The main question posed by clinicians whenever a spleen is removed for “idiopathic splenomegaly” is whether an underlying lymphoma is present (

39). In fact, lymphomas restricted to the spleen are uncommon. Most patients who have lymphoma that is first discovered in the spleen have the simultaneous involvement of splenic hilar or abdominal lymph nodes (

40). In one series, only 17 of 500 splenectomy specimens (3.4%) with

malignant lymphoma were identified as primary lymphoma of the spleen (

41). Similarly, only 65 of 1280 (5%) sequential splenectomy specimens were found to contain primary lymphoma (

42). Alternatively, occult lymphoma was discovered in 7 of 18 (39%) patients who underwent splenectomy for idiopathic splenomegaly, most of whom had clinical hypersplenism (

43), and in a study from Japan that comprised 184 splenic specimens with suspected lymphoma, 115 (62.5%) were determined to be lymphoid neoplasms (

44); however, with the exception of large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL), the other newly diagnosed lymphoma cases in that series were discovered in patients with advanced stage disease. LBCL is the most common type of primary splenic lymphoma encountered, with splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL) being second in frequency (

42,

44). Other series also have documented SMZL as the most frequent form of primary splenic low-grade lymphoma (

45,

46).

Among patients with known lymphomas, including Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), data from staging laparotomy studies indicate that the spleen is affected in approximately 40% of patients (

47); for patients with FL, the prevalence of splenic involvement increases to 56% (

48). Although lymphomas develop mainly in the white pulp, the distributional pattern of the various histologic types is diverse yet frequently pathognomonic (

49). In the case of many lymphomas, the red pulp is infiltrated secondarily; for some lymphomas, including those composed of large cells, the red pulp is the dominant site of involvement (

Table 18.2).

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma

The histologic and immunophenotypic features of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are identical to those described for small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), so both disorders are categorized as a single entity in the WHO classification (

14). Prior to the recognition of SMZL, historically, SLL was the most common type found in patients with primary lymphoma in the spleen (

40). Because the majority of patients with this type of lymphoma have stage IV disease, splenic involvement is common (

14,

50). In cases of CLL/SLL, splenectomy usually is performed because of hypersplenism or autoimmune phenomena and progressive or refractory disease in patients with splenomegaly (

51).

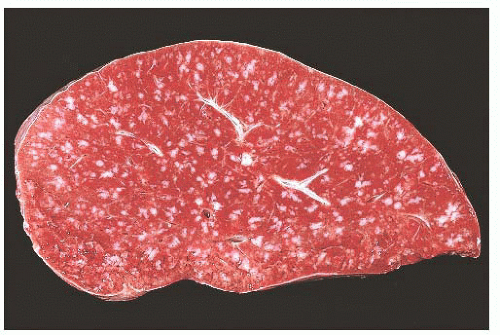

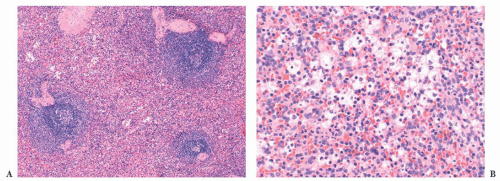

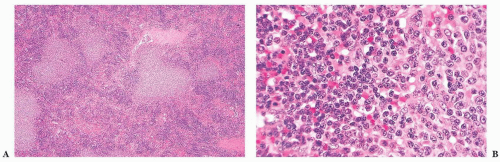

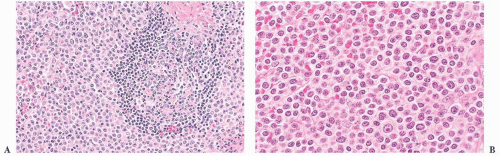

The diagnosis generally is not difficult to determine. In CLL/SLL, the splenic white pulp areas, including the marginal zones and T-cell regions, are randomly expanded and effaced by a proliferation of small, round lymphocytes (

49,

52). On the cut surface, the white pulp is prominent, and the nodules are asymmetric. Frequently, adjacent expanded white pulp nodules coalesce, and simultaneous diffuse invasion of the red pulp cords and sinuses generally is observed (

Fig. 18.7); infiltration of the trabeculae and the subendothelium also occurs. In some cases, the involvement of the red pulp may be so widespread that the white pulp component is obscured. These unusual cases can be difficult to distinguish from hairy cell leukemia (HCL), but immunophenotypic studies, specifically the finding of CD5 and CD23 expression in paraffin sections in CLL/SLL, coupled with a lack of markers associated with HCL—such as tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), DBA.44, cyclin D1, T-bet, CD123, annexin A1, and/or CD103—aid in the diagnosis (

53,

54 and

55).

Other circumstances in which the diagnosis of CLL or SLL of the spleen may be challenging are encountered. One such situation may be the consequence of epithelioid granulomas developing in both splenic white and red pulp. If the granulomas are sufficiently extensive, they may mask the underlying lymphoma (

56). Epithelioid granulomas may also manifest in other splenic small B-cell lymphomas, including SMZL, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), and lymphomas that are not otherwise classifiable (

52,

57). A second source of diagnostic difficulty is encountered in patients whose spleens are of normal weight or minimally enlarged weighing less than 300 to 400 g and removed

because of ITP, hypersplenism, or at exploratory laparotomy. Under these conditions, subtle white pulp expansion may be present as a result of a proliferation of small, round lymphocytes (

45). Because the small lymphocytes are indistinguishable from normal-appearing reactive lymphocytes, cytologic evaluation is not helpful in this situation. A diagnosis of malignancy may be suspected because of fusion of adjacent white pulp segments with or without secondary spread to the splenic red pulp, and if fresh splenic tissue is available, immunophenotypic analysis, usually by flow cytometry, is required to determine monoclonality and whether CD5 and CD23 are coexpressed (

53). If only fixed tissue is accessible, a B-cell immunophenotype with CD5 and CD23 coexpression by immunoperoxidase will facilitate a diagnosis of occult CLL/SLL and separate such cases from reactive lymphoid hyperplasia or another lymphoma. Lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1) also may prove valuable as a marker of CLL/SLL in contrast to other lymphomas that are composed of small lymphocytes (

58).

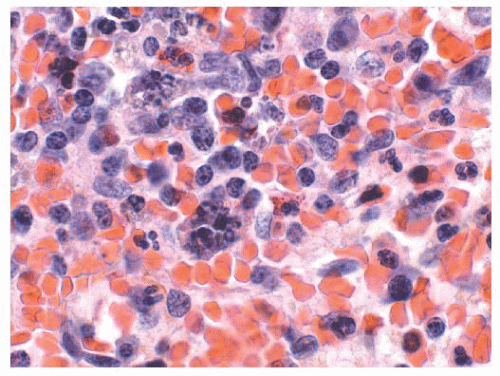

A third problem in establishing a diagnosis of CLL/SLL is seen in cases in which the formation of proliferation centers in the white pulp occurs (

52,

59). The admixture of larger lymphocytes, specifically prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts in the proliferation centers, frequently leads to the misdiagnosis of follicular grade 2 lymphoma or even LBCL (

Fig. 18.8); unlike what is found in these other lymphomas, the admixed small lymphocytes in CLL/SLL are round and they are devoid of atypia. The large lymphocytes found in CLL/SLL of the spleen are identical to those reported in their nodal counterparts. If the number of large cells is relatively small, they likely have no bearing on prognosis; however, the identification of focal aggregates of large cells is an uncertain prognostic factor (

14,

60). On occasion, we have seen spleens in which the number of large cells was so great that it indicated transformation of CLL/SLL to LBCL analogous to Richter syndrome. In splenic Richter syndrome, often a strict compartmentalization of the residual CLL/SLL and the LBCL is present; the small lymphocytes of CLL/SLL are confined to the red pulp, whereas LBCL replaces the white pulp (

Fig. 18.9) (

45).

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma

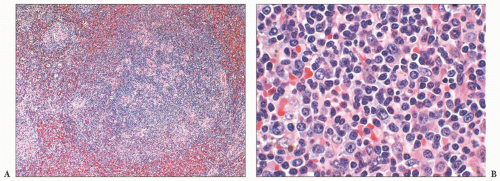

LPL and its clinical counterpart, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, is composed of a variable mixture of small lymphocytes, plasmacytoid lymphocytes, and plasma cells, including cells with Dutcher bodies, generally without CD5 and CD23 expression (

14,

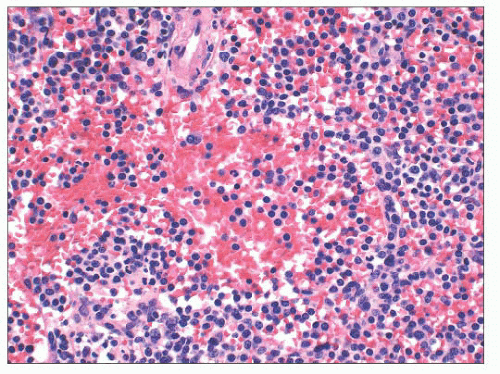

61). In the spleen, the distributional features are histologically indistinguishable from CLL/SLL. The white pulp is irregularly enlarged as a result of lymphoma. The T-cell areas are often infiltrated, epithelioid histiocytes may be prominent, and nodules may form in the red pulp (

Fig. 18.10) (

45,

49,

62). In some cases, the red pulp is diffusely infiltrated with loss of the white pulp and the characteristic nodular pattern of most splenic lymphomas (

45,

62,

63). The absence of proliferation centers and the usual lack of CD5 and CD23 expression serves to distinguish LPL from cases of CLL/SLL with plasmacytoid cells; moreover, the cases of LPL that coexpress CD5 and CD23 usually exhibit partial expression of these antigens in contrast to CLL/SLL (

61). LPL is more difficult to distinguish from SMZL,

specifically from those cases of SMZL that exhibit plasmacytoid features, because of overlapping immunophenotypic as well as morphologic features (

64,

65). Both entities are composed of small lymphocytes, lymphoplasmacytoid cells, and plasma cells with similar distributional features in the spleen. Whereas the presence of a pale corona surrounding residual reactive or colonized germinal centers and the identification of marginal zone lymphocytes commonly distinguishes SMZL from LPL, the differential diagnosis can be onerous. Reportedly, one measure of distinction is that the plasma cells in LPL abnormally coexpress CD138 and PAX5 and the median percentage of this coexpression is significantly higher than found in marginal zone lymphoma (

66). For certain cases, however, an absolute distinction between LPL and SMZL may not be possible, resulting in a diagnosis of “small B-cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation” (

14,

61).

Primary plasmacytomas of the spleen are rare and splenic involvement by systemic plasma cell myeloma also is uncommon, although splenomegaly is found in the context of plasma cell leukemia (

59,

67). Primary splenic plasmacytomas cause massive splenomegaly, and spontaneous rupture may develop (

59). Tumor nodules form owing to expanded white pulp segments and nodular aggregates of plasma cells in the red pulp, but, as with LPL, the red pulp may be diffusely infiltrated. The plasma cells range from mature forms to plasmablasts and both binucleated and multinucleated plasma cells are encountered (

67). Cytoplasmic monotypic immunoglobulin expression is readily detectable. Distinguishing plasmacytoma dominated by plasmablasts from plasmablastic lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation is problematic because they share the morphologic and immunophenotypic features of a neoplasm of terminal B-cell differentiation, so that the clinical characteristics remain the only reliable mechanism for accurate classification (

68).

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) typically is a clinically aggressive lymphoma of small lymphocytes that mainly arises from naïve, unmutated, pregerminal center cells localized in primary follicles or the lymphocyte corona or mantle zone surrounding secondary follicles; a subset exhibits somatic hypermutation and arises from antigen-encountered B cells (

14,

69,

70 and

71). MCL bears some histologic and immunophenotypic similarities to CLL/SLL, including coexpression of CD5 and CD43, but MCL does not have proliferation centers, and despite some variation, it generally fails to react for CD23 (

69,

70,

71 and

72). Curiously, CD23 expression in MCL is associated with a superior clinical course (

72). Of most significance, almost all cases of MCL contain the t(11;14) chromosomal translocation with virtual universal overexpression of cyclin D1 protein (

69,

70 and

71). MCL usually also expresses SOX11 and this neuronal transcription factor identifies rare cyclin D1-negative cases, including the blastoid variant (

73). SOX11-negative MCL patients are few, but such patients tend to have leukemic disease without lymphadenopathy but with frequent splenomegaly, lack genomic complexity, and display an indolent clinical course as compared to SOX11-positive patients (

74). The inferior survival of the SOX11-positive MCL patients likely is related to the demonstration that SOX11 contributes to tumor development by blocking the terminal B-cell differentiation program in MCL (

75).

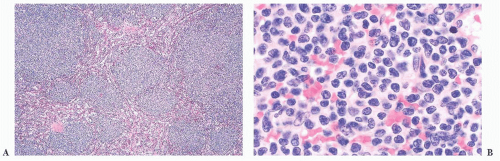

Many patients with MCL have splenomegaly and advancedstage disease on initial examination (

70). In one series, 42% of patients with primary small B-cell lymphoma in the spleen were diagnosed as having the mantle cell type (

46). As noted earlier, patients with MCL who present with splenomegaly and without lymphadenopathy generally manifest a leukemic phase, whereas those with the blastoid variant may develop spontaneous splenic rupture (

74,

76). In some patients with the splenomegalic form of MCL, the peripheral blood and spleen contain nucleolated cells to mimic prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL) (

77); unlike PLL, the MCL cases harbor the t(11;14) translocation and express cyclin D1. In the prototypic spleen of patients with MCL, the white pulp is irregularly expanded by a proliferation of small lymphocytes with dense chromatin, indistinct nucleoli, and variable nuclear membrane irregularities (

Fig. 18.11) (

52). The expanded white pulp may result

in confluent tumor nodules or enlarged lymphocytic coronas that surround any residual secondary germinal centers and frequently obliterate the marginal zones. The red pulp cords and sinuses are often infiltrated and the lymphoma frequently forms small nodules in the red pulp (

45,

46,

52). In the splenic cases of MCL that simulate PLL, the lymphomatous cell population is more heterogeneous and includes intermediate-sized cells with coarse, clumped chromatin and single central, small, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, in addition to the more typical lymphocytes of MCL (

77). In some case of splenic MCL, marginal zonelike differentiation—in which cells with more abundant pale-staining cytoplasm are evident—may occur, suggesting SMZL (

78); this diagnostic issue is particularly relevant in cases with associated residual germinal centers. The relative monomorphous cytologic appearance, together with cyclin D1 reactivity, should establish the diagnosis of MCL.

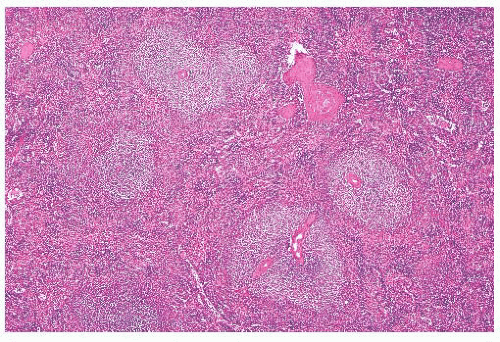

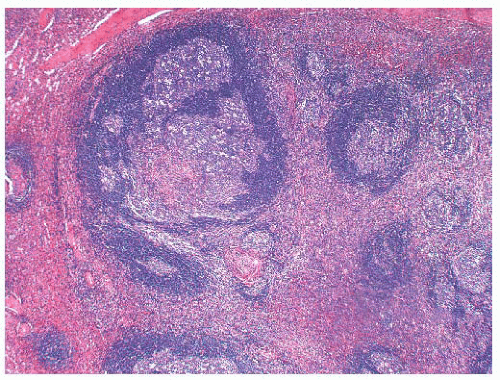

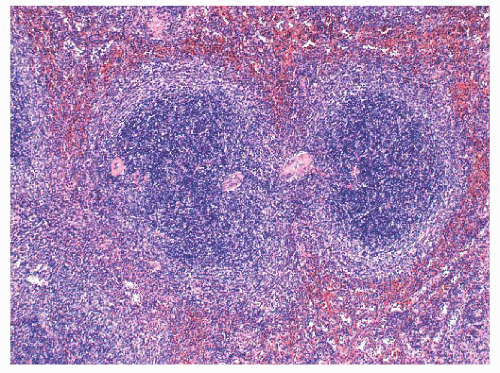

The presence of residual germinal centers in the spleen in cases with the uncommon mantle zone pattern of MCL also may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of reactive follicular hyperplasia. In MCL, however, adjacent white pulp segments coalesce (

Fig. 18.12); this observation, when coupled with frequent secondary involvement of the red pulp and nuclear atypia in the proliferating lymphocytes surrounding the germinal centers, serves to distinguish MCL in the spleen from reactive follicular hyperplasia on histologic examination. Immunologic studies demonstrating monoclonality, aberrant CD5 reactivity in B cells, and cyclin D1 expression confirm the diagnosis.

Splenic Marginal Zone Lymphoma

SMZL is a low-grade lymphoma that probably encompasses many primary splenic lymphomas that previously were regarded as CLL/SLL and LPL, rendering SMZL currently the most common primary low-grade lymphoma of the spleen (

42,

44,

45 and

46,

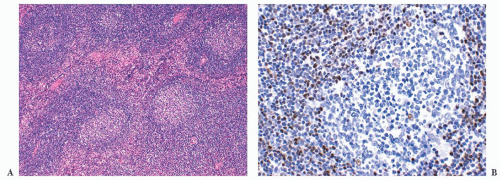

79). SMZL exhibits histologic heterogeneity, but this lymphoma usually exhibits a marginal zone (monophasic) or a biphasic

pattern (

80,

81). The marginal zone or monophasic pattern is characterized by expansion of the marginal zone of the splenic white pulp due to a proliferation a marginal zone lymphocytes, together with varying numbers of larger blast-like cells and plasma cells (

46,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83 and

84). Marginal zone lymphocytes are small to medium-sized cells with ovoid to reniform-shaped nuclei and a characteristically abundant pale-staining cytoplasm that differentiates them from adjacent mantle zone lymphocytes. Splenic marginal zone lymphocytes resemble monocytoid B cells, and cases of disseminated nodal MZL and extranodal MZL of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) have in fact been reported in the spleen, where they involve the splenic marginal zone and are indistinguishable from primary SMZL (

85,

86).

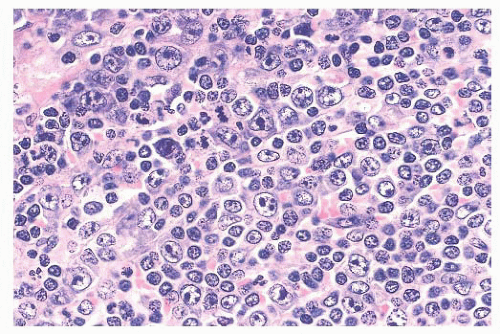

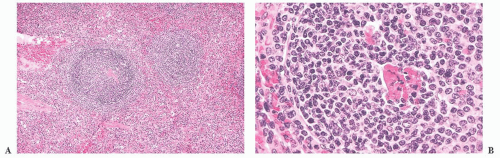

In SMZL, the marginal zones are expanded and the neoplastic marginal zone lymphocytes surround, encroach upon, and frequently invade attenuated rims of mantle zone lymphocytes and secondary germinal centers, if these are present (

Fig. 18.13). This marginal zone (monophasic) pattern may be observed in both massively enlarged spleens and spleens of normal weight in the presumed early phase of the lymphoma (

87). In the latter case, replacement of the T cells in the periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths by the neoplastic B cells of SMZL often occurs. In contrast to SMZL in low-weight spleens, in markedly enlarged spleens, residual mantle zone lymphocytes and germinal centers usually are completely obliterated and are replaced by neoplastic marginal zone lymphocytes forming relatively monomorphous, coalescent tumor nodules in the white pulp. Red pulp infiltration usually is present, and, in a few cases, red pulp involvement is extensive leading to almost total destruction of the white pulp with only small, residual, micronodular white pulp segments remaining (

80). A predominant diffuse red pulp pattern of infiltration has been described in cases thought to represent SMZL, but the current WHO classification places such cases in the provisional category of

splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma (SDRPL) (

14,

88).

In other cases, SMZL has a distinct lymphoplasmacytic component; such cases often are associated with a monoclonal gammopathy and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (

64,

89); as discussed earlier, the lymphoplasmacytic form of SMZL is exceedingly difficult to differentiate from splenic LPL (

64,

65). In still other cases of SMZL, increased numbers of blasts or large cells are found, and frank transformation to LBCL may develop (

82,

89,

90 and

91).

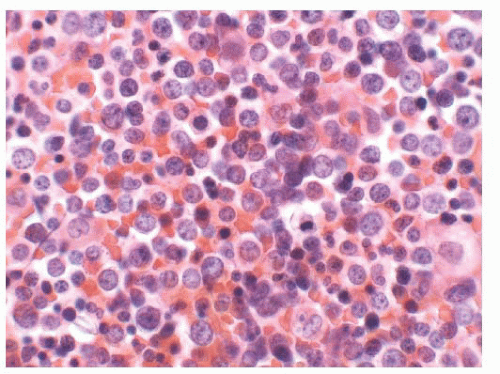

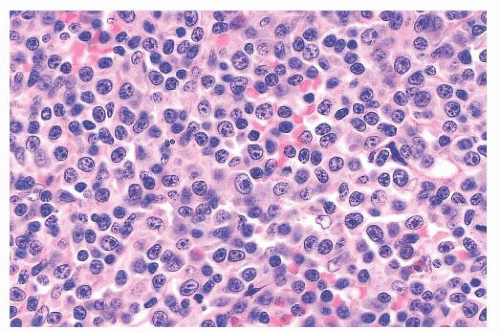

The biphasic pattern of SMZL comprises cases in which the white pulp manifests a prominent central core of small lymphocytes, similar to the cells of MCL, that is surrounded by a peripheral zone of marginal zone-type cells (

Fig. 18.14); both zones are considered part of the same neoplastic clone (

81,

89,

92,

93). The inclusion of biphasic cases in an expanded definition of SMZL arose out of a review of the splenic histologic findings of 37 cases documented as

splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes (SLVL) (

92). In that study, all of the cases of SLVL, including those with a biphasic appearance, were interpreted as being identical to SMZL; these cases currently are categorized as a leukemic form of SMZL (

14,

89,

92,

93).

Leukemic SMZL is a chronic lymphoproliferative disorder that predominantly develops in older adult men. Consistent massive splenomegaly and circulating atypical lymphocytes with cytoplasmic villous projections that often are localized to one pole of the cell are observed (

89). A monoclonal spike is found in the serum or urine in about one-third of patients. About 15% of patients initially thought to represent SLVL have translocation of t(11;14)(q13;q32) and rearrangement of the

bcl-1 locus with increased expression of cyclin D1; the latter patients exhibit a more aggressive clinical course and actually are leukemic MCL cases simulating leukemic SMZL, including the biphasic pattern (

46,

78,

94,

95). The biphasic pattern also may occur in splenic FL and in cases of

marginal zone hyperplasia, such as found in ruptured spleens (

3). One morphologic sign that an expanded marginal zone is neoplastic is the frequent coalescence of adjacent marginal zone segments in SMZL as opposed to the absence of merging of bordering zones in marginal zone hyperplasia; nonetheless, this distinction on histologic examination can be formidable, and immunoglobulin gene rearrangement studies may be required for an absolute diagnosis (

96). One form of marginal zone hyperplasia develops in enlarged spleens derived from patients with

persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, an uncommon benign condition typified by a stable polyclonal CD19-positive, CD5-negative lymphocytosis (

97,

98). In persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis with splenomegaly, the splenic marginal zones are expanded with a biphasic appearance and with associated striking infiltration of the red pulp cords and sinuses by small lymphocytes. The histologic distinction from SMZL is demanding, but unlike SMZL, in persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, the infiltrating B lymphocytes are polyclonal (

97,

98).

SMZL is a B-cell neoplasm expressing various B-cell antigens, IgM and IgD monoclonal immunoglobulin, and bcl-2 protein; CD5, CD10, CD23, CD43, and cyclin D1 generally are not reactive (

46,

79,

69,

81,

84,

89,

90,

91,

92 and

93). The usual absence of CD5 and CD43 expression, as well as cyclin D1, eliminates CLL/SLL and MCL from the diagnosis, and lack of CD10 excludes FL (

46,

64,

78,

95). Cases of SMZL that express CD5 exhibit higher lymphocytosis and more frequent diffuse bone marrow infiltration but otherwise are no different than the more prevalent CD5-negative cases (

99).

Despite similar cytologic features, immunophenotypic profiles, and a shared designation as “marginal zone,” SMZL differs genetically from its extranodal namesake. Similar to node-based MZL, but unlike extranodal MZL of MALT, the splenic cases do not have detectable t(11;18) translocations or

API2-MALT1 fusion transcripts (

100). Patients with SMZL, however, display a variety of complex karyotype abnormalities with frequent gains of 3/3q and 12q as well as genetic losses, specifically 7q and 6q deletions (

101). Deletion of 7q is a characteristic feature of SMZL and its discovery can aid in the differential diagnosis as it is only also detected in some cases of splenic B-cell lymphoma/leukemia, unclassifiable (

81,

102). Recently, mutations in

NOTCH2, a gene required for marginal zone B-cell development, has been discovered in 20% to 25% of cases of SMZL (

103,

104).

NOTCH2 mutations appear exclusive to SMZL and are not present in other B-cell lymphomas and leukemias. Moreover,

NOTCH2 mutations are an adverse clinical finding and associated with increased risk of relapse, histologic transformation, and death (

103). Complexity of the karyotype, 14q aberrations, and

TP53 deletions also are indicative of a poor prognosis (

101). In general, however, SMZL is an indolent lymphoma, and in a report of 309 patients, the 5-year cause-specific survival rate was 76% (

105). Hepatitis C virus may play a role in the lymphomagenesis of SMZL, and some patients benefit from antiviral therapy (

106).

Splenic Diffuse Red Pulp Small B-Cell Lymphoma

Although clearly not a disorder of the white pulp, SDRPL is a provisional category of indolent lymphoma in the 2008 WHO lymphoma classification scheme (

14). This form of lymphoma encompasses the cases that were formerly designated as the diffuse red pulp variant of SMZL and more recently reported as splenic red pulp lymphoma with numerous basophilic villous lymphocytes (

80,

84,

88,

107). Such lymphomas are associated with peripheral blood involvement, often with lymphocytes containing villous projections that are unevenly distributed and with a polar position, as well as bone marrow involvement (

107). In the spleen, the red pulp cords and sinuses are diffusely infiltrated by small to medium-sized, generally round lymphocytes with clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and pale cytoplasm (

Fig. 18.15). Similar to HCL and hairy cell leukemia variant (HCL-V), pseudosinuses and red cell lakes may be present and the white pulp usually is atrophic or obliterated (

93). The neoplastic lymphocytes express CD20 and DBA.44, but unlike HCL, they are CD25-negative and usually CD103, CD123, and annexin A1-negative (

14,

107,

108). Parenthetically, a case of SDRPL with unexplained annexin A1 reactivity has been reported to emphasize that no single molecule is absolutely exclusive to a disease (

109).

Similar to SMZL, SDRPL does not express CD5, CD10, or CD23 and by flow cytometry, CD11c usually is moderately expressed (

110). The cells are IgG-positive and may also express IgD. TRAP staining may occur, and cases often show IgH mutations (

107,

108 and

109). Clonal cytogenetic alterations generally are absent, but this lymphoma may exhibit chromosome 7q deletion, complete trisomy 18, and partial trisomy 3q, but not t(11;14) (

107). As opposed to HCL,

BRAF (V600E) mutation has

not been described in SDRPL (

109,

110 and

111). Although SDRPL is a provisional category in the WHO system, and although usually CD103-negative, it displays considerable overlap with HCL-V so that additional cases and further investigations are required to further delineate these uncommon lymphomas and/or leukemias (

112).

Follicular Lymphoma

Involvement of the spleen by lymphomas with a follicular architecture in lymph nodes is morphologically distinctive. Because these lymphomas usually involve multiple lymphoid sites initially, FL in the spleen, specifically the grade 1 and grade 2 types, similarly embrace virtually every splenic lymphoid site in a multicentric pattern (

1,

113). With extensive disease, the splenic cut surface is peppered by uniformly expanded white pulp nodules that allow ready diagnosis on microscopic examination. The uniform multicentric pattern, when it is coupled with grade 1 or grade 2 cytology, generally implies, but does not absolutely equate with, a follicular architecture in nodes. In the spleen, the neoplastic follicles frequently contain extracellular hyaline deposits (

52).

The era of splenectomy for pathologic staging of non-HL long has passed, but examination of those spleens demonstrated that almost one-third were involved by lymphoma, although the spleens were not palpable on clinical evaluation (

48). The spleens usually were of normal weight and, even though obviously expanded white pulp was absent on either gross or lowpower microscopic examination, a detailed pathologic analysis demonstrated that practically every white pulp segment contained a central core of neoplastic cells, usually centrocytes (

Fig. 18.16) (

113). In this context, grade 2 cases are more difficult to diagnose with confidence because they resemble reactive follicular hyperplasia (

1). Such lymphoma cases, however, usually lack tingible body macrophages; the mantle zone is often diminished or obliterated; no associated plasmacytosis in the red pulp exists; and, paradoxically, the distribution in the white pulp is usually more homogeneous than that observed in hyperplasia. Immunologic markers, such as bcl-2 protein reactivity, are an important adjunct for reaching the diagnosis. The pattern of subtle involvement of the splenic white pulp by FL has come to the fore more recently and referred to as the

architectural preservation pattern (

114). Involvement of the spleen by FL with architectural preservation may be focal and such cases parallel the cases of FL in situ reported in lymph nodes (

114,

115). One extraordinary case of composite FL and MCL in the spleen with each exhibiting an in situ component has been described (

116).

For cases of FL that present primarily with splenic enlargement, the multifocal pattern results in architectural abnormalities with frequent micronodules that efface the splenic red pulp, although the marginal zones at the periphery of the nodules generally are preserved (

117,

118). In this setting, two variants of splenic FL were reported—one was similar to classic FL with grade 1 to 2 morphology, CD10 and

BCL2 expression, t(14;18) positivity, and low proliferative activity, whereas the second tended to be more morphologically high-grade with variable expression of CD10 and

BCL2, t(14;18) negativity, and a higher proliferative rate (

117). The second group, moreover, were more frequently primary lymphomas of the spleen and were at greater risk for transforming to LBCL.

In many spleens involved by FL, regardless of weight, the marginal zones often are conspicuous and may resemble SMZL (

1,

45,

52,

78,

117,

118). The splenic cases containing FL with prominent marginal zone differentiation are similar to cases in lymph nodes (

119,

120). Those cases with concurrent FL and marginal zone differentiation usually exhibit coalescence of adjacent marginal zones. In addition, the central follicular component of the expanded white pulp strongly expresses bcl-2 protein in comparison to the weak reactivity of the peripheral marginal zone component; the t(14;18) translocation may be detected (

119,

120). Molecular genetic studies, however, demonstrate that both components have the same clonal sequences and, together with the

BCL2 rearrangements, indicate that such cases are of follicular center cell origin (

121).