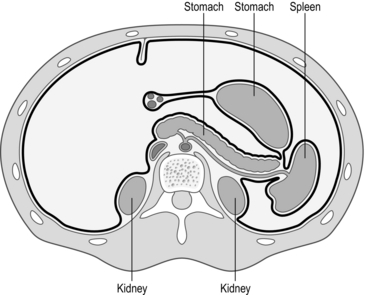

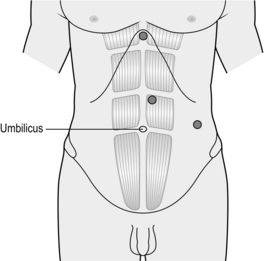

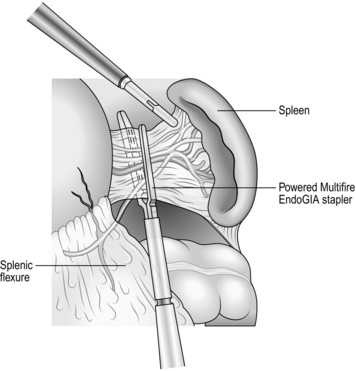

18 1. The spleen is an important organ, with both haematological and immunological functions (Fig. 18.1). Do not lightly remove it. Its haematological functions include the storage, maturation and destruction of red blood cells. Immunologically it produces peptides necessary for the phagocytosis of encapsulated bacteria (Streptococcus pneumonia, Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenza). It is a site of antibody synthesis and may be a reservoir for monocytes that are mobilized following tissue injury. When possible, conserve at least part of the spleen, as opposed to total splenectomy. This may protect against overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI). 2. Elective splenectomy is most commonly carried out for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and haemolytic anaemias. Splenectomy is also required occasionally for other types of splenomegaly with hypersplenism and rarely for conditions such as cyst, abscess, haemangioma or splenic artery aneurysm. Splenectomy is sometimes carried out as a part of other operations, such as total gastrectomy and distal pancreatectomy. Indications are listed in Table 18.1. Table 18.1 3. The indications, preoperative preparation, surgical principles and aftercare are similar for both open and laparoscopic splenectomy. 4. Laparoscopic splenectomy is the standard approach for elective splenectomy for the majority of patients, with operative duration between 60 and 90 minutes, and a hospital stay between 1 and 2 days. There is controversy about its use when treating patients with very large spleens, in splenic trauma and its adequacy for removal of accessory spleens in ITP. 5. There are no absolute contraindications to laparoscopic splenectomy. Spleen size is a major factor. Massive splenomegaly presents difficulties in access, vision and manoeuvring the spleen. Identification of accessory splenic tissue may be less thorough than in open surgery but the long-term results are same. Obesity, peritoneal adhesions and the presence of inflammation also add to the difficulties. 6. The advantages of laparoscopic splenectomy include less postoperative pain, more rapid recovery and fewer respiratory complications when compared to open splenectomy. Long-term follow-up of patients with ITP and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, the two most common indications, have shown identical results to the open approach. The rate of conversion to open splenectomy varies from 0% to 19%. Haemorrhage is the most common reason for conversion, followed by difficulty in mobilizing the spleen due to adhesions or spleen size and injury to adjacent organs. 7. Open splenectomy should be reserved for failure of the laparoscopic technique, emergency splenectomy for trauma and when the necessary laparoscopic skills or equipment are not available. 8. Emergency splenectomy is indicated for traumatic rupture of the spleen, mostly following road traffic accidents and other blunt abdominal injuries. Enlarged spleens are at increased risk of rupture, which may occur spontaneously. Classically, patients are shocked, with pain in the left hypochondrium and shoulder-tip and evidence of left lower rib fractures. Urgent laparotomy is required to control bleeding if the patient remains unstable after initial resuscitation. 9. There is an increasing trend to non-operative management of splenic injuries, particularly in children. Lesser splenic injuries can be managed conservatively with vigilant clinical observation and blood transfusion. Appropriate patients are those less than 60 years of age, haemodynamically stable, with a blood transfusion requirement not exceeding 3–4 units and with computed tomography (CT) scan evidence that the spleen has not been fragmented. A grading system for splenic trauma is summarized in Table 18.2. Table 18.2 A grading system of splenic trauma 10. Accidental splenic injury sustained during operations, such as left hemicolectomy, was formerly an indication for splenectomy, but the bleeding can usually be controlled by lesser means. Intra-operative splenic injury occurs in approximately 0.01% of open laparotomies and the incidence increases following reoperative surgery. Up to 10% of splenectomies performed are secondary to iatrogenic injury. 11. Preoperative splenic artery embolization may reduce the risk of intra-operative haemorrhage. This percutaneous radiological technique has been described in conjunction with open splenectomy, primarily in cases of massive splenomegaly. Other advantages of embolization include reduced splenic volume and avoidance of the risk of arteriovenous fistula from stapling across the splenic hilum. Embolization is most frequently performed on the day of surgery to reduce the discomfort associated with splenic ischaemia and infectious complications. 1. Vaccinate patients 2 weeks prior to surgery to decrease the risk of post-splenectomy sepsis. Immunize against pneumococcal infections (Pneumovax II 0.5 ml IM/SC, Sanofi Pasteur) and Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) and meningococcus group C infections (Menitorix 0.5 ml IM, GlaxoSmithKline). 2. Preoperative percutaneous splenic artery embolization is used in some units to reduce the risk of bleeding or decrease significant splenomegaly. 3. Give antibiotics (first generation cephalosporin) perioperatively. Ensure patients are adequately hydrated before surgery. Pneumatic compression stockings are routinely employed. 4. Correct anaemia, thrombocytopenia and coagulopathies preoperatively. Reserve packed red blood cells for all patients and platelets for thrombocytopenic patients. Preoperative medical therapy (e.g. IgG therapy or increasing steroids) may elevate platelet count transiently in ITP cases. Give parenteral steroid cover in patients with ITP or other haematological disease on long-term corticosteroids. Involve the haematologist in the pre- and postoperative care of the patient. If the platelet count is low, transfuse platelets intra-operatively after ligation of the splenic artery to prevent rapid sequestration. 5. A nasogastric tube may be needed to decompress a distended stomach, but is not routinely required. 6. Ensure you have explained and documented the advice given to patients on the risks of post-splenectomy sepsis. 1. Position the patient in a left lateral position. This position facilitates retraction of the stomach and omentum away from the spleen and improves access. 2. Create a pneumoperitoneum using a Veress needle technique at the umbilicus or an open technique at the camera port site. Exact port placement depends on the size of the spleen. For a normal-sized spleen place the 11-mm camera port above the umbilicus and to the left of the midline. Place a 5-mm port in the epigastrium and a 12-mm port for stapler and retrieval bag in the left lateral position as shown in Figure 18.2. An additional port for a fan retractor may be necessary. 1. Perform a systematic exploration looking for splenunculi (small nodules of splenic tissue away from the main body of the spleen), which may be found anywhere in the abdominal cavity, but are commonly located at the hilum of the spleen and adjacent to the tail of the pancreas. When identified, if the splenectomy is performed for conditions in which blood cells are sequestered in the spleen, remove all splenunculi immediately so they are not lost during subsequent dissection. 2. Use scissor diathermy or a harmonic scalpel to divide any omental adhesions to the lower pole of the spleen and the splenocolic ligament. 1. Avoid grasping the spleen directly. Use open Johannes forceps to gently retract the spleen medially. Divide splenic attachments about 1 cm away from the spleen and use these attachments to retract the spleen. Continue the dissection laterally to divide the attachments to the lateral sidewall. Continue the dissection, using the harmonic scalpel or hook diathermy, from the inferior pole of the spleen to the superior pole. As the dissection progresses the spleen becomes more mobile and can be moved medially to expose the back of the splenic hilum. 2. Leave the splenophrenic ligaments at the top of the spleen to stop it falling into the abdominal cavity: these are divided once the spleen has been placed in the retrieval bag, immediately prior to its removal. It is important to clear the back of the splenic hilum carefully at this stage and identify the tail of the pancreas to avoid damaging it at a later stage. 3. Return to the lower pole of the spleen and begin the medial dissection by dividing the serosa over the hilar vessels (Fig. 18.3). As you pass towards the upper pole of the spleen you will encounter the short gastric vessels. Divide these now with the harmonic scalpel. Alternatively, they can be divided together with the hilar vessels using a vascular stapler.

Spleen

Appraisal

Red cell causes

Hereditary spherocytosis

Sickle cell disease

Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

Thalassaemias

White cell causes

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Leukaemia

Platelet causes

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

TTP

Other causes

Trauma

Cysts

Abscesses

Grade I: capsular injury not actively bleeding

Non-operative

Grade II: capsular or minor parenchymal injury

Topical haemostatic agent

Grade III: moderate parenchymal injury

Suturing and haemostatic agent

Grade IV: severe parenchymal injury

Partial splenic resection

Grade V: Extensive parenchymal injury

Splenectomy

Prepare

LAPAROSCOPIC SPLENECTOMY

Access

Assess

Action

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree