![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the pharmacy student, community practice resident, or pharmacist should be able to:

1. Evaluate the individualized benefits and barriers for smokers who want to participate in a formalized smoking cessation program.

2. Assess OTC and prescription pharmacotherapy treatments that would be most successful for a particular smoker in his or her cessation attempt.

3. Develop individualized strategies for a smoking cessation attempt, including behavioral change, stress management, and pharmacotherapeutic factors.

4. Evaluate and overcome barriers in order to implement smoking cessation services within a community pharmacy or clinic.

5. Analyze the business management aspects needed to create and maintain smoking cessation services, such as recruitment, developing interdisciplinary support systems, and reimbursement issues.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Current estimates in 2012 show that approximately 45.3 million adults (19.3%) were smokers in the United States, including 21.5% men and 17.3% women.1 The prevalence has decreased slightly over the past several years. However, nicotine use still represents the single most preventable cause of premature death in the United States at over 440,000 people dying per year from smoking-related causes.1 This is one out of every five deaths due to smoking. Every year, smoking results in 5.6 million years of life lost prematurely and approximately 92 billion dollars of lost productivity. The amount of annual death in the United States resulting from smoking is more than that resulting from alcohol-related deaths, motor vehicle and gun accidents, homicides, and suicides combined. Indeed, the statistics are staggering!

The statistics regarding who in the population is most likely to smoke is interesting as well.1 Adults living below the poverty line are more likely to smoke than those living at or above the poverty line (28.9% versus 18.3% are smokers, respectively). Those with a GED diploma are more likely to smoke (45.2%), with 33.8% of those who have less than a high school education to consider themselves as “current” smokers. The most likely ages for smoking are adults between 25 and 44 years of age (22%), and American Indians and Alaskan Natives are the most likely ethnic groups who smoke (31.4%). Of interest, the 19.3% of Americans who smoke can be described as “regular” smokers, and greater than 80% of these smoke daily. Approximately 70% of polled smokers stated that they wanted to quit and have had at least one quit attempt in the past year.

BACKGROUND

BACKGROUND

The Impact of Nicotine Use

Approximately 8.6 million people in the United States have at least one serious smoking-related illness.2 Smokers most often die from lung cancer, but the second and third most likely cause of death for smokers is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and coronary artery disease (CAD), respectively. Smokers should be aware of the variety of cancers that can be caused by smoking. For example, cancer of the larynx, lip, tongue, esophagus, bladder, pancreas, kidney, cervix, and uterus are all associated with smoking.2Smoking increases the risk of death from COPD and is dependent on the number of cigarettes smoked daily. Fifteen percent and 25% of one and two pack per day smokers, respectively, are likely to be diagnosed with COPD. Smokers also should be aware of cardiovascular ramifications. Smoking increases the risk of death by three times for people with CAD.3 The blood pressure is raised for several hours after each cigarette. Smokers also die significantly earlier than nonsmokers—13.2 years for men and 14.5 years for women.2

Unfortunately, smoking-related mortality affects nonsmokers. Approximately 3000 nonsmokers die each year due to lung cancer. Secondhand smoke is associated with coronary heart disease as well. Kids and infants of smokers are the most affected by secondhand smoke. Secondhand smoke causes more than an estimated 202,000 asthma episodes, 790,000 cases of otitis media, and 430 sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) cases each year.2

How Nicotine Is Harmful?

Smokers know that it is harmful for them to continue, but specific knowledge about nicotine use is important. Cigarettes are full of harmful chemicals, including over 4000 chemical compounds and at least 40 known carcinogens.4 Some of these include ammonia, arsenic, carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, toluene, tar, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.4 Nicotine from smoking can reach the brain within 11 seconds and stimulates receptors in the ventral tegmental area.5 Next, dopamine is released in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex. Dopamine, as can be explained to patients, releases feelings of euphoria and pleasure and is often described as the “pleasure neurotransmitters.”6 Thus, the dopamine reward pathway is stimulated by “rewarding” experiences such as food, sex, and smoking, and these experiences become associated with increased dopamine release. Dopamine leaves the system rapidly as well, within minutes. The combination of rapid stimulation and exit with the dopamine reward pathway stimulates the need for repeat administration until tolerance develops.6

In addition to activation of dopamine receptors, nicotine results in the release of other neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine and acetylcholine. Increased norepinephrine release results in elevated heart rate, blood pressure, stroke volume, and cardiac output. This can lead to the cardiovascular problems mentioned. The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons can stimulate cytochrome P450 metabolism in the liver. This can expedite insulin metabolism and lead to increased insulin requirements for patients with diabetes. Smoking is especially harmful for patients with diabetes. Carbon monoxide of cigarettes also can interfere with the carbon dioxide/oxygen transmission in the alveoli of the lungs, leading to decreased oxygenation in the tissues of the lower extremities. Decreased peripheral vascular blood flow and increased risk of neuropathy can result. Also, high-density lipoproteins are decreased, while low-density lipoproteins are increased. Smoking can also lead to reduced estrogen levels, which can increase the risk of osteoporosis over time. Smokers know that “smoking is harmful”; however, a more thorough conversation regarding details by the health-care professional is often needed and appreciated.

Benefits of Cessation

Unfortunately, many smokers think that they will reap the benefits of cessation immediately. This is not the case for many of the consequences of smoking, so the time-course of experiencing benefits should be part of the discussion with them. After their quit date, many experience nicotine withdrawal in varying severity. If withdrawal is severe, they are likely to feel that the “cons” of quitting outweigh the “pros” (i.e., because they do not “feel better” immediately). For example, after 10 years of quitting, the risk of developing lung cancer has decreased to 50% of those continuing to smoke.7

In contrast, some benefits can be experienced more rapidly. For example, circulation improves and walking becomes easier within 2 weeks to 3 months after quitting. Lung function will increase up to 30%, and within 1—9 months lung cilia will begin to function normally again.7 Coughing, shortness of breath, and fatigue begin to decrease within this time period as well. Patients tend to not have to be hospitalized for minor infections as much. After 1 year, the risk of developing CAD decreases to half that of someone who has continued to smoke. The risk of being diagnosed with COPD decreases incrementally by year, and after 5 years the risk of stroke is reduced to the same as one who had never smoked. Smokers should also be reminded of other cessation benefits as well. They will feel better, look better, have more energy, and will have saved substantial money from quitting.

One particular drawback is weight gain after cessation. Most former smokers tend to gain a mean increase of 4 to 5 kg after 12 months of abstinence, with most weight gain within 3 months of quitting.8 Food begins to taste better and it is natural that their appetite increases. Former smokers would have to gain a substantial amount of weight—some sources discuss a 100-pound gain—before the benefits of smoking cessation would be offset by the weight gain.

Another common barrier for many older smokers is the preconceived idea that quitting would not benefit them. A study in the British Medical Journal examined the survival benefits of quitting.9 In this study, three different groups of physicians were followed between the years 1951 and 2001. The groups consisted of those who had never smoked, those who never stopped smoking over the course of their lifetime, and those who stopped at certain ages. The investigators found that if smokers stopped at age 30, they added 10 years to their lives and had a life expectancy similar to those who had never smoked. If they stopped at age 40, they lived an average of 9 years longer than the group who continued to smoke. If they stopped at ages 50 and 60, they lived an average of 6 and 3 years longer, respectively.9 A discussion of this study can address patients’ longevity questions, but the increased quality of life that they are likely to experience should also be stressed.

The Impact of Health-Care Providers

The Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline states that all clinicians should ask about tobacco use during every visit with patients.4 Smokers who receive assistance from physician clinicians are 2.2 times as likely to quit successfully for 5 or more months. Smokers are 1.7 times as likely to quit when receiving assistance from nonphysician clinicians in comparison to not receiving any assistance.4 Of interest, self-help material is no more effective for a smoker to quit and achieve abstinence for 5 or more months versus no other methods of assistance. Thus, the following methods of assisting smokers are not very effective by themselves: handing the smoker reading material about cessation, sending them to a Web site, and giving them a package insert for cessation medications without personally getting involved in the smoker’s quit attempt. The message is clear: smokers need assistance from health-care professionals through active methods of counseling.

Personal assistance given to the smoker for the quit attempt is important. The number of clinicians involved in the patient’s care is important as well. When smokers receive assistance in their quit attempt from two or more clinicians, they are 2.5 times as likely to quit for a sustained period of at least 5 months in comparison to smokers who receive no help from a clinician.4 Thus, the patient’s physician, nurse, and pharmacist should all be giving the smoker the same firm smoking cessation message.

While the smoker may not be interested in cessation during one particular visit to the pharmacy, patients tend to cycle through various stages of willingness to change their behavior. This will be explained in more detail later, but the pharmacist will have the perfect opportunity to effect this change at some point. Pharmacists can have a powerful role in smoking cessation. They are the most easily accessible health-care professionals, and over-the-counter (OTC) cessation products are very effective. Because the patient visits the pharmacy for refills either every month or every 3 months, the pharmacist could encounter the patient multiple times before another physician appointment.

