Chapter 21

Social determinants of health

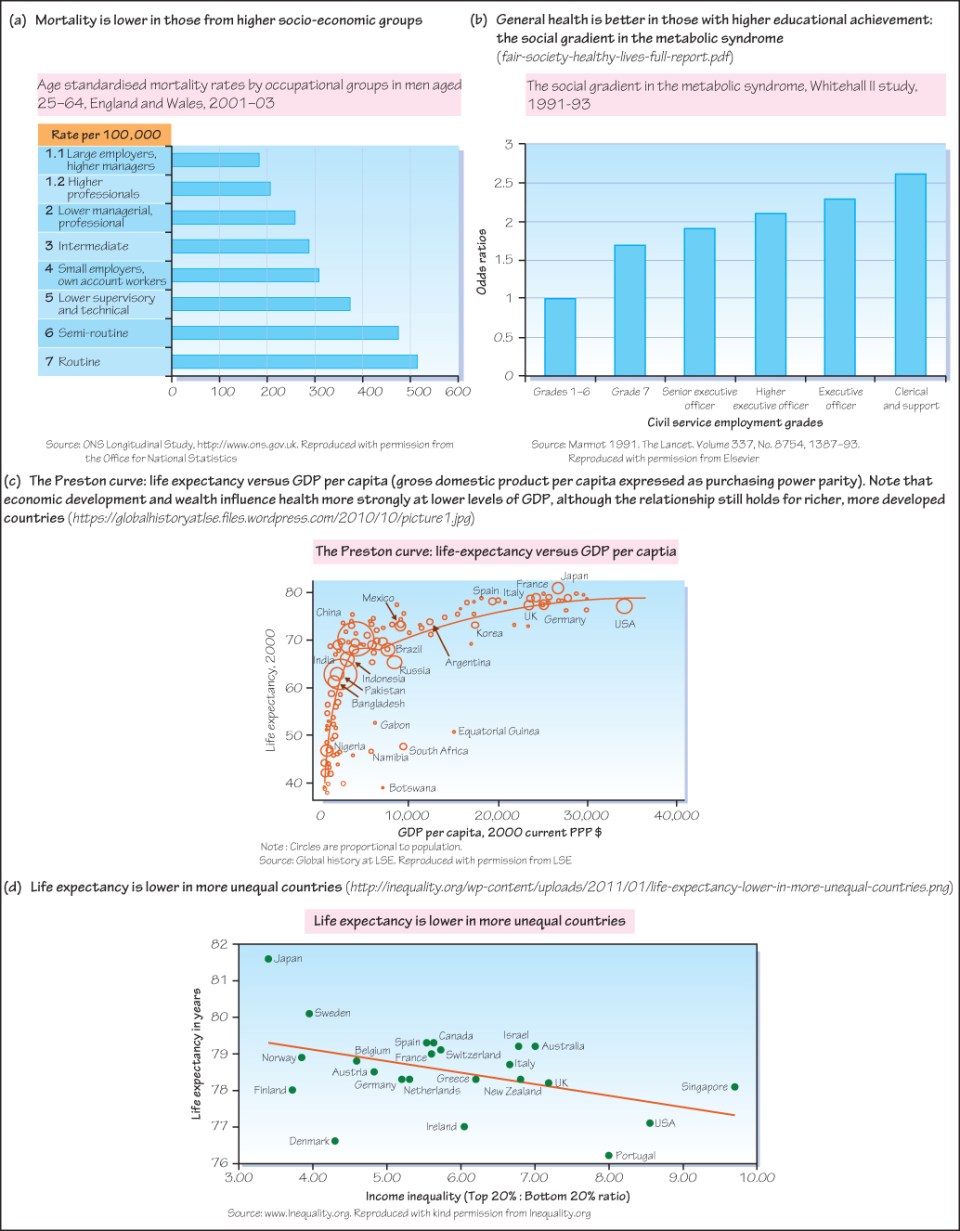

The nineteenth-century sanitary movement recognised the importance of living and working conditions in influencing health: poor housing, over-crowding and lack of clean drinking water and sewage disposal all contributed to high levels of communicable diseases. Building sewers and improving housing improved the health of the urban poor. Living and working conditions continue to influence health status, although communicable diseases are now replaced with chronic non-communicable conditions.

As with health behaviours, adverse socio-economic determinants of health cluster in certain groups and geographical areas; they are also cumulative across the lifecourse. An individual from a poor background may be less ready for schooling at the age of 5 years than his/her more affluent peers, fail to achieve good educational qualifications, resulting in obtaining lower paid and less secure employment, a poorer standard of housing and lower overall wealth. Inequalities in health follow from this unequal distribution of these underlying determinants, which form the basis of the classification of socio-economic status (see Chapter 23).

Work and employment

Being gainfully employed is generally good for health: those who are unemployed have generally poorer health than those who have a job, although it is important to recognise that those who are already in poor health may not be able to find work or continue with their pre-morbid employment. Paid work is less beneficial to health if the work is low paid, insecure or not satisfying. Amongst the employed, those whose jobs provide more control over their work patterns generally have better health than those who have little control (Figure 21a). Unemployment results in poorer health of individuals and their families across all social groups; financial loss, distress, anxiety, depression and increases in unhealthy behaviours such as smoking and alcohol consumption all contribute.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree