KEY TERMS

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

In the spring and summer of 1987, the problem of solid waste disposal was brought to national attention by the plight of the “garbage barge” that could not find a place to unload its cargo. Carrying more than 3000 tons of commercial trash banned from the local landfill in Islip, New York, the barge’s vain search for a disposal site somewhere along the Atlantic or Gulf coasts, Belize or the Bahamas, made national news over a 5-month period. Finally, the barge returned to New York, and the trash was incinerated.1(Ch.16)

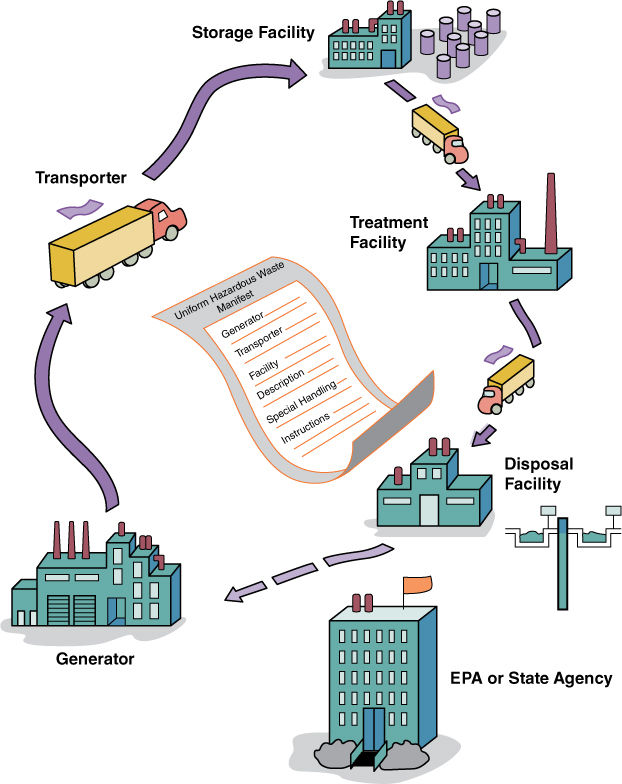

Americans dispose of about 250 million tons of municipal solid waste each year.2 In 2013, this amounted to 4.40 pounds per person per day. Municipal solid waste includes durable goods, nondurable goods, containers and packaging, food scraps, yard trimmings, and miscellaneous inorganic wastes from residential, commercial, institutional, and industrial sources. It does not include construction and demolition debris, automobile bodies, municipal sludges, and industrial process wastes, all of which must also be disposed of in some way. (FIGURE 23-1) gives a breakdown of the composition of municipal solid wastes. The greatest portion of it is paper; much of it is packaging.

Garbage collection has been an important responsibility of local governments since the late 19th century. At that time, it was recognized that rats, flies, and other vermin attracted by garbage carry diseases such as plague and typhus. Even earlier, enlightened cities—including ancient Athens—required that wastes be disposed of outside the city walls.

FIGURE 23-1 Composition of Municipal Solid Waste, 2013

Reproduced from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Municipal Solid Waste Generation (by Material), 2013; 254 Million Tons (Before Recycling),” June 2015. http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/nonhaz/municipal/pubs/2013_advncng_smm_fs.pdf, accessed August 3, 2015.

Until the 1970s, little attention was paid to what was done with the garbage after it was taken away from residential neighborhoods. Most often, it was disposed of in open dumps. Sometimes it was burned, either in incinerators or out in the open, at the dump. Another approach was to pour it into nearby rivers, lakes, or oceans. The drawbacks of these methods became obvious as the volume of garbage increased. Garbage washed up on beaches and contaminated drinking water. Incinerators emitted foul odors, noxious fumes, and black smoke. Dumps, in addition to supporting large populations of vermin, produced toxic leachates that seeped through the soil and contaminated groundwater.

Environmental protection laws banned these methods of waste disposal, which merely transferred garbage from one part of the environment to another. The Clean Air Act made most incinerators illegal; the Clean Water Act outlawed dumping into rivers and lakes; and the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972, with later amendments, prohibited most ocean dumping. Open dumps were outlawed by many states and then by the federal government in 1976 with the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. RCRA (“rickra” as it is known) also set standards for sanitary landfills, which have replaced dumps as the most common method of municipal waste disposal.3(Ch.17)

Sanitary Landfills

Current standards for sanitary landfills require wastes to be confined in a sealed area. A properly designed landfill starts with an appropriate site, which should be dry and consist of impervious clay soil. A large hole is dug and lined with plastic. Refuse is spread in thin layers, compacted by bulldozers, and covered each day with a thin layer of soil. Since decomposing organic matter produces liquids, which may dissolve metals and other toxins, and potentially explosive gases, vents and drains must be constructed to control these hazards. In recent decades, some landfills have collected the gases and used them directly as an alternative fuel or burned them to produce renewable energy in the form of electricity.2 When the landfill has reached its capacity, it is covered with a 2-foot layer of soil. The surface can then be used for a park, golf course, or other recreational facility.

The biggest drawback of sanitary landfills as a method of waste disposal is that they take up a lot of space. In many parts of the country there is no shortage of this commodity, but some urban areas are running out of land. It is expensive to transport garbage from crowded areas to disposal sites with plenty of free space. A measure of the availability of landfill space is the “tipping fee,” the cost for disposing of a ton of municipal solid waste. In 2013, the average tipping fee in the United States for burial in a landfill was $48.73 per ton.4 The northeast generally has the highest tipping fees; the fee in Massachusetts was $78.50 and in Maine it was $91.00.4 Complicating the problem for cities is the phenomenon known as “NIMBY,” meaning “not in my backyard.” People do not want a landfill in their neighborhood. Even people in areas of the country that have plenty of open space resist the idea of having to accept garbage sent from faraway cities.

The problem is epitomized by the garbage crisis in New York City, brought to a head by residents’ complaints about the Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island, a relatively rural borough located within city limits. Fresh Kills began taking garbage in 1948, and by 1996 it was accepting about 13,000 tons per day. It never met even minimal environmental standards, and in 1996 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ordered it to cut down on emissions of noxious gases.5 Meanwhile, the city’s Department of Sanitation proposed to conduct regular tours of the site—“the world’s largest dump”—a proposal which horrified city authorities and was promptly squelched.6 Mayor Rudolph Giuliani then proposed to close it down. Fresh Kills was closed, with much fanfare, in March 2001. Except for its use to dispose of World Trade Center debris after September 11 of that year, the site has remained closed. Since then, the city has struggled with the difficulties of sending the wastes to landfills in other states, mostly Pennsylvania and Virginia. City sanitation trucks took the 12,000 tons of residential wastes per day to transfer stations in the five boroughs and New Jersey, where it was loaded onto tractor trailers for the trip. Roughly the same amount of commercial waste is managed by private carting companies, but it ends up in the same place. The total cost to the city of disposing of a ton of trash in 2004 had risen to $75—40 percent more than it cost in 1997, and there was concern about the willingness of Pennsylvania and Virginia to continue accepting New York’s garbage.7 In 2006, the city published a comprehensive solid-waste management plan, designed to address environmental issues, to increase reliability, and to reduce cost. The plan, which is now being implemented despite many controversies, includes an increase in recycling, a shift from reliance on trucks to trains and barges for carrying trash out of the City (to reduce pollution and fuel costs), and an attempt to find landfill space within New York State.8

Meanwhile, Fresh Kills is being turned into a park. The mountains of garbage need to settle and then will be capped with more than two feet of soil. Work is underway to turn the former landfill into acres of marshes and streams full of wildlife, as well as paths for hikers, bikers, horses, and cross-country skiers. The park currently holds occasional events and tours. It will be opened in phases through 2016.9,10

Alternatives to Landfills

Currently, about 53 percent of municipal solid waste, as well as wastes from other sources, is disposed of in landfills.2 It is obvious that the garbage crisis could be eased if the volume that goes to landfills could be reduced. The only way to make landfills last longer is to apply the “three R’s”: reduce, reuse, and recycle. Prevention of a disposal problem by reducing waste materials at the source is obviously the most efficient approach. Consumer behavior holds the key to successfully reducing waste by this approach. It requires people to buy only the amount of a product that will be used, to choose items without excessive packaging, and to use reusable napkins, towels, diapers, dishes, and cups rather than the disposable variety. The popularity of yard sales is a favorable trend toward achieving reduction of waste through reuse. Although governmental action to encourage the reduction of wastes is still not widespread, there are steps that some communities have taken as incentives. Some residential garbage-pickup services charge by the bag, encouraging residents to cut down on volume. Some states impose taxes on hard-to-dispose-of items such as tires, batteries, and motor oil.

Recycling, technically called resource recovery, is rapidly growing as a method of reducing the amount of waste that must be put in landfills. In 2013, about 34 percent of municipal solid waste was recycled nationwide.2 Providing curbside collection of separated recyclables is a way that communities encourage recycling. Having refundable deposits on bottles and cans is a very effective way to encourage recycling. As of 2015, 10 states require deposits; recycling rates are 70 to 90 percent in these states, about 2.5 times the rate in states without bottle bills. Michigan, which raised its deposit to 10 cents per bottle, the highest in the nation, has a recycling rate of 95 percent.11

The greatest obstacle to the growth of recycling is a lack of a market for used glass, metal, plastic, and paper. Paper is a special problem; it constitutes such a large proportion of trash, and yet it cannot be recycled indefinitely because the fibers break down. Some states require that newspapers contain a specified minimum percentage of recycled fiber. Since governments use large quantities of paper, they can make a significant impact on the recycled paper market. Some states and cities have passed laws requiring recycling of paper or use of recycled paper. About 65 percent of paper and paperboard is currently recycled. Because a healthy market for recyclables depends on their use for new products, the economic downturn in 2008 and 2009 had a negative impact on the market for all recycled materials. Recycling will remain cost-effective, however, as long as the price of placing trash in landfills remains high.1(Ch.17)12

Composting is a form of recycling that allows the natural decay processes to convert yard and food wastes to mulch, useful in gardening. Composting may be done on an individual or municipal level. Some communities mix their compost with sewage sludge to produce a rich fertilizer for agricultural uses.

Another approach to useful disposal of solid waste is waste-to-energy incineration, which both reduces solid waste and produces heat and energy. Special incinerators for this purpose have been designed to minimize the emission of air pollutants. However, the possibility still exists that they may emit toxic gases, including dioxins and furans from the burning of plastics, lead, cadmium, and mercury vapors from batteries mixed in with municipal wastes. Incinerator ash must be disposed of as a hazardous waste, because it frequently contains dangerous levels of heavy metals. NIMBY opposition tends to make finding a site for a waste-to-energy incinerator politically difficult, and building and operating one is expensive because of all the safety features required. About 13 percent of municipal solid waste is disposed of by incineration.2

Hazardous Wastes

A small but significant percentage of solid waste is hazardous waste. These are materials that are toxic to humans, plants, or animals; are likely to explode; or are corrosive and thus likely to burn through containers or human skin. Two special categories of hazardous wastes that are regulated under separate laws are radioactive wastes and infectious medical wastes.

The problem of hazardous waste disposal first came to public attention in 1978 when Love Canal made the news. Residents of a 20-year-old housing development in the town of Niagara Falls, New York, had been noticing some alarming phenomena. After a season of heavy rains and snowfalls, noxious chemicals had begun to bubble up in backyards and seep into basements. Chemical odors were prevalent. Children developed rashes and watering eyes after playing outdoors. Heavy rains washed away soil to reveal buried metal drums, which were corroded and leaking. Reports began to circulate of cancer, birth defects, miscarriages, and other health problems among residents of the area. The alarmed citizens demanded that something be done.1(Ch.17)

The New York State Health Department and the EPA began to investigate. Analyses of soil samples from backyards, air samples in the basements of homes, and water samples in sump pumps and storm sewers revealed contamination by more than 200 different chemicals, including benzene, dioxin, pesticides, and a number of other known carcinogens and teratogens. In August 1978, President Carter declared Love Canal a federal disaster area. Over the next several years, hundreds of Love Canal families were evacuated from their homes.1(Ch.17)

The source of the problem was an abandoned industrial dump, a trench originally intended to be a canal but never finished, which was used by a chemical company for disposal of its wastes over a 10-year period. In 1952, the trench was declared full and covered with soil. The city took over the property to build a school. By the time home building began in the neighborhood several years later, most people had forgotten about the former activities at the site, and it did not occur to anyone that the area might be hazardous.

Over much of the same period that the Love Canal problems were taking place, another hazardous waste drama was playing out in Missouri. The first act consisted of several episodes in 1971, when waste oil was sprayed on the floors of several horse arenas around the state, a practice used to keep the dust down. After the spraying, a wave of mysterious illnesses began affecting animals and people who came in contact with the dirt. Several children were sickened, some with chloracne, and some had to be hospitalized with severe flu-like symptoms. Horses were badly affected, and many died. Hundreds of dead birds were found in the area. The waste oil was suspected, but the hauler claimed there was nothing unusual about the oil. Investigators from the Missouri Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) could find nothing unusual in the soil samples or in the blood of the victims. Meanwhile, the same hauler had been hired to spray oil on 23 miles of dirt roads in Times Beach, a community of about 2000 people near St. Louis, during the summer of 1972 and during each of the next four summers.14

CDC scientists continued to run tests on the soil from the horse arenas, and in 1974 they identified dioxin at concentrations as high as 31,000 parts per billion (ppb). This was more than high enough to cause human illnesses and the deaths of animals. Further investigation revealed that the oil hauler had been hired by a chemical company to dispose of wastes from the manufacture of Agent Orange, the herbicide used in the Vietnam War. The hauler was mixing this waste oil with used crankcase oil and using it for his spraying operations. The CDC was able to trace the hauler’s activities and discovered Times Beach, among other places, where no problems had been suspected. That was in 1982, at just about the time when the community was inundated by a flood, which, it was feared, spread the dioxin throughout the town. Tests found dioxin levels on the order of 100 ppb on roads and in yards. Residents panicked.14

In the end, Times Beach, like Love Canal, was evacuated. In retrospect, the decision has been widely criticized as an overreaction. The levels of dioxin in Times Beach were much lower than those in the horse arenas, and more modest remediation would probably have sufficed. However, little was known at that time about the toxicity and carcinogenicity of dioxin in humans. The effects on animals were certainly a cause of concern.

Love Canal residents have been carefully tracked for health outcomes that might be associated with the exposures. The New York State Department of Health interviewed over 6000 former residents between 1978 and 1982, and in 1996 it began searching records of births and deaths and state registries of cancer diagnoses and congenital malformations for evidence of health problems. In a report of the study published in 2008, there was clear evidence of adverse reproductive outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth, among women who had lived at Love Canal. Especially notable was the finding that women who had been exposed to waste at Love Canal as children were twice as likely to give birth to infants with congenital malformations than were comparable women who had grown up elsewhere. There were also indications of an increased risk of some forms of cancer, especially lung cancer.15 The follow-up of these residents will be continued.

RCRA, the federal legislation first enacted in 1976 to deal with solid waste disposal, included special regulations on handling of wastes that potentially posed a hazard to health and the environment. These regulations, which were strengthened by amendments to RCRA in 1984 and 1992, can prevent future Love Canals and Times Beaches. They require that all hazardous wastes be accounted for “from cradle to grave,” and there are criminal penalties for those who violate the laws. However, legal disposal of hazardous wastes is expensive, and no one knows how much illegal “midnight dumping” may actually go on today.1(Ch.17)

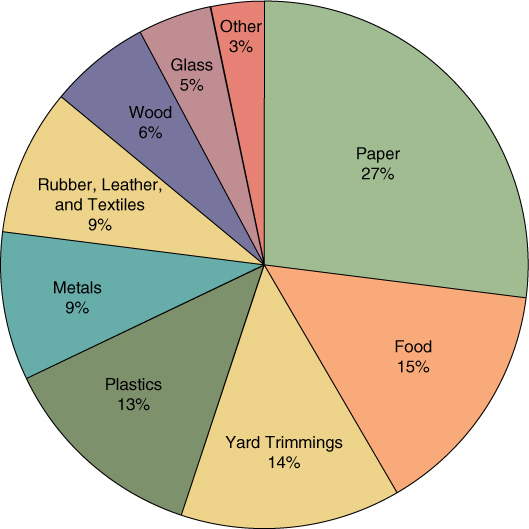

RCRA lists many specific wastes that are regulated under the law, including wastes from petroleum refining, pesticide manufacturing, and some pharmaceutical products. Wastes are also considered hazardous if they are ignitable, corrosive, reactive, or toxic. The regulations are stricter for large-quantity generators, facilities that generate more than 2200 pounds per month, than for small-quantity generators, facilities that generate between 220 and 2200 pounds per month. Facilities that generate the smallest amounts of waste are subject to only minimal requirements. The RCRA regulations have two key elements: tracking and permitting. The tracking requirement, illustrated in (FIGURE 23-2), mandates that paperwork document the progress of hazardous waste from its site of generation through treatment, storage, and disposal. Permitting means that any facility that treats, stores, or disposes of hazardous waste must be issued a permit from the EPA or the state; the permit prescribes standards for management of the waste. Transportation of hazardous waste, which must be clearly labeled, is regulated by the U.S. Department of Transportation.16

According to the EPA, over 40 million tons of hazardous wastes are managed annually under the RCRA regulations.17 As with municipal solid waste, hazardous waste is managed by practicing the three R’s: reduce, reuse, and recycle. One way of reducing the waste is by treating it to make it less hazardous; this can be done, for example, by biological or chemical treatment, by burning the waste at high temperatures, and by separating solids from wastewater to reduce the volume of waste that must be disposed of. A common method of disposing of liquid hazardous waste is by injecting it under pressure into underground wells encased with steel and concrete. Specially designed landfills are also used for disposing of hazardous waste. Efforts to reduce the generation of hazardous wastes have paid off, however, and the volume that needs to be disposed of is much reduced from previous decades.18

While RCRA was meant to control hazardous wastes as they are generated, it was inadequate to deal with old waste sites that kept turning up in the news after the public consciousness had been raised. In response, in 1980 Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, known as “Superfund.” That law required the EPA to compile a priority list of waste sites that threatened the public health or environmental quality, and it authorized $1.6 billion over a 5-year period for emergency cleanup of these sites. The cleanup was paid for by a tax on industry, which created the trust fund that gave the program its name. Superfund was reauthorized in 1986 and 1990, allocating additional billions of dollars for cleanup.3(Ch.17)

The Superfund program has been mired in controversy from the beginning. The pace of the cleanup has been slow, and the cost has been very high. New sites are being added to the priority list more rapidly than old sites are being cleaned up and removed. As of February 2014, there were 1321 sites on the list and 51 sites had been proposed for addition. Cleanup had been completed on 388 sites, which had been deleted.19 Because the legislation calls for polluters to pay, a great deal of effort has been spent on trying to establish who is liable. Congress did not reauthorize the corporate taxes that paid into the trust fund when the tax expired in 1995, and the fund has been exhausted. Although cleanup of many sites is going forward, paid for by the polluters—for example, General Electric Company is paying for the dredging of the Hudson River—cleanup of “orphan” sites, for which the responsible company could not be identified or could not pay, is now being paid for with taxpayer dollars. The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act allocated $600 million to facilitate further cleanup of Superfund sites, giving hope that the most contaminated sites can be addressed.3(Ch. 17)