Brief Clinical Interventions

Pharmacists should make brief clinical interventions for the following: (1) those who are willing to quit, (2) those who are unwilling to quit at the time of the discussion, and (3) smokers who have already quit.4 For those willing to quit, the pharmacist should be prepared to intervene effectively with the “Five A’s”:

![]() Ask—Systematically identify smokers at each visit, such as with new prescriptions. Also, the computer system could flag smokers when a prescription is picked up from the pharmacy.

Ask—Systematically identify smokers at each visit, such as with new prescriptions. Also, the computer system could flag smokers when a prescription is picked up from the pharmacy.

![]() Advise—A clear, strong, personalized message should be given to the smoker that cessation is the most important action to improve health. If the patient has asthma or COPD, the message should be tied in to these disease states. For example, one message given to the smoker picking up an inhaler for COPD could be this: “Mr. Smith, I see that you are picking up your inhaler refills. The inhalers can help you breathe better, but did you know that the only action that will extend your lifespan is to quit smoking?”

Advise—A clear, strong, personalized message should be given to the smoker that cessation is the most important action to improve health. If the patient has asthma or COPD, the message should be tied in to these disease states. For example, one message given to the smoker picking up an inhaler for COPD could be this: “Mr. Smith, I see that you are picking up your inhaler refills. The inhalers can help you breathe better, but did you know that the only action that will extend your lifespan is to quit smoking?”

![]() Assess—The pharmacist can ask, “Have you given any consideration to quitting smoking?” If the response is “yes,” the pharmacist could ask, “What time frame did you have in mind for quitting?” This assesses the smoker’s readiness to quit. If the patient responds, “within the next 6 months,” then the patient is likely in the contemplation stage of behavioral change (explained in the next section). If the patient responds, “within the next month,” the patient is considered to be in the preparation stage.

Assess—The pharmacist can ask, “Have you given any consideration to quitting smoking?” If the response is “yes,” the pharmacist could ask, “What time frame did you have in mind for quitting?” This assesses the smoker’s readiness to quit. If the patient responds, “within the next 6 months,” then the patient is likely in the contemplation stage of behavioral change (explained in the next section). If the patient responds, “within the next month,” the patient is considered to be in the preparation stage.

![]() Assist and Arrange—This chapter should adequately prepare the pharmacist to provide individualized counseling and assistance in a single or group setting. The pharmacist should arrange for follow-up within 1 week for the patient wanting to quit smoking.

Assist and Arrange—This chapter should adequately prepare the pharmacist to provide individualized counseling and assistance in a single or group setting. The pharmacist should arrange for follow-up within 1 week for the patient wanting to quit smoking.

Smokers who are unwilling to quit at the time it is first approached should not be “pushed” hard at first. At this point the patient usually is not ready to quit or even to begin talking about quitting. The best approach would be to state: “As your pharmacist, I would be glad to discuss smoking cessation with you at a later time when you are more ready.” The smoker will appreciate this straightforward approach and will be more likely to seek advice at a later date.

Finally, for those former smokers who have quit, the pharmacist should be supportive. Former smokers are proud that they were able to quit. Many even remember the exact date and time they smoked their last cigarette! Applaud the patient’s accomplishment, and be prepared if the patient gives any indication of relapse. If the patient is likely to relapse, information helpful for relapse prevention can be found later in this chapter.

IDENTIFYING STAGES OF BEHAVIORAL CHANGE AND LEVEL OF DEPENDENCE

IDENTIFYING STAGES OF BEHAVIORAL CHANGE AND LEVEL OF DEPENDENCE

Health-care providers of all types have been successful in helping smokers in the short term. Pharmacists are effective in asking, advising, and assessing smokers regarding a quit attempt. However, the health-care professions largely have not been as successful in the latter two components—assist and arrange. Smokers should be assisted with an individualized quit plan, and continuous follow up should be arranged. These are labor-intensive but essential for long-term success.

Transtheoretical Model of Behavioral Change

Smokers tend to cycle through stages ranging from “not considering quitting” to a “relapse” stage. This cycle has been linked to the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change.10 At any time, a smoker could be in one of the following components of this cycle: (1) not thinking about quitting and not ready to quit (precontemplation); (2) thinking about quitting and ready to quit, usually within the next 6 months (contemplation); (3) taking action to prepare for quitting, usually within the next month (preparation); (4) currently making a quit attempt (action); and (5) recently quit (maintenance). Unfortunately, many smokers experience relapse. Reasons include susceptibility to lingering psychologic dependence on nicotine and failure to implement permanent behavior changes. It is useful to identify in which stage of the Transtheoretical Model the smoker is in. Then, the pharmacist can gently urge the smoker toward the next stage. The Transtheoretical Model was discussed in the Motivational Interviewing chapter; thus, readers are referred to that chapter to review the stages as they apply to nicotine cessation and actions to take in each stage.

The Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence

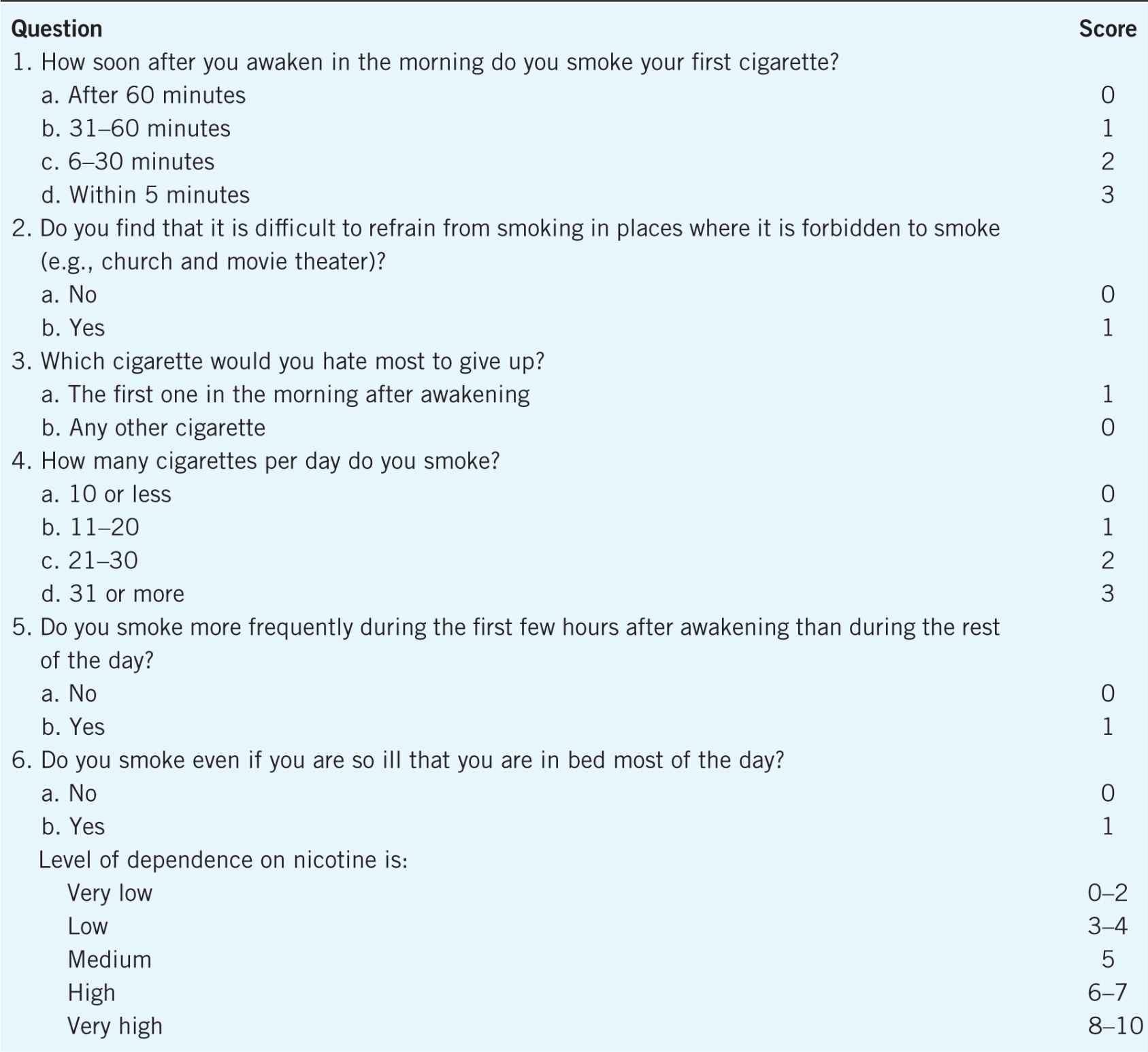

A powerful tool can be used to determine the level of nicotine dependence—the Fagerstrom Test.11 The test consists of six questions (Table 9–1), with an overall score of 0—10 to gauge the level of nicotine dependence. A common misconception is that the level of nicotine dependence is only correlated with the number of cigarettes that a smoker uses daily. A few may rate “high dependence” on this scale despite using relatively lower amounts of daily nicotine. The prudent pharmacist will consider all factors of the Fagerstrom Test when developing an individualized plan to quit.

Table 9–1. Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence

The Fagerstrom Test can also be used to discuss the differences between “habits” and “addiction”. Many smokers are steadfast that smoking is a “habit” and nicotine use can be stopped “anytime”. Higher scores on the Fagerstrom Test can be discussed in terms of the relationship between dependence and addiction. Patients tend to feel more comfortable when smoking is viewed as a “habit” rather than what it is—an addiction. By viewing nicotine use as an addiction, it may be easier for patients to implement the daily behavior changes needed for long-term success.

INITIAL COMPONENTS OF ASSISTING WITH A QUIT ATTEMPT

INITIAL COMPONENTS OF ASSISTING WITH A QUIT ATTEMPT

Several components to implement during a quit attempt include: establishing a quit date, an initial plan, practical counseling (past experience of tobacco use, quit attempts, and triggers), recommendation of pharmacotherapy, and discussion of social support.4 Further discussion should include behavioral modification, cognitive, and stress management strategies.

Basic Components

Many who try to stop smoking will not have a definitive strategy in place. Some will cut down on nicotine consumption until it “feels ready” to quit. With such a high recidivism rate associated with smoking, this is not a good plan. Patients should develop a definitive cessation plan and stick with it (with the pharmacist to assist them in developing the plan).

The Quit Date

The basic plan should begin with a decision regarding the “quit date.” This will be the first date that the patient will not smoke for the entire day. Some may try to link it to an important date, such as the patient’s birthday or the Great American Smokeout Day (sponsored by the American Cancer Society). It is best for the patient to choose the date, rather than have the whole class (if counseling in a group setting) stop on a specific date. The quit date should be a specific event. Encourage the smoker to circle it on the calendar and tell family and friends in anticipation of it. Of importance, the smoker should begin behavior modification strategies prior to the quit date. If the smoker does not follow through with this quit date, encourage the patient to set another as soon as possible before motivation is entirely lost. Each smoker’s journey to long-term cessation is unique, but it has to start somewhere!

Quitting By The START Plan

One good quit plan can be described as START: Set a quit date within the next couple of weeks, Tell everyone about the upcoming quit attempt, Anticipate problems, Remove tobacco products from the environment, and Take action. As setting a quit date has been discussed, smokers need to tell the spouse, family, friends, and coworkers, as appropriate, of this upcoming event. The smoker needs full cooperation from all for several weeks after the quit date. The patient needs to know that anyone who smokes will need to stay away during this crucial time period. A spouse will need to be especially understanding. A spouse who continues to smoke will need to go outside to smoke during this period. Having clean ashtrays and no access to cigarettes is important for the quit attempt as well. Any temptation during a “craving” due to nicotine withdrawal could lead one back to smoking. The spouse and family also will need to understand that mood changes could be experienced. A good way to enlist the help of the spouse would be to invite the spouse to join the smoker during cessation education.

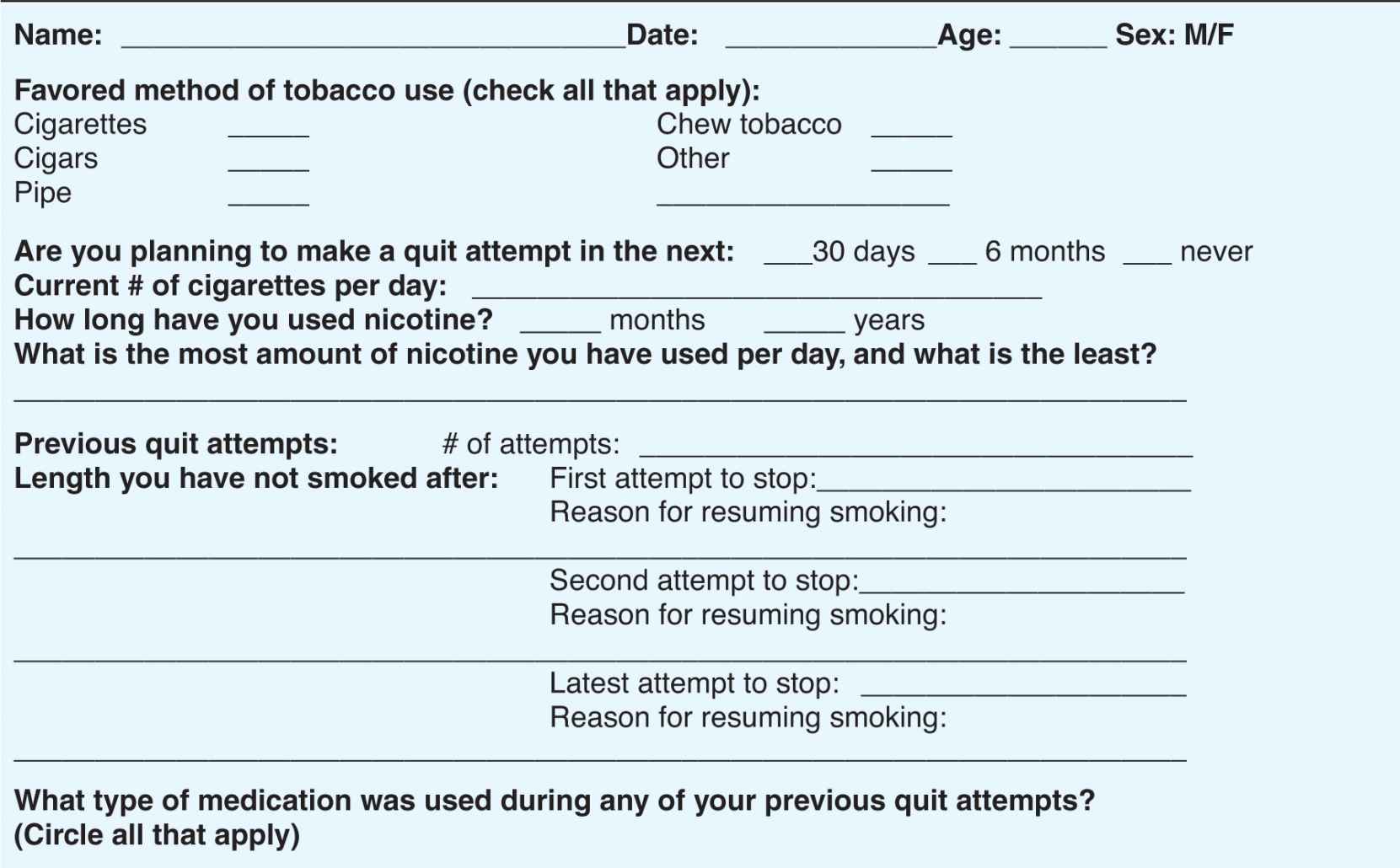

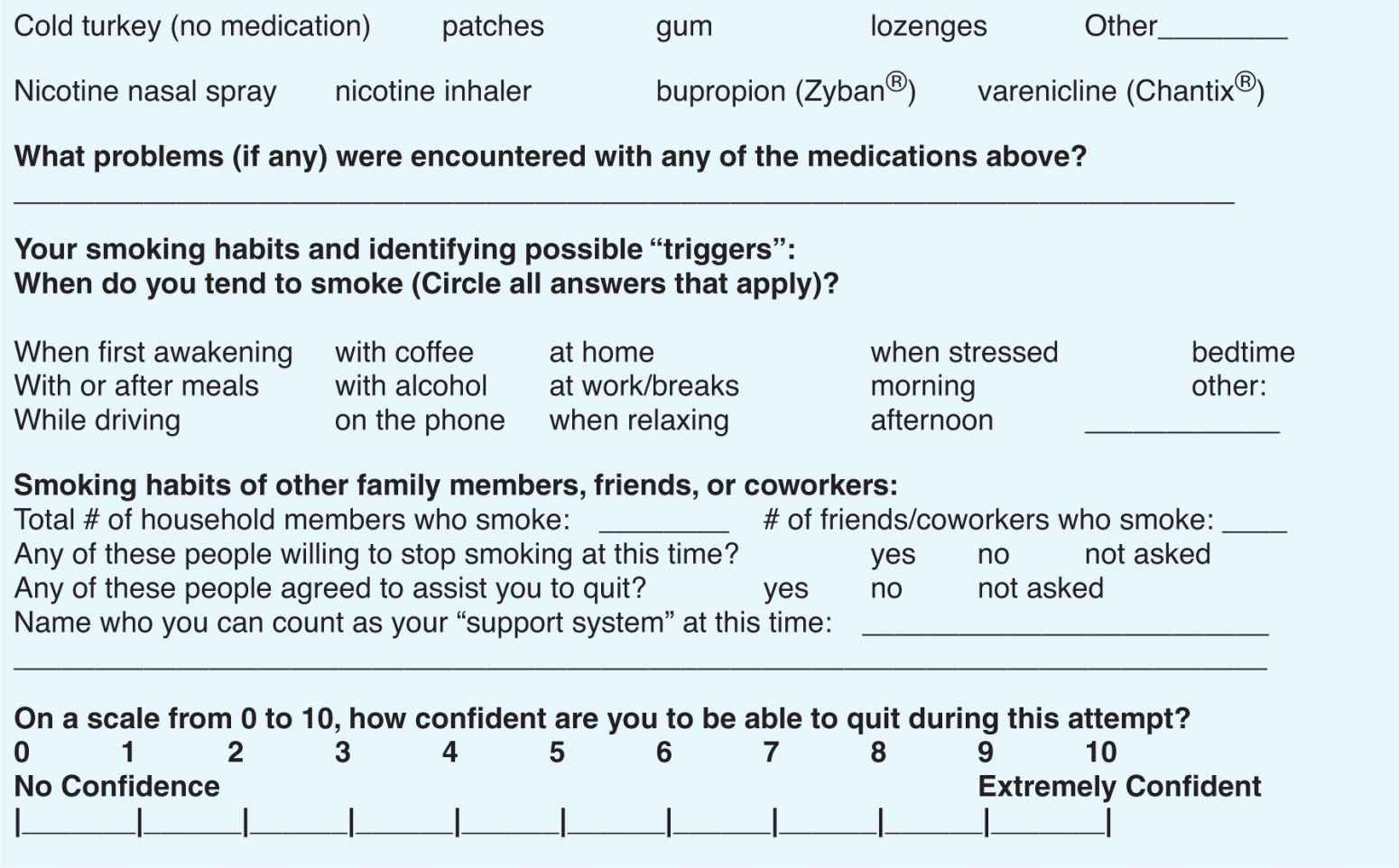

Obtaining a thorough history of nicotine use is essential prior to the quit attempt in order to anticipate problems. A thorough history of nicotine use would include obtaining the following: current daily use of nicotine, how many cigarettes (or cigars, etc.) have they smoked daily at the highest amount (and least amount) of nicotine use, total time length of nicotine use, brand(s) used, how many quit attempts have been tried (and success of attempts), past use of cessation medications, support systems in place, and triggers. An example documentation of nicotine use history can be found in Table 9–2. A frank discussion, in particular, of any previous quit attempts is important. Any problems that the smoker had with previous quit attempts will need to be resolved (or at least something different should be tried) to ensure success with the current quit attempt. For example, the pharmacist could discover that the previous quit attempt was unsuccessful because nicotine gum was not used appropriately. Also, this would be a good opportunity to discuss with the smoker that most people who are ultimately successful try to quit multiple times. The pharmacist could also add, “And for this quit attempt you are putting a plan into place before the actual quit date, so you are already way more likely to succeed.”

Table 9–2. Smoking History

Removing tobacco products from the smoker’s environment is important to limit quick access during the quit attempt. A few smokers balk at this idea, pointing out that a new pack of cigarettes could be purchased on the way home from work. Removing nicotine from the environment is strongly suggested due to the intensity and quick onset of cravings. Especially if it is the first attempt, the smoker may not be aware of how strong and fast a craving can occur. Also, if the patient does not have easy access, it would be a conscious decision for the patient to purchase a pack of cigarettes. The person hit with a craving on the way home from work would have to decide to stop at the store to purchase the cigarettes—and the patient is more likely to make the correct decision. Finally, the smoker preparing for the quit attempt should make sure that everything—ashtrays, lighters, and matches—associated with smoking is removed from the immediate environment.

Finally, the smoker must be willing to take action. Of all the most unhelpful behaviors, inaction is the worst. The smoker must be willing to put the individualized quit plan into action. In order to have the most success, the patient should be willing to begin making daily adjustments in behavior and thinking. If the smoker has not begun to take action after a couple of counseling sessions, the prudent pharmacist will focus on why—and perhaps use motivational interviewing techniques as a tool to explore the patient’s lack of motivation. The actions that the smoker can take, the small steps, prior to the quit attempt will pay dividends down the road.

Behavioral Modification Strategies

Recognizing and Preventing Triggers

Behavioral modification strategies should begin prior to the quit date. This point cannot be overemphasized, because many unsuccessful quit attempts are initiated without implementing changes in daily behavior. Patients should recognize “triggers” and should be prepared to combat them during the quit attempt.4 Although triggers are highly individualized, common ones include the tendency to smoke first thing in the morning after awakening, while drinking coffee or alcohol, after meals, while “relaxing” in front of the television, and while traveling in a vehicle.

The pharmacist should help the smoker initiate daily substitutes for smoking triggers—often called stimulus control methods. These substitutes can include taking long walks when the triggers occur, getting busy with projects such as washing dishes or doing other chores around the house, or working on long-term projects such as painting a room. Deep breathing and visualization are good stress management techniques that will be explained in more detail later.

Self-Observation

Self-observation is another useful tool prior to the quit attempt. For example, patients with diabetes or hypertension keep daily records of blood glucose or blood pressure levels, respectively. Record keeping is helpful for both the patient and the clinician. The smoker should keep a daily record, including what time of the day each cigarette was smoked, what (if anything) triggered the event, and the patient’s mood (e.g., stressed or depressed). Many smokers who record nicotine use are surprised at the actual amount smoked. A “one-pack-per-day” smoker may in reality be smoking two packs per day! This recording gives the patient great insight into what triggers nicotine use, when the triggers occur, and what time of day most nicotine use occurs. The pharmacist should help the patient develop a plan to combat each of those times. Those will be the times when the strongest nicotine withdrawal (i.e., cravings) will be experienced.

Practical Changes to Implement

Self-observation can give the smoker insight as to what practical behavior changes need to be implemented prior to the quit date. Fewer than 5% of people who quit without assistance are successful for longer than a year. This underscores the fact that few smokers adequately prepare and plan for the quit attempt. The pharmacist should discuss that this is a process that starts weeks prior to the quit attempt, when the patient starts forming better habits to last through the attempt and beyond.

One of the first steps in changing behavior is to recognize the times one smokes “automatically.” Many smoke during times of stress without even being aware of the nicotine use. Stress management techniques will be discussed in the next section, but patients smoke “automatically” at other times, too. If the patient smokes while drinking coffee, driving, or at a bar with friends, some suggestions for combating these triggers are given in Table 9–3.

Table 9–3. Suggestions for Combating Triggers and Making Behavioral Changes

The changes discussed in Table 9–3 to combat triggers should be made prior to the quit date. As some of these points involve “switching” suggest that the smoker switches the brand of cigarette. Many smokers balk at this because it is likely that one brand is prized above all others. When switching brands, the patient could try one with less nicotine (but remember: there is no such thing as a “safe” level of nicotine) or “light” cigarettes. Switching brands makes it a little easier for some because the patient has already “given up” a particular brand.

When preparing for the quit date, the smoker should be aware of each time nicotine is used. For example, the smoker should never buy another carton of cigarettes. Buying cigarettes by the carton makes it tougher to quit. The patient should begin purchasing only single packs weeks before the quit date. That way, every time another pack of cigarettes is purchased, the patient is making a conscious decision to continue smoking until the pre-set quit date.

Many smokers view smoking as an enjoyable activity, so this should be reversed. The smoker should no longer smoke when watching television, relaxing, or doing any enjoyable activity. Suggest that the patient only go outside to smoke, or smoke in a dark room (preferably a closet) or while facing a corner of the house. The patient should smoke the cigarette and then return to an enjoyable activity. To expand on this idea, have the smoker not clean up the ashtrays in the house for several weeks. As an alternative, cigarette butts could be placed into an empty milk container. Later, during the quit date and beyond, whenever the cravings are strong, the patient could pull out this foul-smelling milk container, uncap it, and take a whiff.

The patient also should attempt to taper nicotine use. A good general goal for tapering would be to decrease the nicotine use by one-half each week prior to the quit date. For example, a two-pack per day smoker could start a month prior to the quit date, and cut down to one pack per day. The next week, the patient could start at one-half pack, and so forth. Thus, even a two-pack per day smoker could have decreased the nicotine use from 40 cigarettes per day (two packs) to 2 or 3 cigarettes per day prior to the quit date. The only caveat to this is that the patient should have set the quit date beforehand.

THE QUIT DATE AND BEYOND

THE QUIT DATE AND BEYOND

The quit date is the patient’s pre-determined date for smoking cessation. For those using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), the medications should be started on this date. If using bupropion or varenicline, those medicines should have been started 1—2 weeks prior to the quit date.4 The behavior changes previously implemented should still be followed. The patient should be prepared for intense cravings, usually experienced at heightened times of nicotine use throughout the day. An especially strong craving may be experienced upon awakening. Some “hints” to assist the patient during the first day of the quit date can be found in Table 9–4. In addition, the patient should have a plan in place to handle the effects of nicotine withdrawal.

Table 9–4. Suggestions for the Quit Date