Chapter 10. Specialty acute presentations

Rheumatological 283

Dermatological 292

Ear, nose and throat 308

Ophthalmic 313

Obstetric 318

Gynaecological 331

Paediatric 335

Surgical lumps 343

HAEMATOLOGICAL

Presentation

Symptoms attributable to a blood disorder are non-specific and wide-ranging. Anaemia may be associated with fatigue, breathlessness and worsening of existing cardiovascular diseases resulting in angina, claudication, syncope or palpitations. Spontaneous bleeding or haemarthrosis may indicate a coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia. Infection may reflect an underlying white blood cell dyscrasia. In addition, systemic symptoms such as weight loss, sweats and a fever are associated with a variety of blood disorders (see ‘Leukaemia and lymphoma’, p. 370 and p. 373). Therefore, the diagnosis of these conditions requires a high index of suspicion and is often based on blood test abnormalities. Clinical signs may be subtle or absent and are not limited to one system. Abnormalities may include:

• eyes: conjunctival pallor, yellow sclera indicating jaundice, fundal haemorrhage

• mouth: angular stomatitis, telangiectasia, smooth tongue, mucosa petechiae, tonsillar enlargement, gum hypertrophy

• hands: koilonychia, telangiectasia

• cardiorespiratory: tachycardia or signs of heart failure

• neck and axilla: nodal enlargement and, if present, site, tenderness, mobility, character (soft, rubbery)

• abdomen: splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, nodes, ascites

• joints and feet: limited movement or swelling, impaired peripheral circulation

• urine: for blood or urobilinogen.

Red blood cell disorders

These are classified based on the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of the red cell population. Microcytic anaemias are characterized by low MCV (<76 fL); macro-cytic anaemias are characterized by a high MCV (>100 fL). Remember that the MCV is an average and if there is a bimodal distribution of red cell volumes (e.g. a microcytic anaemia due to chronic bleeding in combination with a reticulocytosis due to a more acute haemorrhage) the MCV can be misleading. If in doubt, ask haematology to examine a blood film.

Microcytic and normocytic anaemias

Causes include:

• iron deficiency: this is most common and is associated with red cell hypochromia

• bleeding or haemolysis: may be associated with a reticulocytosis

• thalassaemia: target cells with basophilic stippling on the blood film and haemolysis; see below

• sideroblastic anaemia: dimorphic cells on the blood film

• anaemia of chronic disease: this may result from malignancy, chronic infection or inflammation; it may also result in normochromic, normocytic anaemia.

Iron deficiency

Gastrointestinal loss, menstrual blood loss and pregnancy are the most common causes. Malabsorption (e.g. due to hypochlorhydria or coeliac disease) should also be considered. Serum ferritin is a helpful indicator of low iron stores; however it can also be low in hypothyroidism and may be elevated as part of the acute phase response. In such situations, a transferrin or total iron binding capacity should be checked.

Further investigation should focus on the suspected aetiology, e.g. endoscopy for gastrointestinal blood loss, serum antigliadin antibodies or TTG ± duodenal biopsy for coeliac disease, or stool examination for parasites.

Transfusion is rarely required, but should be considered where the anaemia exacerbates other diseases, e.g. IHD. Oral ferrous sulphate (200 mg 8-hourly) for 3–6 months is usually sufficient if a cause can be identified and treated. Otherwise indefinite replacement may be required. Ferrous gluconate (300 mg 12-hourly PO) can be used if patients are intolerant of ferrous sulphate.

Thalassaemia

This group of inherited conditions is characterized by underproduction of the globin chains within the haemoglobin molecule. There are several genetic abnormalities which affect the production of α and β chains, resulting in α and β thalassaemia, respectively. Homozygotes for these mutations develop thalassaemia major, while heterozygotes develop thalassaemia minor (also known as thalassaemia trait).

β-Thalassaemia is the most common and is found predominantly in Mediterranean populations. In the minor variety, there is only mild hypochromic anaemia with punctuate basophilia and target cells. However, the major form results in an inability to make HbA and severe hypochromic anaemia from the first few months of life, with erythroblastosis and raised levels of fetal haemoglobin (HbF). Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation is an effective treatment, if a donor can be found. Otherwise, repeated transfusion (with desferrioxamine to reduce iron overload), bone marrow support with folic acid 5 mg daily, and splenectomy are alternatives. Screening of a potentially affected fetus should be considered.

α-Thalassaemia is most common in South-East Asian communities. α-Thalassaemia major can cause hydrops fetalis and fetal death. Patients with less severe forms of the disease have a higher survival rate, but often need support similar to that for β-thalassaemia.

Macrocytic anaemias

Causes include:

• vitamin B 12 deficiency

• folate deficiency

• alcohol

• hypothyroidism

• artefact, commonly caused by reticulocytosis, e.g. in haemolysis or active bleeding.

Vitamin B 12 deficiency

Neurological sequelae, due to demyelination, can result from significant B 12 deficiency and can occur in the absence of anaemia. Symptoms include paraesthesiae, numbness and, if left untreated, ataxia and subacute combined degeneration of the cord.

Pernicious anaemia

This results from autoantibody-mediated atrophy of the parietal cells of the gastric mucosa. These cells are responsible for the production of intrinsic factor (IF), which is necessary for B 12 absorption in the small intestine. PA may be associated with other autoimmune diseases. Anti-parietal cell antibodies are sensitive, but non-specific markers of PA; the presence of intrinsic factor antibodies is pathognomonic.

Schilling’s test can be used to distinguish pernicious anaemia from other causes of B 12 deficiency: This involves co-administration of 1 mg of oral and intramuscular radio-labelled vitamin B 12. The IM injection saturates body stores of B 12 and encourages renal excretion of the oral dose. A 24-h urine collection is then performed. Normal patients will excrete around 10% of the oral dose; excretion of <5% is considered abnormal. To differentiate between PA and other causes of B 12 malabsorption, B 12 dosing is repeated, this time with addition of oral intrinsic factor. PA is indicated by normalization of B 12 excretion on the second urine collection; a second abnormal result indicates a malabsorptive problem in the distal small intestine, e.g. coeliac or Crohn’s disease.

Treatment of PA involves administration of hydroxocobalamin (1000 μg IM in 5 doses over 2–3 days, followed by the same dose every 3 months indefinitely).

Folate deficiency

Causes include poor dietary intake (leafy vegetables, cereals, seeds), drugs that interfere with folate metabolism (e.g. methotrexate, phenytoin), malabsorption (e.g. due to coeliac disease), pregnancy and haemolysis.

Treatment is folic acid (5 mg PO daily for 3 weeks, then 5 mg weekly). B 12 levels must be checked before treatment is started. If these are not available, it is safer to assume and treat concomitant B 12 deficiency to avoid precipitating B 12-associated neuropathy.

Haemolytic anaemias

In health, a red cell circulates for 90–120 days before it is destroyed within the reticuloendothelial system. Accelerated red cell lysis leads to haemolytic anaemia; patients may present with typical symptoms of anaemia and jaundice is common, due a rise in unconjugated bilirubin. There are many causes of haemolytic anaemia, broadly grouped into hereditary and acquired conditions.

Hereditary haemolytic anaemias

These are not immune mediated; therefore the direct Coomb’s test will be negative. They are subclassified into:

• red cell membrane defects, e.g. hereditary spherocytosis and hereditary elliptocytosis

• enzyme deficiencies, e.g. glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), pyruvate kinase or pyrimidine 5′-nucleotidase

• haemoglobinopathies, e.g. sickle cell disease (see below) and thalassaemia (see above).

Hereditary spherocytosis

Commonly found in northern Europeans and Japanese and usually inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Defective production of cytoskeletal proteins results in large, spherical red cells which are visible on a blood film. These spherocytes are fragile, prone to haemolysis and are filtered by the spleen, resulting in anaemia. Patients may be asymptomatic or present with anaemia or complications related to haemolysis, e.g. pigment gallstones. The osmotic fragility test is positive.

Severe anaemia may result from infection (an aplastic crisis may be seen with parvovirus infection) or folate deficiency, e.g. during pregnancy. Management involves life-long folic acid prophylaxis (5 mg once weekly) ± splenectomy. Any transfusions must be given slowly. Families should be screened.

Hereditary elliptocytosis

May be autosomal dominant or recessive and is less common than hereditary spherocytosis in the UK. It usually causes an asymptomatic abnormality on the blood film. Occasionally results in neonatal haemolysis or a chronic compensated haemolytic state (managed as per hereditary spherocytosis).

G6PD deficiency

An X-linked recessive condition, this confers a malarial protective advantage to female heterozygotes, but is more severe when it affects Caucasians and Orientals. Infection and a range of drugs can precipitate haemolysis, as can ingestion of a form of broad bean (this is known as favism). Occasionally neonatal haemolysis can occur. Features include non-spherocytic intravascular haemolysis with ‘bite’ and blister cells on the blood film.

Pyruvate kinase deficiency

This is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait with varying degrees of anaemia. Characteristic ‘prickle cells’ like holly leaves are seen on the blood film.

Sickle cell disease

This results from a single glutamic acid to valine substitution at position 6 of the β-globin polypeptide chain. An autosomal recessive disease, it results in a preponderance of HbS and the fully expressed sickle cell phenotype only in homozygotes. Heterozygotes produce a mixture of HbA and HbS (termed AS), and express a far less severe, and often asymptomatic, phenotype described as sickle ‘trait’. Sickle trait confers resistance to falciparum malaria, hence the mutation has perpetuated in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest incidence of the condition.

Sickle cell anaemia produces abnormally shaped red cells that become stuck in small vessels. Because of its role as a filtration system for the bloodstream this leads to multi-infarct splenic injury and autosplenectomy, often by the end of childhood. Other serious complications include parvovirus B19 infection, which can lead to severe aplastic anaemia, and sickling crises, which may be precipitated by hypoxia, infection, hypothermia or dehydration. Examples of these include:

• bone vaso-occlusive crisis: affects small vessels in bones (often hands and feet in children, and long bones, ribs and vertebrae in adults); presents with acute severe bone pain ± fever or tachycardia

• sickle chest syndrome: commonest cause of death in adult sickle disease; ventilatory failure due to fat emboli following bone marrow infarction

• sequestration crisis: end-organ venous thrombotic occlusion with acute painful enlargement; often affects spleen or liver.

Patients require protection against infection with encapsulated organisms. They should receive regular pneumococcal vaccination, daily penicillin V prophylaxis and vaccination against Haemophilus and hepatitis B should be considered. Hydroxycarbamide may be beneficial and daily folic acid supplements should be given. A crisis will require analgesia, oxygen, fluids and antibiotic cover. In severe cases, exchange transfusion may be considered.

Acquired haemolytic anaemias

Acquired haemolytic anaemias are classified into immune-mediated causes (direct Coombs’ test is positive) and non-immune-mediated causes (direct Coombs’ test is negative).

• immune-mediated acquired haemolytic anaemias include autoimmune conditions (see below), allo-immune conditions, e.g. haemolytic disease of the newborn (see ‘Obstetric’, p. 318), and drug-induced haemolytic anaemia, most commonly due to methyldopa and high-dose penicillin

• non-immune-mediated acquired haemolytic anaemias may be due to the direct action of drugs on red blood cells (e.g. dapsone, sulfasalazine, arsenic); trauma (e.g. mechanical heart valves); infections (e.g. malaria, Clostridium perfringens); or microangiopathic haemolysis (e.g. in haemolytic uraemic syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and HELLP syndrome.)

Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

Red cell antibodies can be ‘warm agglutinins’, binding best at 37 °C, or ‘cold agglutinins’, binding best at 4 °C.

Warm agglutinin disease accounts for 80% of cases and is usually due to IgG antibodies. It is associated with haematological malignancy, other solid tumours, connective tissue disease, drugs (e.g. penicillin, quinine), inflammatory bowel disease and HIV infection. Haemolysis with spherocytes is seen on a blood film and the direct Coombs’ test is positive.

Management involves treatment of the underlying cause and oral steroids (1 mg/kg prednisolone). Splenectomy or immunosuppression may be necessary in refractory disease.

Cold agglutinin disease is usually due to complement-binding IgM antibodies. It is associated with low-grade B-cell lymphoma and infection, e.g. mycoplasma, glandular fever. Treatment includes keeping the extremities warm and oral steroids.

Polycythaemia

Polycythaemia can be relative (due to a reduction in circulating plasma volume) or genuine, due to increased red cell mass. Genuine polycythaemia may be:

• primary: due to the myeloproliferative disorder, polycythaemia rubra vera (PRV)

• secondary: to chronic hypoxia or increased erythropoietin secretion (most commonly from renal tumours).

Polycythaemia may present with pruritus (which is often worse after a hot bath), gout, angina and arterial thromboses. Treatment is of the underlying cause in secondary polycythaemia, although venesection may be required temporarily to reduce the risk of thrombotic complications. PRV is treated by venesection of approximately 500 mL blood every 7 days until the haematocrit is <0.45. Aspirin is used to limit the risk of thrombosis. Interferon or hydroxycarbamide is used as a myelosuppressant.

White blood cell disorders

Neutropenia

This is defined as a neutrophil count <1.5 × 10 9/L. Causes include cytotoxic drug therapy, infection, connective tissue disease, alcohol or bone marrow infiltration. Infection in neutropenic patients is poorly tolerated and can result in shock and rapid deterioration. Patients with neutropenic sepsis should be reviewed urgently and admitted for observation and treatment (see ‘Neutropenic sepsis’, p. 246).

Lymphopenia

Defined by a lymphocyte count <1 × 10 9/L. Associations include connective tissue disease, sarcoid, renal disease, lymphoma, drugs and severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome. Lymphopenia results in defective cell-mediated immunity and infection with viruses, fungi or TB.

Lymphocytosis

Due to infection, e.g. viral or whooping cough, or lymphoproliferative disease.

Eosinophilia

Due to allergic disorders, parasitic infection, drug hypersensitivity, connective tissue and skin diseases and malignancy.

Platelet disorders

Thrombocytopenia

May present with purpura, spontaneous bruising or haemorrhage. A bone marrow examination may be helpful to determine the cause, which will be due to either:

• reduced marrow production: marrow infiltration by tumour, leukaemia or myeloma; chronic alcohol excess; vitamin B 12 deficiency; drugs (e.g. thiazides); idiopathic

• excessive platelet consumption: DIC (see below), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (see below), viral infection, e.g. EBV, bacterial infection, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; splenomegaly; liver and connective tissue diseases.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

In children, ITP is often preceded by a viral infection, but in adults it is more commonly associated with connective tissue disease. Females are affected more often than men. Autoantibodies to platelet glycoprotein result in premature platelet consumption. This results in increased production of platelet precursors in the bone marrow (megakaryocytes).

In children, spontaneous bleeding and purpura are often self-limiting but steroids may be necessary. Severe cases require platelet transfusion and IV immunoglobulin. In adults, steroids are often less effective and IV IgG may be needed. Splenectomy is used for relapsing cases.

Thrombocytosis

This can be reactive (infection, chronic inflammation, malignancy, haemolytic anaemia or haemorrhage, trauma and tissue damage), due to myeloproliferation or primary megakaryocyte proliferation. Complications include stroke and other vascular events, or bleeding due to platelet dysfunction.

Pancytopenia

This term describes the combination of anaemia, leucopenia and thrombocyto-penia and may be due to:

• defective cell production due to bone marrow infiltration (e.g. by solid tumours, lymphoma, myeloproliferative disorders); hereditary or acquired aplasia, e.g. drug related or viral

• excess cell destruction (hypersplenism) is seen in myelofibrosis, portal hypertension and some infections, e.g. malaria.

Coagulation disorders

These are broadly divided into hereditary and acquired conditions.

Hereditary

Haemophilia

Haemophilia A

This is an X-linked inherited deficiency of factor VIII. Symptoms develop around 6 months of age and include spontaneous bleeding into joints and muscles and an increased bleeding tendency after trauma.

Factor VIII concentrate infusion is required for bleeding episodes and prior to surgery, and should be followed by a course of tranexamic acid. With repeated transfusion some patients may develop antibodies to factor VIII, rendering it ineffective. Activated clotting factors VIIa or FEIBA (factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activity) should be used instead.

Patients transfused before 1985 were exposed to an increased risk of transfusion-transmissible infections for which screening was not undertaken before this date. Thus, there is an increased incidence of hepatitis A, B, C, and HIV in haemophiliacs of this generation. Concerns persist regarding prion-related infections.

Haemophilia B

Also referred to as ‘Christmas disease’, this results from a reduction of factor IX and manifests much as haemophilia A, but is less common. Treatment is with factor IX concentrate.

Other clotting cascade deficiencies

Anti-thrombin deficiency

This is a protein that inactivates certain clotting factors. Deficiency produces a pro-thrombotic tendency. The condition is exacerbated by heparin.

Protein C+S deficiency

Protein C and S affect the inactivation of clotting cascade factors V and VIII. An inherited deficiency of either leads to a prothrombotic tendency.

Von Willebrand disease

Although common, this is usually mild. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder (chromosome 12), but individual expression can vary significantly. A protein deficiency occurs linked to the carriage of factor VIII and also the adherence of platelets to damaged tissue. Bruising, epistaxis and excess bleeding following trauma or surgery can result. Testing shows a low factor VIII level and a prolonged bleeding time. Desmopressin can temporarily raise the level of the protein involved. Severe episodes require transfusion of factor VIII concentrate.

Acquired

DIC

Endothelial damage from infections (e.g. Gram-negative or streptococcal), tumours or obstetric complications can trigger tissue factor expression, activation of the clotting cascade through the extrinsic pathway, and consumption of platelets, clotting factors and fibrinogen by intravascular coagulation. Blood tests show thrombocytopenia, a prolonged PT, APPT and a low fibrinogen. Treatment is that of the underlying cause and in particular of any associated infection, dehydration, acidosis or hypoxia. Platelet transfusion ± fresh frozen plasma may be necessary.

RHEUMATOLOGICAL

Rheumatological symptoms are a common reason for attendance at GP surgeries, A&E and a variety of hospital specialties. The most common acute presentations involve joint pain or stiffness and their causes, in adults and children, are detailed below.

Acute monoarthritis

The priority is to establish the diagnosis and commence appropriate therapy. The most important disorder to consider is septic arthritis; others include crystal arthritis, haemarthrosis, reactive arthritis or inflammatory monoarthritis. A careful history is important: ask about previous similar episodes, recent illnesses, medication, family history and a history of bleeding disorders or anticoagulation.

Clinical features

In septic arthritis, the history is usually short and is of pain in the affected joint for days rather than weeks. If examination reveals a hot swollen tender joint with restriction of movement, then urgent investigation is required.

Investigation

In a native joint, synovial fluid should be aspirated and the samples sent for polarizing microscopy, Gram-stain and culture before starting antibiotics; some microbiologists prefer the sample to be sent to the laboratory in blood culture bottles. If a prosthetic joint is affected, always refer to an orthopaedic surgeon.

Blood cultures should also be obtained and other relevant investigations include FBC, ESR, CRP and renal function. Plain radiology would not be expected to show any changes in an acute septic arthritis, but may point to an alternative diagnosis, e.g. chondrocalcinosis suggesting pseudogout. Ultrasound has a role in assisting joint aspiration in joints that are not easily accessible, such as the hip. In osteomyelitis, plain radiography may show bone destruction, but MRI is the best imaging modality. Deep bone biopsy may also be necessary.

Management

If septic arthritis is suspected IV empirical antibiotics should be commenced and the choice refined following investigation results. If the diagnosis is confirmed these should be continued for up to 2 weeks IV, followed by around 4 weeks of oral therapy. Flucloxacillin (2 g 6-hourly) ± gentamicin would be a normal first-choice regime. In the case of penicillin allergy, use either clindamycin (450–600 mg 6-hourly) or a 3rd generation cephalosporin, instead. However, alternative drugs may be necessary if there is a high risk of Gram-negative infection (2nd or 3rd generation cephalosporin, e.g. cefuroxime 1.5 g 8-hourly) or MRSA (vancomycin plus 2nd or 3rd generation cephalosporin).

In addition, a septic joint should be drained to dryness as soon as possible. Local protocols will determine whether this is by closed needle or by arthroscopy. Hip infection should involve early specialist advice from orthopaedics.

Osteomyelitis can be managed with similar antibiotics to that for septic arthritis (including fusidic acid), but a longer duration of IV treatment may be necessary. Surgical input is often required for drainage, debridement and bone stabilization and all cases should be managed in consultation with orthopaedics.

New-onset inflammatory polyarthritis

Clinical assessment

History

The following features are important discriminators and should be elicited from the history:

• duration of symptoms

• associated features, e.g. morning stiffness

• family history of RA or other arthritis

• personal or family history of associated conditions, e.g. psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease

• any recent history of sexually transmitted or diarrhoeal illness; uveitis or conjunctivitis; rash or fever; symptoms associated with a connective tissue disorder such as dry eyes, oral ulceration, photosensitive or other skin rash or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

The history may also include features suggestive of an alternative diagnosis. A history of limb girdle stiffness in a patient over the age of 50 may suggest polymyalgia rheumatica, whereas a very acute monoarthritis in a patient on diuretics may suggest gout. Also consider the possibility of rarer presentations, e.g. lymphoma, myeloma, sarcoid and vasculitis.

Examination

The pattern of joint involvement is an important factor. RA, for example, is charac teristically symmetrical, whereas psoriatic arthritis and other seronegative arthritides are frequently asymmetrical. RA is a polyarthritis with almost universal involvement of the hands or feet. A large-joint oligoarthritis or monoarthritis is uncommon in RA, but may occur in spondyloarthritis, reactive arthritis or gout. Predominant spinal involvement may suggest ankylosing spondylitis or another of the spondyloarthropathies. It is also helpful to record whether there is arthralgia alone or definite synovitis, e.g. a positive metacarpal or metatarsal squeeze test.

Investigation

While history and examination are the most important methods of determining if there is inflammatory arthritis, some investigations are helpful. These will usually be carried out in specialist centres and should not delay referral; see below.

• IgM rheumatoid factor is associated with poor prognosis (especially in high titre) and may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis

• antibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides (anti-CCP antibodies) have a high specificity for RA, are a reliable marker of persistent disease and, if available, are useful markers in early or undifferentiated arthritis

• ESR and CRP can be of value

• serological assays for organisms that cause a reactive arthropathy, where relevant

• plain radiology is seldom helpful in establishing a diagnosis in early disease

• ultrasound and MRI are more sensitive at detecting synovitis, but are best organized from the rheumatology clinic, where they will be used to direct management.

Management

Management of established rheumatoid arthritis

There is still controversy about how best to use disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Sequential monotherapy, ‘step-up’ and ‘step-down’ regimens are all still widely used. The British Society for Rheumatology website is a good source of up-to-date treatment guidelines.

The role of biological drugs is a rapidly changing field. At present in the UK, the use of anti-TNF drugs (infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab) is restricted to those who have failed conventional DMARD therapy. However, there is recent evidence to support their use in early disease and recommendations may change in the future as a result. Newer biological agents which have recently been licensed include rituximab, which is an anti-B cell antibody, and abatacept, which blocks T-cell co-stimulation. Other biological drugs are likely to become available in the future. While it is not possible to discuss individual treatment strategies in detail here, there are some general practice points which apply in the outpatient clinic.

Familiarize yourself with departmental policies regarding assessment and drug monitoring. Most rheumatology departments will have agreed shared-care policies with local GPs showing what monitoring is being carried out, by whom and how often. Many patients will also have a patient-held record of results.

There are now many well validated assessment tools that are being incorporated into routine clinical practice and used to guide changes in treatment. If a disease activity score (DAS) or other measure is usually recorded, find out what this means and what action should be taken.

Use the whole team, e.g. involvement of the specialist nurse, podiatrist, orthotist, physiotherapist and occupational therapist may be appropriate for a patient with foot pain and poor mobility.

Review drug therapy and discuss this with your consultant. In patients with active disease, escalate drug doses and consider combination or biological therapy. If the disease is well controlled consider reducing or stopping NSAIDs or steroids. Ask if the department has a protocol for stepping down DMARD therapy for patients in remission. Also consider intra-articular steroid for active joints. Ask for advice: rheumatology is a complex branch of medicine and expert input is valuable.

Low back pain

Low back pain is common with a lifetime prevalence of up to 70%. The important aspects of managing chronic low back pain include correctly diagnosing those patients with a specific cause for their pain, achieving pain relief and preventing disability.

About 90% of patients with low back pain will have ‘non-specific low back pain’. In the remaining 10% underlying causes can be found. These include vertebral fracture, ankylosing spondylitis, infection or malignancy. Features that suggest an underlying cause have been described as ‘red flags’ and include:

• onset <20 or >55 years

• non-mechanical or thoracic pain

• previous history of carcinoma, steroids or HIV

• feeling unwell, weight loss or widespread neurological symptoms

• structural spinal deformity.

Management

In acute low back pain, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and early mobilization are of value. Most acute low back pain will resolve within 1–2 weeks. Predictive factors for chronicity include a large number of personal, psychosocial and occupational factors. The most important of these include obesity, depression (especially when associated with somatization) and job dissatisfaction.

In patients with chronic low back pain, treatments employed include supervised exercise therapy with encouragement to remain active, analgesics, acupuncture, ‘back schools’ and cognitive behavioural therapy. In those with manual occupations, liaison with the employer to facilitate an early return to work on lighter duties may be appropriate.

Acute joint pain in children

Arthritis in children may present in different ways to adults. Musculoskeletal symptoms are common in childhood and only a small proportion of these will represent juvenile arthritis. Many children do not complain of joint pain and the clinical signs can be subtle. Some children will present with a limp or arm dysfunction. Restriction of range of movement at a joint is an important clinical sign. A subset of children will present with prominent systemic upset and constitutional features such as fever, lethargy, weight loss or irritability. It is important to ask about associated features, such as eye symptoms and rash.

Presentations

On the basis of the number of joints affected in the first 6 months of disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis is classified into six groups.

Oligoarthritis

This typically occurs in girls under 5 years of age. These children have a high frequency of anti-nuclear antibodies and chronic anterior uveitis which may be silent. For the majority the prognosis is good, although a significant minority have persistent disease.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis can affect boys or girls and the diagnosis requires a personal or family history of psoriasis. In some patients, the arthritis may precede the psoriasis.

Enthesitis

Enthesitis (inflammation at the insertion or either tendon or ligament) related arthritis most frequently affects older boys and shares some features with ankylosing spondylitis in adults. These children may present with a lower limb oligo- arthritis often associated with enthesitis at the plantar fascia or Achilles insertion. There may be a family history of ankylosing spondylitis or inflammatory bowel disease.

Polyarthritis

This is less common in children than in adults. A proportion of children with multiple joint involvement will have a symmetrical polyarthritis, associated with a positive rheumatoid factor, and a disease which clinically resembles rheumatoid arthritis in the adult. In younger children the disease is usually seronegative. Prognosis in polyarticular disease is poorer than in oligoarticular disease and persists, in a significant proportion, into adult life.

Other

Patients who fit no category or more than one category.

Limb girdle stiffness

Shoulder soft tissue injury (see ‘Shoulder injuries’, p. 266) and inflammatory arthritides may be responsible for limb girdle stiffness. However, an important condition to consider is polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR). Where PMR is present, a significant number of patients will also have giant cell arteritis (GCA) which is important to recognize because it can cause blindness.

Polymyalgia rheumatica

Presentation

This inflammatory disorder affects females more than males (3:1) and is diagnosed when three or more of the following criteria are present: age >65, ESR >40 mm/h, bilateral upper arm tenderness, morning stiffness of >1 h, onset of illness <2 weeks, depression and/or weight loss. The diagnosis is confirmed by a rapid clinical response to corticosteroids.

Polymyalgia rheumatica can present acutely with pain and stiffness or have an insidious onset where systemic symptoms predominate. A low-grade fever may be present.

Investigation and diagnosis

Blood tests commonly reveal a raised ESR; there may also be an elevated CRP, a normochromic, normocytic anaemia and a raised alkaline phosphatase. As the presentation of PMR may overlap with that of other conditions (myeloma, rheumatoid arthritis, connective tissue disease, myositis, fibromyalgia, osteomalacia), it is worth considering these in the investigation and including: protein electrophoresis, rheumatoid factor, autoantibodies, CK, calcium and phosphate.

Management

Treatment is with prednisolone (15 mg PO daily; reduced after 4 weeks to 10 mg daily). A dramatic response should be seen within 72 h. The daily dose is then reduced by 1 mg every 4–6 weeks over 6–12 months until it reaches 5 mg. Thereafter, the dose can usually be reduced by 1 mg every 3–4 months over 2 years. NSAIDs can also be used to help pain as the dose is reduced.

Relapses are common and respond to a temporary increase in the steroid dose before a slower further titrated reduction. If continued high doses are needed, or if corticosteroids cannot be withdrawn after 2 years, steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, should be considered.

Giant cell arteritis

Presentation

This inflammatory process usually affects females more than males (4:1) and those aged 70 or over. It is rare in the under 50s. It often affects the temporal artery and can cause headache, jaw claudication (suggested by pain on chewing), blurring of vision, scalp tenderness over the temporal artery and, if untreated, blindness. It can also be associated with systemic symptoms similar to those described in PMR and there is significant overlap between the two conditions; 50% of patients with giant cell arteritis will also have PMR and about 10% of those with PMR will have GCA. GCA may affect large arteries elsewhere and may result in aortic aneurysms or large artery thrombosis, e.g. CVA.

Investigation and diagnosis

Management

There is an immediate threat to the patient’s vision. Therefore, patients with GCA should be treated with high doses of steroids initially, e.g. prednisolone 40–50 mg daily with a slow reduction towards a 10 mg daily dose, over 6 weeks. Thereafter, doses should reduce by 1 mg/month, but a maintenance dose will be needed for at least a year. Relapses are managed with further dose increases and should prompt the consideration of steroid-sparing agents.

All patients requiring corticosteroids at over 7.5 mg/day for more than 3 months should have bone protection prescribed, e.g. bisphosphonates ± in women, hormone replacement therapy. Bone density should be measured by dual-energy X-ray densitometry (DEXA), ideally at the start of treatment. Likewise, gastric protection, e.g. omeprazole, should be considered.

Skin, muscle and systemic symptoms

Systemic symptoms may be caused by the inflammatory arthritides or their treatment. However, it is important to consider the possibility of other pathologies that may cause similar symptoms.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Epidemiology and aetiology

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the commonest of the multisystem connective tissue diseases (CTD). It affects 3/10 000 Caucasians and is more common in Afro-Caribbean races (20/10 000). About 90% of affected individuals are women. SLE results from the production of anti-nuclear antibodies; at least 50 different antigen targets have so far been identified.

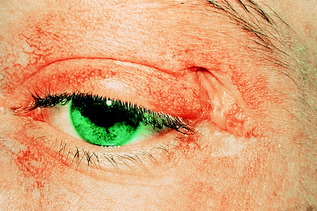

Presentation

SLE may present with any number of a wide range of clinical features. Of these, arthritis associated with Raynaud’s phenomenon is the most common. Mucocutaneous features include the classical butterfly facial rash (Fig. 10.1), discoid lupus and livedo reticularis (a feature of anti-phospholipid syndrome).

|

| Figure 10.1 Butterfly facial rash typical of SLE. |

A variety of joint symptoms may occur, including a small joint synovitis similar to RA. However, joint deformities are rare. There is an increased risk of venous thromboembolism and miscarriage due to production of anti-phospholipid antibodies (anti-phospholipid syndrome). Renal involvement (lupus nephritis) is heralded by haematuria, proteinuria and worsening renal impairment.

Diagnosis and investigation

Diagnosis requires recognition of typical symptoms and signs and demonstration of circulating anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA). Patients who are ANA-negative are unlikely to have SLE unless they are anti-Ro positive. Although antibodies to double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) are classically associated with SLE, these are present in only 30–50% of patients. The revised American Rheumatism Association criteria for the diagnosis of SLE require at least four of the 11 most common features of SLE for diagnosis (Table 10.1).

| Feature | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Malar (butterfly) rash | Fixed erythema, typical distribution, spares nasolabial folds |

| Discoid rash | Erythematous raised patches; adherent keratotic scar and follicular plugging |

| Photosensitivity | Rash in response to sunlight |

| Oral ulcers | Often painless |

| Arthritis | Involving two or more peripheral joints; non-erosive |

| Serositis | Pleuritis (effusion, rub or convincing story) or pericarditis (effusion, rub or ECG changes) |

| Renal | Persistent proteinuria >0.5 g/24 h or cellular casts on microscopy |

| Neurological | Seizures or psychosis in the absence of another cause |

| Haematological | Haemolytic anaemia or leucopenia/lymphopenia/thrombocytopenia, on two occasions, in the absence of another cause |

| Immunological | Anti-dsDNA in abnormal titre or antibodies to Sm antigen or positive anti-phospholipid antibodies |

| ANA disorder | Abnormal titre of ANA by immunofluorescence |

Management

All patients should avoid excessive sunlight and UV exposure and the use of high-factor sun blocks is essential. Patients with mild disease may only require intermittent analgesic or NSAIDs for joint symptoms. Oral hydroxychloroquine (200–400 mg daily) is often effective in controlling skin or more troublesome joint disease. Short courses of oral prednisolone (e.g. 40–60 mg daily) may be required for flairs of synovitis, pleuropericarditis or skin disease. The dose should be weaned oncecontrol is achieved and steroid-sparing agents may be useful, e.g. azathioprine, methotrexate. Life-threatening disease, such as cerebral, renal or pulmonary vasculitis, often requires pulsed IV methylprednisolone (0.5–1 g daily) and/or cyclophosphamide (0.375–1g/m 2 every 2–4 weeks). Patients with anti-phospholipid syndrome should receive life-long anticoagulation with warfarin after a first venous thromboembolic event.

Prognosis

The 5-year survival rate exceeds 90%. However, mortality in those who have had the disease for many years is higher, due to an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease, possibly reflecting long-term steroid use. Therefore, the lowest effective steroid dose should always be used. Poor prognostic features include development of lupus nephritis, pulmonary fibrosis (may be associated with ‘shrinking lung syndrome’) and pulmonary hypertension.

Systemic sclerosis

Presentation

Raynaud’s phenomenon is often the earliest clinical feature, usually followed by skin disease.

Skin disease is characterized by shiny, taut fingers with erythema and tortuous dilatation of capillary loops in the nail-fold bed. Classical facial features include thinning of the lips and radial furrowing around the mouth. Patients with skin involvement limited to distal sites (below knee and elbow, but excluding the face) are said to have limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (LCSS). Those with more extensive skin disease are described as having diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (DCSS). A proportion of patients with LCSS have the CREST phenotype (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, oesophageal involvement, sclerodactyly and telangiectasia) (Fig. 10.2).

|

| Figure 10.2 Typical facial appearance in CREST syndrome. |

Arthralgia is common, but functional limitation of the hands is due to skin thickening rather than joint disease. Myositis may lead to muscle pain and weakness. Erosive joint disease is uncommon. Gastrointestinal involvement may include severe oesophagitis, dysphagia and recurrent upper GI bleeding from antral vascular ectasia (‘water melon stomach’) in up to 20% of patients.

Pulmonary and renal complications are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Fibrosing alveolitis is more common in diffuse disease; pulmonary hypertension is more common in limited disease and CREST syndrome. Hypertensive renal crisis is heralded by malignant hypertension and acute renal failure; it is more common in diffuse disease and may be fatal.

Diagnosis and investigation

The diagnosis is mainly a clinical one. The majority of patients will be ANA-positive; additional anti-topoisomerase-1 and anti-centromere antibodies will be present in 30% of patients with DCSS and 60% patients with LCSS, respectively. Antibodies to Scl-70 are found particularly in pulmonary fibrosis associated with systemic sclerosis.

Management

Patients should be taught simple measures to avoid peripheral cold exposure. No treatment has been shown to be effective in controlling skin disease; however, prompt high-dose antibiotic treatment of local infection is essential. Calcium channel antagonists (e.g. nifedipine) may be effective for Raynaud’s phenomenon. Severe digital ischaemic disease should be treated with regular infusions of intravenous epoprostenol. Steroids can be helpful in myositis and ACE inhibitors should be used to treat hypertensive renal crises (even in the presence of renal impairment). Pulmonary hypertension should be treated with anticoagulation and IV epoprostenol or oral bosentan/sildenafil, depending on disease severity.

Prognosis

The 5-year survival rate is approximately 70%. Poor prognostic features include advanced age at diagnosis, diffuse disease, a high ESR, proteinuria, a low transfer factor or other evidence of pulmonary hypertension.

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis

Epidemiology and aetiology

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis are the commonest forms of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Their aetiology is unknown and genetic associations vary amongst different racial groups. Despite this, there is no significant geographical variation in disease incidence, which is approximately 2–10 per million/year.

Presentation

Both conditions are characterized by muscle weakness and pain. Polymyositis usually presents with progressive symmetrical proximal muscle weakness, e.g. the patient will complain of difficulty rising from a chair, or brushing their hair. The onset is usually over weeks to months, but may be more rapid. Pharyngeal or respiratory muscle involvement is an ominous sign. Interstitial lung disease may develop and is particularly associated with the presence of anti-Jo antibodies.

Dermatomyositis presents with identical muscle features, but additional skin signs. These may include:

• Gottron’s papules: scaly erythematosus or violaceous plaques over the extensor surfaces of the finger joints

• heliotrope rash: violaceous discoloration of the eyelids, usually associated with peri-orbital oedema (Fig. 10.3)

|

| Figure 10.3 Heliotrope rash typical of dermatomyositis. |

• shawl-distribution rash: violaceous eruptions over the shoulders, upper back and upper chest.

Both conditions may be associated with systemic features including fever, weight loss and fatigue and there is an increased risk of malignancy (risk increased by 30% in polymyositis and by 300% in dermatomyositis).

Diagnosis and investigation

Proximal myopathy without neuropathy is highly suggestive, especially if associated with systemic features. CK is often elevated, but a normal CK does not exclude the disease. However, it is a useful means of monitoring disease activity in the longer term. Electromyography will confirm myopathy and the absence of neuropathy. Muscle biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis and will show fibre necrosis and regeneration associated with an inflammatory cell infiltrate. MRI can be used to identify an appropriate area of muscle for biopsy. If underlying malignancy is suspected (based on symptoms or excessive weight loss), screening CT or breast mammography should be considered.

Management

High-dose oral prednisolone (40–60 mg daily) is usually required to achieve control. This can be tapered by 25% per month to a maintenance dose of 5–7.5 mg/day. Patients with pharyngeal or respiratory muscle involvement may require initial treatment with IV methylprednisolone (1 g daily for 3 days). Azathioprine or methotrexate can be used as second-line or steroid-sparing agents. Ciclosporin, cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus and IV immunoglobulin are reserved for refractory disease, in which setting a steroid-induced myopathy should be excluded and consideration given to the need for re-biopsy.

Mixed connective tissue disease

This an overlap syndrome which may include clinical features commonly found in SLE, systemic sclerosis and dermato/polymyositis. Raynaud’s phenomenon is commonly present, in addition to synovitis and oedema of the hands and fingers and muscle pain and weakness. Anti-ribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP) antibodies are often present. Treatment is similar to that of the more specific connective tissue diseases.

DERMATOLOGICAL

The skin is the largest organ of the body and performs several vital functions. It is a barrier to physical agents, ultraviolet light and microorganisms, helps regulate body temperature and prevents loss of body fluids. In addition, it is involved in sensory and autonomic functions, immune surveillance and is essential for vitamin D hydroxylation.

Skin disorders are common and, for patients admitted acutely, it helps to be able to distinguish conditions that require supportive management from those that demand acute investigation or specialist input. In addition, skin changes may act as markers of systemic disease or internal malignancy, a selection of which is listed below:

• coeliac disease: dermatitis herpetiformis

• diabetes: necrobiosis lipoidica, disseminated granuloma annulare, xanthelasma, xanthoma

• thyroid disease: pretibial myxoedema, xerosis

• inflammatory bowel disease: pyoderma gangrenosum

• malignancy: acanthosis nigricans, dermatomyositis, ichthyosis, pruritus.

Assessment

This requires a full history and examination of all the skin with good lighting. Ask about family history, recent medication and contact with possible allergens, such as leather, latex, cosmetics or jewellery. Examine the distribution (e.g. flexor, extensor, palmar, glove or dermatomal), symmetry and morphology of any skin problem and look for evidence of photo-exposure. Record a description of the condition using the mnemonic: ‘Skin Specialists Often Suggest Suncream’ (SSOSS):

• Site on body

• Size (measure with tape measure)

• Outline (clear demarcation or indistinguishable from, e.g., surrounding erythema)

• Shape (linear or round)

• Surface (flat, raised, excoriated, scaly).

The terminology that is used to describe common lesions is unique to dermatology, and you should be familiar with the most basic terms (Table 10.2).

| Terminology | Description |

|---|---|

| Macule | Localized flat area of colour or textural change |

| Papule | Solid elevation, usually <0.5 cm |

| Nodule | Solid elevation, usually >0.5 cm |

| Patch | Localized flat area of colour or textural change, usually >1 cm in diameter |

| Plaque | Raised plateau-like elevation of skin, usually >2 cm in diameter |

| Vesicle | Clear fluid-filled elevation, usually <0.5 cm |

| Blister/bulla | Large fluid-filled elevation, usually >0.5 cm (tense or flaccid) |

| Pustule | Pus-filled elevation, of variable size; may be infected or sterile |

| Excoriation | Scratch |

| Purpura | Bruised discoloration due to leakage of red blood cells |

| Telangiectasia | Collection of abnormally visible dilated blood vessels |

| Lichenification | Thickened skin with prominent markings |

Common inflammatory rashes

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory disease affecting 1–3% of the population (Figure 10.4 and Figure 10.5 overleaf). There is a genetic predisposition, but other factors may also precipitate psoriasis as listed in Table 10.3. There are various clinical phenotypes:

• classic chronic psoriasis: presents as well-defined red plaques with silvery scale, usually on extensor surfaces and scalp

• guttate psoriasis: a more acute eruption (tiny ‘raindrop’ lesions) on torso and limbs that commonly follows a streptococcal throat infection

• flexural psoriasis: glazed red plaques (with little scale) that often affect the axillae, genitalia, gluteal cleft, sub-mammary area and umbilicus

• pustular psoriasis: may be localized, affecting palms and soles with yellow sterile pustules which become brown on healing, or as a more generalized form; see ‘Skin failure and emergency dermatology’, p. 306

• scalp and nail disease: nail pitting, ridging and separation of the distal edge of the nail from the nail bed (onycholysis) are common problems

• joint involvement: psoriatic arthropathy is common and seen in up to 5% of cases and may pre-date skin disease.

|

| Figure 10.4 Chronic plaque psoriasis. |

|

| Figure 10.5 Pustular psoriasis showing pustules of variable size and healing pustules which fade with brown pigmentation. |

| Precipitating factors | Details |

|---|---|

| Infection | Streptococcal sore throat (triggers guttate psoriasis) |

| Drugs | β-blockers, lithium, antimalarials may exacerbate or trigger |

| Sunlight | May exacerbate in a minority of patients (10%) |

| Genetics | Association with HLA Cw6, B13, B17 |

| Trauma (Koebner phenomenon) | Psoriasis may be triggered at a site of injury, e.g. scratch marks giving rise to a linear pattern |

| Stress | Difficult to assess, but a history of significant stress is often obtained |

Treatment

Patients should be reassured that the disease is not contagious and is treatable, but should be aware that most subtypes will relapse. Topical therapy is the safest approach, with emollients providing relief from itch and scale. A number of topical agents can be used, including vitamin D analogues, coal tar preparations, steroids, dithranol, keratolytics and retinoids. Depending on disease severity or the psychological impact of the disease, phototherapy with either narrow-band ultraviolet B (UVB) or ultraviolet A with psoralen photosensitizer (PUVA), or systemic therapy may be needed. If atypical, or poorly responsive to treatment, consider a biopsy to exclude conditions such as cutaneous lymphoma or secondary syphilis.

Eczema

Eczema is a non-infectious itchy inflammatory condition, often also referred to as dermatitis (Figure 10.6 and Figure 10.7, overleaf). Eczema can be classified based its distribution, morphology and aetiology (Table 10.4, p. 297). It may also be described according to the duration of symptoms:

• acute eczema: the cause is usually exogenous and presentation is with redness, papules, oedema, pain, vesicles and, sometimes, large blisters

• chronic eczema: occurs with scaling, fissuring and thickening (lichenification).

|

| Figure 10.6 Flexural atopic eczema. |

|

| Figure 10.7 Venous eczema, with evidence of haemosiderin pigmentation and superficial varicosities. |

| Type | Appearance |

|---|---|

| Atopic | An inherited disease present in up to 15% of infants, although 75% would have cleared before adulthood; in babies, facial involvement is common; in the older child, the pattern changes to flexural disease (antecubital and popliteal fossae); positive family history of atopy (asthma, hayfever, allergic conjunctivitis) is seen in the majority; adults may develop recurrent disease later in life |

| Seborrhoeic | Affects the central area of the face and eyebrows, V of chest |

| Discoid | Scaly itchy circular patches, usually on limbs and torso; often mistaken for ‘ringworm’ |

| Pompholyx | Small vesicles on palms and soles; very itchy |

| Venous | Affects the lower limbs, usually bilaterally, and is linked to venous insufficiency; other features include haemosiderin deposition, lipodermatosclerosis (red tight skin), and ulceration. Frequently misdiagnosed as bilateral cellulites |

| Asteatotic | Dry, fissured (‘crazy pavement’) appearance of skin, usually lower legs, particularly in the elderly |

| Lichen simplex | Heaped up areas of chronic lichenified eczema; common on shins, nape of neck, or readily accessible sites |

With all types of eczema, there may be a superimposed irritant or allergic component. Irritant contact dermatitis may be due to a variety of abrasive and chemical substances, and barrier protection such as gloves is essential.

Allergic contact dermatitis may be identified by history (e.g. reactions to cheap earrings suggests nickel allergy); by examination looking at the distribution of the eruption (e.g. under watchstrap buckle, suggesting nickel allergy); or by patch testing looking for a type IV hypersensitivity reaction. The latter should be considered in anyone with eczema unresponsive to treatment, and with all patients with hand dermatitis.

Treatment

This should include copious emollients, soap substitutes, avoidance of irritants and excessive dust or animal dander, use of protective gloves and cotton clothing. Keeping nails cut short prevents excessive skin damage. In children with atopic eczema, bandaging and wet wraps are a useful adjunct, and sedating anti-histamines may provide some benefit from itch.

Specific treatments include topical steroids, topical immunomodulators such as tacrolimus or pimecrolimus (Elidel®), tar bandages, topical or systemic antibiotics, phototherapy and immunosuppressants.

Lichen planus

This is less common than psoriasis and eczema and presents with extremely pruritic (itchy) polygonal purple papules (Fig. 10.8, p. 297). They often appear in a symmetrical pattern involving wrists, forearms, acral sites and lower legs. In mucosal and genital areas, Wickham’s striae (a lacy white network) and ulceration may be more prominent than papules. Generalized spread may occur and, if nails or scalp are affected, scarring may result.

|

| Figure 10.8 Flat-topped polygonal purple papules of lichen planus. |

Treatment

Although self-limiting, symptomatic treatment with potent or super-potent topical steroids is usually necessary. In more resistant cases, systemic steroids or phototherapy can be used.

Skin tumours

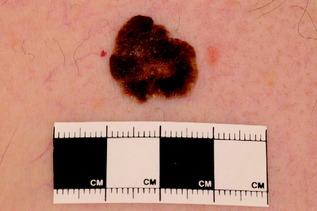

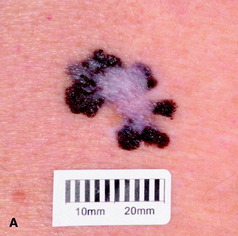

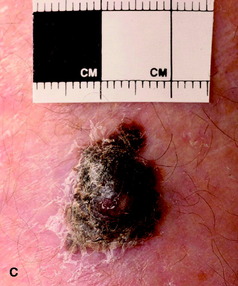

Skin tumours usually present as an incidental finding to the non-dermatologist. It is important that you are able recognize the features of malignant skin disease (Table 10.5 and Figure 10.9, Figure 10.10, Figure 10.11, Figure 10.12, Figure 10.13, Figure 10.14 and Figure 10.15).

| Diagnosis | Description | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Benign lesions | ||

| Seborrhoeic wart (Fig. 10.9) | Common, often multiple and pigmented with a stuck-on appearance; predilection for face and torso | Reassurance |

| Skin tags | Polypoid, flesh-coloured, usually multiple; commonest in axillae, groin, around neck | Reassurance |

| Dermatofibroma | Firm papule or nodule, usually solitary in the legs; sometimes pigmented and/or scaly; dimples when surrounding skin is compressed | Reassurance |

| Pyogenic granuloma (Fig. 10.10) | Red/purple rapidly growing nodule, which bleeds readily; may occur at site of previous injury and is common on fingers; important differential is amelanotic melanoma | Surgical removal for histological assessment |

| Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis | Painful papule on the helix/antihelix of the ear; often mistaken for a basal cell carcinoma but due to inflammation of cartilage | Pressure alleviation, surgery, cryotherapy or topical/intralesional steroids |

| Pre-malignant lesions | ||

| Actinic keratosis (Fig. 10.11) | Scaly keratotic, occasionally red; either single lesion or diffuse change due to excessive ultraviolet exposure; may treat with immunomodulators, e.g. imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil cream | Cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, immunomodulators, diclofenac 3% gel, surgery |

| Bowen’s disease (intra-epidermal squamous cell carcinoma) (Fig. 10.12) | Pink scaly plaque, usually solitary and slow growing; usually seen on the lower legs of older females | Observation; treatments as for actinic keratosis |

| Keratoacanthoma (Fig. 10.13) | Rapidly growing nodule, with thick keratin plug; usually regresses spontaneously within 6 weeks of appearance; may mimic a squamous cell carcinoma | Surgical removal for histological assessment |

| Malignant lesions | ||

| Basal cell carcinoma (Fig. 10.14) | Skin-coloured papule with overlying telangiectasia, pearly appearance and/or rolled edge; slow growing, with risk of local invasion, but rarely metastasizes; four clinical variants | Surgery, cryotherapy, imiquimod, (PDT), radiotherapy |

| Squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 10.15) | Fleshy papule, arising de novo or from a pre-existing actinic keratosis; may progress rapidly to a dome-shaped nodule, or an ill-defined ulcer | Surgery, radiotherapy |

| Malignant melanoma | Macule, patch or nodule, with variable pigmentation, and occasionally loss of pigment either in parts (regression) or completely (amelanotic melanoma); four clinical variants | Surgery, palliative chemotherapy (for advanced disease), regular follow-up |

|

| Figure 10.9 Pigmented seborrhoeic wart. Note the stuck-on appearance, with small inclusions (pseudohorn cysts). |

|

| Figure 10.10 Pyogenic granuloma. |

|

| Figure 10.11 Actinic keratoses. |

|

| Figure 10.12 Bowen’s disease (intra-epithelial squamous cell carcinoma). |

|

| Figure 10.13 Keratoacanthoma showing crateriform periphery and central keratotic area. |

|

| Figure 10.14 Basal cell carcinoma. |

|

| Figure 10.15 Squamous cell carcinoma; commonly occurs on the ear of males. |

Assessment of possible malignant lesions

Itching, bleeding, oozing and crusting are less sinister features. The risk of malignant change in most melanocytic naevi is small, with the exception of large congenital naevi and dysplastic (markedly irregular) naevi.

Melanoma identification

There are various types of melanoma, which you should be able to recognize:

• superficial spreading malignant melanoma (Fig. 10.16a): this is the most common; it predominantly affects the legs and females more than males

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 10.16 (A) Superficial spreading malignant melanoma, showing areas of loss of pigment (regression) centrally. (B) Acral lentiginous melanoma on the sole. (C) Nodular melanoma. (D) Lentigo maligna melanoma, with diffuse pigmentary change. (E) Subungual melanoma (acral). |

• lentigo maligna melanoma (Fig. 10.16b): this most commonly affects the face; if entirely intra-epidermal it is described as lentigo maligna; excision is curative, although it is prone to local recurrence

• nodular malignant melanoma (Fig. 10.16c): the trunk is most commonly affected and males more often than females; tends to grow rapidly and prognosis depends on the depth of the tumour

• acral lentiginous malignant melanoma (Fig. 10.16d,e): most commonly affects the palms, soles and nail beds (subungual); it is often diagnosed late with poorer prognosis.

Common and important problems