Small and Large Bowel Obstruction

L. D. Britt

Jay Collins

Jack R. Pickleman

Overview

There is a full spectrum of etiologies for both small and large bowel obstructions, with management being etiology dependent. However, there is an overarching concept that a large percentage of patients with small bowel obstruction can be definitively managed conservatively while the majority of patients presenting with obstruction of the large bowel will necessitate operative intervention and surgical extirpation. Although such a concept could be considered an oversimplification void to notable exceptions, it does appropriately frame the discussion regarding the management of small and large intestinal obstruction—with the first principle being differentiating between a small and large bowel obstruction (Table 1).

Epidemiology

Small Intestine

The most common surgical disorder of the small intestine is a mechanical small bowel obstruction. Until approximately the second half of the 20th century, the most common cause of a small bowel obstruction was external (or abdominal wall) hernias. With the steadily increasing number of intra-abdominal operations, along with elective herniorrhaphies, adhesions secondary to surgical dissection or inflammatory processes have become the number one etiology for small bowel obstruction (Table 2).

Table 1 Basic Differentiation Between Small and Large Bowel Obstruction | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

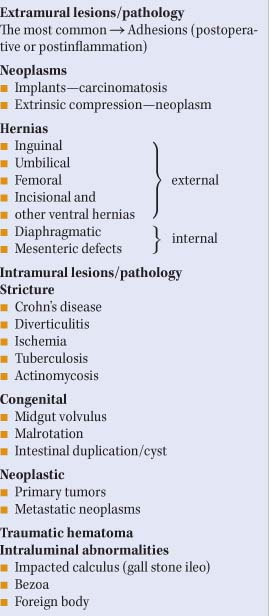

Table 2 Etiologies for Small Bowel Obstruction | |

|---|---|

|

Adhesive small bowel obstruction accounts for over two-thirds of the documented cases. It is estimated that over 300,000 operations are performed annually to definitively address adhesive small bowel obstruction. Any transabdominal or pelvic surgical procedure can predispose a patient to the development of postoperative adhesions. It should be noted that there has not been an appreciable decline in adhesive small bowel obstructions in this era of minimally invasive surgery. Intestinal incarceration, secondary to abdominal wall hernias, is now a less common cause of small bowel obstruction. Both adhesive small bowel obstruction and obstructing/incarcerated hernias are extrinsic etiologies. Small bowel obstruction can also be caused by intramural processes (e.g., neoplasms; inflammatory bowel-related strictures). Also, intraluminal blockage can occur as a result of a biliary calculus, meconium, intussusception, or foreign bodies. Small bowel obstruction secondary to a malignancy can be either extrinsic (e.g., carcinomatosis with implants) or intrinsic (e.g., primary small bowel tumor adenocarcinoma, carcinoid, lymphoma).

Relatively rare etiologies for mechanical small bowel obstruction includes, midgut volvulus and intestinal malrotation, along with mesenteric artery syndrome that results from the superior mesenteric artery extrinsically compressing the duodenum.

Relatively rare etiologies for mechanical small bowel obstruction includes, midgut volvulus and intestinal malrotation, along with mesenteric artery syndrome that results from the superior mesenteric artery extrinsically compressing the duodenum.

Pathophysiology and Related Symptomatology

Ingested liquids and secretion from the gastrointestinal tract account for the progressively increased fluid accumulation that occurs within the intestinal tract proximal to the site of obstruction. The resulting colicky pain is associated with the compensatory increased intestinal motility that initially occurs to counter the obstruction. However, such intestinal activity eventually subsides, and there are fewer contractions. This corresponds to hyperactive bowel sounds during the early phase of small bowel obstruction and decrease activity in the late stage. Optimal intestinal microvascular perfusion is compromised with increasing intestinal intraluminal pressure, which is a prelude to the development of strangulated bowel obstruction. The typical symptomatology for patients with small bowel obstruction includes malaise, nausea, emesis, bloating, and colicky abdominal pain. The extent of abdominal distension can correlate with the site of obstruction, with a distal ileal obstruction resulting in marked abdominal distention and a more proximal intestinal blockage having minimal, if any, abdominal distension. The development of obstipation (the inability of patients to pass either flatus or stool) should be considered an ominous sign.

In addition to ensuring an adequate airway and optimal ventilation, assessing and appropriately addressing the associated volume contraction are essential management steps during the initial assessment of a patient with a suspected small bowel obstruction. It is not uncommon for patients to present lethargy, tachycardia, and with some degree of abdominal distension. In the early stage of small bowel obstruction, the presentation could be less impressive. However, if the patient presents with fever, tachycardia, abdominal tenderness, and an associated leukocytosis, early operative intervention should be considered because of the likelihood of ischemic or strangulated bowel. Delaying further surgical management and allowing the patient’s condition to worsen, with the development of refractory acidosis or flank peritonitis, is unacceptable and falls below the standard of care in any hospital setting. Because the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction is invariably made during clinical evaluation, a careful history and thorough physical examination are imperative. In addition to previous episodes of intestinal obstruction, antecedent disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., Crohn’s disease), could predispose a patient to developing a small bowel obstruction. Physical findings, such as an incarcerated abdominal hernia or four-quadrant rebound tenderness, often dictate the management required before any diagnostic study is considered. Rectal examination should always be performed to determine if there is any occult bleeding or an obstructing rectal mass.

As mentioned above, the diagnosis of a small bowel obstruction is often based on clinical findings, with plain radiographic confirmation. However, the computed tomography (CT) scan is being utilized more frequently in those patients who have no indication for emergency exploration. Both the specificity and sensitivity of CT scan have been documented to be as high as 90% in prospective trials. The delineation of pathology is an advantage for CT evaluations as an obstructing lesion or a transition point can be demonstrated.

Other diagnostic options include performing small bowel series, utilizing contrast agents. The standard small bowel series, often called the small bowel follow-through, is performed by having a contrast agent instilled by swallowing or via a nasogastric tube. The contrast preference for many is Gastrografin, a water-soluble agent that causes less of an inflammatory reaction if it interfaces with tissue planes as a result of a bowel perforation. While barium allows for better delimitation of the intraluminal contents, leakage can initiate inflammatory reaction on contact with the surrounding tissue. For a more optimal assessment of the mucosa anatomy and intraluminal content, enteroclysis (double-contrast instillation directly into the proximal jejunum) has been advocated. However, enteroclysis is not indicted in the acute setting.

Definitive Management

After adequate volume resuscitation and correction of electrolyte derangements, surgical management, if indicated, should commence with exploratory laparotomy, with an emphasis on definitively addressing the obstructing site. The basic operative strategy would likely entail adhesiolysis and resection of nonviable intestine and/or extirpation of the obstructing lesion. If viability of a segment of bowel is questionable, it can be wrapped in a warm, saline-soaked towel and reinspected several minutes later. Also, a Woods lamp assessment can be made after administration of fluorescein. Laser Doppler flowmetry has been advocated as an intraoperative assessment tool in order to determine bowel viability. If the lesion is felt to be a neoplasm, the tumor

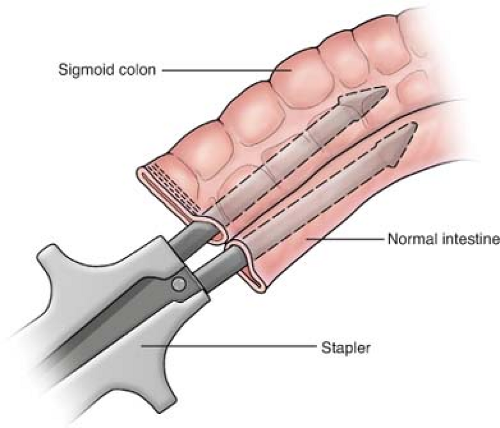

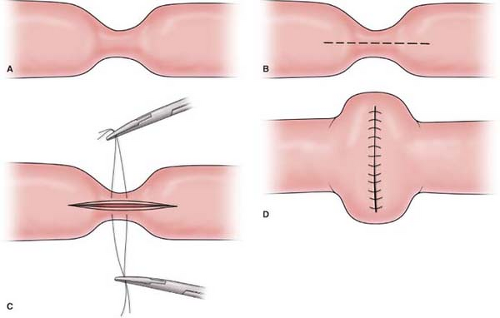

should be resected with a wide margin of 8 to 10 cm (proximal and distal to the lesion) of normal bowel and a wedge resection of the lymph node basin for the involved segment being resected. The resection should be followed by a primary anastomosis (end to end or functional end to end), with closure of the mesenteric defect. The anastomosis is performed by stapling (Fig. 1), using a GIA stapler. The resulting enterotomy site is primarily closed using a running 3-0 Vicryl for the mucosal closure and followed by placement of 3-0 silk suture in the seromuscular layer in a Lembert manner. Performing a stricturoplasty (Fig. 2) of an obstructing intestinal segment is a viable option for a special cohort of patients (e.g., Crohn’s disease patients) who have had prior small bowel resections, and preservation of intestinal length is necessary in order to avoid a possible short bowel syndrome.

should be resected with a wide margin of 8 to 10 cm (proximal and distal to the lesion) of normal bowel and a wedge resection of the lymph node basin for the involved segment being resected. The resection should be followed by a primary anastomosis (end to end or functional end to end), with closure of the mesenteric defect. The anastomosis is performed by stapling (Fig. 1), using a GIA stapler. The resulting enterotomy site is primarily closed using a running 3-0 Vicryl for the mucosal closure and followed by placement of 3-0 silk suture in the seromuscular layer in a Lembert manner. Performing a stricturoplasty (Fig. 2) of an obstructing intestinal segment is a viable option for a special cohort of patients (e.g., Crohn’s disease patients) who have had prior small bowel resections, and preservation of intestinal length is necessary in order to avoid a possible short bowel syndrome.

Special Circumstances

Advanced Malignancy Small Bowel Obstruction and Intestinal

Intestinal obstruction in patients with documented advanced primary or metastatic intra-abdominal malignancies can occur in up to 40% of this cohort of patients. Ovarian and colorectal malignant neoplasms are the most common primary tumors in this setting; however, small bowel obstruction can also occur in patients with extra-abdominal primary tumors, such as melanoma, breast, and lung. With long-term survival in these patients being so limited, a more palliative, nonoperative approach to the intestinal obstruction should be entertained. In light of the overall poor progress of patients with these advanced malignances, realistic treatment options (with the associated risks) must be objectively discussed with the individual patient and family in order to align expectations with the patient’s and family’s desires/needs.

With morbidity and recurrent obstruction as high as 42% and 50%, respectively, being reported, nonoperative options need to be part of the management armamentarium. Volume resuscitation, along with nasogastric decompression, should always be considered for the initial management. More time should be allowed to see if this simple and relatively noninvasive intervention will result in some degree of resolution of the obstruction. In addition, endoscopic stent placement should be considered as a possible management option. Such an intervention has been reported to have successfully relieved obstruction at different sites along the intestinal tract.

Laparoscopic Approach to Small Bowel Obstruction

The decision to undergo a laparoscopic or open approach is surgeon dependent; however, the laparoscopic approach is gaining popularity. Although the laparoscopic approach to bowel obstruction is a procedure requiring advanced laparoscopic skills, it has been shown to be both technically feasible and safe. Such an approach may not be appropriate or successful for all patients. However, the advantages of laparoscopic procedures over open operations are well described. These patients have fewer wound problems, such as infections, dehiscence, and herniation. Other advantages may include less pain, less narcotic usage, less postoperative pneumonia, quicker resolution of postoperative ileus, better cosmesis, decreased length of stay, and quicker return to normal everyday activities. Not all patients will be appropriate candidates for a laparoscopic approach (Table 3). Patient who are hypotensive, in septic shock, or likely to have ischemic or gangrenous bowel requiring a major resection may best be served by an open approach. This may provide easier resection of bowel, a quicker operation, and return to the intensive care unit (ICU) for ongoing resuscitation. Pneumoperitoneum is not advisable in

hypovolemic patients as this may worsen end organ perfusion. The two main reasons the laparoscopic approach is not successful is lack of an adequate working space and very dense, matted adhesions. One must be able to create pneumoperitoneum and an adequate environment in which to maneuver. This is much more difficult in patients who have had multiple laparotomies or in patients who have had severe intra-abdominal sepsis and abscesses with extensive dense adhesions to the anterior abdominal wall. However, the adhesiolysis, necessary in this patient population, would also be difficult during an open procedure. In patients with a very distal obstruction, chronic obstruction, or many significantly dilated loops of bowel, the establishment of pneumoperitoneum may not be safe or possible. Therefore, without an adequate working environment, a laparoscopic operation cannot be performed.

hypovolemic patients as this may worsen end organ perfusion. The two main reasons the laparoscopic approach is not successful is lack of an adequate working space and very dense, matted adhesions. One must be able to create pneumoperitoneum and an adequate environment in which to maneuver. This is much more difficult in patients who have had multiple laparotomies or in patients who have had severe intra-abdominal sepsis and abscesses with extensive dense adhesions to the anterior abdominal wall. However, the adhesiolysis, necessary in this patient population, would also be difficult during an open procedure. In patients with a very distal obstruction, chronic obstruction, or many significantly dilated loops of bowel, the establishment of pneumoperitoneum may not be safe or possible. Therefore, without an adequate working environment, a laparoscopic operation cannot be performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree