Fibroepithelial Neoplasms

EDI BROGI

SCLEROSING LOBULAR HYPERPLASIA (FIBROADENOMATOID MASTOPATHY)

Clinical Presentation

This benign proliferative lesion presents as a localized tumor spanning up to 8 cm in diameter (mean, approximately 4 cm), usually in the upper outer quadrant of the breast.1,2 Skin retraction and pain are absent, but the tumor may be tender. The most frequent mammographic finding is a well-defined mass. Microcalcifications may be present.3 Asymptomatic examples have been detected by mammography.2 The imaging characteristics are not sufficiently specific to distinguish sclerosing lobular hyperplasia from a fibroadenoma (FA).

Gross and Microscopic Pathology

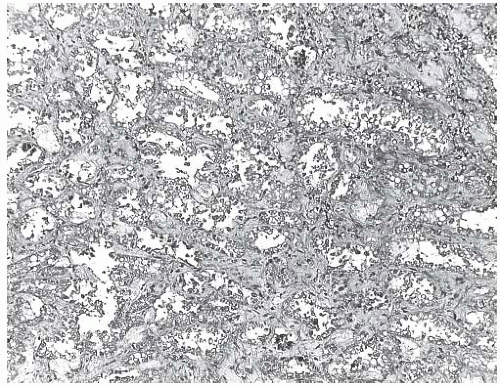

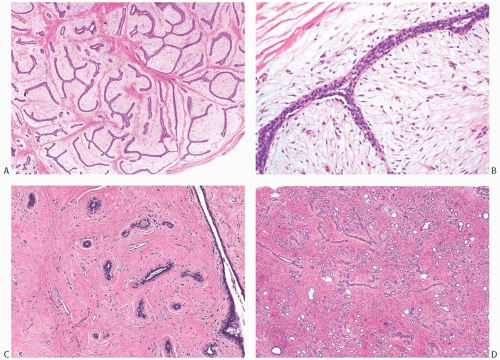

The excised specimen is composed of firm, nodular tan tissue with a granular appearance on the cut surface. Microscopic examination reveals enlarged lobules composed of an increased number of intralobular glands. The intralobular stroma is collagenized with loss of stromal mucopolysaccharide, and the interlobular stroma shows variable sclerosis (Fig. 8.1). Individual lobules and groups of lobules have the appearance of miniature FAs with a prominent glandular component. The lobular glands have distinct epithelial and myoepithelial components, each composed of a single layer of cells. Secretory activity may be present, and calcifications are typically not formed.

Sclerosing lobular hyperplasia or fibroadenomatoid mastopathy is found in breast tissue surrounding about 50% of FAs and most phyllodes tumors (PTs).1 This association suggests that the same or related factors contribute to the pathogenesis of these lesions. The ratio of sclerosing lobular hyperplasia to FA in one series was 9.3:1, a relationship consistent with the hypothesis that some FAs arise as localized foci of accelerated proliferation in a background of sclerosing lobular hyperplasia.1 Because a FA or PT presents clinically as a dominant mass, its association with sclerosing lobular hyperplasia may be overlooked clinically and pathologically. The occurrence of sclerosing lobular hyperplasia forming a mass by itself is an uncommon event.

Treatment and Prognosis

A diagnosis of sclerosing lobular hyperplasia is usually not made preoperatively, and most of these patients have a clinical diagnosis of FA or fibrocystic change (FCC). Excisional biopsy of the palpable lesion is adequate therapy. There is no systematic follow-up study documenting the frequency of recurrence. Anecdotal experience suggests that recurrence in the form of a FA is very infrequent but that this condition may contribute to the syndrome of multiple recurrent FAs.

FIBROADENOMA

These benign tumors arise from the epithelium and stroma of the terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU). They are the most common breast tumors clinically and pathologically in adolescent and young women.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for developing FAs have not been investigated extensively. Canny et al.6 carried out a case-control study of 251 women with FAs in Connecticut. Women younger than 45 years with FAs were less likely than controls to have taken contraceptives. This difference was not observed in women older than 45 years when a FA was diagnosed. Conversely, there was a significant positive correlation between FAs and exogenous estrogen replacement therapy regardless of age. The risk of developing a FA among users of oral contraceptives is not related to the extent of epithelial atypia present in the FA.7 A case-control study of Australian women reported a direct association between contraceptive use before age 20 and the risk of developing a FA.8 Risk was inversely related to the body mass index and the number of full-term pregnancies. Use of estrogen replacement therapy was not significantly related to the presence of FAs in this series.

Although lesions diagnosed as juvenile FAs have been reported in patients with the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome,9,10 the histologic features of the FA lesions were not described in detail or illustrated, and the clinical appearance was consistent with other entities such as pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH). In one instance,9

a 5-cm unilateral mass excised from the left breast of a 7-month-old girl was diagnosed as “a benign juvenile FA.” Ten months later, a recurrent nodule was excised and classified as “a juvenile intracanalicular FA.” Another female patient presented with bilateral macromastia at the age of 12.10 Imaging revealed “multiple, well-defined hyper dense masses in both breasts.” Six masses were excised from the right breast, and a left subcutaneous mastectomy yielded a 2185-g specimen. The pathology findings were described as “benign breast parenchyma with epithelial hyperplasia and stromal fibrosis, which was consistent with FAs.” It is noteworthy that the authors of the latter case report commented on the similarity of their patient’s condition to “juvenile gigantomastia” that is almost always a manifestation of PASH (see Chapter 38).

a 5-cm unilateral mass excised from the left breast of a 7-month-old girl was diagnosed as “a benign juvenile FA.” Ten months later, a recurrent nodule was excised and classified as “a juvenile intracanalicular FA.” Another female patient presented with bilateral macromastia at the age of 12.10 Imaging revealed “multiple, well-defined hyper dense masses in both breasts.” Six masses were excised from the right breast, and a left subcutaneous mastectomy yielded a 2185-g specimen. The pathology findings were described as “benign breast parenchyma with epithelial hyperplasia and stromal fibrosis, which was consistent with FAs.” It is noteworthy that the authors of the latter case report commented on the similarity of their patient’s condition to “juvenile gigantomastia” that is almost always a manifestation of PASH (see Chapter 38).

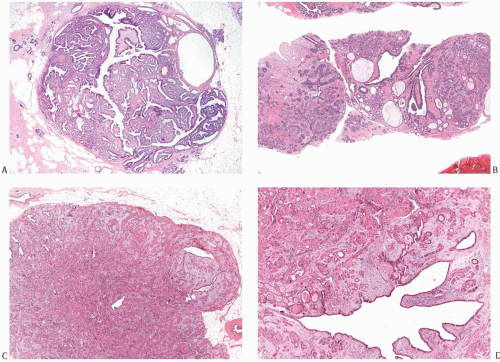

FIG. 8.1. Fibroadenomatoid mastopathy (sclerosing lobular hyperplasia). A: The tumor is composed of enlarged lobules. B: In this case, one lobule with sclerotic stroma has the appearance of a small FA. C,D: Two views of another example of fibroadenomatoid mastopathy. |

Multiple bilateral FAs diagnosed simultaneously in two adolescent female identical twins have been described, but the lesions were not subjected to cytogenetic analysis.11 Women with Carney syndrome may develop myxoid FAs,12 but it is unknown what percentage of women with myxoid FA also have Carney syndrome.

Rare examples of FAs have been reported in men.13,14,15,16,17,18 FAs arising in the male breast usually occur in the context of gynecomastia. Most have been associated with treatment with various medications, such as estrogen or hormone modulators in patients with prostatic carcinoma, hormone treatments in male-to-female transsexuals, and use of spironolactone. It is exceedingly unusual for a FA to arise in the male breast in the absence of gynecomastia and/or the administration of predisposing drugs. Shin and Rosen19 reported a case of bilateral FAs with digital fibroma-like inclusions in a 66-year-old man treated for prostate carcinoma.

Patients who receive cyclosporin A treatment for immunosuppression after organ transplantation are predisposed to develop FAs.20,21,22 The tumors are typically bilateral and multiple. The duration of cyclosporin A treatment prior to the detection of a FA is generally more than a year, with a mean interval of 4.4 ± 1.7 years (range, 1.7 to 7.1 years) in one study.22 When compared with FAs found in control women who did not undergo transplantation or cyclosporin A treatment, cyclosporin A-related tumors were significantly larger and had a lower longitudinal to anterior-posterior ratio on imaging.22 Multiple

bilateral fibroepithelial lesions developed in a 15-year-old girl maintained for over a year on cyclosporin-based immunosuppressive treatment after liver transplantation for Wilson disease.23 The largest tumor was 8 cm in size and caused ulceration in the nipple-areolar region. The largest contralateral tumor measured 5 cm. Additional smaller tumor nodules were also present bilaterally. Histologically, the lesions were classified as low-grade (borderline) malignant PTs, but “little” mitotic activity was described, and there was “no apparent heteromorphism of the nuclei,” leading the authors to acknowledge difficulty in distinguishing the lesions from FAs. The representative histologic images of this case are highly suggestive of juvenile FA. Iaria et al.24 reported complete regression of 8/21 FAs in eight renal transplant patients after “cyclosporine” was replaced with “tacrolimus,” another immunosuppressive drug. The other FAs remained stable or decreased in size at a mean follow-up of 41.8 months (range 25 to 57). It is unclear whether Epstein-Barr virus is25 or is not26 associated with the FAs that develop in immunocompromised patients.

bilateral fibroepithelial lesions developed in a 15-year-old girl maintained for over a year on cyclosporin-based immunosuppressive treatment after liver transplantation for Wilson disease.23 The largest tumor was 8 cm in size and caused ulceration in the nipple-areolar region. The largest contralateral tumor measured 5 cm. Additional smaller tumor nodules were also present bilaterally. Histologically, the lesions were classified as low-grade (borderline) malignant PTs, but “little” mitotic activity was described, and there was “no apparent heteromorphism of the nuclei,” leading the authors to acknowledge difficulty in distinguishing the lesions from FAs. The representative histologic images of this case are highly suggestive of juvenile FA. Iaria et al.24 reported complete regression of 8/21 FAs in eight renal transplant patients after “cyclosporine” was replaced with “tacrolimus,” another immunosuppressive drug. The other FAs remained stable or decreased in size at a mean follow-up of 41.8 months (range 25 to 57). It is unclear whether Epstein-Barr virus is25 or is not26 associated with the FAs that develop in immunocompromised patients.

Clinical Presentation

Age and Hormonal Status

The age distribution for FAs ranges from childhood to more than 70 years of age, with a mean age of about 30 years and a median of about 25 years.27 Less than 5% of women with a FA as their presenting tumor are older than 50 years or are postmenopausal. In a series of 709 consecutive breast biopsies, FA constituted 14% of all lesions, and 44% occurred in postmenopausal women.28 FAs accounted for 20% of benign masses and 12% of all masses in postmenopausal patients. A study of FAs from premenopausal women found no difference in mitotic index or nuclear volume in FAs obtained in the luteal and secretory menstrual phases.29 The authors concluded that fibroadenomatous epithelium is independent of the cyclic action of circulating hormones and influenced mainly by paracrine factors. Rego et al.30 correlated the epithelial changes in FAs with menstrual date reported by the patient and with serum progesterone levels on the day of surgical biopsy. This study found no significant variation in Ki67 indexes in the epithelium of FA in the follicular phase (27.88 ± 27.52 positive nuclei per 1,000 cells) and in the luteal phase (37.88 ± 31.08 positive nuclei per 1,000 cells). The authors concluded that the absence of cyclical proliferative fluctuations in the epithelium of FAs suggests that it represents a neoplasm. Others, however, have observed focal cytologic alterations in the epithelium of FAs compatible with hormonal effect, including secretory changes.31,32,33

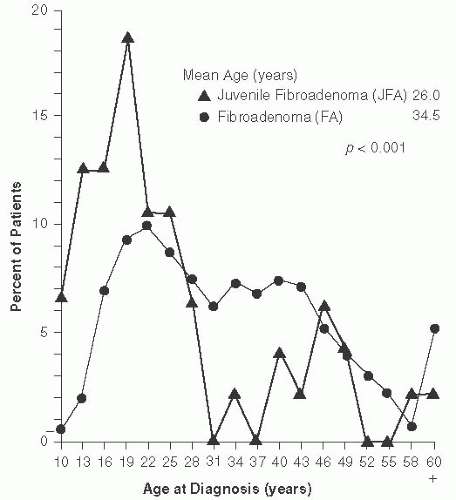

Patients with juvenile FAs tend to be younger than the average age for adult FAs, with the majority younger than 20 years of age34,35,36 (Fig. 8.2). Juvenile FAs constituted 45% of the tumors in a series of 47 consecutive fibroepithelial lesions in children and adolescent women (age less than 18 years),36 but tumors with the histologic features of juvenile FA have been found in adult women as old as 72 years.37 Juvenile FAs can also occur at a very young age. A 3-cm tumor morphologically consistent with juvenile FA has been described in a 16-month-old girl.38

Patients with complex FA tend to be older than women with noncomplex FAs. Kuijper et al.39 reported a mean age of 34.5 years. In the series by Sklair-Levy et al.,40 the median age of patients with complex FA (47 years; range 21 to 69) was significantly higher than the median age of patients with noncomplex FAs (28.5 years; range 12 to 86) (p < 0.001).

Clinical Symptoms

In most cases, the presenting symptom is a painless, firm or rubbery, well-circumscribed, solitary mass found by the patient. An increasing percentage of FAs are nonpalpable tumors detected by mammography. The left breast is affected slightly more often than the right, and the single most frequent location is the upper outer quadrant.27 Multiple FAs occur in about 15% of patients, with equal proportions detected synchronously and metachronously in the same or opposite breast. Foster et al.27 found that 36% of metachronous FAs developed in the same quadrant as the first FA after a mean interval of about 4 years. FAs can arise in supernumerary breast tissue on the chest wall33 or in the vulva,33,41,42 as well as in axillary breast tissue, where they can clinically mimic neoplastic lymphadenopathy.

Most patients with a juvenile FA present with a single, painless, discrete mass that may grow rapidly36 and sometimes becomes large enough to cause marked asymmetry.

In one study consisting of only African American women ranging in age from 10 to 39 years old, 8 patients had more than one lesion, and 13 had a solitary tumor.34 The age distribution and median age of individuals with single and multiple tumors were similar at the time of first operation. The frequency of recurrences decreases in early adulthood, and lesions that are not excised may stop growing in adulthood, remaining stable even during pregnancy.35

In one study consisting of only African American women ranging in age from 10 to 39 years old, 8 patients had more than one lesion, and 13 had a solitary tumor.34 The age distribution and median age of individuals with single and multiple tumors were similar at the time of first operation. The frequency of recurrences decreases in early adulthood, and lesions that are not excised may stop growing in adulthood, remaining stable even during pregnancy.35

Another uncommon syndrome occurring in adolescence is the metachronous and synchronous development of multiple FAs, usually in both breasts. This condition occurs more often in adolescent African-American girls than in White or Asian girls.43 Despite repeated excision, new tumors are formed, probably because the breast tissue exhibits diffuse fibroadenomatoid hyperplasia. The familial occurrence of multiple successive FAs has been observed.

