Specific Infections

SYED A. HODA

A wide variety of infections caused by fungi, parasites, bacteria, and viruses can afflict the breast. It is distinctly uncommon for the breast to be exclusively involved, and most such diseases involve the breast secondary to systemic involvement.

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Clinically apparent mycotic infections of the breast are uncommon, even in patients who are immunocompromised as a consequence of an underlying illness or therapy.

Histoplasmosis

Infection with Histoplasma capsulatum is endemic in some regions of the United States and in Africa, where many individuals have evidence of healed granulomatous lesions primarily in the lungs, liver, and spleen. Calcified granulomas have been described in the breast, and there have been rare instances of localized mammary Histoplasma infection.1,2 All were in young women. Each patient presented with a single, unilateral mass, which clinically suggested a neoplasm. Two lesions were painful, and inflammatory changes involved the skin in one case.1 Clinical evaluation in two cases failed to demonstrate evidence of systemic H. capsulatum infection, but one patient had an elevated complement fixation test. The excised tumors proved grossly to be multinodular abscesses up to 3 cm in diameter that contained necrotic material. Histologically, as in this reported case, the lesions consist of confluent necrotizing granulomas similar to those of nonspecific granulomatous lobular mastitis in which the 2- to 4-µm yeast forms of H. capsulatum can be demonstrated by methenamine silver reaction (Fig. 4.1A-D). Another 55-year-old woman presented with a mass in the lateral mammary region that proved to be enlarged lymph nodes without involvement of breast parenchyma. H. capsulatum was isolated in culture and seen in tissue sections.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is endemic in certain regions of the United States and in Africa.5,6 A 4-cm unilateral breast abscess that contained organisms histologically consistent with the broad-based budding yeasts of Blastomyces dermatitidis was excised from the para-areolar region of a 30-year-old woman.2 She had no other evidence of infection and remained well 8 years later. Mammography reveals well-demarcated lesions. Large nodules may become cavitary with an air-fluid level.5 The diagnosis is usually made when Blastomyces sp. is cultured from skin lesions or from a fineneedle aspiration (FNA) cytology specimen of the breast.4 One patient also had a tumorous pulmonary lesion and another had a pleural effusion.5,6 The breast and lung lesions may resolve completely with amphotericin therapy.5,6

Cryptococcosis

An extraordinary example of cryptococcal mastitis was described by Symmers.7 The patient underwent mastectomy for a mistaken diagnosis of mucinous mammary carcinoma. The specimen was preserved in a museum and studied microscopically 61 years after surgery, at which time there was no evidence of carcinoma, but the breast was found to be infected with Cryptococcus—an encapsulated yeast with worldwide distribution. The patient died 37 years after mastectomy of an unrelated cause with no evidence of recurrent cryptococcosis. In another case, disseminated cryptococcal infection with involvement of the breasts was detected at autopsy in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus.2 Ramos-Barbosa et al.8 reported mammary cryptococcal infection that presented as a cystic lesion in a 46-year-old woman who was under treatment with corticosteroids for sarcoidosis.

Aspergillosis

Unilateral and bilateral mammary aspergillosis has been reported at the site of prosthetic augmentation implants.9,10 Involvement of the nipple by Aspergillus flavus in a 51-year-old woman apparently followed traumatic rupture of a superficial keratotic cyst.11

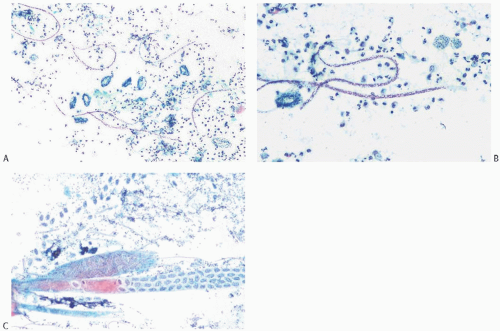

FIG. 4.1. Mycotic mastitis. Histoplasmosis. A,B: A fibrotic granuloma with mixed inflammatory cell reaction is present amidst breast tissue. C: Yeast forms of H. capsulatum are evident in the reactive infiltrate around the granuloma on methenamine silver reaction. D: Chromomycosis. The sample shown was obtained by FNA (Courtesy of Kusum Kapila, MD, and Kusum Verma, MD). |

Chromomycosis

Infection of the nipple by Fonsecaea pedrosoi, and of mammary skin by Phialophora verrucosa, has been described.12,13 Both fungi cause chromomycosis (also called chromoblastomycosis). On histology, the pigmented yeast forms resemble “copper pennies.” The lesion in both cases formed a plaque with crusting. Biopsy revealed epidermal hyperplasia containing characteristic fungal hyphae, which may also be seen in an FNA specimen (Fig. 4.1E).

Coccidioidomycosis

Isolated breast involvement by Coccidioides immitis has been reported.14 The patient was a 60-year-old woman under treatment with prednisone for temporal arteritis. Clinical examination revealed a circumscribed, 1.0-cm breast tumor with sharply defined borders on mammography. The excised mass consisted of a rim of granulation tissue around a necrotic center, which contained spherules characteristic of C. immitis. No pulmonary lesions were identified. Pregnancy is a well-recognized factor for the precipitous (and occasionally fatal) dissemination of the disease.15,16

PARASITIC INFECTIONS

Filariasis

Mammary filariasis caused most frequently by Wuchereria bancrofti has been reported from South America, China, and South Asia, where infection with this organism is endemic.17,18 Involvement of the breast generally occurs as a late manifestation of low-grade, clinically inapparent infection as evidenced by emigrants and travelers found to have mammary filariasis as late as 3 years19 and 6 years20 after last exposure to infection. Microfilariae are sometimes demonstrable in thick blood smear samples taken around midnight, but some investigators have failed to detect microfilaremia in patients with breast lesions.19,20 Microfilariae have been detected in nipple secretions, suggesting that communication may become established between ducts and dilated, ruptured lymphatics (lymphovarix).21

The patient typically presents with a solitary, nontender, painless unilateral breast mass. The upper outer quadrant is the most common site.17,20 Many of the lesions involve subcutaneous tissue. The resultant hard mass with cutaneous attachment, sometimes accompanied by inflammatory

changes, may be clinically indistinguishable from carcinoma.22 In this setting, axillary nodal enlargement caused by filarial lymphadenitis further complicates the differential diagnosis.23 In endemic areas, mammary filariasis may be detected coincidentally in patients with breast carcinoma.18 Viable microfilariae can be detected in the breast by ultrasound examination if they produce a distinctive pattern of movement referred to as the “filaria dance sign.”24 Mammographically detected calcifications attributed to W. bancrofti and Loa loa infection have been described as having a spiral or serpiginous configuration.22,25,26

changes, may be clinically indistinguishable from carcinoma.22 In this setting, axillary nodal enlargement caused by filarial lymphadenitis further complicates the differential diagnosis.23 In endemic areas, mammary filariasis may be detected coincidentally in patients with breast carcinoma.18 Viable microfilariae can be detected in the breast by ultrasound examination if they produce a distinctive pattern of movement referred to as the “filaria dance sign.”24 Mammographically detected calcifications attributed to W. bancrofti and Loa loa infection have been described as having a spiral or serpiginous configuration.22,25,26

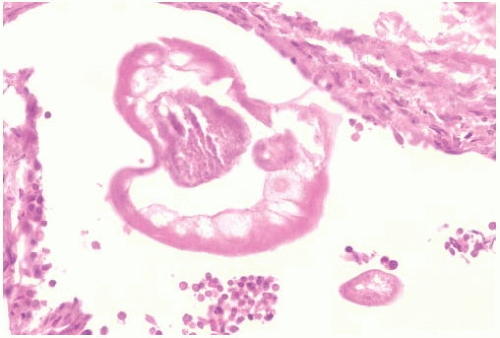

Microfilariae and gravid adult worms can be detected in fine-needle aspirates from breast lesions (Fig. 4.2).27 The aspirate usually contains numerous eosinophils as well as other inflammatory cells, and features of a granulomatous reaction may be evident.

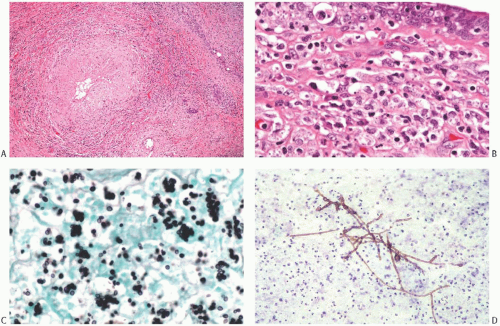

The majority of the filaria-associated mammary masses measure between 1 and 3 cm in diameter and are composed of firm, gray or white tissue that tends to merge with the breast parenchyma. Rarely an abscess can develop. Thread-like white worms are sometimes evident grossly in the lesion.17 Microscopic examination of the excised mass typically reveals adult filarial worms, in varying stages of preservation (Fig. 4.3). Granulomatous reaction is most pronounced in areas of degenerating organisms. Eosinophils are a prominent feature. Degenerative changes may lead to the formation of eosinophilic abscesses (Fig. 4.4).

Female worms are about three times the size of male worms. Eggs in varying stages of maturation are identifiable in the uterus of adult females. Microfilariae may be seen within the uterus and in surrounding inflammatory tissue and appear as nuclei arranged in a linear pattern. Rarely, granulomatous lesions in the breast have contained only microfilariae.17 Fully degenerated worms are likely to become calcified. Adult worms and microfilariae may also be found in axillary lymph nodes.17,23

The diagnosis of mammary involvement by W. bancrofti is dependent on the specific microscopic structural features of the worm, eggs, and microfilariae, as well as clinical information. Zoonotic filarial infections of the breast are much less common than those caused by W. bancrofti. The microfilariae are transmitted to humans by mosquito vectors, including Aedes and Anopheles species. Infections of the breast have been reported most often from North America, Europe, and Asia.28,29,30,31 Lesions caused by zoonotic filariasis occur predominantly in the subcutaneous tissue, the conjunctiva, and the lungs.28

The organism responsible for most examples of mammary dirofilariasis is Dirofilaria repens,28,29,30,31,32 which ordinarily infects cats and dogs, but infestation of humans by Dirofilaria tenuis, which primarily infects raccoons, has been reported.30 The lesions occur in the subcutaneous tissue or superficial mammary parenchyma. Infection of the breast typically presents as a discrete firm to hard nodule that measures approximately 1 cm in diameter. The lesions tend to be

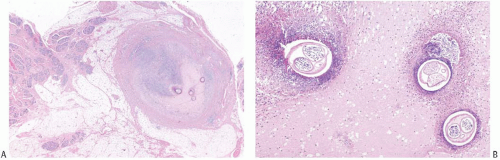

superficially located. The excised specimen usually consists of a firm fibrous tissue mass with a central cavity (Fig. 4.5) in the subcutaneous or breast tissue. Microscopically, cross sections of the adult worm are found in the central necrotic area accompanied by an intense inflammatory reaction, which includes many eosinophils. A fibrous capsule with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils encompasses the necrotic zone. The diagnosis of mammary dirofilariasis is usually not suspected until the excised lesion has been examined microscopically. However, in one case, “a threadlike object was seen projecting from the puncture site” after an attempt at needle aspiration, and a 2-cm organism was pulled out by forceps.29

superficially located. The excised specimen usually consists of a firm fibrous tissue mass with a central cavity (Fig. 4.5) in the subcutaneous or breast tissue. Microscopically, cross sections of the adult worm are found in the central necrotic area accompanied by an intense inflammatory reaction, which includes many eosinophils. A fibrous capsule with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils encompasses the necrotic zone. The diagnosis of mammary dirofilariasis is usually not suspected until the excised lesion has been examined microscopically. However, in one case, “a threadlike object was seen projecting from the puncture site” after an attempt at needle aspiration, and a 2-cm organism was pulled out by forceps.29

FIG. 4.3. Filariasis. A,B: An abscess containing cross sections of gravid female W. bancrofti in the subcutaneous tissue adjacent to mammary parenchyma. |

Another organism responsible for mammary filariasis is Onchocerca volvulus, which is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Infection is transmitted by the black fly, Simulium. Microfilariae localized in the skin, breast, and other sites induce an inflammatory reaction. Dead filarial worms tend to calcify and to appear as serpiginous strands in a mammogram.33

Other Parasites

Infection of the breast by Schistosoma japonicum has been reported in two women 35 years old34,35 and in a third who was 50.36 Calcifications detected by mammography proved to be calcified ova embedded in breast parenchyma in each case. The 50-year-old woman had a painless mass at the site of the mammographic abnormality, which consisted of “branching microcalcifications suggestive of carcinoma in situ.”36 The calcified ova found in a biopsy specimen were identified as S. japonicum. Similar lesions have also been escribed in the subcutaneous tissue.37 Mammary parenchymal involvement and cutaneous ulceration by Schistosoma mansoni have also been described38,39 (Fig. 4.6).

Several examples of mammary coenurosis and cysticercosis, infections caused by the larval stages of tapeworms, have been described. Coenurosis results from infestation by tapeworms related to Taenia sp., which is responsible for cysticercosis. In one case, a 38-year-old Canadian woman developed a 6-cm mass in the upper inner quadrant of her left breast.40 At surgery, the lesion, which also involved the pectoral muscle, contained gelatinous material and cysts with scolices typical for tapeworms. An axillary mass that clinically resembled metastatic carcinoma in another patient proved to be cystic coenurus infection caused by Taenia multiceps.41 No source of infection was identified in either case.

Mammary cysticercosis caused by Taenia solium has also been reported42,43,44,45 (Fig. 4.7). In a 25-year-old woman, the infestation resulted in the formation of a circumscribed nodule near the areola.43

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree