Skin Disorders

INTRODUCTION

Skin is the body’s front-line protective barrier between internal structures and the external environment. It’s tough, resilient, and virtually impermeable to aqueous solutions, bacteria, or toxic compounds. It also performs many vital functions. Skin protects against trauma, regulates body temperature, serves as an organ of excretion and sensation, and synthesizes vitamin D in the presence of ultraviolet light. Skin varies in thickness and other qualities from one part of the body to another, which often accounts for the distribution of skin diseases.

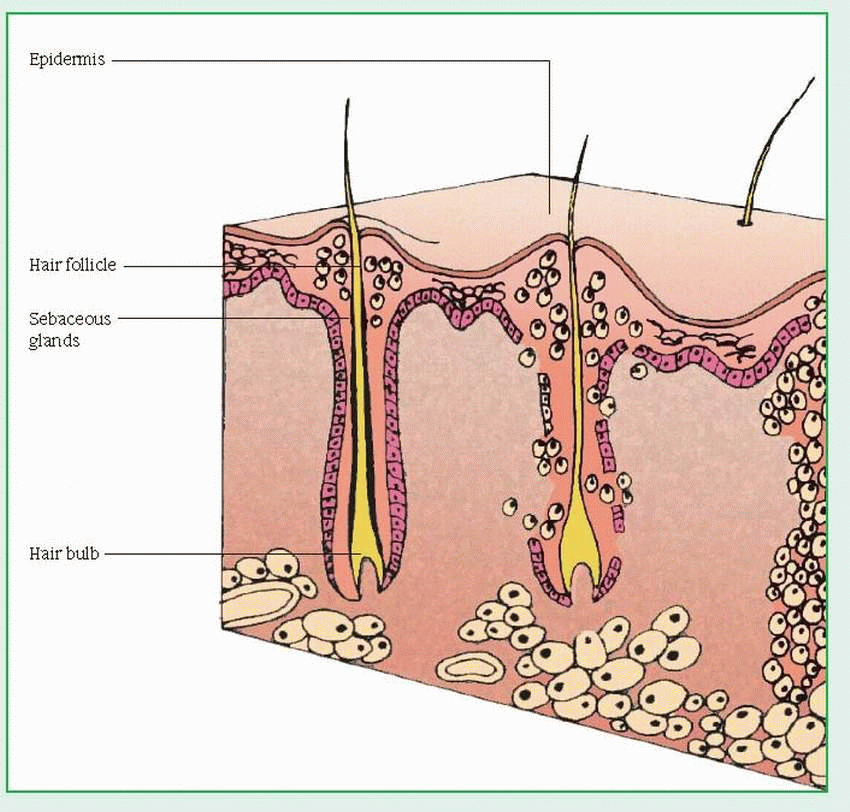

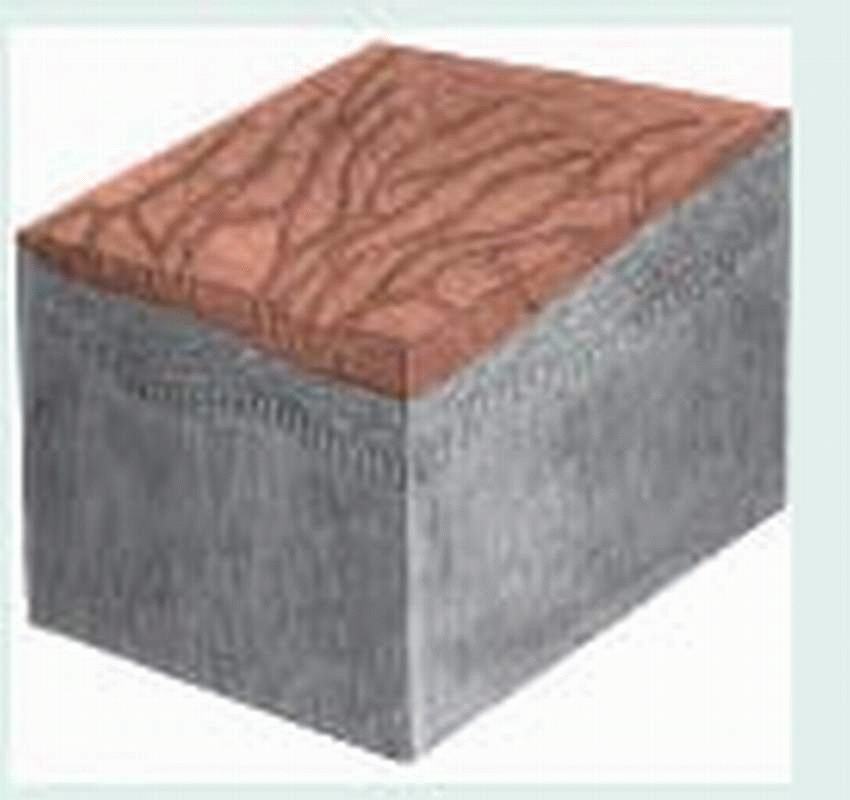

Skin has three primary layers: epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. The epidermis (the outermost layer) produces keratin as its primary function. This layer is generally thin but is thicker in areas subject to constant pressure or friction, such as the soles and palms. The epidermis contains two sublayers: the stratum corneum, an outer horny layer of keratin that protects the body against harmful environmental substances and restricts water loss, and the cellular stratum, where keratin cells are synthesized. The basement membrane lies beneath the cellular stratum and serves to attach the epidermis to the dermis.

The cellular stratum, the deepest layer of the epidermis, consists of the basal layer, where mitosis takes place; the stratum spinosum, where cells begin to flatten, and fibrils—precursors of keratin—start to appear; and the stratum granulosum, made up of cells containing deeply staining granules of keratohyalin, which are generally thought to become the keratin that forms the stratum corneum. A skin cell moves from the basal layer of the cellular stratum to the stratum corneum in about 14 days. After another 14 days, normal wear and tear on the skin causes it to slough off. The epidermis also contains melanocytes, which produce the melanin that gives the skin its color, and Langerhans cells, which are involved in a variety of immunologic reactions.

The dermis, the second primary layer of the skin, consists of two fibrous proteins, fibroblasts, and an intervening ground substance. The proteins are collagen, which strengthens the skin to prevent it from tearing, and elastin to give it resilience. The ground substance, which makes the skin soft and compressible, contains primarily jellylike mucopolysaccharides. Two distinct layers constitute the dermis: the papillary dermis (top layer) and the reticular dermis (bottom layer).

Subcutaneous tissue, the third primary layer of the skin, consists mainly of fat (containing mostly triglycerides), which provides heat, insulation, shock absorption, and a reserve of calories. Both sensory and motor nerves (autonomic fibers) are found in the dermis and the subcutaneous tissue.

NAILS, GLANDS, AND HAIR

Nails are epidermal cells converted to hard keratin. The bed on which the nail rests is highly vascular, making the nail appear pink; the whitish, crescent-shaped area extending beyond the proximal nail fold, called the lunula—most visible in the thumbnail—marks the end of the matrix, the site of mitosis and of nail growth.

Sebaceous glands, found everywhere on the body (but mostly on the face and scalp) except the palms and soles, serve as appendages of the dermis. These glands generally excrete sebum into hair follicles, but in some cases, they empty directly onto the skin surface. Sebum is an oily substance that helps keep the skin and hair from drying out and prevents water and heat loss. Sebaceous glands abound on the scalp, forehead, cheeks, chin, back, and genitalia, and may be stimulated by sex hormones—primarily testosterone.

The dermis and subcutaneous tissue contain eccrine and apocrine glands, and hair. Eccrine sweat glands open directly onto the skin and regulate body temperature. Innervated by sympathetic nerves, these sweat glands are distributed throughout the body, except for the lips, ears, and parts of the genitalia. They secrete a hypertonic solution made up mostly of water and sodium chloride; the prime stimulus for eccrine gland secretion is heat. Other stimuli include muscular exertion and emotional stress.