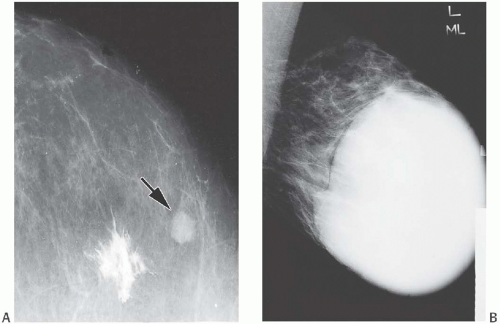

Radiology

FAs and cysts may be indistinguishable on palpation and also by mammography (Fig. 8.3). Large and coarse calcifications are not uncommon in FAs after menopause. Most FAs have ultrasound features of a benign tumor. Fleury et al.44 reported that they could separate usual FAs from complex and hypercellular FAs using sonoelastography. Adamietz et al.45 reported that sonoelastography could help differentiate FA from PT. All PTs in their study showed an elastic center surrounded by inelastic peripheral tissue (also referred to as “ring sign”), while this pattern was present in only 5% of FAs. These observations need to be validated in larger series. A minority of FAs, including lactating adenomas, have irregular margins, a heterogeneous appearance, and posterior shadowing on ultrasonography, which may suggest a malignant tumor.46 Yamaguchi et al.47 reported that FAs with myxoid changes show significantly greater depth-to-width ratio than usual FAs when examined by sonography. In their series, 16/17 lesions sonographically suspicious for mucinous carcinoma due to rapid growth, large size, high depth-to-width ratio, round shape, and internal hyperechogenicity were found to be myxoid FAs at the time of surgical excision.

FIG. 8.3. Fibroadenoma. A: The nonpalpable tumor was detected as a homogeneous, oval, circumscribed mass on this mammogram (arrow). The stellate white focus is the site of dye injected for localization of the lesion at surgery. B: This FA nearly fills the right breast of an 18-year-old girl in a medial-lateral view. |

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of FAs is variable and influenced by the structure and relative proportions of epithelial and stromal components.48,49 Wurdinger et al.50 studied 81 FAs using MRI and found that 70.4% had well-defined margins, 90.1% were round or lobulated, 49.4% had heterogeneous internal structure, and 27.2%

displayed nonenhancing internal septations. After contrast injection, 22.2% of FAs had a suspicious signal intensity-time course.18F-FDG uptake can occur in a FA undergoing rapid growth and proliferation. A “juvenile FA” positive on111In-octreotide scan and18F-FDG-positron emission tomogram/computerized tomogram has been described in a 14-year-old girl with an abdominal neuroendocrine tumor. The histology of the breast tumor was not reported.51

displayed nonenhancing internal septations. After contrast injection, 22.2% of FAs had a suspicious signal intensity-time course.18F-FDG uptake can occur in a FA undergoing rapid growth and proliferation. A “juvenile FA” positive on111In-octreotide scan and18F-FDG-positron emission tomogram/computerized tomogram has been described in a 14-year-old girl with an abdominal neuroendocrine tumor. The histology of the breast tumor was not reported.51

Size

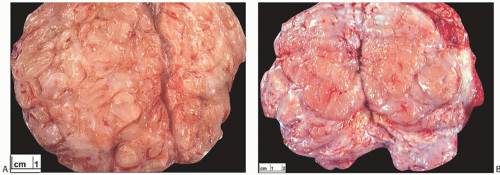

Most FAs are not larger than 3 cm (Fig. 8.4). In one series, only 10% of the tumors were larger than 4 cm.27 FAs larger than 4 cm are significantly more frequent in patients 20 years or younger than in older patients.27 An occasional tumor may grow to involve most or the entire breast. These tumors, often referred to as adolescent or giant FAs, develop as solitary or multiple masses shortly after puberty43,52 (Fig. 8.5). One or both breasts can be affected.

In one series, the mean sizes of solitary and multiple juvenile FAs were 2.8 and 2.2 cm, respectively, with the largest tumor measuring 13 cm in a patient with multiple lesions. Others have reported solitary tumors up to 22 cm in diameter.35

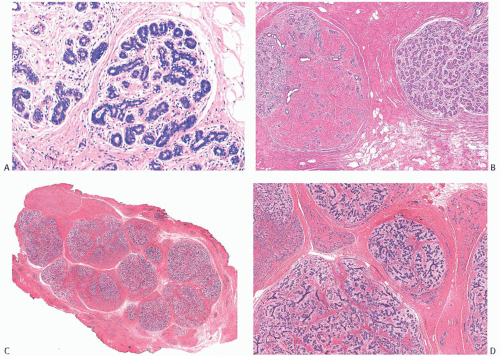

FIG. 8.4. Fibroadenomas. A: Relatively homogenous cut surface. B: Multiple cysts are present. C: Two adjacent FAs, the larger of which, above, is solid in contrast to the smaller, centrally placed, partly cystic tumor. D: Gross appearance of FA in which there are patches of adipose tissue. |

Sklair-Levy et al.40 reported that the average size of complex FAs (1.3 ± 0.57 cm; range 0.5 to 2.6) was about half that of usual FAs (2.5 ± 1.44 cm; range 21 to 69) (p < 0.001).

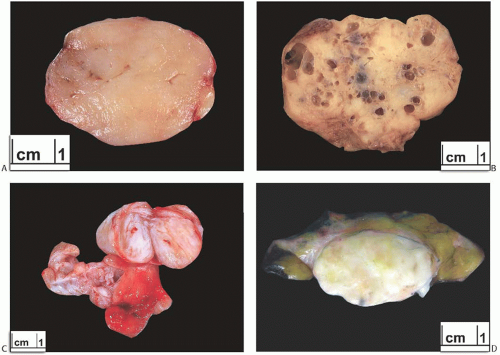

Gross Pathology

FAs are often excised by using blunt dissection to peel away the surrounding tissue. The outer surface of a “shelled out” FA has a smooth, bosselated contour. The cut surface of the bisected tumor is composed of bulging, firm, and gray, white, or tan tissue (Fig. 8.4). A minority of FAs have a myxoid or gelatinous appearance. Some tumors appear to be composed of multiple aggregated nodules divided by septa. Extremely rare FAs contain a lipomatous component (fibroadenolipoma) (Fig. 8.4).

On gross examination with a magnifying glass, very fine clefts in the tissue can be identified in the cut surface of some tumors, but these clefts are infrequently pronounced. Discrete round cysts are sometimes present, measuring

1 mm to 1 cm or more in diameter, and rarely the tumor is so cystic that it grossly resembles a cystic papilloma (Figs. 8.4 and 8.6).

1 mm to 1 cm or more in diameter, and rarely the tumor is so cystic that it grossly resembles a cystic papilloma (Figs. 8.4 and 8.6).

Juvenile FAs are grossly indistinguishable from the adult variety of the tumor.34

Microscopic Pathology

The origin of a FA from the TDLU was elegantly demonstrated by Demetrakopoulos53 using a serial-section reconstruction technique. The stroma was found to cause numerous invaginations in the walls of branches of the duct within the tumor corresponding to the intracanalicular pattern seen in histologic sections. The significance of specialized stroma in the growth of FAs has been emphasized by Koerner and O’Connell,54 who suggested that a FA is a hyperplastic lesion of the specialized (intralobular) mammary stroma, and that the growing glandular structures are secondarily distorted by the stromal proliferation. These observations confirm the long-held view that FAs are formed as a result of proliferation of stroma around the terminal duct and within the lobule.55

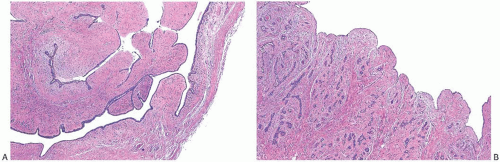

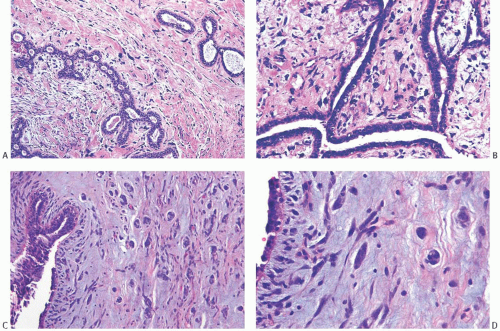

The histologic hallmark of all FAs is concurrent proliferation of glandular and stromal elements. The growth pattern has been referred to as either intracanalicular or pericanalicular. The intracanalicular pattern is produced when the stroma is sufficiently abundant to compress ducts into elongated linear branching structures with slit-like lumens (Fig. 8.7A,B). When the ducts are separated by expanded stroma but they retain the original round profile, the architecture has a pericanalicular pattern (Fig. 8.7C,D). These structural features have no prognostic or clinical significance, and many tumors have both components. FAs with a prominent intracanalicular pattern may be mistaken for benign PTs, especially in needle core biopsy samples.

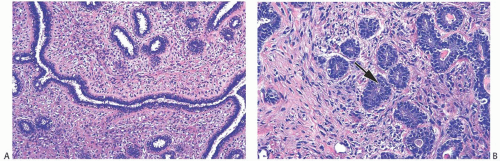

FIG. 8.7. Intracanalicular and pericanalicular patterns. A,B: When the lesional stroma stretches the lobular units and ducts into elongated tubular structures and compresses the glandular lumen, the pattern is referred to as intracanalicular. It commonly occurs in usual (adult-type) FAs, as depicted in this example. C,D: When the lesional stroma is expanded but does not bulge into the glandular lumen, and the latter maintains a round outline, the growth pattern is described as pericanalicular. These examples are from an adult-type FA (C) and a juvenile FA (D). |

Several terms have been used to subclassify FAs. More than 90% of FAs are of the adult/usual type, with the remainder fulfilling criteria for a diagnosis of juvenile FA or other unusual variants of FA. Large or giant FAs are histologically indistinguishable from their counterparts of average size. Tumors described by this term have included benign PT and hamartoma, and the designation of giant FA is best reserved to indicate the clinical presentation rather than a specific pathologic diagnosis.

The appearance of the stroma varies from one FA to another, but it is usually homogeneous in any given lesion. This is an important distinction from PTs that can exhibit considerable stromal heterogeneity, including regions indistinguishable from a FA.

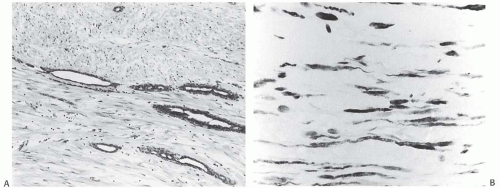

Uncommon forms of stromal differentiation are encountered in a minority of FAs. These include smooth muscle (myoid) metaplasia56 (Fig. 8.8) and adipose differentiation. Most fibroepithelial tumors with adipose differentiation are PTs.57 Osteochondroid metaplasia in a FA is very uncommon, and it almost always occurs in postmenopausal women.58,59

Giant cells, sometimes with multiple nuclei, are found in the stroma of FAs60,61 as well as in PTs61 and other benign breast tumors.62 The nuclei of multinucleated stromal giant cells may be pleomorphic and hyperchromatic (Fig. 8.9). In some tumors, these cells display a florette-like pattern. In a case studied by the Senior Editor, the giant cells were reactive for CD68, a histiocytic marker, and only a minority of these cells were immunoreactive for actin or CD34. In two FAs with multinucleated stromal cells studied by Ryska et al.,62 the multinucleated cells were positive for vimentin and CD34; in one case, the cells were also p53 positive. These multinucleated cells have ultrastructural features consistent with fibroblasts. A FA with the multinucleated giant cells has been described in a patient with Li-Fraumeni syndrome.63 The multinucleated stromal cells in a breast FA from a woman recovering from chicken pox contained ultrastructural evidence of cytoplasmic viral particles.64 Huo and Gilcrease65 reported four cases of FA-like lesions with pleomorphic giant cells and focal stromal hypercellularity. One of the four lesions measured 10 cm in

size. It had focally hypercellular stroma, and possibly represented a benign PT. A FA from a patient treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast carcinoma also showed focal stromal pleomorphism. Clinical follow-up information for three of these patients ranged from 16 to 59 months and was benign in all cases. Despite their atypical cytologic appearance, the presence of multinucleated stromal cells does not appear to influence the clinical course of the lesion. A tumor with the structural features of a FA should not be classified as a PT because the stroma contains multinucleated stromal giant cells.

size. It had focally hypercellular stroma, and possibly represented a benign PT. A FA from a patient treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast carcinoma also showed focal stromal pleomorphism. Clinical follow-up information for three of these patients ranged from 16 to 59 months and was benign in all cases. Despite their atypical cytologic appearance, the presence of multinucleated stromal cells does not appear to influence the clinical course of the lesion. A tumor with the structural features of a FA should not be classified as a PT because the stroma contains multinucleated stromal giant cells.

FIG. 8.8. Myoid stroma in fibroadenoma. A: Attenuated ductal structures among bundles of myoid stromal cells. B: Immunoreactivity for actin in the stroma detected with the HHF35 antibody. |

FIG. 8.9. Fibroadenoma with stromal giant cells. A: Cells with hyperchromatic nuclei are present in PASH in a FA. B: Multinucleated stromal giant cells in another tumor. C,D: Multinucleated stromal cells in a needle core biopsy specimen. The elongated spindle cells in (D) simulate invasive carcinoma, but were negative for CK AE1:3 (not shown). |

Two case reports of lesions showing overlapping features of FA and papilloma66,67 have raised the possibility of a related pathogenesis.

Usual (Adult-Type) FA

The majority of FAs are of adult type. In the average adult FA, the relative proportions of epithelium and stroma are evenly balanced throughout the tumor (Fig. 8.7A), and the density of the stromal cellularity is not related to tumor size. However, FAs from women younger than 20 years of age tend to have more cellular stroma and more proliferative epithelium as a group than do tumors from older women.36,68 Mitotic figures are extremely unusual in fibroadenomatous stroma. Sparse mitotic activity may be observed in FAs in adolescent girls.36 Elastic tissue is virtually absent from the stroma of adult FAs. In most instances, the microscopic diagnosis of adult FA is accomplished without difficulty when the tumor has a sharply defined border and the pericanalicular or intracanalicular growth pattern. However, the distinction between FA with cellular stroma and benign PT is sometimes problematic. In these situations, it may be helpful to review the characteristic cytologic features of FAs in formulating the diagnosis. Unfortunately, neoplasms that ultimately recur with the histologic and clinical features of a PT may occasionally present in a form that is histologically indistinguishable from a FA.

FIG. 8.10. Fibroadenoma with myxoid stroma. A: Myxoid FA has a sharp border with the surrounding breast parenchyma, as shown in this case. This tumor may sometimes raise the differential diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma. B: A duct is distended and compressed by the hypocellular myxoid stroma. C,D: A myxoid FA with SA. |

The stroma of FA in postmenopausal women tends to be hypocellular and hyalinized, and it often harbors coarse dystrophic calcifications.

Myxoid FA

The stroma of FAs can undergo marked myxoid change (Fig. 8.10). Specimens from such lesions examined by frozen

section, by imprint cytology, by fine-needle aspiration (FNA), or by needle core biopsy may be mistaken for mucinous carcinoma. Myxoid FA and myxomatous stromal masses have been encountered in the familial condition of cutaneous and cardiac myxomas, spotty cutaneous pigmentation, endocrine overactivity, and melanotic schwannomas referred to as Carney syndrome.12 However, most patients with a myxoid FA do not have a known systemic abnormality.

section, by imprint cytology, by fine-needle aspiration (FNA), or by needle core biopsy may be mistaken for mucinous carcinoma. Myxoid FA and myxomatous stromal masses have been encountered in the familial condition of cutaneous and cardiac myxomas, spotty cutaneous pigmentation, endocrine overactivity, and melanotic schwannomas referred to as Carney syndrome.12 However, most patients with a myxoid FA do not have a known systemic abnormality.

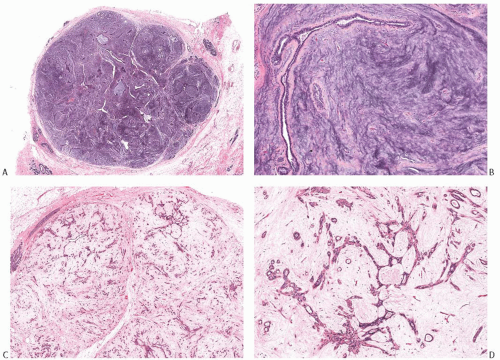

Complex FA

FAs with sclerosing adenosis (SA), papillary apocrine hyperplasia, cysts, or epithelial calcifications have been designated “complex”69 (Fig. 8.11). At least one of these histologic features must be present for the lesion to be classified as complex FA. Foci of florid adenosis can also be encountered. Complex FAs constituted 22.7% of 2,458 FAs in one series.69 A review of 396 FAs from a single institution revealed “complex histologic features” in 40.4% of the tumors.39 In a series of 63 complex FAs studied by Sklair-Levy et al.,40 SA was present in 57% of cases, apocrine metaplasia in 8%, and cysts in 1.6%. Calcifications were associated with SA in 9.5% of the cases. Excessive FCCs, especially papillary epithelial hyperplasia and SA, can mask the basic fibroadenomatous nature of a tumor, especially in the limited sample of a needle core biopsy specimen (Fig. 8.11B).

FIG. 8.11. Complex fibroadenoma (A,B) and complex fibroadenoma with sclerosing adenosis (C,D). A: Whole-mount histologic section showing cysts and dark irregular foci of SA. Parts of this complex FA appear papillary. B: Excessive FCCs can mask the basic fibroadenomatous nature of the lesion in a limited sample obtained by needle core biopsy. C: The fibroadenomatous nature of the lesion is manifested by the elongated ducts. D: This example shows extensive sclerotic membrane formation around the glands. |

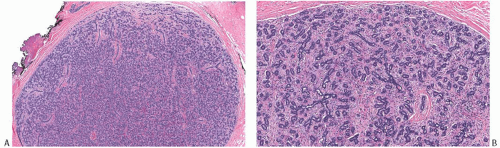

Juvenile FA

Juvenile FAs account for about 4% of all FAs.34 They are characterized microscopically by stromal cellularity and epithelial hyperplasia (Fig. 8.12). The architecture is more often pericanalicular than intracanalicular, or there is a mixture of these patterns. No appreciable overall differences are found between tumors in patients with solitary and multiple lesions.35 However, there may be heterogeneity

in the histologic appearance of different tumors from an individual with multiple lesions. The tumor border is usually well defined microscopically, sometimes by a pseudocapsule of compressed parenchyma (Fig. 8.12). Secondary peripheral nodules of fibroadenomatous growth outside the main tumor are encountered in a minority of cases, usually in patients who develop multiple tumors. Mitoses are rarely detected in the stroma of juvenile FAs in adults, but stromal mitoses can be substantial in lesions from adolescents.36 Little or no atypia and pleomorphism are encountered in the bipolar stromal cells (Figs. 8.12 and 8.13). Ross et al.36 studied 23 juvenile FAs in women 18 years old or younger. The tumor mean size was 3.1 cm (range, 0.5 to 7). All lesions had circumscribed, noninfiltrative borders and showed pericanalicular growth pattern. The stroma was uniformly cellular, with no separation between intralobular/periglandular stroma and interlobular stroma.

in the histologic appearance of different tumors from an individual with multiple lesions. The tumor border is usually well defined microscopically, sometimes by a pseudocapsule of compressed parenchyma (Fig. 8.12). Secondary peripheral nodules of fibroadenomatous growth outside the main tumor are encountered in a minority of cases, usually in patients who develop multiple tumors. Mitoses are rarely detected in the stroma of juvenile FAs in adults, but stromal mitoses can be substantial in lesions from adolescents.36 Little or no atypia and pleomorphism are encountered in the bipolar stromal cells (Figs. 8.12 and 8.13). Ross et al.36 studied 23 juvenile FAs in women 18 years old or younger. The tumor mean size was 3.1 cm (range, 0.5 to 7). All lesions had circumscribed, noninfiltrative borders and showed pericanalicular growth pattern. The stroma was uniformly cellular, with no separation between intralobular/periglandular stroma and interlobular stroma.

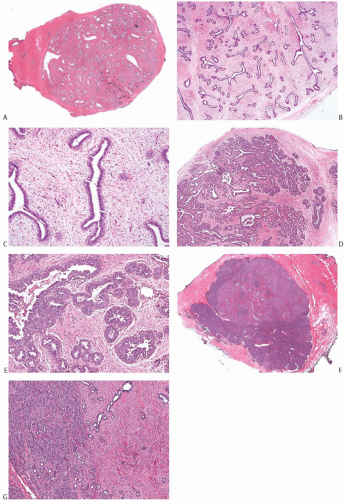

FIG. 8.12. Juvenile fibroadenoma. A: Whole-mount histologic section of a juvenile FA. B,C: The lesion has a circumscribed border and the typical architecture of a FA with the pericanalicular pattern. D,E: This tumor shows the typical fibroadenomatous architecture, with extensive epithelial component. The epithelium is hyperplastic. F,G: This unusual tumor from a 16-year-old girl consists of a fibroadenomatous area coexisting with tubular adenoma. The two components are best appreciated in (G). |

FIG. 8.13. Juvenile fibroadenoma. A: The stroma is moderately cellular with a slight tendency to condensation around epithelial structures. B: Mitotic activity is present in the epithelium (arrow). |

Epithelial elements in a juvenile FA are usually distributed homogeneously. It is exceptional to find a 40× microscopic field occupied entirely by stroma. Ross et al.36 encountered a few tumors with foci of slight stromal expansion adjacent to gland-rich areas, creating an overall impression of intratumoral heterogeneity that could lead to a diagnosis of PT. In such cases, the uniform quality of the stromal proliferation and lack of nuclear atypia are features critical to reaching the correct diagnosis. Most juvenile FAs feature conspicuous epithelial hyperplasia (see section on epithelium in FA).

Tubular Adenoma

The so-called tubular adenoma70 or pure adenoma71 is a variant of pericanalicular FA with an exceptionally prominent or florid adenosis-like epithelial proliferation (Fig. 8.14). The clinical presentation as a mobile, circumscribed painless mass is indistinguishable from that of an adult FA. These tumors are not associated with pregnancy or oral contraceptive use.72 They tend to be softer than the average FA, and tan rather than white. Microscopic examination reveals closely approximated round or oval glandular structures composed of a single layer of epithelium supported by a layer of myoepithelial cells. A small amount of secretion is frequently

present in the glandular lumens, even in tumors from patients who are not pregnant or taking oral contraceptives.33 This secretion is not immunoreactive for α-lactalbumin.73

present in the glandular lumens, even in tumors from patients who are not pregnant or taking oral contraceptives.33 This secretion is not immunoreactive for α-lactalbumin.73

Other Types of Adenoma

Other so-called adenomas are unrelated to the FA category. Apocrine adenoma is a localized nodular focus of prominent papillary and cystic apocrine metaplasia.74,75 Nodular foci of SA with apocrine metaplasia have been variously termed apocrine adenoma and apocrine adenosis. Ductal adenoma76,77 and pleomorphic adenoma78,79,80 are variants of intraductal papilloma (discussed in Chapter 5) or adenomyoepithelioma (discussed in Chapter 6).

Infarction in a FA

FAs and lactating adenomas are prone to develop foci of infarction during pregnancy,81 but infarction has been found in tumors removed from patients who were neither pregnant nor lactating.82,83,84 Clinically, the infarcted tumor may be tender or painful. The recent onset of discomfort in a previously painless tumor is suggestive of infarction in a FA.82,83 The infarcted area can be appreciated grossly as a relatively well-demarcated, pale yellow or white zone of coagulation necrosis. Microscopic examination of the necrotic region reveals the ghostly outline of the underlying structure of the FA in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections (Fig. 8.15). The architecture of the tissue can be seen to better advantage with a reticulin stain82 and, if the tissue is not too degenerated, with cytokeratin (CK) stains, AE1:3 in particular. Thrombosed vessels have been detected in some lesions.83

Epithelium in FA

The epithelial component of FAs is prone to various alterations. These include foci of minimal epithelial hyperplasia, apocrine metaplasia and squamous metaplasia,85 cyst formation, and the spectrum of proliferation termed FCC, including apocrine metaplasia, which characterizes complex FA.

Marked epithelial hyperplasia can be encountered in a complex FA or in the absence of a background of FCCs. Generally, these proliferative foci have the same features as hyperplastic lesions outside a FA. Although once attributed to oral contraceptive use,86 it has been shown that these epithelial changes occur independent of exogenous hormones.87,88 Secretory hyperplasia sometimes occurs diffusely in FAs during pregnancy,33 or a preexisting FA

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree