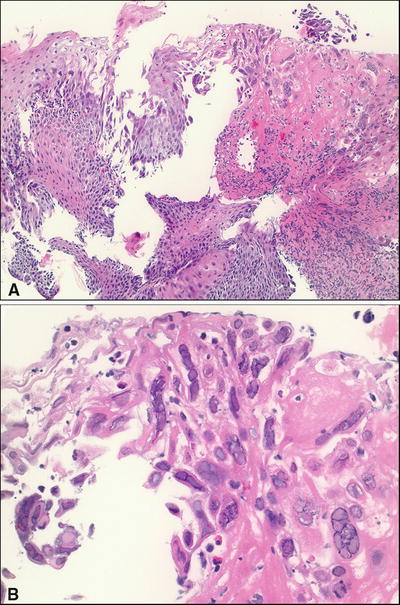

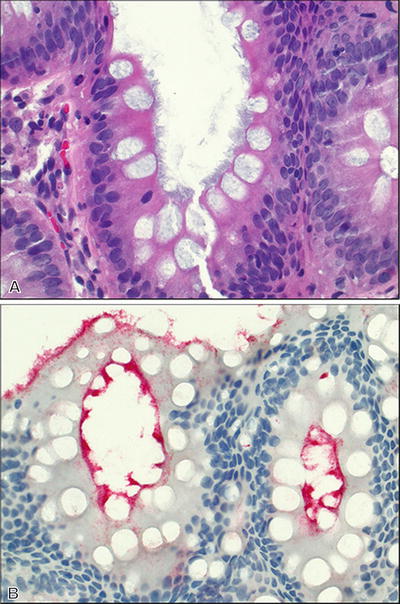

Fig. 42.1.

Cytomegalovirus infection.

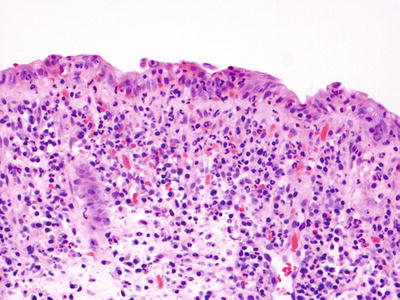

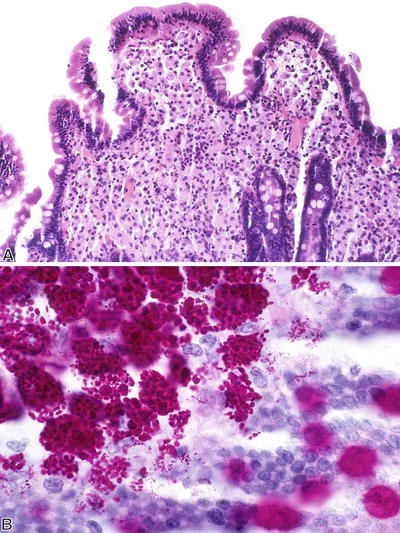

Fig. 42.2.

Herpes simplex virus infection, esophagus. (A) Low and (B) high magnification.

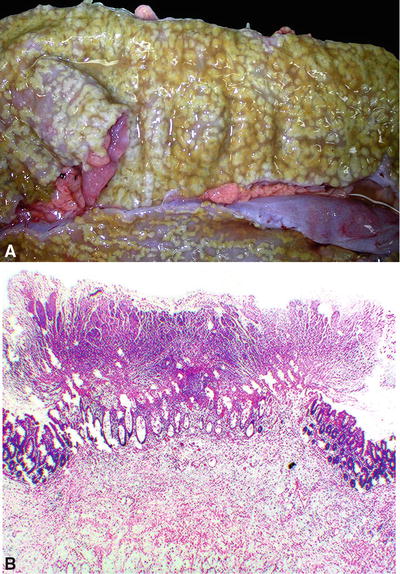

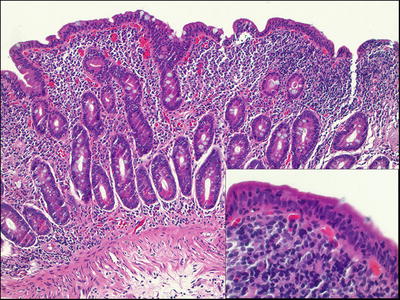

Acute Bacterial Enterocolitis (Fig. 42.3 )

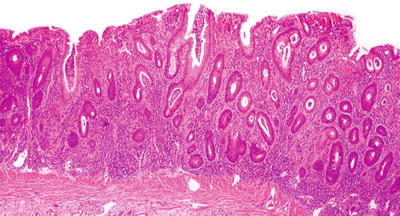

Fig. 42.3.

Acute infectious enterocolitis.

Clinical

♦

Acute onset of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody diarrhea

♦

Symptoms are short lived or self-limited

♦

Stool cultures are negative in half of the cases

♦

Common pathogens: Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, and Escherichia coli

Macroscopic

♦

Patchy, extremely variable mucosal erythema, inflammation, and erosion

Microscopic

♦

Extremely variable

♦

Mild mucosal edema, congestion, and nonspecific chronic inflammation

♦

Neutrophils within superficial lamina propria and crypts

♦

No chronic mucosal architectural damage

♦

No basal lymphoplasmacytosis

Specific Bacterial Infections

Vibrio Cholerae

♦

Causes cholera, a significant cause of watery diarrhea with dehydration and even death worldwide

♦

Unremarkable histology with no or minimal inflammation

♦

Reactive changes such as mucin depletion may be seen

Shigella

♦

Causes severe watery or bloody diarrhea

♦

Almost always involves rectosigmoid colon with variable proximal extension; the ileum may be involved

♦

Indistinguishable from other enteric infections

♦

Purulent lamina propria in severe disease, with cryptitis, crypt abscesses, and pseudomembranes

♦

Usually associated with lymphoid follicles with formation of aphthous ulcers (may mimic Crohn disease)

♦

May resolve to an atrophic mucosa, mimicking inactive ulcerative colitis

Salmonella

♦

Important cause of food poisoning and traveler’s diarrhea

♦

Many species (typhoid and nontyphoid)

♦

Erythematous, friable mucosa, preferentially in proximal colon

♦

Rectum also frequently involved

♦

Similar histopathology to other enteric infections (nontyphoid species)

♦

Typhoid fever may cause bowel wall thickening, primarily in the right colon and ileum with formation of aphthous, deep, and/or linear ulcers; may mimic Crohn disease

Campylobacter

♦

Numerous species

♦

Infections associated with undercooked poultry, unpasteurized milk, and contaminated water

♦

Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea (sometimes bloody), and fever

♦

Indistinguishable from other enteric infections

♦

Can mimic inflammatory bowel disease

Yersinia

♦

Two species

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis

Yersinia enterocolitica

♦

Cause acute terminal ileitis, appendicitis, and colitis

♦

Markedly thickened terminal ileum with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes

♦

Necrotizing granulomas with central necrosis, neutrophilic infiltrate, and peripheral palisading histiocytes in the background of dense lymphocytic infiltration, mimicking Crohn disease

Aeromonas

♦

Caused by ingestion of contaminated water, produce, meat, or dairy products

♦

Typically causes mild diarrhea that is self-limited but more severe illness can occur

♦

Similar histopathology to other enteric infections

♦

In severe and chronic cases, architectural distortion may be present, closely mimicking inflammatory bowel disease

♦

Associated with prior antibiotic exposure

♦

Most common in hospitals and nursing homes

♦

Cramping, abdominal pain, profuse diarrhea, and fever a few days or weeks after use of antibiotics

♦

Affects entire colon, but most severe in the distal colorectum and may affect the distal small bowel

♦

Classically causes pseudomembranous colitis which may be diffuse or patchy

♦

Mushroom or volcano-like exudate of neutrophils, mucin, and necrotic epithelium from superficial crypt lumen with relatively intact basal crypt

♦

Diffuse lamina propria neutrophilic infiltration and edema

♦

Other causes of pseudomembranous colitis include other organisms (e.g., verotoxin-producing E. coli) and ischemia (ischemic colitis)

♦

Transmitted via contaminated meat (most common), water, milk, produce, and person-to-person

♦

Diffuse edematous and friable mucosa with patchy hemorrhagic erosions

♦

Similar to other infectious colitis plus features of acute ischemia

♦

Hemolytic uremic syndrome or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura may develop

Fig. 42.4.

Pseudomembranous colitis. (A) Gross and (B) microscopic.

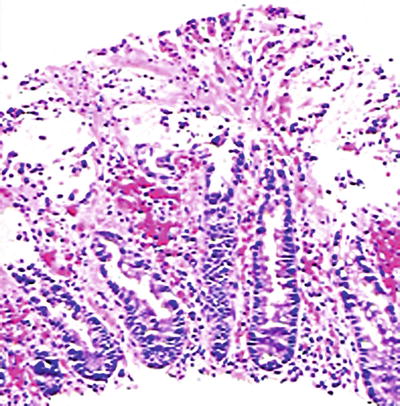

Fig. 42.5

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (O157:H7).

Parasitic Infections

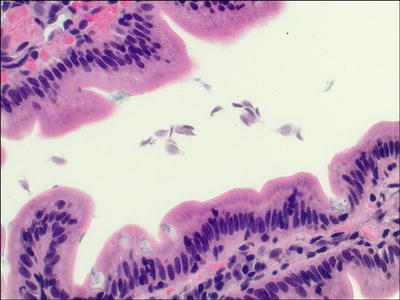

Giardiasis (Fig. 42.6 )

Fig. 42.6.

Giardiasis.

♦

Most commonly reported parasitic disease in the USA and Canada

♦

Usually waterborne, where cysts are ingested, can also be fecal–oral, and from food contamination

♦

Clinical presentation varies from asymptomatic to chronic diarrhea (giardiasis), usually 5–7 days of explosive, foul-smelling, watery diarrhea

♦

Cysts are ingested, and then trophozoites colonize the proximal 25% of the intestines

♦

Characteristic pear-shaped, binucleate, gray, or faintly basophilic organisms seen adherent to surface epithelium and between villi, in otherwise normal mucosa

♦

Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes may be present

Amebiasis

♦

Infection by Entamoeba histolytica

♦

Usually asymptomatic, but may present with severe, fulminant colitis

♦

Cecum and right colon are most often involved

♦

Colon may appear normal or may contain small or large, coalescing ulcers

♦

Histologically, the ulcers are nondescript with neutrophilic inflammation (if a resection is performed, the ulcers may have a flask-shaped appearance)

♦

Organisms are usually present within the exudate and resemble foamy histiocytes; the presence of red blood cells within the cytoplasm is helpful

♦

Normal intervening mucosa

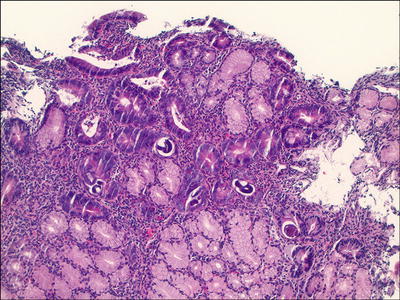

Strongyloides Stercoralis (Fig. 42.7 )

Fig. 42.7.

Strongyloides, duodenum.

♦

Affects immunocompromised people

♦

Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss

♦

Female lives and lays eggs in the small intestine

♦

Endoscopically, ulcers or enlarged folds may be seen in the stomach, small bowel, and colon

♦

Histologically, worms and larvae may be seen within crypts or glands, and there may be associated edema, eosinophilia, neutrophilia, villous blunting, and ulceration, with or without granulomas

Pinworm

♦

Caused by Enterobius vermicularis, one of the most common human parasites

♦

Transmission by fecal–oral route

♦

Worms reside in the ileum, proximal colon, and appendix

♦

Female migrates to anus to lay eggs; causes the symptom of anal pruritus

♦

May be detected on colonoscopy or in appendectomy specimens

♦

Worms are 2–5 mm in length and typically do not incite a tissue reaction

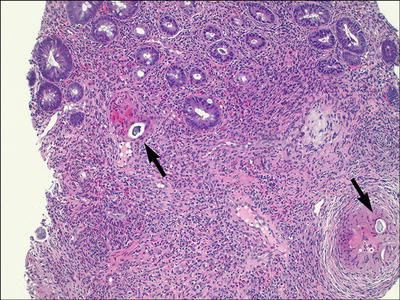

Schistosomiasis (Figs. 42.8 and 42.9 )

Fig. 42.8.

Schistosomiasis, colon. Active eosinophilic and granulomatous inflammation with foreign bodies (eggs).

Fig. 42.9.

Schistosomiasis, appendix. Calcified eggs.

♦

Endemic in Africa, Asia, and South America

♦

Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, S. mekongi, and S. intercalatum can infect any/all parts of the GI tract

♦

Symptoms typically include bloody diarrhea, anemia, and weight loss

♦

Endoscopically, mucosal erythema, granularity, and even polypoid lesions may be noted

♦

Histologically, granulomatous and eosinophilic inflammation is present early, followed by fibrosis

♦

Eggs may be seen within the granulomas or may appear as round-to-oval calcified bodies

Other Infections

Intestinal Spirochetosis (Fig. 42.10 )

Fig. 42.10.

Intestinal spirochetosis. (A) H&E and (B) T. pallidum immunostain.

Clinical

♦

Majority represents a commensal relationship with host with no associated symptoms or disease

♦

May affect immunocompetent or immunocompromised people

♦

Small minority may develop pathogenicity and become invasive leading to enterocolitis, hepatitis, and bacteremia:

Due to augmented virulence of the organisms

Due to reduced host defense

♦

Two main organisms:

Brachyspira aalborgi

Brachyspira pilosicoli

♦

Metronidazole effective therapy

Macroscopic

♦

Almost always normal

Microscopic

♦

A continuous fuzzy blue-gray band primarily located on the epithelial surface of the colon

♦

Normal colonic architecture with minimal inflammation

♦

Highlighted by Warthin–Starry or Steiner stains; while not the same organisms, the T. pallidum immunohistochemical stain will highlight intestinal spiroch etes

Treponema Pallidum

Clinical

♦

Syphilis can affect the gastrointestinal tract, predominantly the anorectum (anal squamous mucosa or rectal mucosa) but also other sites (luetic gastritis)

♦

Often asymptomatic

♦

May present with anal pain or upper GI bleeding

Macroscopic

♦

Anal chancres

♦

Mucocutaneous rash, masses, condyloma lata

♦

Gastritis and gastric ulcers

Microscopic

♦

Characterized by a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the rectal or gastric lamina propria or anal soft tissue

♦

Acute inflammation may be present

♦

Immunohistochemistry for T. pallidum is useful; silver stains such as Warthin–Starry or Steiner can also be used

Whipple Disease (Fig. 42.11 )

Fig. 42.11.

Whipple disease. (A) H&E and (B) PAS with diastase.

Clinical

♦

Rare, a systemic infectious disease often diagnosed on small bowel biopsies

♦

Caused by Tropheryma whippelii

♦

M > F

♦

Fever, weight loss, polyarthralgia, diarrhea, and central nervous system (CNS) symptoms

Macroscopic

♦

Primarily involves the small bowel

♦

Edematous and thickened intestinal wall with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes

♦

Club-shaped villi show white–yellow appearance

Microscopic

♦

Villous blunting and distention

♦

Foamy macrophages in lamina propria

♦

Rodlike intracellular organisms strongly positive on periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase stain

♦

Polyme rase chain reaction (PCR) specifically identifies the bacterial genome

Malabsorptive Disorders

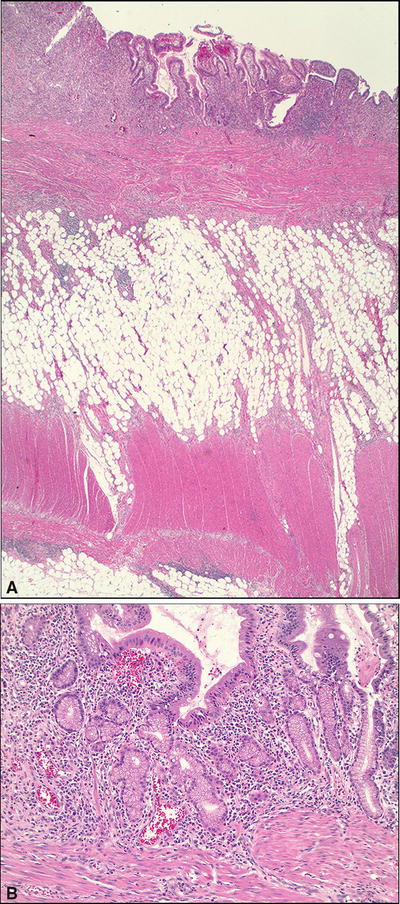

Celiac Disease (Fig. 42.12 )

Fig. 42.12

Celiac disease.

Clinical

♦

Affects 1.0% of healthy Americans, both children and adults.

♦

Strong family clustering: 10% prevalence among first-degree relatives, 30% in human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical siblings, and 70% in identical twins

♦

Strong association with HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8

♦

Small intestinal epithelial injury caused by dietary wheat gluten (and particularly, its alcohol-soluble fraction, gliadin)

♦

Variable presentation from minor nutritional deficiencies to more severe steatorrhea, malnutrition, and weight loss.

♦

Circulating antigliadin, antiendomysial, and tissue transglutaminase antibodies in >90% of the untreated patients.

♦

Increased risk for malignancy (small intestinal T-cell lymphoma and adenocarcinoma).

♦

Diagnosis relies on clinicopathologic findings including typical symptoms, positive celiac disease autoantibodies, and supportive histopathology.

Macroscopic

♦

Changes may be subtle but flat mucosa with scalloped folds may be seen.

♦

Most commonly involves the proximal small bowel.

♦

Ileum appears normal or minimally affected.

Microscopic

♦

Nonspecific and variable but supportive in the proper clinical context and with positive serology.

♦

Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes.

♦

Should be pre sent along the edges of the villi and importantly at the villous tips.

♦

May be the only finding.

♦

Immunostain for CD3 can highlight the increase in equivocal cases

♦

Should report increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes even in the absence of villous blunting

♦

Villous blunting from mild to completely flat mucosa

♦

Cuboidal or flattened surface epithelium with loss of goblet cells

♦

Crypt hyperplasia with increased crypt epithelial mitoses

♦

Dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in lamina propria

♦

In latent or occult celiac disease, intact villi or partial villous blunting and mild, patchy changes as mentioned above

♦

May be associated with lymphocytic colitis and/or lymphocytic gastritis

♦

Mucosal architecture restores quickly following a gluten-free diet along with a dramatic improvement of clinical symptoms

♦

Differential diagnosis, especially with intact villi or partial villous blunting, includes bacterial overgrowth, medication-induced inflammation (such as from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications), some fo od allergies, systemic autoimmune disorders, and lactose intolerance

Variants/Complications

♦

Latent celiac sprue

Asymptomatic or with skin manifestations (dermatitis herpetiformis)

Become symptomatic following an intestinal viral infection or high-gluten diet

No or mild villous blunting of the duodenal mucosa with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes

♦

Refractory celiac sprue

Uncommon, may be de novo or initially responsive to a gluten-free diet

Relapse while on gluten-free diet; only responsive to corticosteroids

Persistent flat mucosal lesion

Infiltrating T cells tend to be monoclonal, suggesting this is a neoplastic disorder

Poor prognosis with relentless and progressive malabsorption

♦

Ulcerative jejunitis

A rare condition in the sixth or seventh decades of life with a poor prognosis

Unknown pathogenesis; patients may have a refractory celiac sprue

Multiple mucosal ulcers in the jejunoileum

Infiltrating T cells tend to be monoclonal, suggesting this is a neoplastic disorder

May be associated with intestinal T-cell lymphoma (enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma), which typically forms the base of the ulceration

Nonresponsive to a gluten-free diet

♦

Collagenous sprue

May be a component of refractory sprue

May lack autoantibodies and hence a form of unclassified sprue

Typical mucosal changes of celiac sprue with thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer

May or may not respond to a gluten-free diet

Common Variable Immunodeficiency ( CVID ) (Fig. 42.13 )

Fig. 42.13.

Common variable immunodeficiency. (A) Low and (B) high magnification.

♦

The most commonly diagnosed primary immunodeficiency.

♦

Defined clinically by recurrent infections and hypogammaglobulinemia (a reduction in IgG and at least one other immunoglobulin isotype) and failure to respond to a vaccination challenge

♦

GI tract involvement can mimic celiac disease, Crohn disease, acute graft-versus-host disease, and lymphocytic colitis

♦

Plasma cells are typically absent in CVID, while they are usually increased in the other processes in the differential diagnosis

♦

Plasma cells can be present in some cases.

Tropical Sprue

♦

A malabsorptive syndrome associated with small bowel abnormalities

♦

Occurs in tropical regions in the world

♦

Unclear pathogenesis, environmental factors (especially intestinal microbial flora and enterotoxin production)

♦

Flat mucosal lesion throughout the small intestine

♦

Similar histopathology to celiac disease but intraepithelial lymphocytes more prominent within crypts and complete villous atrophy is uncommon

♦

Responsive to antibiotics, not to a gluten-free diet

Idiopathic Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Ulcerative Colitis ( UC ) (Figs. 42.14 and 42.15 )

Fig. 42.14

Ulcerative colitis (gross).

Fig. 42.15

Ulcerative colitis (microscopic).

Clinical

♦

One of the two major forms of inflammatory bowel disease (the other is Crohn disease)

♦

Incidence of 10–12/100,000; F slightly > M; Caucasians > African Americans

♦

Bimodal age of onset: 15–25 years (larger peak) and 55–65 years

♦

Etiology is unknown

♦

Family history is associated with increased risk

♦

Symptoms include: rectal bleeding, frequent stools, rectal mucous discharge, abdominal pain

Macroscopic

♦

Involves the rectu m with variable proximal spread in a continuous fashion

♦

No intervening areas of uninvolved mucosa in untreated cases

♦

The terminal ileum can be involved (“backwash ileitis”) in ulcerative pancolitis cases

♦

Active phase

Mucosa appears hyperemic and granular with inconspicuous or multiple punctate ulcers

When severe, the ulcers have “tramline”-like appearance

Nonulcerated mucosa often appears polypoi d

♦

Fulminant phase

Toxic megacolon may occur where the bowel is markedly dilated and thin-walled with diffusely congested and grossly ulcerated mucosa

Perforation may occur

♦

Quiescent phase

Featureless atrophic mucosa

Shortened colon with decreased caliber and thickening of the muscularis propria

Microscopic

♦

Inflammation exclusively confined to the mucosa in the nonulcerated areas, may extend deep in the submucosa to abut the muscularis propria in ulcerated areas

♦

Transmural chronic inflammation with lymphoid aggregates should not be present

♦

Active phase

Diffuse cryptitis, crypt abscesses

Dense mixed lamina propria inflammation (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils)

Evidence of chronic mucosal injury: dense basal lymphoplasmacytosis (with gland foreshortening), crypt distortion (deep crypt branching), Paneth cell metaplasia in the left colon/rectum

♦

Fulminant phase

Entire mucosal surface may be ulcerated

Often indistinguishable from other causes of fulminant colitis such as ischemic colitis, severe infectious colitis, or Crohn disease

♦

Quiescent phase

Lack of cryptitis and crypt abscess

Mucosal architectural abnormali ties with mild crypt distortion

Basal lymphoplasmacytosis

Paneth cell metaplasia

Mucosal atrophy

♦

Patchy inflammation may be noted after therapy

♦

Multinucleated giant cells can be seen due to histiocytic response to the ruptured crypts; true noncaseating epithelioid granulomas are not seen

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Crohn disease

Involvement of terminal ileum (more than “backwash ileitis”)

Skip lesions

Focally intense cryptitis

Aphthoid lesions

Epithelioid granulomas

♦

Infectious (bacterial) colitis

Superficial neutro philic infiltrate

Preservation of mucosal architecture

No basal lymphoplasmacytosis

♦

Lymphocytic colitis/collagenous colitis

Intraepithelial lymphocytosis

Subepithelial collagen table thickening in collagenous colitis

Cuboidal or flat surface epithelium

Lack of mucosal architectural distortion

♦

Ischemic colitis

Mucosal collapse

Lamina propria edema and hemorrhage with or without neutrophilic infiltrate

Injured crypts (microcrypts) and crypt dropout

Lamina propria hyalinization (fibrosis)

♦

Drug-induced colitis and proctitis

Can mimic ulcerative colitis but not typically as diffuse or severe

Usually no to mild mucosal architectural distortion

May have increased epithelial apoptosis

May also mimic ischemic injury

Seen with medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Drug history required for the evaluation

Associated Conditions

♦

Ulcerative colitis-associated epithelial dysplasia

Incidence increases over the duration of the disease

Risk is highest with ulcerative pancolitis

Can occur anywhere in the colon as patchy flat or slightly raised mucosal lesions

May be focal and often inconspicuous

Systematic, multiple mucosal biopsies increase the chance of detection

Histologically similar to sporadic colonic adenomas

Two grades: low- or high-grade dysplasia based on both architectural and cytological abnormalities (if uncertain due to inflammation and reactive atypia, use “indefinite for dysplasia”)

Low-grade dysplasia may regress or progress to higher grade

High-grade dysplasia may coexist with or progress to adenocarcinoma

♦

Adenocarcinoma

Develops in 3–5% of patients with UC

Risk increases with duration of disease

Preceded by epithelial dysplasia

Any stricture in UC should be concerning for malignancy

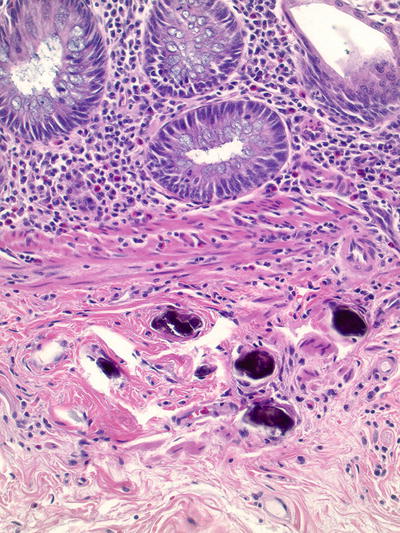

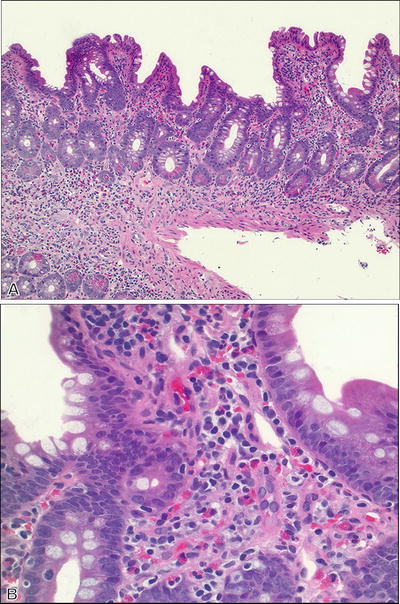

Crohn Disease (Fig. 42.16 )

Fig. 42.16.

Crohn disease. (A) Low and (B) high magnification.

Clinical

♦

One of the two major forms of inflammatory bowel disease (the other is UC)

♦

Incidence of 3–10/100,000 and is increasing

♦

M:F = 1:1

♦

Bimodal: one-third presents before age of 20, one-fifth presents after age of 50

♦

Etiology unknown, but strong genetic predisposition; increased risk with family history

♦

Symptoms include:

Chronic or nocturnal diarrhea

Intermittent right lower-quadrant intra-abdominal pain

Anorexia, weight loss, and fever

Recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations, perianal fissures , fistulae, or abscesses

Extraintestinal manifestations affecting the skin, eyes, and joints

♦

Complications include small bowel obstruction, malabsorption, salpingitis, fistulae, and perianal abscess formation

Macroscopic

♦

Inflammation anywhere from mouth to anus

♦

Most with lesions of small and large intestines

Small intestine only (30–40%), particularly the terminal ileum

Both small and large intestines (40–50%)

Colorectum alone (15–25%)

♦

Colonosco py

Mucosal cobblestoning, aphthoid or longitudinal ulcers, strictures

Normal intervening mucosa (skip lesions)

♦

Resected specimen

Markedly thickened bowel wall with luminal narrowing

Mucosal cobblestoning, pseudopolyps

Fat wrapping of the serosal surface.

Fissures, fistulae, and mesenteric abscesses may also be seen

Microscopic

♦

Transmural inflammation with multiple lymphoid aggregates

♦

Aphthoid and fissuring ulcers

♦

Focally intense cryptitis, crypt abscesses

♦

Skipped, normal intervening mucosa

♦

Focal/mild to moderate crypt distortion and basal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates

♦

Paneth cell metaplasia

♦

Pyloric gland metaplasia

♦

Neural hyperplasia, submucosal fibrosis, and hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosae

♦

Noncaseating epithelioid granulomas (in 25–50%)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Ulcerative colitis

See above

♦

Ischemic enterocolitis

No epithelioid granulomas

Lack transmural lymphoid aggregates, neural hyperplasia, or fissuring ulcer

May be difficult to distinguish a low-grade ischemic colitis in elderly patients from Crohn disease; subsequent clinical course may provide better differentiat ion

♦

Infectious colitis

Most common cause of aphthous ulcers of the small and large intestine

Diffuse superficial neutrophilic infiltrates

Lack significant chronic inflammation

Absence of crypt distortion or basal lymphoplasmacytosis

No epithelioid granulomas

♦

Diverticular disease-associated segmental colitis

Commonly seen in sigmoid colon

Diverticula per colonoscopy

Histologic changes may be very similar to those of Crohn disease

Foreign body type granulomas

♦

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS)/mucosal prolapse change

Usually seen in the rectum and distal sigmoid

Polypoid, nodular, or mass-like lesion

Intramucosal smooth muscle proliferation on histology

Normal adjacent flat mucosa and proximal colon

♦

Gastrointestinal tuberculosis (TB)

Very rare

Granuloma with central caseous necrosis

Travel to or residential history in areas where abdominal TB is common

♦

Yersinia enterocolitica

Necrotizing granulomas within the lymphoid follicle of the bowel wall and mesenteric lymph nodes

Positive Yersinia serology with rising antibody titer

Associated Conditions

♦

Crohn colitis-associated epithelial dysplasia

Similar to ulcerative colitis-associated epithelial dysplasia at slightly lower incidence

Malignancy in Crohn disease

♦

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type

♦

Metachronous or synchronous tumors may occur

♦

May be preceded by detectable epithelial dysplasia

Microscopic Colitis

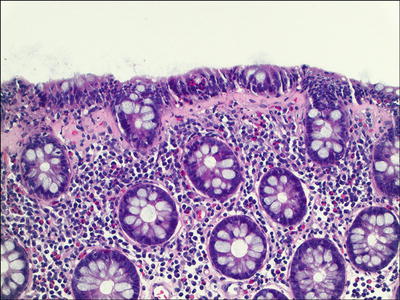

Lymphocytic Colitis (Fig. 42.17 )

Fig. 42.17.

Lymphocytic colitis.

Clinical

♦

Affects all ages but often people over 40 years, M = F

♦

Unknown etiology

♦

Prolonged watery diarrhea

♦

Associated with autoimmune diseases (celiac sprue, arthritis, and thyroiditis)

Macroscopic

♦

Normal colonoscopic and radiographic examinations (hence the clinical term “microscopic colitis”)

Microscopic

♦

A marked increase of lymphocytes in the surface and crypt epithelium

♦

Chronic inflammation in the lamina propria

♦

Cuboidal and flattened surface epithelium

♦

Absence of a thickened subepithelial collagen layer

♦

No crypt distortion

♦

Acute cryptitis may be seen

♦

Differential diagnosis includes medication-related inflammation (such as from NSAIDs) and colonic involvement by celiac disease

Collagenous Colitis (Fig. 42.18 )

Fig. 42.18.

Collagenous colitis.

Clinical

♦

Affects middle-aged and older women, F:M = 10–20:1

♦

Unknown causes

♦

Protracted watery diarrhea without systemic symptoms

Macroscopic

♦

Normal colonoscopic and radiographic examinations (hence the clinical term “microscopic colitis”)

Microscopic

♦

Proximal colon is more affected

♦

Thickened subepithelial collagen layer (usually >10 μm; normal, 2–3 μm) with irregular interface with lamina propria; cellular elements (endothelial cells, inflammatory cells) are incorporated into the fibrosis

♦

Subepithelial collagen layer thickening can be variable/patchy

♦

Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes and often eosinophils.

♦

Surface epithelial damage and sometimes artifactual detachment of the surface epithelial lining

♦

Chronic inflammation of the lamina propria

♦

May have active inflammation

♦

Tangential sectioning and chronic injury in the rectum can mimic CC, but the true basement membrane is thickened and often appears ribbonlike w ith a smooth interface

Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis

Clinical

♦

Wide range of clinical presentation including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, etc. (the usual suspects)

♦

May involve any part of the GI tract but most commonly involves the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine

♦

Must exclude parasitic infection, specific food sensitivity, etc; it is important to report increased eosinophils, to initiate further evaluation if indicated

♦

Most patients have allergic histories, allergic rhinitis, hay fever, asthma, etc

♦

Over 70% of patients have peripheral eosinophilia

Macroscopic

♦

Variable from mild patchy erythema to diffuse bowel wall thickening, with edema, and adhesions

Microscopic

♦

Prominent eosinophilic infiltrate

♦

Eosinophilic infiltrate of the submucosa with edema

♦

Eosinophils infiltrating the crypt and surface epithelium

♦

Eosinophilic infiltrate of the muscularis propria

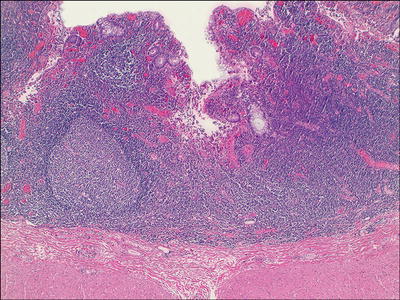

Diversion Colitis (Fig. 42.19 )

Fig. 42.19.

Diversion colitis.

Clinical

♦

Can occur in 90–100% of patients with a colostomy or ileostomy for various reasons, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

♦

Related to the depletion of fecal short-chain fatty acids and/or luminal bacterial stasis

♦

Persistent symptoms of mucus rectal discharge and abdominal pain

♦

Treatment includes reestablishment of fecal flow or short-chain fatty acid enemas

Macroscopic

♦

Mucosal erythema, friability, edema, and granularity, mimicking ulcerative colitis

♦

More severe in rectum than in the proximal colon

Microscopic

♦

Often moderate to marked mucosal chronic inflammation with prominent lymphoid hyperplasia

♦

Mucosa overlying lymphoid follicles may appear atrophic or eroded

♦

Mild architectural distortion away from lymphoid follicles

♦

Cryptitis, crypt abscesses, and e rosion may be seen.

Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome

Clinical

♦

Affects all age groups, but more common in the young

♦

Constipation, excessive straining, rectal pain, and mucus discharge

Macroscopic

♦

Affects anterior and anterolateral rectal wall

♦

Indurated, polypoid lesion, solitary or multiple

♦

Surface ul ceration

Microscopic

♦

Thickened muscularis mucosae with intramucosal smooth muscle proliferation between the crypts (features similar to mucosal prolapse elsewhere in the GI tract, but more exaggerated)

♦

Variable acute and chronic inflammation of the lamina propria

♦

Surface erosion and inflammatory exudate

♦

Submucosal entrapment of crypts filled with mucin (colitis cystic profunda) may occur

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Crohn disease

See above

−

Clinical history

Abnormal proximal colonic biopsies

♦

Malignancy-induced SRUS/mucosal prolapse

SRUS-like changes in the mucosa overlying a malignant infiltrate located in the submucosa or muscularis propria due to primary tumor or metastasis

Tumor cells may be seen in the biopsy

Immunohistochemistry may be required to identify these rare tumor cells

Perirectal mass or rectal wall thickening on computed tomography

♦

Radiation proctitis/co litis

See below

Radiation Proctitis/Colitis

Clinical

♦

History of radiation to pelvic or intra-abdominal malignancies

♦

Most common in rectosigmoid

♦

Symptoms appear during or shortly after therapy and may even appear months or years later

♦

Acute phase

Diarrhea, tenesmus, mucoid rectal discharge, and rectal bleeding

♦

Chronic phase/complications

10% of the cases

Tenesmus and mucoid rectal discharge, which may be bloody

Persistent decrease in stool caliber and constipation

Macroscopic

♦

Focal, l imited to the immediate field of irradiation

♦

Variably dusky and edematous mucosa with a blurred vascular pattern

♦

Friability and ulceration with a high dose of radiation

♦

Multiple mucosal telangiectasias and luminal narrowing with fibrosis

Microscopic

♦

Acute changes

Last for 1–2 months

Edematous lamina propria with fibrinoid vascular necrosis

Reactive endothelial and epithelial cells

Excess of apoptosis in the basal crypts

Mucosal neutrophilic infiltration

♦

Late changes

Mucosal atrophy with reduction of crypt epithelium

Crypt distortion, Paneth cell metaplasia, fibrosis, and smooth muscle proliferation

Dilated, telangiectatic blood vessels approaching the luminal surface

Diverticular Disease

Clinical

♦

Uncommon before age 40; approaching 50% by the ninth decade of life

♦

Most common in sigmoid in the USA; right-sided lesion more common in Asia

♦

Multifactorial pathogenesis including increased intraluminal pressure, colonic wall aging and motor dysfunction, and lack of dietary fiber

♦

Majority are asymptomatic.

♦

Presents with bloating, excessive flatulence, and intermittent abdominal pain

♦

Fever is associated with inflamed diverticula (diverticulitis).

Macroscopic

♦

Two rows on either side of the colon between mesenteric and antimesenteric teniae

♦

<1 cm, lie within the pericolic fat and especially the appendices epiploicae

♦

Markedly thickened colon wall

♦

Prominent mucosal ridges and intervening saccular dilatations

♦

Pericolic abscess formation is common

Microscopic

♦

Diverticula are lined by mucosa and submucosa and covered by pericolic connective tissue and serosa

♦

Hypertrophied muscularis propria at the neck of diverticulum

♦

In diverticulitis

Neutrophilic infiltration of the crypts, lamina propria, and surrounding pericolic fat

Prominent chronic inflammation and fibrosis

Foreign body giant c ells

Acute Appendicitis

Clinical

♦

Definitive causes unknown, but most likely secondary to luminal obstruction by fecalith, or, less commonly, a gallstone, a tumor, or worms, which results in ischemic injury

♦

Usually presents with acute onset of right lower-quadrant pain with chills and fever

Macroscopic

♦

Enlarged and congested appendix with often purulent serosal surface

♦

Reddened mucosa on cut surface

♦

Often with luminal pus

♦

Gangrenous necrosis of the muscular wall in advanced cases

♦

With or without perforation

Microscopic

♦

Neutrophilic infiltrate of the mucosa and the muscularis propria; the latter is generally required in the diagnosis

♦

Luminal inflammatory exudate

♦

Acute inflammation may be focal

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Y. enterocolitica infection

Prominent lymphoid aggregate with central zone necrotizing granuloma

♦

Parasitic infection

Luminal parasites of Enterobius vermicularis, amebae, and schistosomes

♦

Crohn disease

Lymphoplasmacytic transmural inflammation with lymphoid aggregates

Mural thickening

Occasional granulomas

♦

Ischemia

May be involved in ischemic injury of the right colon

Vascular Lesions

Acute Intestinal Ischemia (Table 42.1 )

Table 42.1.

Acute Ischemic Injury of the GI Tract

Stage of injury | Gross | Histology | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|

Mucosal necrosis | Mucosal congestion and erythema Shallow ulcers | Disintegration of surface and crypt epithelium Interstitial hemorrhage, edema, and neutrophilic infiltrate Mucosal outline usually preserved | Usually reversible |

Mural necrosis | Marked mucosal congestion, hemorrhage, and ulcers Serosal congestion | Mucosal and submucosal necrosis and hemorrhage Eosinophilic necrosis of inner smooth muscle layer | Progress to transmural necrosis Perforation |

Transmural necrosis | Gangrenous, flaccid, dilated, and serosal fibrinous exudate

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|