Splanchnic Denervation of the Pancreas for Intractable Pain

Keith D. Lillemoe

Thomas J. Howard

Introduction

The treatment of intractable pain in patients with either chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancers is one of the most challenging clinical situations faced by the surgeon. The pancreas is a highly innervated visceral organ incorporating both exocrine and endocrine tissue into an integrated functional unit. The autonomic nerves orchestrating this function, in addition to providing neurohumoral regulation, are sensitive to both chemical and mechanical stimuli that can be transmitted back to the central nervous system as pain. The precise molecular pathophysiology of pancreatic pain remains incompletely understood and most of the data seeking to clarify this issue comes from studies in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Based on these investigations, two general theories for the genesis of pain have been proposed: (a) increased pancreatic duct pressure with tissue hypertension and poor microvascular perfusion or (b) pancreatitis or cancer-associated neuritis with alterations in the perineural sheath. Both theories have their advocates; however, neither is sufficiently comprehensive to explain pain generation in all clinical circumstances. It is entirely possible, as with most complex, neural-mediated pain syndromes, that potential overlap and considerable synergism exists between these two competing theories. For the purpose of our discussion in this chapter, regardless of the exact pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the genesis of pain, sensory autonomic nerve endings located in the pancreatic parenchyma transmit neural afferent information to the celiac ganglion. The celiac ganglion plexus of nerves then serves as a way station for pain impulses traveling toward the central nervous system where they are processed, localized, and interpreted. The greater (T5 to T10) and lesser (T10 to T11) splanchnic nerves are composed of postganglionic sympathetic nerve fibers that carry visceral sensory impulses to the spinal cord, which are then transmitted on to the thalamus and subsequently to the cerebral cortex.

Pain referable to the pancreas is commonly described by the patient as either a sharp stabbing pain or a dull boring pain, localized in the midepigastrium or left upper quadrant. This pain frequently radiates to the back between the T12 and L2 dermatomes. Occasionally, the pain becomes so severe that it results in the patient doubling over, causing them to bend forward at the waist in a knee-to-chest configuration, the so-called pancreatitis position. The pain occurs predominately postprandial, at least early in its course, and is associated with nausea. Colicky pain is unusual in this setting and should arouse suspicion of a biliary tract rather than pancreatic etiology. Pain severity differs markedly from patient to patient, and severity can also vary considerable from day to day in the same patient. In both chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer, as the disease advances the pain becomes progressively more constant, unrelenting, and debilitating.

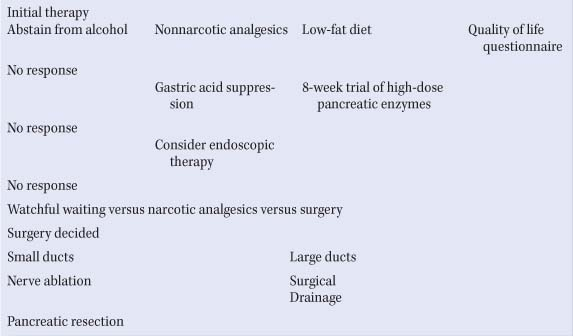

The treatment of pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis has been addressed in a position statement by the American Gastroenterologic Association (AGA) (see Table 1). In this algorithm, total abstinence from alcohol and initial pain management with nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antidepressants, and a low-fat diet are recommended. Imaging studies should be carried out to look for treatable causes of pain (i.e., pancreatic pseudocyst, biliary stricture, duodenal stenosis, or peptic ulcer disease). If the initial treatments rendered prove ineffective, an 8-week course of oral pancreatic enzyme supplementation and acid suppression is instituted. Failure of these treatments leads to the use of opioid analgesics and consideration should then be given to either endoscopic or surgical management. Imaging studies should also be used to categorize patients with chronic pancreatitis into anatomic (large duct, small duct, minimal change) and morphologic (enlarged hypertrophic pancreatic head, small pancreatic head, obstructive pancreatitis) variants. Once categorized, patients can be treated rationally with the most appropriate type of endoscopic or surgical intervention. If they have failed these interventions, lack an anatomic target for endoscopic or surgical treatment (i.e., pancreatic duct stricture, dilated pancreatic duct), or refuse endoscopic or surgical interventions, then they are candidates for celiac plexus neurolysis (CPN).

Table 1 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Medical Position Statement on the Treatment of Pain in Chronic Pancreatitis | |

|---|---|

|

For patients with pancreatic cancer, use of transdermal or long-acting narcotic analgesics that provide a steady-state basal plasma level, supplemented with the intermittent use of short-acting narcotic analgesics for breakthrough pain, is the preferred initial treatment method. Antidepressant medication is also used to supplement pain management strategies in patients with pancreas cancer or chronic pancreatitis.

Percutaneous and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–directed CPN are useful, minimally invasive adjuncts to achieve pain relief in patients with either chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma. Whereas celiac plexus block (CPB) refers to the injection of steroids, with or without a local anesthetic, to temporarily inhibit celiac plexus function and reduce inflammation and pain, CPN involves the injection of either cytotoxic ethanol or phenol, occasionally in combination with a local anesthetic, to permanently destroy nerve fibers and facilitate lasting pain relief. In this chapter, our focus will be on permanent neurolytic procedures.

Percutaneous and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–directed CPN are useful, minimally invasive adjuncts to achieve pain relief in patients with either chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma. Whereas celiac plexus block (CPB) refers to the injection of steroids, with or without a local anesthetic, to temporarily inhibit celiac plexus function and reduce inflammation and pain, CPN involves the injection of either cytotoxic ethanol or phenol, occasionally in combination with a local anesthetic, to permanently destroy nerve fibers and facilitate lasting pain relief. In this chapter, our focus will be on permanent neurolytic procedures.

The celiac ganglion innervates the upper abdominal viscera and is the largest plexus of nerves in the abdominal aortic sympathetic plexus. It contains both preganglionic and postganglionic sympathetic fibers, preganglionic parasympathetic fibers, and visceral afferent (pain) fibers. The celiac plexus is composed of bilateral celiac ganglia, located in front of and on both sides of the abdominal aorta at the level of the celiac artery. Plexus fibers cross in front of the aorta both above and below the celiac axis. Organs innervated by the celiac ganglia include the stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, adrenal glands, kidneys, and intestines to the level of the transverse colon. The sympathetic plexus ganglia vary in number from one to five on each side of the aorta, and range from an aggregate size of 0.5 cm to 4.5 cm. Without extensive dissection, the origin of the celiac artery can be identified intraoperatively by palpation of the common hepatic and splenic arteries, the two most consistent arterial branches off the celiac artery. Radiographically, the plexus can be found by identification of both the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries.

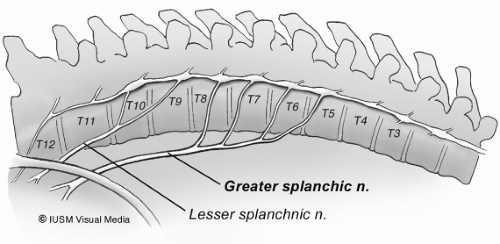

The splanchnic nerves, usually three (greater, lesser, and least), consist primarily of preganglionic sympathetic and accompanying visceral afferent fibers. These nerves vary much in their origin; however, the greater splanchnic nerves usually arise from the fifth through ninth thoracic ganglia (Fig. 1). The unison of these roots forms a nerve of considerable size (larger than the continuation of the sympathetic trunk into the abdomen) that descends on the front of the vertebral column and pierces the muscular part of the diaphragm to end in the celiac ganglion. The lesser splanchnic nerve usually arises from the 9th and 10th or last two thoracic sympathetic ganglia. It runs parallel and medial to the greater splanchnic nerve but lateral to the sympathetic trunk. This nerve trunk is constituted at or above the level of the 10th thoracic vertebra, and descends along the spine where it is bound by the parietal pleura. The lesser splanchnic nerve generally supplies the submesenteric organs and forms from the trunks of the 10th and 11th thoracic ganglia and runs parallel to the greater splanchnic nerve in the chest. Both nerves penetrate the crus of the diaphragm and enter the abdomen. The greater splanchnic nerve ends in the celiac ganglia, and the lesser splanchnic nerve ends in the aorticorenal ganglion. The vagus nerves run in the lower thoracic cavity along the esophagus below the parietal pleura. The role of the vagal fibers in the transmission of pain sensation from the pancreas is unclear. Bilateral vagotomy has been advocated in early series of CPN as a method of increasing the completeness of splanchnic denervation. Currently, most surgeons limit their operation to the splanchnic nerves as the postvagotomy sequelae of delayed gastric emptying and diarrhea can often be formidable.

Pancreatic cancer: Survival of patients with locally advanced, unresectable pancreatic cancer is 6 to 12 months while patients with metastatic disease to the liver or peritoneal cavity survive approximately 3 to 6 months. The majority of patients in both groups will have pain requiring increasing doses of narcotic analgesics during the course of their illness. A systematic review examined the efficacy and safety of CPN compared with standard treatment in five randomized controlled trials involving 302 patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. The primary outcome was pain, measured on a 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS). CPN was associated with lower VAS scores for pain at 2, 4, and 8 weeks (weighted mean difference (WMD), 0.60; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.82 to -0.37). Opioid usage (in mg/dL oral morphine) was also reduced at 2, 4, and 8 weeks (WMD, 85.9, 95% CI, -144.0 to 127.9). In cases in which pancreatic cancer is found to be inoperable based on preoperative imaging studies, nonsurgical techniques for pain control are indicated, avoiding the need for laparotomy. However, in those patients where the tumor is found to be unresectable at the time of laparotomy, intraoperative chemical CPN should be done in conjunction with appropriate surgical palliative procedures such as biliary bypass and/or gastrojejunostomy. This procedure is indicated whether or not the patient has significant pain at the time of surgery as the natural history of the disease includes pain that becomes progressively more severe and unrelenting as the malignancy progresses. The same technique is applicable whether the tumor arises in the head, body, or tail of the gland. There are currently no good data to support prophylactic CPN in patients who have undergone a complete R0 surgical resection, despite the fact that almost 50% of such patients will eventually develop retroperitoneal tumor recurrence as a component of disease relapse and pain recurrence with this development.

There is little indication for open laparotomy for the sole purpose of performing CPN in patients who are otherwise not candidates for surgical resection or palliation based on the extent of their disease, age, or medical disability. The availability of percutaneous CPN using fluoroscopic or computed tomographic (CT) guidance or using EUS to visualize the celiac axis has eliminated the need for this laparotomy solely for this purpose. In patients with pancreatic cancer and unmanageable pain who are unable to be adequately palliated by percutaneous or endoscopic CPN, bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy (BTS) should be considered as complete transaction of the afferent nerves above the level of the celiac axis can often be beneficial in this situation.

Chronic pancreatitis: Patients with small duct pancreatitis without an endoscopic or surgical target (i.e., pancreatic duct stricture, dilated pancreatic duct, enlarged hypertensive pancreatic head) or patients who have failed first-line endoscopic or surgical treatment are candidates for BTS. Currently, there are little data to support the concomitant use of CPN as an adjunct for postoperative pain control during an operation where either a resection (Whipple, duodenal-sparing pancreatic head resection) or drainage procedure (Puestow) is being performed for patients with chronic pancreatitis and recurrent abdominal pain. If the patient is carefully selected and the operation is appropriately matched to the ductal anatomy and pancreatic morphology, a 70% to 80% long-term success rate in achieving postoperative pain control can be anticipated. In those patients who fail to achieve pain relief, or in patients who develop recurrent pain following operation, radiographic and endoscopic investigation of postoperative anatomy should be carried out to identify an anatomic cause of failure. If there is no anatomic explanation for their recurrent symptoms (biliary stricture, fluid collection, pancreatic duct stricture, disease progression), percutaneous or EUS-guided CPN, or BTS, should be considered as an adjunct to the patient’s ongoing pain management.

Open Cpn

Open CPN has become a standard approach to pain management in patients undergoing laparotomy for unresectable pancreatic cancer. The procedure was first described by Copping and colleagues in 1969. In an update of their series in 1978, including 41 patients with pain due to pancreatic cancer, 88% of patients experienced relief of pain postoperatively. Most patients underwent palliative biliary and gastrojejunal bypass at the same operation. These results were compared with a group of historic controls in which only 21% of patients had pain control after similar palliative procedures. Since that time, this procedure has been advocated by a number of authors in anecdotal reports describing successful control of pain in the majority of patients. In 1993, a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study of this treatment was completed with results demonstrating that open chemical neurolysis with a 50% alcohol solution significantly reduces or prevents pain in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer when compared with a placebo injection with saline. This beneficial effect was observed in all randomized patients including both subgroups of patients, those with and without preoperative pain. Interestingly, this study also showed a significant improvement in survival in patients with significant preoperative pain who received the alcohol neurolysis when compared with placebo, implying that better pain control and a reduced requirement for narcotic analgesics may prolong survival as well as improve the quality of life in patients with end-stage pancreatic cancer.

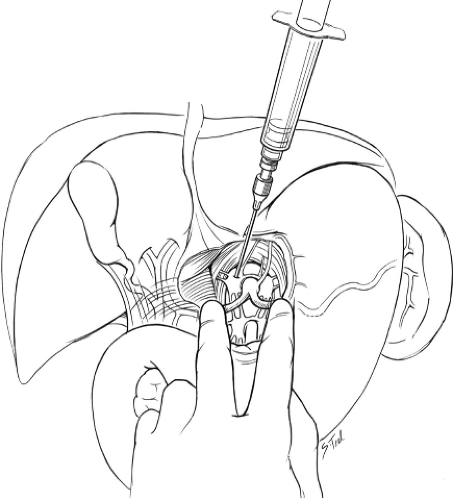

Fig. 2. Intraoperative celiac plexus neurolysis. After incising the avascular area of the hepatogastric ligament, the celiac trunk is palpated by placing the surgeon’s left index finger on the splenic artery and the left third finger on the common hepatic artery while steadying their hand by abutting their thumb to the left lateral aspect of the aorta. The surgeon’s right hand uses the 10-cc syringe to inject 50% ethanol into four quadrants around the celiac axis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|