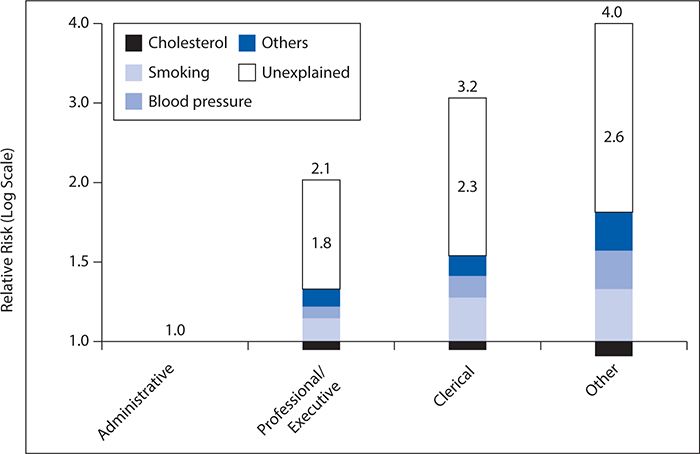

Figure 5-1. Linear relationship between job grade and mortality. CHD, congestive heart disease. (Reproduced with permission from Marmot MG, Rose G, Shipley M, Hamilton PJ. Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978;32(4):244-249.)

This seminal study identified the profound effects of social factors, such as job status, in the production of health and ushered in an era of evolving research highlighting the compelling and complex relationship between health and societal forces. In this chapter, we will explore the relationship between social factors and health outcomes; review emerging themes in this area, including a life-course perspective on the social determinants of health; and suggest intervention strategies that reflect the profound causal relationships identified by the Whitehall studies.

OVERVIEW

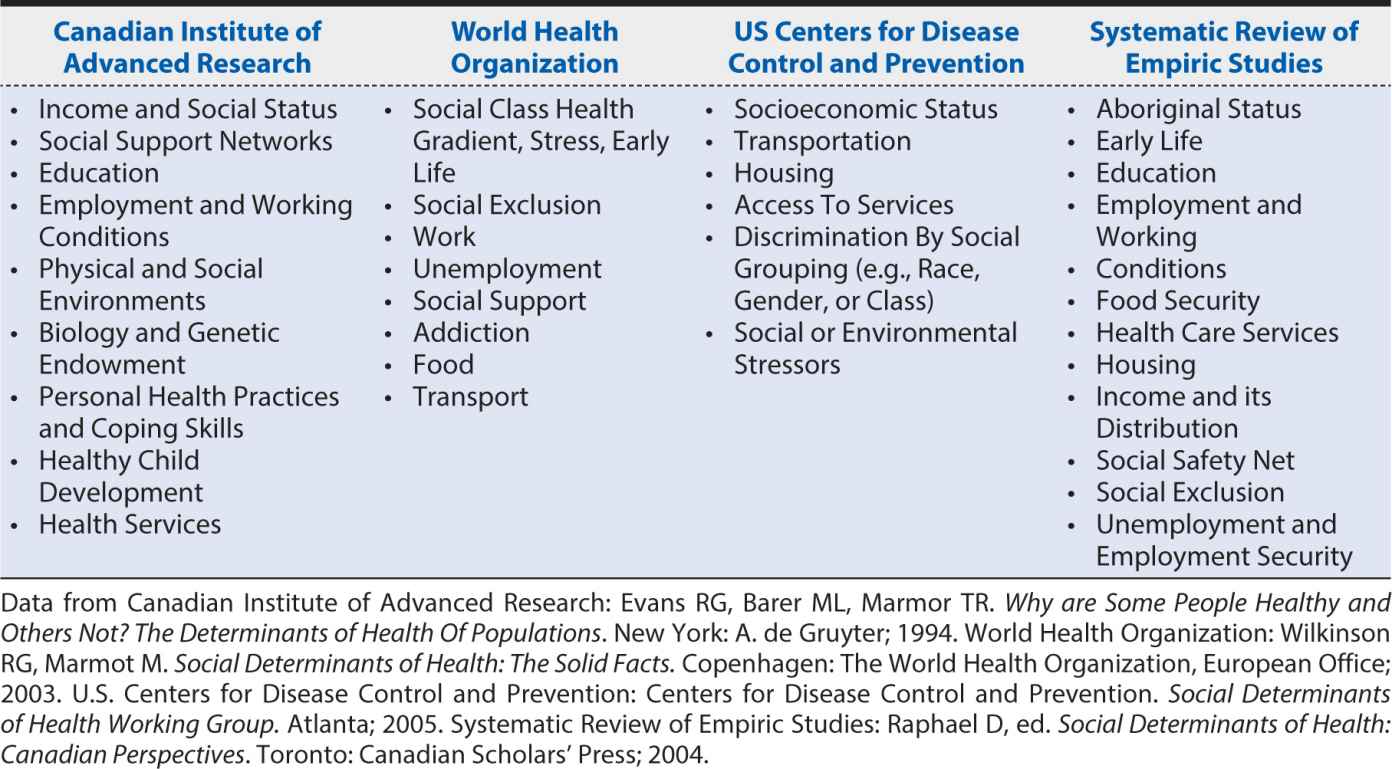

There is growing recognition that the health of individuals and populations is strongly influenced by factors beyond biomedical and behavioral risk factors. In recent years, the term “social determinants of health” has been used to capture these wide-ranging factors. This term grew out of research focused on identifying the mechanisms by which members of differing socioeconomic groups came to experience varying degrees of health and wellness. There are a variety of approaches to characterizing the social determinants of health, but all focus on the organization and distribution of economic and social resources. As shown in Table 5-1, wide ranges of economic and social resources have been examined in the study of social determinants of health. A World Health Organization (WHO) workgroup in 2003 charged with the task of identifying the social determinants of health included social gradient, stress, early life, social exclusion, work, unemployment, social support, addiction, food, and transportation. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention highlighted socioeconomic status, transportation, housing, access to services, discrimination by social grouping, and social or environmental stressors in their listing.

Table 5-1. Economic and social resources assessed as social determinants of health.

Support for the importance of social determinants of health can be found in several lines of research, including the classic Whitehall study described earlier. Studies of causes of the profound improvement in health status in individuals living in developed nations over the past 100 years emphasize the importance of social determinants in population health. Although advances in health care are clearly responsible for some increased longevity over the past 100 years, most analyses conclude that improvement in conditions of everyday life related to early life, education, food processing and availability, housing, and social services are responsible for a large percentage of the health status improvement. The importance of social determinants of health is also supported by the vast health differences observed among populations within the same nation and the differences in population health seen between different countries with similar levels of development and socioeconomic status.

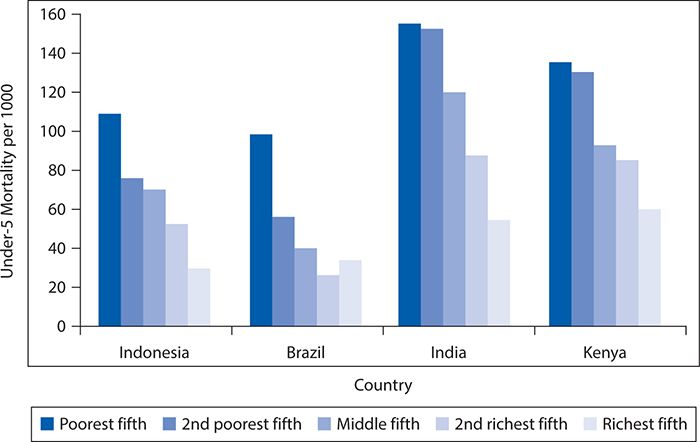

The operational relationships between the various factors that constitute the social determinants of health are overlapping and complex. Clearly, poverty is an underlying issue of importance in determining access to health care, food, transportation, and adequate housing. Childhood (younger than age 5 years) mortality is the health outcome most sensitive to poverty. In Figure 5-2, mortality rates for children younger than age 5 years by socioeconomic status across four countries are displayed. As can be seen, although child mortality varies widely among countries, within any one country, there is a consistent social gradient with the highest child mortality rates in the poorest households. There are a number of examples of countries with similar incomes, but strikingly different health records, however. Greece, for example, with a per capita gross national product (GNP) of just more than $17,000, has a life expectancy of 78.1 years, but the United States, with a per capita GNP of more than $34,000, has a life expectancy of 76.9 years. Costa Rica and Cuba both have per capita GNPs less than $10,000 and yet have life expectancies of 77.9 years and 76.5 years, respectively. A recent Institute of Medicine study found that the United States ranks poorly in terms of both prevalence and mortality for multiple diseases, risk factors, and injuries compared with 16 comparable high income or “peer” countries. This U.S. health disadvantage is not limited to socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, but even the most advantaged Americans are in worse health than their counterparts in other “peer” countries as shown in a report by the Institute of Medicine in 2013.

Figure 5-2. Mortality rates for children younger than age 5 years by socioeconomic status across four countries. (Reproduced with permission from Victora CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet. 2003 Jul 19;362(9379):233-241.)

Where material deprivation is severe, a social gradient in mortality is more likely to be a function of the degree of absolute deprivation. In rich countries with relatively low levels of material deprivation, the focus changes from absolute to relative deprivation. With respect to relative deprivation, consideration of the impact of a broader approach to human needs is critical. This means considering the importance of both material and physical needs and capability as well as spiritual or psychosocial needs on human health. Consistent with this approach toward the relationship between the level of material deprivation and social determinants of health, in Africa the major contributor to premature death is communicable disease, while in every other region of the world, noncommunicable disease makes the largest contribution to premature mortality. Analysis of the global burden of disease in developed countries has emphasized the importance of risk factors, such as being overweight, smoking, alcohol, and poor diet, a different set of social determinants than those that dominate in countries with higher indices of poverty (see Chapter 4).

EMERGING THEMES IN SOCIAL DETERMINANTS

An overarching theme that cuts across the various disciplines and theories addressing social determinants of health is that social factors, independent of behaviors and biologic causes, strongly influence population-level health. The idea that societal factors are strong precursors to health outcomes is not a new concept. In the 19th century, a host of theorists described political, economic, and social correlates of disease and mortality. Although there is widespread acceptance that the distribution of social and economic resources is highly correlated with health, there is also a wide range of theoretical approaches regarding the causal mechanisms for these effects. Empiric data show that since the beginning of the 20th century, there have been large-scale improvements in human health. It is widely assumed that this is the byproduct of the development of technological advancements of industrial societies that allow them to deliver more effective and high-quality health care and that human behavior has changed in ways that lead to longer, more healthy lives. Yet multiple scientific studies have shown that only about 10% to 15% of the improvement in longevity since 1900 can be accounted for by improved health care, and health behaviors themselves are highly correlated with the material conditions of everyday life. These findings imply that there is something more fundamental than access to health care and individual behaviors actually driving health outcomes. One key factor that emerges across theories is that societal inequality is a major driving force behind social determinants of health. Three major theoretical perspectives have been advanced in this regard: materialist, neomaterialist, and comparative psychosocial theories.

Materialist theories of the social determinants of health are the earliest theories that emerged, and they persist to this day. The materialist approach argues that access to resources is the most basic driving force in determining the quality of health of both individuals and populations. Those with greater income, wealth, and the associated material possessions that income and wealth generate are posited to have the best health and longest lives. Empirical data well justify this assertion. For example, the overall wealth of a nation is a very strong predictor of the quality of health of its population. Within nations, wealth is well documented to be associated with health such that individuals with a better socioeconomic position are more likely to have better health and longer lives. As noted by Raphael (2006), “Material conditions predict likelihood of physical (infections, malnutrition, chronic disease and injuries), developmental (delayed or impaired cognition, personality, and social development), educational (learning disabilities, poor learning, early school leaving), and social (socialization, preparation for work and family life) problems.” Poverty also is associated with increased stress, which itself is highly associated with poor health outcomes, both physical and psychiatric. In addition, unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and substance abuse sometimes have been associated with poverty, perhaps as a strategy to cope with stress and deprivation.

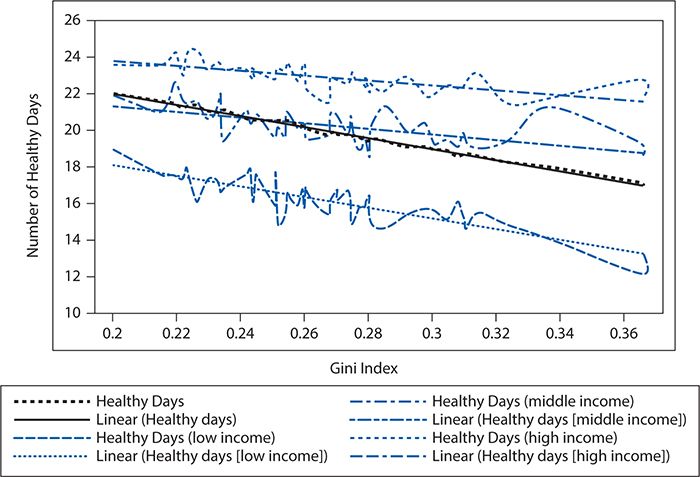

Neo-materialist theories have a slightly different perspective on the role of wealth as a primary social determinant of health. These theorists argue that the production of health is not related to just the absolute level of material resources available but also to the relative distribution of resources. For example, although a nation may be wealthy overall, health will be affected negatively if there are wide gaps in how resources are distributed across population groups or geographic areas. In essence, neo-materials posit that health is not just a function of how wealthy a nation is but also how equal the population is within the nation. A host of research has shown that indeed there is a relationship between the level of inequality in a society and health, and this relationship is independent of the overall level of wealth. An example can be found in Figure 5-3, which shows the relationship between the Gini coefficient (high values represent higher levels of inequality) and various measures of health status. The graphic shows that poor individuals have fewer healthy days, and this effect is amplified with greater levels of inequality across members of a community.

Figure 5-3. The relationship among wealth, inequality, and health. (Reproduced with permission from Frieden TR. Forward: CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report—United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(suppl):1-2.)

Finally, the neo-materialist perspective has been elaborated on with regard to causal mechanisms related to psychosocial comparisons that emerge from inequality. In this theoretical perspective, the degree of perceived hierarchy and social distance that occurs in a society is thought to be correlated with health outcomes. The primary tenet of the psychosocial comparison perspective is that one key mechanism by which health is produced in the psychological self-perception that members of society have with regard to their standing in the social hierarchy. There are two primary mechanisms that drive these effects: (1) through the stress derived from feeling unequal and (2) from the reduction in communal “social capital” that results from inequality. In the first instance, societal inequality is thought to directly promote stress among individuals, and as discussed earlier, stress is associated with poor health. The second mechanism, reduction in social capital driven by inequality, is a process by which the ties that bind people together in communities (also known as “social capital”) are eroded by inequality, and this results in a diminution of health through distrust of others, a lack of social support, and smaller social networks, which can disadvantage people in navigating complex health care systems. These theorists argue that social cohesiveness promotes better population health.

One challenge when exploring the relationships between health and its social determinants is that the myriad relationships between health and such factors as access to material resources, inequality, self-perceptions of equity, communal ties, and social capital are linked in complex ways. Although there are strong empirical correlations between these variables and health outcomes, as has been described earlier, the pathways and mechanisms by which social forces impact health are difficult to tease apart. One emerging discipline that has attempted to do this is social epidemiology, a branch of epidemiology that concerns itself with the relationship between social forces and disease, with an emphasis on bringing rigorous epidemiologic methods to the study of these relationships. These scientists have focused on both what are known as “horizontal structures” (proximal variables experienced by an individual, such as the family structure and work environment) and “vertical structures” (distal variables, such as larger scale political and economic forces), as well as how these two interact. This is a rich area of inquiry that has provided insight into the specific causes and pathways for the influence of social variables on health.

THE LIFE-COURSE PERSPECTIVE ON SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Although traditional approaches to health and prevention efforts emphasize addressing biomedical risk factors and unhealthy behaviors in a contemporaneous manner, life-course approaches, which emphasize the accumulated impact of experiences across the lifespan on health, may make more sense in addressing the social determinants of health. In particular, investment during the early years of life has great potential in reducing health inequities. For example, brain development is highly sensitive to external influences such as good nutrition (including in utero), nurturing, and psychosocial stimulation. There is accumulating evidence to support the fact that early nutrition and experiences impact the risk of developing obesity, heart disease, mental health problems, and criminality in later life. Early childhood experiences also have long-lasting impact on subsequent health and quality of life through skills development, education, and occupational opportunities.

Hertzman (1999) describes three classes of health effects that are relevant to a life-course perspective. Latent effects refer to biologic or developmental early life experiences that impact health later in life. The association between low birth weight and adult-onset diabetes and cardiovascular disease is one example of a latent effect. Recent studies demonstrate that adolescent cannabis use is associated with neuropsychological decline across multiple domains of function that is not fully restored with abstinence. This is likely associated with the poorer education achievement, lower earning potential, increased social welfare dependence, and decreased life satisfaction seen in individuals who were heavy cannabis users in adolescence.

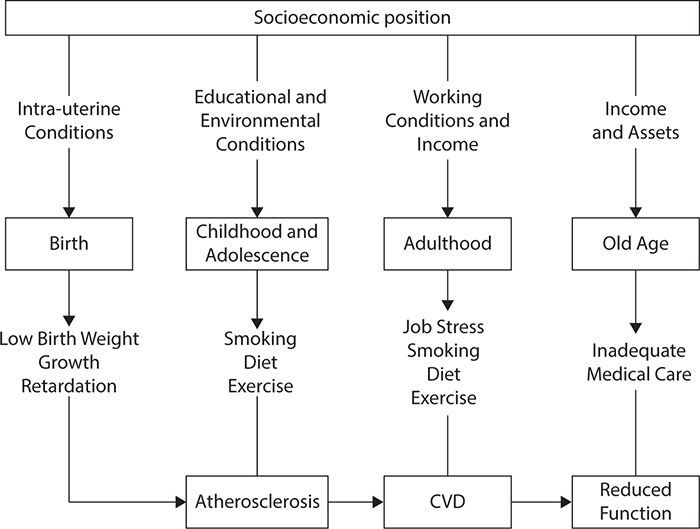

Pathway effects refer to experiences that set individuals onto trajectories that influence health and well-being over the course of a lifetime. For example, entering school with delayed cognitive development can lead to lower education expectations, poorer employment opportunities, and a greater likelihood of illness across the lifespan. Cumulative effects refer to the accumulation of advantage or disadvantage over time, which manifests in health status. Cumulative effects can operate through latent or pathway effects. The life-course perspective allows for consideration of how social determinants of health operate at every level of development to immediately influence health and to provide the basis for health and illness later in life. As an example, the Australian National Public Health Partnership conceptualized the risk of tobacco use with a social determinants perspective that also considered the specificity of effects over the lifespan, as shown in Figure 5-4.

Figure 5-4. Socioeconomic influence on cardiovascular disease (CVD) from a life-course perspective. (Reproduced with permission from The National Public Health Partnership. National Public Health Partnership. Preventing Chronic Disease: A Strategic Framework. Background Paper. http://www.nphp.gov.au/publications/strategies/chrondis-bgpaper.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2014.)

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2005, the WHO established a Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, led by Marmot and colleagues, to foster attention on the role of social determinants of health and make recommendations for interventions. The Commission’s analysis and recommendations are codified in a final report published in 2008. This report highlighted three key areas for interventions: (1) improving daily living conditions; (2) reducing the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources; and (3) measuring and understanding social determinants of health to better plan interventions. This seminal report articulates well the key opportunities for interventions and stresses the role of government policy and international cooperation in maximizing human health through interventions whose primary focus is to improve health by addressing its social determinants. In this section, we summarize many of the core intervention recommendations highlighted in the report.

To improve daily living conditions, a fundamental strategy is to first improve life chances by enhancing early childhood development, including physical, cognitive, linguistic, social, and emotional development. Major strategies to achieve these goals include enhancing prenatal care, child nutrition, support to families for safe and supportive living environments for children, and access to quality preschool education. There is also potential to improve daily living conditions by improving the physical environment in which people live. Urbanization is dramatically increasing globally, and this is leading to an associated increase in population health problems dominated by noncommunicable diseases, accidents, and violent injuries. A large proportion of such risks can be mitigated through improved housing and shelter, improved access to clean water and sanitation, land use policies that minimize dependence on cars for transportation, automobile safety enhancements, and urban planning that supports healthy and safe behaviors. In rural settings, there are special needs with regard to access to services, poverty reduction, access to land, and links to transportation.

Another key component of improving daily living conditions is fair employment and decent work. Work is considered a fundamental social determinant of health because it consumes a large amount of life’s efforts, subjects people to risks, is a major determinant of social status, affects self-esteem, and provides necessary income. Temporary workers also have much higher mortality rates than permanent workers, and unstable employment is associated with poor mental health. Poor working conditions, especially prevalent in low-income countries, expose workers to health hazards, especially among poorly paid employees. It is notable that occupations in which workers have little control over their work result in significantly greater health problems, such as was described in the Whitehall study earlier, an effect consistently identified in numerous other studies. Interventions to improve access to decent and fair work include provision of a living wage, strong protective health and safety standards in the workplace, a reasonable balance between work and life and home and life, and giving workers a voice in operational decision making, especially those that affect the worker’s direct work activities.

Another major intervention area highlighted by the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health is the need for social protection to ensure that unexpected events in a person’s life do not lead to impoverishment. In all countries, rich and poor, virtually everyone will need assistance during vulnerable periods of their lives such as during periods of illness, unemployment, and disability. There is strong evidence that government policies such as social welfare and social security insurance programs have an enormous impact on mitigation of the dire effects of vulnerability and the associated negative impacts on health. Moreover, there is also evidence that countries with strong systems and policies of social protection have significantly lower rates of poverty and healthier people, and they have more resilient economies better able to rebound in periods of economic recession. Examples of such effective policies include setting minimum living standards, financial support and job retraining during periods of unemployment, and systems that guarantee basic pensions in old age.

Finally, one of the most important social determinants of health identified by the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health is the need for universal access to health care. Health care in virtually all countries in the world, both rich and poor, is considered a basic human right, and the vast majority of countries worldwide have systems of government-financed universal health care. Some countries finance their systems through taxation and others through mandatory universal insurance, and the degree to which the state or private sector provides care also varies widely. Regardless of whether health care is financed and provided through public or private means, equitable access to health care as a basic human right is a principle that has striking impacts on the quality and length of life. It is estimated that upward of 100 million people annually are impoverished due to health care costs caused by catastrophic illness.

The second major recommendation of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health is to reduce the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources by setting coherent and coordinated policies, both public and private, that maximize health. The Commission stressed the importance of policy coherence to promote societal health. For example, public health policy that stresses good nutrition should not be undercut by trade policies that encourage the production, trade, and consumption of a poor-quality diet. Some policies that could have a major impact on improving health include progressive taxation systems that assure government resources to provide for social welfare programs, increased development aid for the poorest nations, and coordination of foreign development aid that is transparent and evidence based with regard to impact on improving the health and well-being of recipients. In addition, the Commission also strongly recommended that economic markets be regulated to minimize “economic inequalities, resources depletion, environmental pollution, unhealthy working conditions, and the circulation of dangerous and unhealthy goods” and that health and health care not be treated as a commodity to be traded but rather to be considered as a human right accessible to all based on need.

Other polices recommended by the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health include those that foster gender equity, political empowerment, and improved global governance. The Commission notes that although the status of women has improved substantially over the past century, there remain significant challenges for girls and women because they continue to have poor education and employment opportunities globally compared with men. This can be mitigated by, for example, legislation that outlaws gender discrimination; increasing educational opportunities for girls and women; increased funding for sexual and reproductive health; and accounting for housework, care work, and voluntary work. Political empowerment also is pointed to as an important social determinant of health and one that is especially needed globally for indigenous populations, ethnic minorities, the poor, those with disabilities, and members of the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) community. Interventions include state support for comprehensive human rights and the right to social and political inclusion and support and growth of civil society groups that give voice to the underrepresented. In a related vein, there are stark inequalities cross-nationally, and the Commission’s 2008 report stressed the importance of global governance that stresses a multilateral system “in which all countries, rich and poor, engage with an equitable voice.”

This review of possible interventions to address social determinants of health elucidates the far-reaching and complex nature of the topic. One final recommendation in the report from the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health was that we need to know more about social determinants in order to better craft and generate sustained support for interventions to improve health. Therefore, a strong recommendation was made to support the collection of more standardized and complete data on social determinants of health to allow for better analysis of these complex relationships. Without solid and rigorously collected data, it is impossible to unearth the casual forces at play, and it is difficult to generate policy support for intervention strategies. In addition, evaluation data on the efficacy of interventions are a powerful tool to both improve programs and generate societal and policy support for intervening on what has been demonstrably shown to be major causes of morbidity and mortality throughout the world.

CHALLENGES

Despite growing recognition of the importance of social determinants of health, a number of challenges are limiting action and implementation of policies based on this knowledge. As mentioned earlier, one clear need is in the area of basic data systems and mechanisms to ensure that the data can be disseminated and understood. Many countries do not even have basic systems to register all births and deaths, and countries with the worst health problems have the poorest data. Without basic data on mortality and morbidity stratified by socioeconomic indicators, countries will continue to have difficulties moving forward on health equity issues. Good evidence on levels of health and its distribution is essential to understand the scale of the problem, recommend actions to be taken, and monitor the impact of policy and other changes in social determinants that might be affecting public health.

In addition, the evidence base on health inequities and how they can be improved needs further strengthening. Unfortunately, most health research funding remains focused on a clinically oriented, individual patient approach to disease. In addition, research grants often are funded to deal with specific diseases and support researchers working in programs that focus on a particular disease state or risk factors. This emphasis produces a group of disease experts and expertise-driven intervention programs rather than programs that focus on fundamental issues impacting health in daily lives. In addition, traditional hierarchies of evidence that value randomized controlled trials and laboratory experiments above other types of evidence generally do not work for research on the social determinants of health. As such, we need new models for gathering and determining the quality of scientific evidence as it applies to population health and social determinants. Routine monitoring systems for health equity and the social determinants of health are needed. Such systems will enable generation and sharing of new evidence on the ways in which social determinants influence population health and health equity and on the effectiveness of measures to reduce inequities through action on social determinants.

Evidence alone does not ensure changes in the factors impacting social determinants of health, however. Education is necessary so that practitioners, policymakers, and the general public can understand the importance of these social factors. There is little evidence of penetration of concepts related to social determinants of health into either public health discourse or government policymaking. The emphasis on the market as the arbiter of societal functioning in many capitalistic countries conflicts with a social determinants of health approach that requires commitment to equitable income distribution and support of public social infrastructure that provides adequate housing, food security, and strong public health and social services.

Another challenge is the fact that both studying and addressing the social determinants of health is a complex, multilevel process that requires an interdisciplinary approach. If we take, for example, the incredible decline in cigarette smoking rates in the United States over the past 20 years, it is clear that numerous forces in operation at various levels influenced this decline. Knowledge about smoking addiction and treatments from basic and clinical research was applied in developing and using evidence-based treatments for smokers. In addition, there was a great deal of public information about the health risks of smoking, the price of cigarettes was increased, and access to cigarette machines was limited. In addition, severe limitations on advertising and smoking in public places were imposed. In other words, the partnerships and policies that helped to change the prevalence and health consequences of smoking went far beyond the narrow confines of the health care and biomedical research fields.

CONCLUSIONS

The social determinants of health approach offers a window into the processes by which social influences can impact health or illness and an opportunity to consider the processes by which power relationships and political ideology can ultimately influence the health of a population. However, there is much work to be done in gathering the data needed to explicate these social influences and to explore approaches to using social determinants to improve health and quality of life. In particular, bridging the gap between knowledge about social determinants and enacting coherent policies to address critical areas is an enormous challenge that will require breaking out of disciplinary silos with well-coordinated efforts operating at multiple levels.

SUMMARY

Social determinants of health refer to societal factors that contribute to health and well-being or the loss thereof. Variations in health status within human populations according to social class have been recognized since at least the 19th century. The landmark Whitehall Study, however, launched in the United Kingdom 50 years ago, brought great focus to the fact that persons of lower social status had worse health measures even after adjusting for baseline differences in known biomedical and behavioral risk factors.

The economic and social attributes classified under the umbrella of social determinants of health vary by context but typically include some or all of the following: income, education, employment, housing, transportation, food security, social connections and support, and access to health care. Improvements in these conditions over the past century have driven most of the gains in the quality and duration of life during this period. In contrast, technical breakthroughs in health care services account for a comparatively small part of the general progress in health outcomes.

The manner in which social factors have an impact on health is complex. Economic resources are critical to determining access to and quality of many services and therefore have an important impact upon health. This is certainly evident in comparing health outcomes across countries with widely varying economic resources. Even within wealthy countries, however, varying levels of deprivation can be seen and correlated with gradients in health status. Those with fewer resources are likely to experience higher stress and reduced social cohesion, as manifest by greater levels of distrust and inadequate social support and networks. Individually and collectively, these characteristics can adversely affect health and interaction with the health care system. Investigators in the field of social epidemiology focus on understanding the mechanisms by which these attributes interrelate and affect health.

Social factors can impact health along the entire human lifespan, with particular susceptibility during the early years of life when growth and development are most active. Some of these effects may not be observed for years, in part because of multistep processes or the cumulative impact of repeated exposures.

Although there are many gaps in our understanding of the mechanisms by which social factors impact health, the highly reproducible effects have led bodies such as the WHO to make recommendations for reducing these gaps in health. The main thrusts of these proposals are to (1) improve living conditions, (2) assure as equitable distribution of essential resources as possible, and (3) improve the measurement and understanding of how social determinants influence health.

1. What landmark investigation helped to focus attention on the role of social factors in determining health status?

A. The Framingham Study

B. The Whitehall Study

C. The British Doctors Study

D. The Nurses’ Health Study

2. Which of the following aspects of poverty is likely to contribute to health status?

A. Food security

B. Transportation

C. Adequate housing

D. All of the above

3. Population level health status has improved during the past century principally because of

A. a decline in cigarette smoking.

B. advances in pharmaceutical treatments.

C. enhanced social and economic resources.

D. improved management of acute care hospitalizations.

4. Psychological self-perception is thought to impact health through

A. stress from perceived inequalities.

B. loss of trust and social connections.

C. both A and B.

D. neither A nor B.

5. Social inequities during which of the following phases of life have the greatest impact on health outcomes?

A. The early childhood years

B. The adolescent years

C. The young adult years

D. The older adult years

6. What aspects of employment likely contribute to health status?

A. Poor working conditions

B. Temporary work

C. Lack of worker control

D. All of the above

7. Which of the following is NOT typically considered a social determinant of health?

A. Education

B. Social drinking

C. Transportation

D. Housing

8. Which of the following groups of workers is likely to have the lowest mortality rate?

A. Senior executives

B. Support staff

C. Skilled workers

D. Semi-skilled laborers

9. Which of the following countries has the highest levels of both income and health inequity?

A. Japan

B. United States

C. Canada

D. United Kingdom

10. Which of the following programs is likely to have the greatest impact on social determinants of health?

A. A physical fitness campaign

B. A healthy nutrition program

C. Early childhood education

D. Smoking cessation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree