be described, noting texture and intactness. The spleen should be thinly sliced (every 2 to 3 mm); lesional distribution should be noted, followed by a description of the uninvolved spleen. Sections of any lesions (preferably following overnight formalin fixation of thin slices) and two representative sections of uninvolved spleen should be submitted for microscopic examination.

If clinically indicated, fresh lesional tissue in 1 mm pieces should be placed in RPMI medium and directed immediately to the flow cytometry lab with instructions regarding the appropriate protocol. Cytogenetic studies may be

useful, especially for diagnosis of hematologic malignancies; using sterile technique, lesional material should be procured immediately after removal of the spleen in the operating room and directed to the cytogenetics lab. Samples can also be frozen, or fixed for electron microscopy. Freezing preserves many of the antigens for immunohistochemical evaluation in hematopoietic malignancies and enhances nucleic acid recovery for DNA- and RNA-based molecular diagnostic techniques (although most diagnostic molecular tests can be reliably performed on formalin fixed, paraffin embedded material).

III. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

A. Splenomegaly. Often the spleen becomes enlarged due to infectious causes or congestive states. Red pulp congestion is frequently observed and is the most common finding in such cases (Table 45.1).

B. Hypersplenism. Hypersplenism refers to destruction of one or more blood cell lines by the spleen (Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:317). It is the most important indication for elective splenectomy. Diagnostic criteria for hypersplenism include cytopenia of one or more blood cell lines, bone marrow

hyperplasia, splenomegaly, and correction of cytopenia(s) following splenectomy. Of the many possible etiologies (see Table 45.2), congenital disorders such as hereditary spherocytosis (e-Fig. 45.2), infiltrative disorders such as leukemias and lymphomas (e-Fig. 45.3), and autoimmune disorders are the most common.

TABLE 45.1 Conditions Associated with Splenomegaly

Infection

Infectious endocarditis

Infectious mononucleosis

Tuberculosis

Histoplasmosis

Syphilis

Parasitic infections (e.g., malaria)

Cytomegalovirus

Congestive states

Cirrhosis

Splenic vein thrombosis

Heart failure

Hematologic malignancy

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma

Myeloproliferative disorders

Multiple myeloma

Immune-related conditions

Rheumatoid arthritis

Systemic lupus erythematous

Storage disorders (e.g., Gaucher disease)

Adapted from Pathologic Basis of Disease, 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 2009.

C. Hyposplenism. Hyposplenism refers to any deficiency or absence of a functioning spleen and is usually due to splenectomy. Splenic function is usually assessed by radiologic imaging or morphologic techniques. Peripheral blood smear examination may also be informative; findings suggesting hyposplenism can

occur in any blood cell line, including erythrocytes (Howell-Jolly bodies [e-Fig. 45.4], poikilocytosis with target cells, acanthocytes, and nucleated red blood cells), platelets (thrombocytosis), and white blood cells (e.g., lymphocytosis, monocytosis, and eosinophilia). Other causes of hyposplenism include congenital hypoplasia (e.g., Fanconi anemia and sickle cell disease; e-Fig. 45.5), infiltrative disorders, old age, and many others (see Table 45.3).

TABLE 45.2 Disorders Associated with Hypersplenism

Abnormal sequestration of intrinsically defective blood cells in a normal spleen

Congenital disorders of erythrocytes (hereditary spherocytosis, elliptocytosis; hemoglobinopathies, e.g., sickle cell disease, unstable hemoglobins)

Acquired disorders of erythrocytes (autoimmune hemolytic anemias, malaria, babesiosis)

Autoimmune thrombocytopenia and/or neutropenia

Abnormal spleen causing sequestration of normal blood cells

Disorders of the monocyte/macrophage system (chronic congestion, storage diseases, parasitic infections, LCH, etc.)

Malignant Infiltrative disorders (leukemias, lymphomas, plasma cell dyscrasias, metastatic carcinoma)

Extramedullary hematopoiesis (severe hemolytic states, chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis)

Chronic infections, for example, tuberculosis, brucellosis

Vascular/stromal abnormalities (vascular tumors, peliosis, splenic cysts, hamartomas)

Miscellaneous conditions

Hyperthyroidism

Hypogammaglobulinemia

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

TABLE 45.3 Disorders Associated with Hyposplenism

Congenital

Asplenia

Hypoplasia

Immunodeficiency disorders

Acquired

Splenectomy

Acquired atrophy and/or infarction

Sickle cell disease

Vascular disorders (vasculitides, thromboembolic conditions)

Essential thrombocythemia

Malabsorption syndromes

Autoimmune diseases

Irradiation

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Chronic alcoholism

Hypopituitarism

Functional asplenia with normal-sized or enlarged spleen

Infiltration by leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, mastocytosis

Early (splenomegalic) sickle cell disease

Amyloidosis

Sarcoidosis

Benign and malignant vascular tumors

Malabsorption syndromes

Depressed immune function

AIDS

Status post

Irradiation

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Immunosuppressive agents, including corticosteroids

Endocrine disorders

Hypothyroidism

Hypopituitarism

Diabetes mellitus

Chronic alcoholism

D. Accessory spleen. Alternatively termed “spleniculi,” these are most commonly located in the splenic hilum, tail of the pancreas, and the gastrohepatic ligament (N Engl J Med. 1981;304:11). They are found in up to one-third of autopsy cases and share the same histologic and pathologic features as native spleen (see e-Fig. 45.6). Accessory spleens are clinically significant in patients requiring splenectomy for hypersplenism.

E. Splenosis. Splenosis refers to splenic implants or regrowth of splenic tissue after trauma or surgical splenectomy. When associated with trauma, the most common location is in the abdominal cavity, but splenosis has been reported at virtually all anatomic sites, including the brain (Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:894).

Usually benign incidental findings, their clinical importance lies in their potential to mimic neoplastic and nonneoplastic splenic lesions.

IV. REACTIVE SPLENIC DISORDERS. These can be divided into diffuse and localized processes. Diffuse disease entities include reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (e-Fig. 45.7A), follicular hyperplasia, and disorders such as Castleman disease (see Chap. 43). Localized disease includes granulomatous disorders and infectious processes similar to those in other locations (see Chap. 43).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Spleen

Spleen

Mohammad O. Hussaini

Anjum Hassan