Apocrine sweat glands appear chiefly in the axillae and genitalia; they’re responsible for producing body odor and are stimulated by emotional stress. The sweat produced is sterile but undergoes bacterial decomposition on the skin surface. These glands become functional after puberty. (Ceruminous glands, located in the external ear canal, appear to be modified sweat glands and secrete a waxy substance known as cerumen.)

Hair grows on most of the body, except for the palms, the soles, and parts of the genitalia. An individual hair consists of a shaft (a column of keratinized cells), a root (embedded in the dermis), the hair follicle (the root and its covering), and the hair papilla (a loop of capillaries at the base of the follicle). Mitosis at the base of the follicle causes the hair to grow; the papilla provides nourishment for mitosis. Small bundles of involuntary muscles known as arrectores pilorum cling to hair follicles. When these muscles contract, usually during moments of cold, fear, or shock, the hairs stand on end, and the person is said to have goose bumps or gooseflesh. Melanocytes in the

matrix (inner core) of the hair bulb produce melanin, which passes into the innermost layers of the hair and is responsible for hair color. Dark hair contains mostly true melanin. Blond and red hair contains variants of melanin that have iron and more sulfur. Gray hair results from pigment loss due to a decline of tyrosinase, which is required for melanin synthesis. White hair occurs when air bubbles accumulate in the center of the hair shaft.

matrix (inner core) of the hair bulb produce melanin, which passes into the innermost layers of the hair and is responsible for hair color. Dark hair contains mostly true melanin. Blond and red hair contains variants of melanin that have iron and more sulfur. Gray hair results from pigment loss due to a decline of tyrosinase, which is required for melanin synthesis. White hair occurs when air bubbles accumulate in the center of the hair shaft.

VASCULAR INFLUENCE

The skin is served by a vast arteriovenous network, extending from subcutaneous tissue to the dermis. These blood vessels provide oxygen and nutrients to sensory nerves (which control touch, temperature, and pain), motor nerves (which control the activities of sweat glands, the arterioles, and smooth muscles of the skin), and skin appendages. Blood flow also influences skin coloring because the amount of oxygen carried to capillaries in the dermis can produce transient changes in color. For example, decreased oxygen supply can turn the skin pale or bluish; increased oxygen can turn it pink or ruddy.

ASSESSING SKIN DISORDERS

Assessment begins with a thorough patient history to determine whether a skin disorder is an acute flare-up, a recurrent problem, or a chronic condition. Ask the patient how long he has had the disorder; how a typical flare-up or attack begins; whether or not it itches; and what medications—systemic or topical—have been used to treat it. Also, find out if any of his family members, friends, or contacts have the same disorder, and if he lives or works in an environment that could cause the condition. Also ask about hobbies.

When examining a patient with a skin disorder, be sure to look everywhere—mucous membranes, hair, scalp, axillae, groin, palms, soles, and nails. Note moisture, temperature, texture, thickness, mobility, edema, turgor, and any irregularities in skin color. Look for skin lesions; if you find a lesion, record its color, shape, size, and location. (See Differentiating among skin lesions.) Try to determine which is the primary lesion—the one that appeared first—which always starts in normal skin. The patient might be able to point it out.

If more than one lesion is in evidence, note the pattern of distribution. Lesions can be localized (isolated), regional, general, or universal (total), involving the entire skin, hair, and nails. Also, observe whether the lesions are unilateral or bilateral and symmetrical or asymmetrical; also note the arrangement of the lesions (clustered or linear configuration, for example).

DIAGNOSTIC AIDS

After simple observation, and examination of the affected area of the skin with a dermatoscope for morphologic detail, the following clinical diagnostic techniques may help to identify skin disorders:

Biopsy determines histology of cells and may be diagnostic, confirmatory, or inconclusive, depending on the disease.

Diascopy, in which a lesion is covered with a microscopic slide or piece of clear plastic, helps determine whether dilated capillaries or extravasated blood is causing the redness of a lesion.

Gram stains and exudate cultures help identify the organism responsible for an underlying infection.

Microscopic immunofluorescence identifies immunoglobulins and elastic tissue in detecting skin manifestations of immunologically mediated disease.

Patch tests identify contact sensitivity (usually with dermatitis).

Potassium hydroxide preparations permit examination for mycelia in fungal infections.

Side-lighting shows minor elevations or depressions in lesions; it also helps determine the configuration and degree of eruption.

Subdued lighting highlights the difference between normal skin and circumscribed lesions that are hypopigmented or hyperpigmented.

Wood’s light examination reveals yellow, green, or blue-green fluorescence when an area is infected with certain dermatophytes (fungi).

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

When assessing a skin disorder, keep in mind its distressing social and psychological implications. Unlike internal disorders, such as cardiac disease or diabetes mellitus, a skin condition is usually obvious and disfiguring. Understandably, the psychological implications are most acute when skin disorders affect the face— especially during adolescence, an emotionally turbulent time of life. However, such disorders can also create tremendous psychological problems for adults. A skin disease usually interferes with a person’s ability to work because the condition affects the hands or because it distresses the patient to such an extent that he can’t function.

For these reasons, be empathetic and accepting. Above all, don’t be afraid to touch such a patient; most skin disorders aren’t contagious. Touching the patient naturally and without hesitation helps show your acceptance of the dermatologic condition. Such acceptance is no

less important than your patient-teaching about the disease and your guidance and help with carrying out prescribed treatment.

less important than your patient-teaching about the disease and your guidance and help with carrying out prescribed treatment.

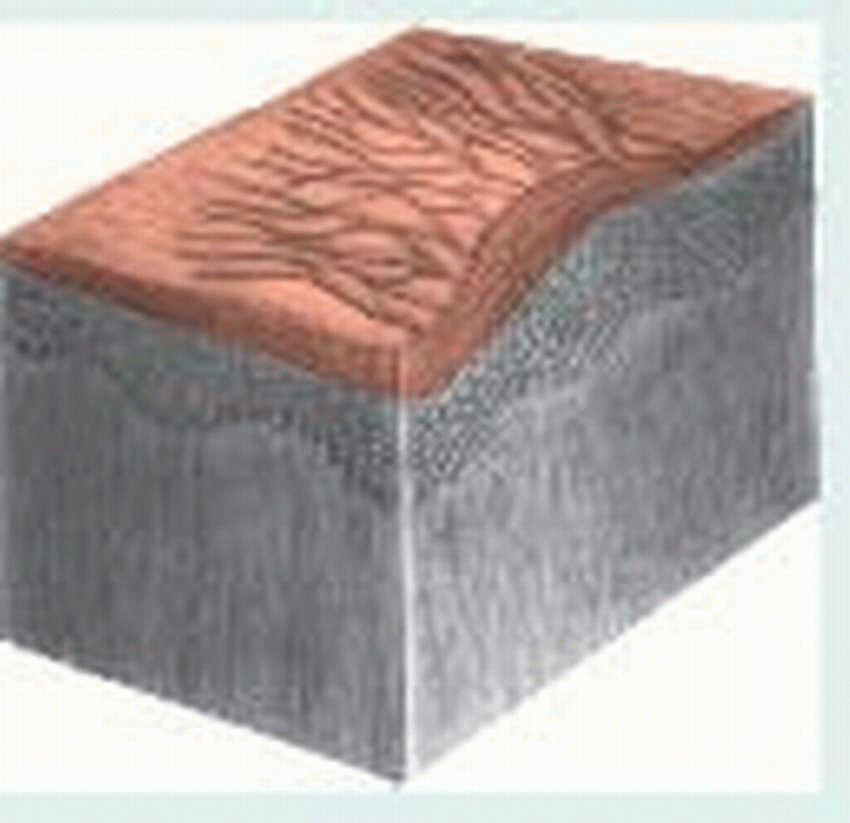

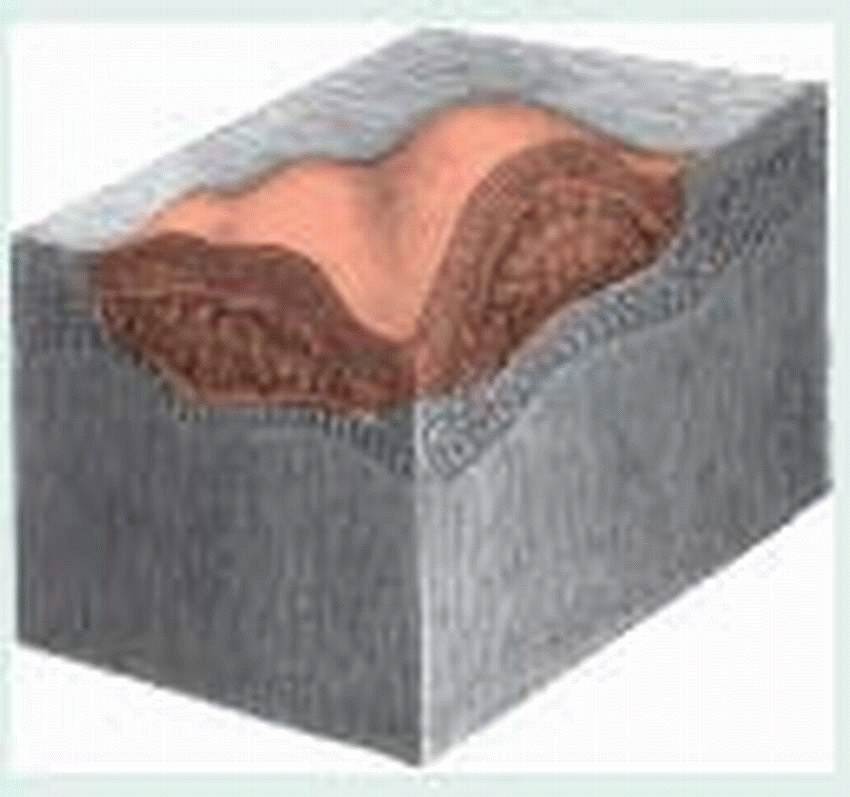

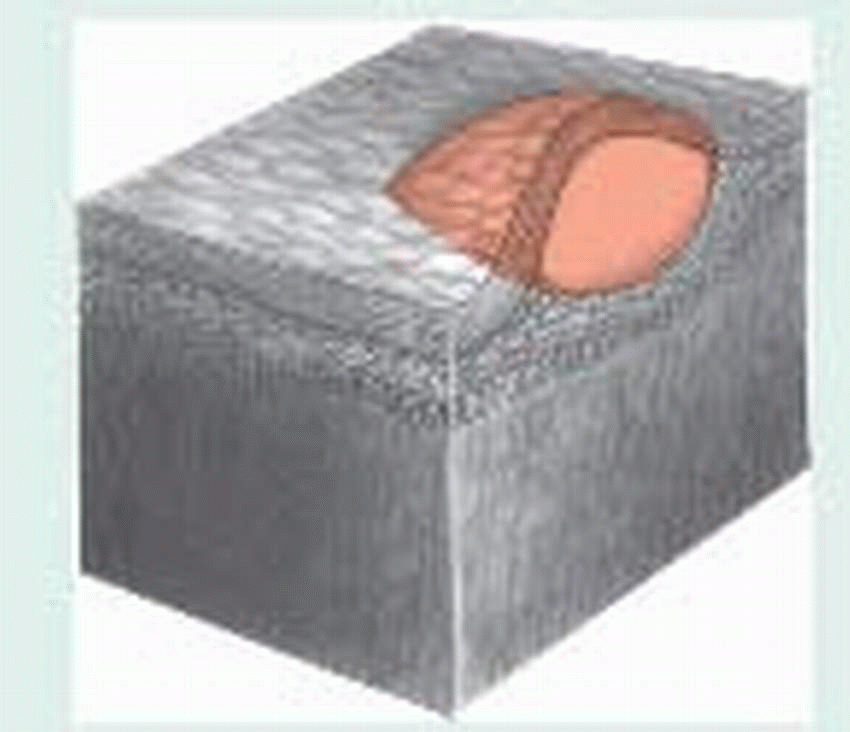

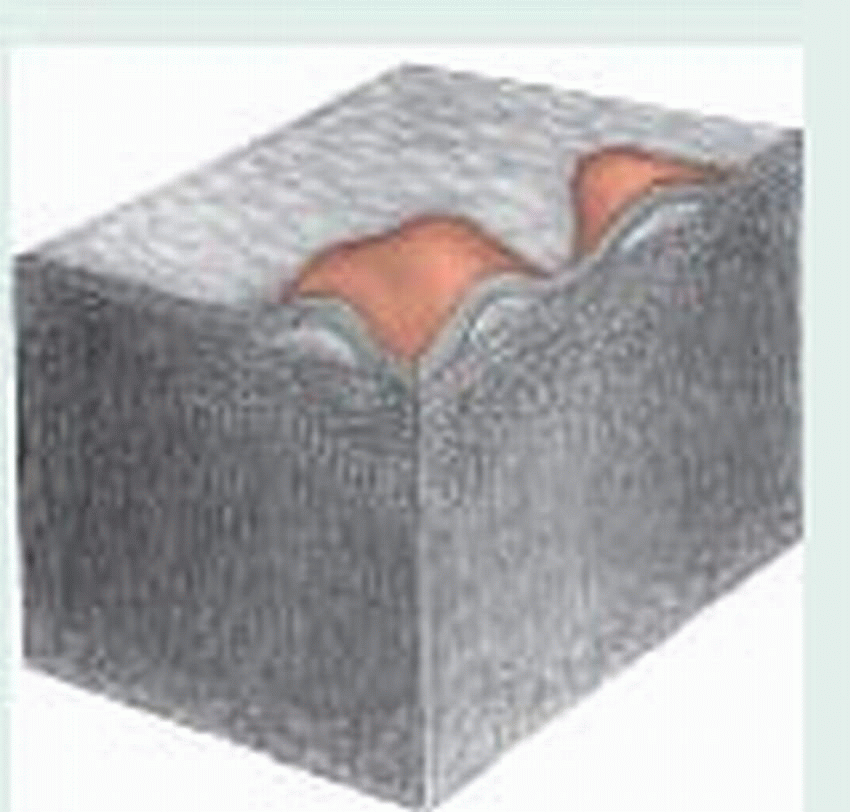

Differentiating among skin lesions

The illustrations below depict the most common primary and secondary skin lesions.

Primary Lesions

Bulla: Fluid-filled lesions more than 2 cm in diameter (also called blister), as occurs in severe poison oak or ivy dermatitis, bullous pemphigoid, and seconddegree burns

|

Comedo: Plugged, exfoliative pilosebaceous duct formed from sebum and keratin—for example, blackhead (open comedo) and whitehead (closed comedo)

|

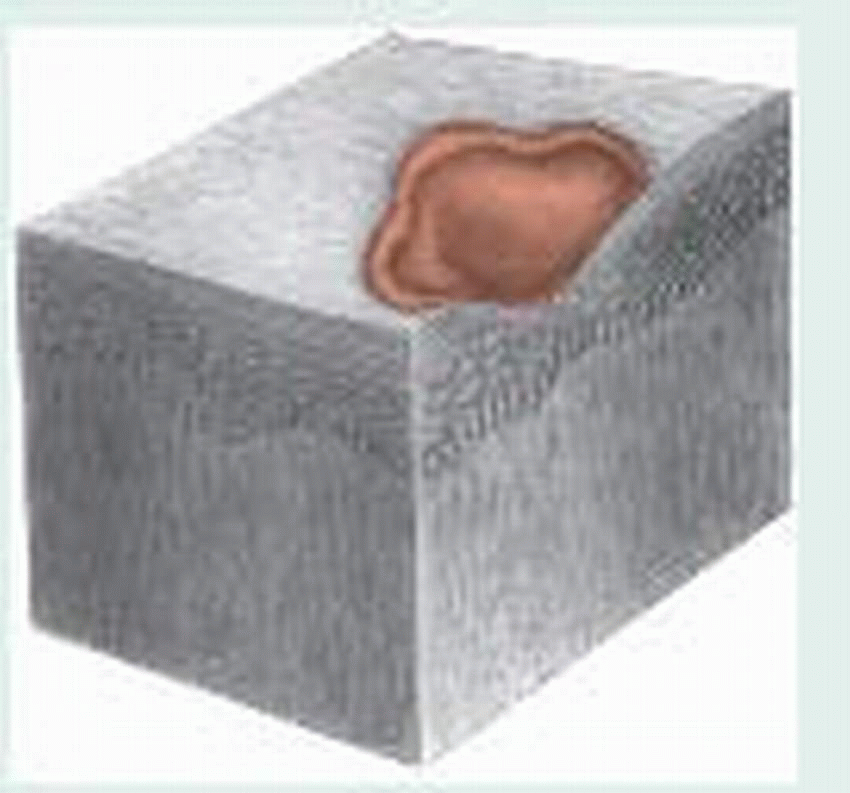

Cyst: Semisolid or fluidfilled encapsulated mass extending deep into dermis—for example, acne

|

Macule: Flat, pigmented, circumscribed area less than 1 cm in diameter—for example, freckle or rash that occurs in rubella

|

Nodule: Firm, raised lesion, 0.5 to 2 cm in diameter, that’s deeper than a papule and extends into dermal layer—for example, intradermal nevus

|

Papule: Firm, inflammatory raised lesion up to 0.5 cm in diameter that may be the same color as skin or pigmented—for example, acne papule and lichen planus

|

Patch: Flat, pigmented, circumscribed area more than 1 cm in diameter—for example, herald patch (pityriasis rosea)

|

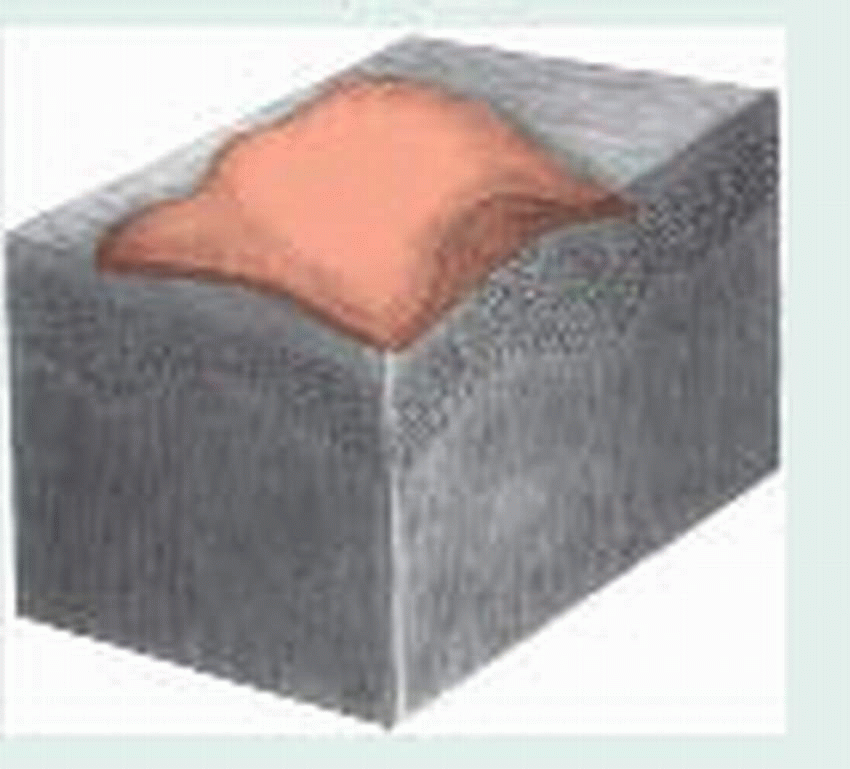

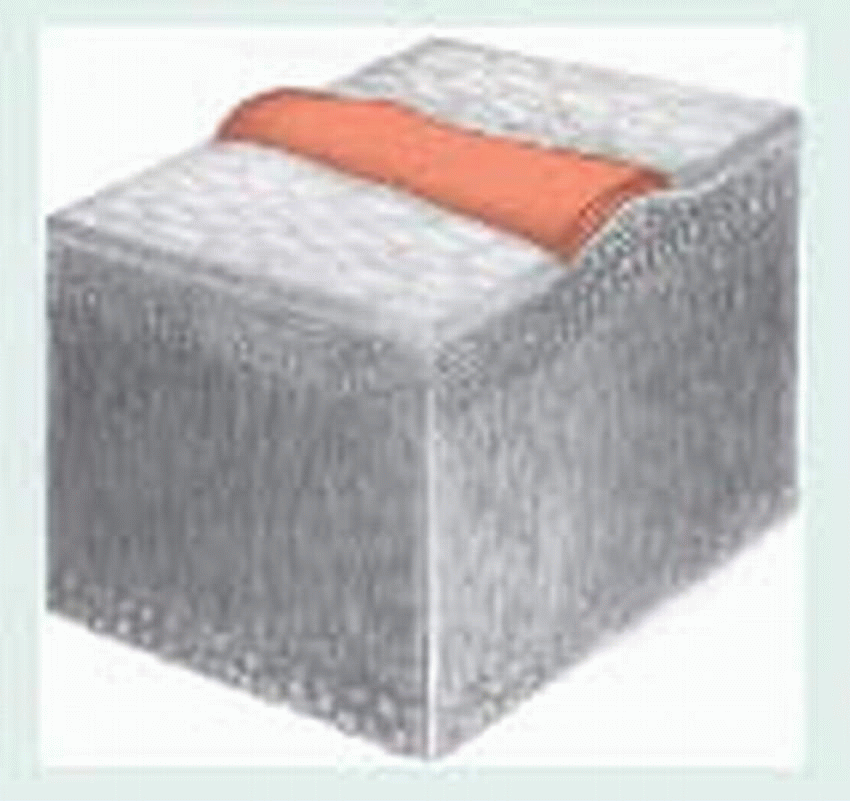

Plaque: Circumscribed, solid, elevated lesion more than 1 cm in diameter that is elevated above skin surface and occupies larger surface area in comparison with height, as occurs in psoriasis

|

Pustule: Raised, circumscribed lesion, usually less than 1 cm in diameter, containing purulent material, making it a yellow-white color—for ˆ example, acne or impetiginous pustule and furuncle

|

Tumor: Elevated, solid lesion larger than 2 cm in diameter that extends into dermal and subcutaneous layers—for example, dermatofibroma

|

Vesicle: Raised, circumscribed, fluid-filled lesion less than 0.5 cm in diameter, as occurs in chickenpox or herpes simplex infection

|

Wheal: Raised, firm lesion with intense localized skin edema that varies in size, shape, and color (from pale pink to red) and that disappears in hours—for example, hives and insect bites

|

Secondary Lesions

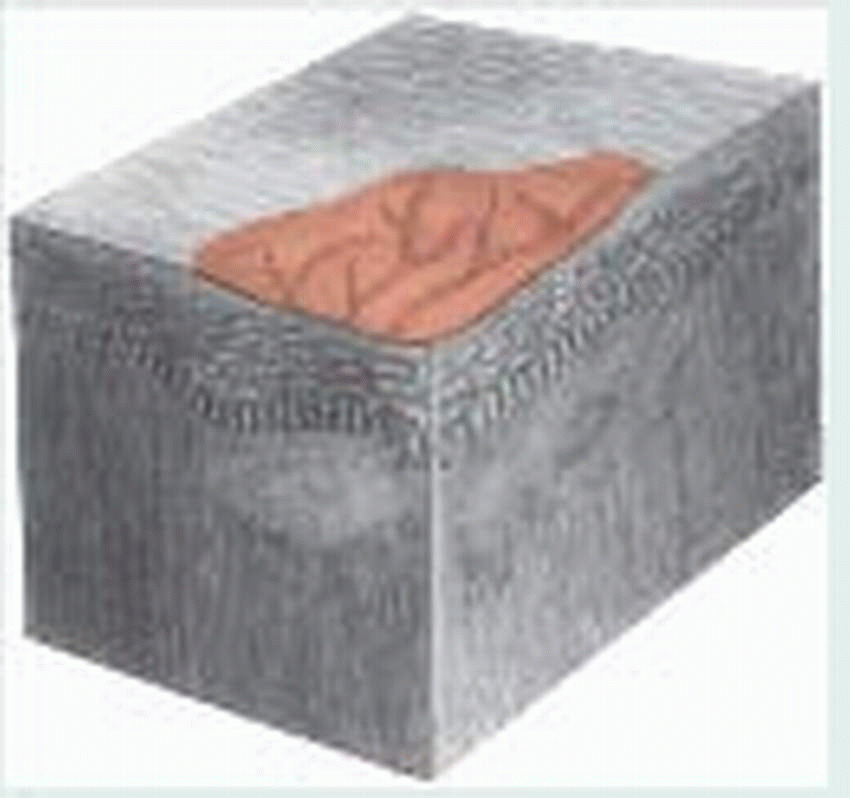

Atrophy: Thinning of skin surface at site of disorder—for example, striae and aging skin

|

Crust: Dried sebum or serous, sanguineous, or purulent exudate, overlying an erosion or a weeping vesicle, bulla, or pustule, as occurs in impetigo

|

Erosion: Circumscribed lesion that involves loss of superficial epidermis—for example, abrasion

|

Excoriation: Linear scratched or abraded areas, often self-induced—for example, abraded acne lesions or eczema

|

Fissure: Linear cracking of the skin that extends into the dermal layer—for example, hand dermatitis (chapped skin)

|

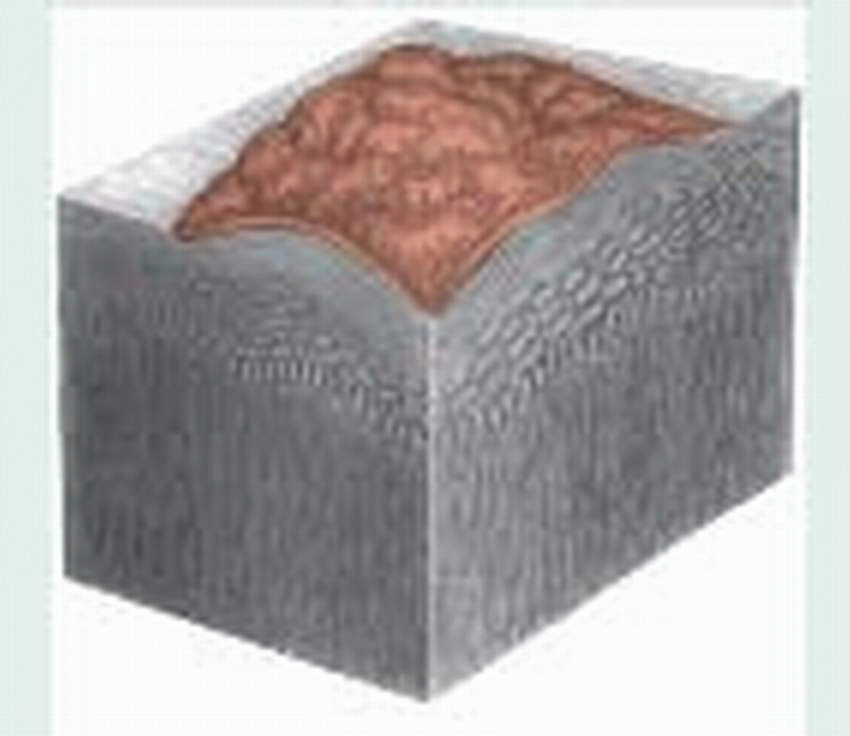

Lichenification: Thickened, prominent skin markings caused by constant rubbing, as occurs in chronic dermatitis

|

Scale: Thin, dry flakes of shedding skin, as occurs in psoriasis, dry skin, or neonatal desquamation

|

Scar: Fibrous tissue caused by trauma, deep inflammation, or surgical incision, which can be red and raised (recent) pink and flat (6 weeks), or pale and depressed (old)—for example, a healed surgical incision

|

Ulcer: Epidermal and dermal destruction that may extend into subcutaneous tissue and that usually heals with scarring—for example, pressure ulcer or stasis ulcer

|

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Impetigo

A contagious, superficial skin infection, impetigo occurs in nonbullous and bullous forms. This vesiculopustular eruptive disorder spreads most easily among infants, young children, and elderly people. Predisposing factors, such as poor hygiene, anemia, malnutrition, and a warm climate, favor outbreaks of this infection, most of which occur during the late summer and early fall. Impetigo can complicate chickenpox, eczema, or other skin conditions marked by open lesions.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus and, less commonly, group A beta-hemolytic streptococci usually produce nonbullous impetigo; S. aureus (especially phage type 71) generally causes bullous impetigo.

COMPLICATIONS

Ecthyma

Glomerulonephritis

Permanent scarring

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Common nonbullous impetigo typically begins with a small red macule that turns into a vesicle or pustule. When the vesicle breaks, a thick yellow crust forms from the exudate. (See Recognizing impetigo.) Autoinoculation may cause satellite lesions. Although it can occur anywhere, impetigo usually occurs around the mouth and nose and on the knees and elbows. Other features include pruritus, burning, and regional lymphadenopathy.

A rare but serious complication of streptococcal impetigo is glomerulonephritis, which is more likely to occur when many members of the same family have impetigo.

Infants and young children may develop aural impetigo or otitis externa; the lesions usually clear without treatment in 2 to 3 weeks, unless an underlying disorder such as eczema is present. Scarlet fever also may occur.

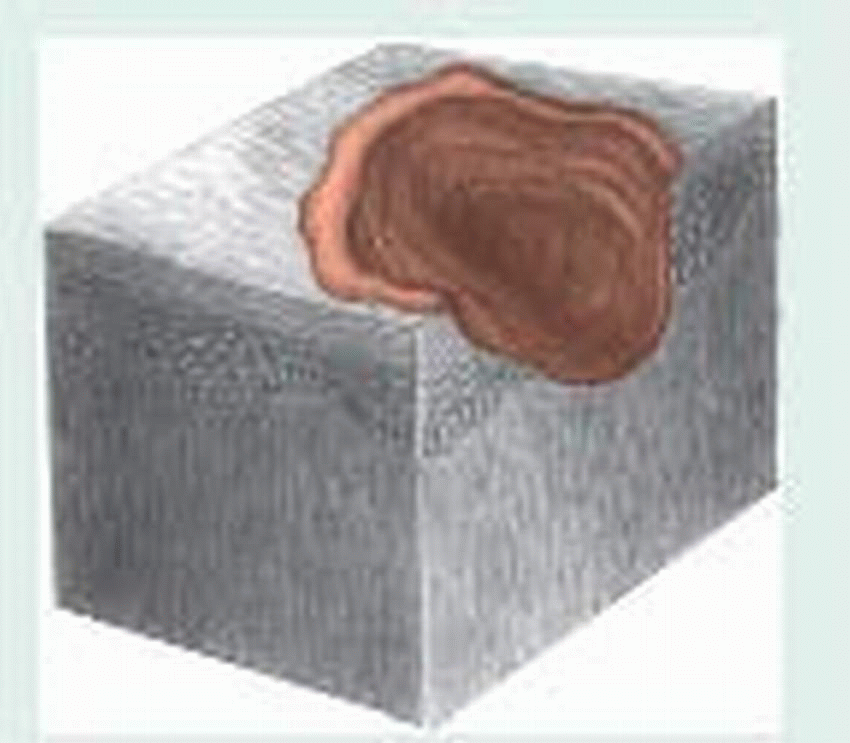

In bullous impetigo, a thin-walled vesicle opens, and a thin, clear crust forms from the exudate. The lesion consists of a central clearing, circumscribed by an outer ring—much like a ringworm lesion—and commonly appears on the face or other exposed areas. Both forms usually produce painless itching; they may appear simultaneously and be clinically indistinguishable.

DIAGNOSIS

Culture and sensitivity testing of fluid or denuded skin may indicate the most appropriate antibiotic, but therapy shouldn’t be delayed for laboratory results, which can take 3 days. White blood cell count may be elevated in the presence of infection.

TREATMENT

Topical mupirocin and retapamulin are the treatments of choice if the lesions aren’t too extensive. These drugs are highly effective against group A beta-hemolytic streptococci and S. aureus, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus. Mupirocin also eliminates nasal carriers of these organisms. Extensive or nonresolving lesions require systemic antibiotics.

Therapy may also include removal of the exudate by washing the lesions two or three times a day with soap and water (or antibacterial soap) or, for stubborn crusts, warm soaks or compresses of normal saline or a diluted soap solution.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Urge the patient not to scratch, because this spreads impetigo.

Advise parents to cut their child’s fingernails and cover his hands with socks or mittens to prevent scratching.

Give medications as indicated. Remember to check for medication allergy. Stress the need to continue prescribed medications for 7 to 10 days, even after lesions have healed.

Teach the patient or his family how to care for impetiginous lesions.

To prevent further spread of this highly contagious infection, encourage frequent bathing using a bactericidal soap. Tell the patient not to share towels, washcloths, or bed linens with family members. Emphasize the importance of following proper hand-washing technique.

Check family members for impetigo. If this infection is present in a school-age child, notify his school.

Ecthyma

Ecthyma is a superficial skin infection that usually causes scarring. It commonly occurs in persons with poor hygiene or in those living in crowded conditions and generally results from infection by Staphylococcus aureus or group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. Ecthyma differs from impetigo in that its characteristic ulcer results from deeper penetration of the skin by the infecting organism (involving the lower epidermis and dermis), and the overlying crust tends to be piled high (1 to 3 cm). These lesions are usually found on the legs after a scratch or bug bite. Autoinoculation can transmit ecthyma to other parts of the body, especially to sites that have been scratched open. Therapy is basically the same as for impetigo, but response may be slower. Parenteral antibiotics (usually a penicillinase-resistant penicillin) are also used.

Folliculitis, furunculosis, and carbunculosis.

Folliculitis is a bacterial infection of the hair follicle that causes the formation of a pustule. The infection can be superficial (follicular impetigo or Bockhart’s impetigo) or deep (sycosis barbae). Folliculitis may also lead to the development of furuncles (furunculosis), commonly known as boils, or carbuncles (carbunculosis), which involve multiple contiguous hair follicles. The prognosis depends on the severity of the infection and on the patient’s physical condition and ability to resist infection.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The most common cause of folliculitis, furunculosis, or carbunculosis is coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus. Predisposing factors include an infected wound, poor hygiene, debilitation, diabetes, alcoholism, occlusive cosmetics, tight clothes, friction, chafing, exposure to chemicals, and treatment for skin lesions with tar or with occlusive therapy, using steroids. Furunculosis often follows folliculitis exacerbated by irritation, pressure, friction, or perspiration. Carbunculosis follows persistent S. aureus infection and furunculosis.

COMPLICATIONS

Cellulitis

Septicemia

Scarring

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Pustules of folliculitis usually appear in a hair follicle on the scalp, arms, and legs in children; on the face of bearded men (sycosis barbae); and on the eyelids (styes). Deep folliculitis may be painful.

Folliculitis may progress to the hard, painful nodules of furunculosis, which commonly develop on the neck, face, axillae, and buttocks. For several days these nodules enlarge, and then rupture, discharging pus and necrotic material. After the nodules rupture, pain subsides, but erythema and edema may persist for days or weeks.

Carbunculosis is marked by extremely painful, deep abscesses that drain through multiple openings onto the skin surface, usually around several hair follicles. Fever and malaise may accompany these lesions. (See Follicular skin infections, page 669.)

DIAGNOSIS

The obvious skin lesion confirms folliculitis, furunculosis, or carbunculosis. Wound culture shows S. aureus; sensitivity will help guide antibiotic therapy.

In carbunculosis, patient history reveals preexistent furunculosis. A complete blood count may reveal an elevated white blood cell count (leukocytosis).

TREATMENT

Treatment for folliculitis consists of cleaning the infected area thoroughly with antibacterial soap and water; applying warm, wet compresses to promote vasodilation and drainage from the lesions; topical antibiotics such as mupirocin ointment and, in extensive infection or if a furuncle or carbuncle has developed, systemic antibiotics. Use sensitivity results to guide therapy, but begin treatment before receiving results. Furunculosis and carbunculosis may also require incision and drainage of ripe lesions if the lesions don’t drain after the application of warm, wet compresses. They may also require topical antibiotics after drainage.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Care for patients with folliculitis, furunculosis, and carbunculosis is basically supportive and emphasizes teaching the patient scrupulous

personal and family hygiene measures. Taking the necessary precautions to prevent spreading infection is also an important part of care.

personal and family hygiene measures. Taking the necessary precautions to prevent spreading infection is also an important part of care.

Caution the patient never to squeeze a boil because this may cause it to rupture into the surrounding area.

Advise the patient with recurrent furunculosis to have a physical examination because an underlying disease, such as diabetes or human immunodeficiency virus, may be present.

Trauma resulting from such hairstyles as cornrowing (gathering the hair into tight braids or tufts) can cause folliculitis.

To avoid spreading bacteria to family members, urge the patient not to share towels and washcloths. Tell him that these items should be laundered in hot water before being reused. The patient should change his clothes and bedsheets daily, and these also should be washed in hot water. Encourage the patient to change dressings frequently and to discard them promptly in paper bags.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), also known as Ritter’s disease or Ritter-Lyell syndrome, is marked by epidermal erythema, peeling, and necrosis that give the skin a scalded appearance. This severe skin disorder follows a consistent pattern of progression, and most patients recover fully. Mortality is 2% to 3%.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The causative organism in SSSS is group 2 Staphylococcus aureus, primarily phage type 71, which produces exotoxins that cause detachment of the epidermis. Predisposing factors may include impaired immunity and renal insufficiency—present to some extent in the normal neonate because of immature development of these systems.

SSSS is most prevalent in infants age 1 to 3 months but may develop in children. It’s uncommon in adults.

COMPLICATIONS

Fluid and electrolyte loss

Sepsis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

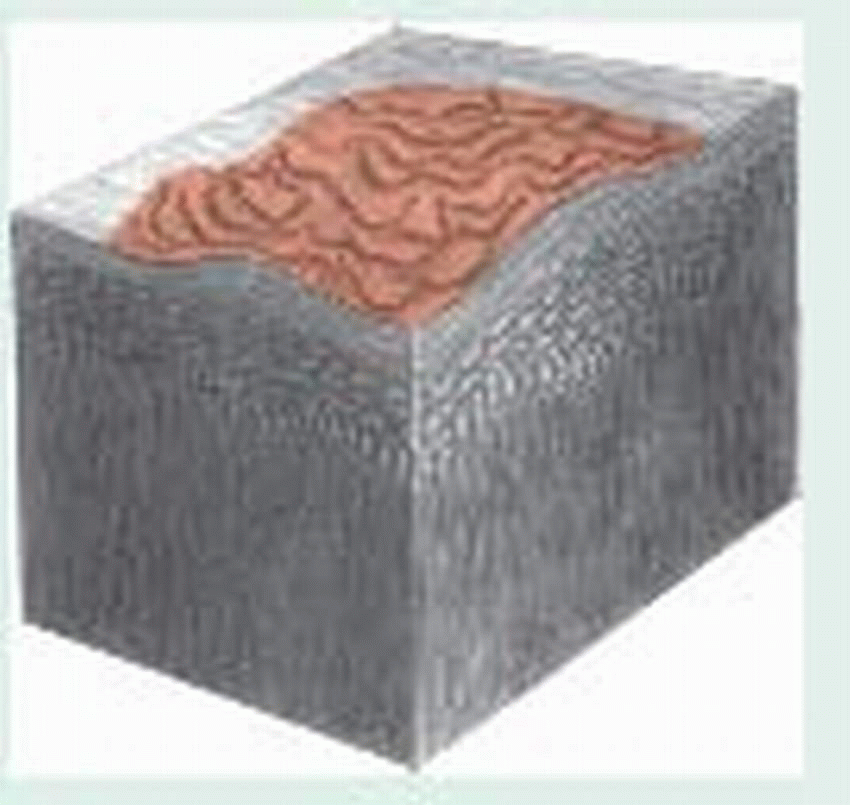

SSSS can usually be traced to a prodromal upper respiratory tract infection, possibly with concomitant purulent conjunctivitis. Cutaneous changes progress through three stages:

Erythema: Erythema, which may begin diffusely or as a scarlatiniform rash, usually becomes visible around the mouth and other orifices and may spread in widening circles over the entire body surface. The skin becomes tender; Nikolsky’s sign (sloughing of the skin when friction is applied) may appear.

Exfoliation (24 to 48 hours later): In the more common, localized form of this disease, superficial erosions with a red, moist base and minimal crusting occur, generally around body orifices, and may spread to exposed areas of the skin. (See Identifying staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, page 670.) In the more severe forms of this disease, large, flaccid bullae erupt and may spread to cover extensive areas of the body. These bullae eventually rupture, revealing sections of denuded skin; mucous membranes are spared.

Desquamation: In this final stage, affected areas dry up, and powdery scales form. Normal skin replaces these scales in 5 to 7 days.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis requires careful observation of the three-stage progression of this disease. Results of exfoliative cytology and biopsy aid in differential diagnosis, ruling out erythema multiforme and drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis, both of which are similar to SSSS.

Isolation of group 2 S. aureus on cultures of skin lesions confirms the diagnosis. However, skin lesions sometimes appear sterile.

TREATMENT

Treatment includes systemic antibiotics, usually penicillinase-resistant penicillin. Severe cases require hospitalization and I.V. antibiotics. Oral antibiotics should be adequate for milder cases. Skin lubrication with a non-alcohol-based preparation is beneficial. Washing or bathing should be done sparingly. Replacement measures to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance are necessary.

Hospital admission is appropriate for neonates and young children with extensive sloughing.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Carefully monitor intake and output to assess fluid and electrolyte balance. In severe cases, I.V. fluid replacement may be necessary.

Check vital signs. Be especially alert for a sudden rise in temperature, indicating sepsis, which requires prompt, aggressive treatment.

Maintain skin integrity. Use strict sterile technique to preclude secondary infection, especially during the exfoliative stage, because of open lesions. To prevent friction and sloughing of the skin, leave affected areas uncovered or loosely covered. Place cotton between severely affected fingers and toes to prevent webbing.

Gently débride exfoliated areas, especially those that have become necrotic.

Reassure the parents that complications are rare and residual scars are unlikely.

Provide special care for the neonate, if required, including placement in a warming infant incubator to maintain body temperature and provide isolation.

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Tinea versicolor

A chronic, superficial, fungal infection, tinea versicolor (also known as pityriasis versicolor) may produce a multicolored rash, commonly on the upper trunk. Recurrence is common.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The agent that causes tinea versicolor is Pityrosporum orbiculare, also known as P. ovale and Malassezia furfur. Whether this condition is infectious or merely a proliferation of normal skin fungi is uncertain. Tinea versicolor is more common in hot climates—tropical countries or in those with high humidity—and is associated with increased sweating. It usually affects adolescents and young men when sebaceous gland activity is at its highest.

COMPLICATION

♦ Secondary bacterial infections

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Tinea versicolor typically produces raised or macular, round or oval, slightly scaly lesions on the upper trunk, which may extend to the lower abdomen, neck, arms, groin, thigh, genitalia and, rarely, the face. These lesions are usually tawny but may range from hypopigmented (white) patches in dark-skinned patients to hyperpigmented (brown) patches in fair-skinned patients. Some areas don’t tan when exposed to sunlight, causing the cosmetic defect for which most people seek medical help. Inflammation, burning, and itching are possible but are usually absent.

DIAGNOSIS

Visualization of blue-green fluorescent lesions during Wood’s light examination strongly suggests tinea versicolor. However, if the patient has recently showered, this fluorescence may not show because the chemical that causes fluorescence is water-soluble.

Microscopic examination of skin scrapings prepared in potassium hydroxide solution confirms the disorder by showing hyphae, clusters of yeast, and large numbers of variously sized spores (a combination referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs”).

TREATMENT

The most economical and effective treatment is selenium sulfide lotion 2.5% applied once a day for 7 days. It’s left on the skin for 10 minutes, then rinsed off thoroughly. In persistent cases, therapy may require a single 12- or 24-hour application of this lotion, repeated once a week for 4 weeks. Either treatment may cause temporary redness and irritation.

Other treatments include sodium thiosulfate 25% solution, applied twice daily to affected areas for 2 to 4 weeks; sulfur salicylic shampoo applied as a lotion at bedtime each night and washed off each morning for 2 weeks; zinc pyrithione shampoo 1% lathered into affected areas for 5 minutes before showering, and repeated every day for 2 weeks; or imidazole antifungal agents applied twice daily for 2 weeks.

Ketoconazole and other azole-based creams, such as topical ketoconazole, may be applied once or twice daily for 2 weeks. Oral ketoconazole or another oral azole-based medication, such as fluconazole, may be used if the patient has extensive disease that fails to respond to other therapies.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Instruct the patient to apply selenium sulfide lotion as ordered. Tell him that this medication may cause temporary adverse effects.

Assure the patient that once his fungal infection is cured, discolored areas will gradually blend in after exposure to the sun or ultraviolet light.

Because recurrence of tinea versicolor is common, advise the patient to watch for new areas of discoloration.

Teach the patient proper hand-washing technique, and encourage good personal hygiene.

Provide written instructions for using prescribed medications. Tell the patient to contact the physician if adverse reactions occur.

Stress the importance of not scratching or picking lesions to avoid the risk of skin breaks and secondary bacterial infections.

Encourage the patient to avoid overexposure to heat and humidity.

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytosis, commonly called tinea, may affect the scalp (tinea capitis), body (tinea corporis),

nails (tinea unguium), hands (tinea manuum), feet (tinea pedis), groin (tinea cruris), and bearded skin (tinea barbae). With effective treatment, the cure rate is very high, although about 20% of infected people develop chronic conditions.

nails (tinea unguium), hands (tinea manuum), feet (tinea pedis), groin (tinea cruris), and bearded skin (tinea barbae). With effective treatment, the cure rate is very high, although about 20% of infected people develop chronic conditions.

Athlete’s foot

Dermatophytosis of the feet (tinea pedis) is popularly called athlete’s foot. This infection causes macerated, scaling lesions, which may spread from the interdigital spaces to the sole. Diagnosis must rule out other possible causes, such as eczema, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and maceration by tight, ill-fitting shoes.

|

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Tinea infections (except for tinea versicolor) result from dermatophytes (fungi) of the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton. Transmission can occur through contact with infected lesions, household cats and dogs, and soiled or contaminated articles, such as shoes, towels, or shower stalls.

Tinea infections are prevalent in the United States. They’re more common in males than in females.

COMPLICATIONS

Hair or nail loss

Secondary bacterial or candidal infections

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Lesions vary in appearance depending on the site of invasion (inside or outside the hair shaft), duration of infection, level of host resistance, and amount of inflammatory response. Tinea capitis ranges in appearance from broken-off hairs with little scaling to severe painful, inflammatory, pus-filled masses (kerions) covering the entire scalp. Partial hair loss occurs in all cases. The cardinal clue is broken-off hairs.

Tinea corporis produces flat lesions on the skin at any site except the scalp, bearded skin, hands, or feet. These lesions may be dry and scaly or moist and crusty; as they enlarge, their centers heal, causing the classic ring-shaped appearance. In tinea unguium (onychomycosis), infection typically starts at the tip of one or more toenails (fingernail infection is less common) and produces gradual thickening, discoloration, and crumbling of the nail, with accumulation of subungual debris. Eventually, the nail may be destroyed completely.

Tinea pedis, or athlete’s foot, causes scaling and blisters between the toes. Severe infection may result in inflammation, with severe itching and pain on walking. A dry, squamous inflammation may affect the entire sole. (See Athlete’s foot.) Tinea manuum produces scaling patches and hyperkeratosis on the palmar surface. It’s usually unilateral and is associated with tinea pedis. Tinea cruris (jock itch) produces red, raised, sharply defined, itchy or burning lesions in the groin that may extend to the buttocks, inner thighs, and the external genitalia. Warm weather, obesity, and tight clothing encourage fungus growth. Tinea barbae is an uncommon infection that affects the bearded facial area of men.

DIAGNOSIS

Microscopic examination of lesion scrapings prepared in potassium hydroxide solution will reveal branching fungal hyphae. Gently heating the slide helps separate epithelial cells and hyphae. Lowering the microscope condenser and dimming the light make hyphae easier to identify, as does adding a drop of ink to the potassium hydroxide.

Other diagnostic procedures include Wood’s light examination (useful in only about 5% of cases of tinea capitis) and culture of the infecting organism, which is important for identifying hair and nail fungal infections.

TREATMENT

Tinea infections respond to a wide variety of medications. Typically, infections of the skin (hands, body, feet, and groin) require only topical therapy. Infections of the hair and nails, skin infections causing chronic thickening of the skin, and other unresolving infections require oral antifungal therapy.

Topical preparations are commonly azolebased, though other preparations are available. Oral therapy includes azole-based medications and terbinafine. Griseofulvin is falling out of favor because newer products are easier to use and have a shorter duration of therapy.

Caution must be taken when using systemic antifungals: liver enzyme levels must be monitored before and throughout treatment if therapy is expected to extend more than 2 months, and chronic medications must be monitored because of the antifungal’s potential effect on blood levels.

Treatment should continue from several days to 2 weeks after lesions have resolved. Topical agents with soothing and cooling effects may be used with systemic therapy for infections with severe itching and burning; they may be discontinued when the immediate discomfort resolves.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Management of tinea infections requires medication compliance, observation for sensitivity reactions, observation for secondary bacterial infections, and patient teaching. Specific care varies by site of infection.

For tinea barbae: Suggest that the patient let his beard grow (whiskers may be trimmed with scissors, not a razor). If the patient insists that he must shave, advise him to use an electric razor instead of a blade.

For tinea capitis: If the condition worsens, discontinue medications and notify the physician. Use good hand-washing technique, and teach the patient to do the same. Spores of tinea capitis are shed in the air around an infected patient or may spread on contaminated clothing and other personal articles. To prevent spread of infection to others, advise him to wash his towels, bedclothes, and combs frequently in hot water and to avoid sharing them. Suggest that family members be checked for tinea capitis.

For tinea corporis: Use abdominal pads between skin folds for the patient with excessive abdominal girth; change pads frequently. Check the patient daily for excoriated, newly denuded areas of skin. Apply wet Burow’s compresses two or three times daily to decrease inflammation and help remove scales.

For tinea cruris: Instruct the patient to dry the affected area thoroughly after bathing and to evenly apply antifungal powder after applying the topical antifungal agent. Advise him to wear loose-fitting clothing, which should be changed frequently and washed in hot water.

For tinea pedis: Encourage the patient to expose his feet to air whenever possible, and to wear sandals or leather shoes and clean, white cotton socks. Instruct the patient to wash his feet twice daily and, after drying them thoroughly, to apply antifungal cream followed by antifungal powder to absorb perspiration and prevent excoriation. Tell him to allow his shoes to dry out by alternating pairs every other day. Also tell him to wear shower shoes when using public facilities.

For tinea unguium: Keep nails short and straight. Gently remove debris under the nails with an emery board. Prepare the patient for prolonged therapy.

PARASITIC INFESTATIONS

Scabies

A common skin infection, scabies results from infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis (itch mite), which provokes a sensitivity reaction. It’s transmitted through skin or sexual contact.

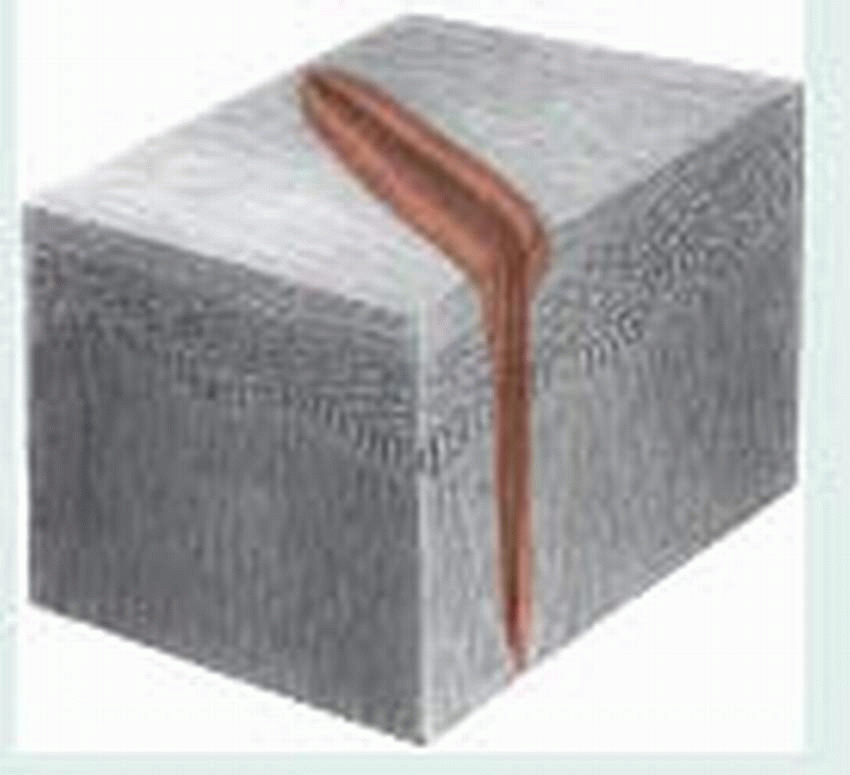

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

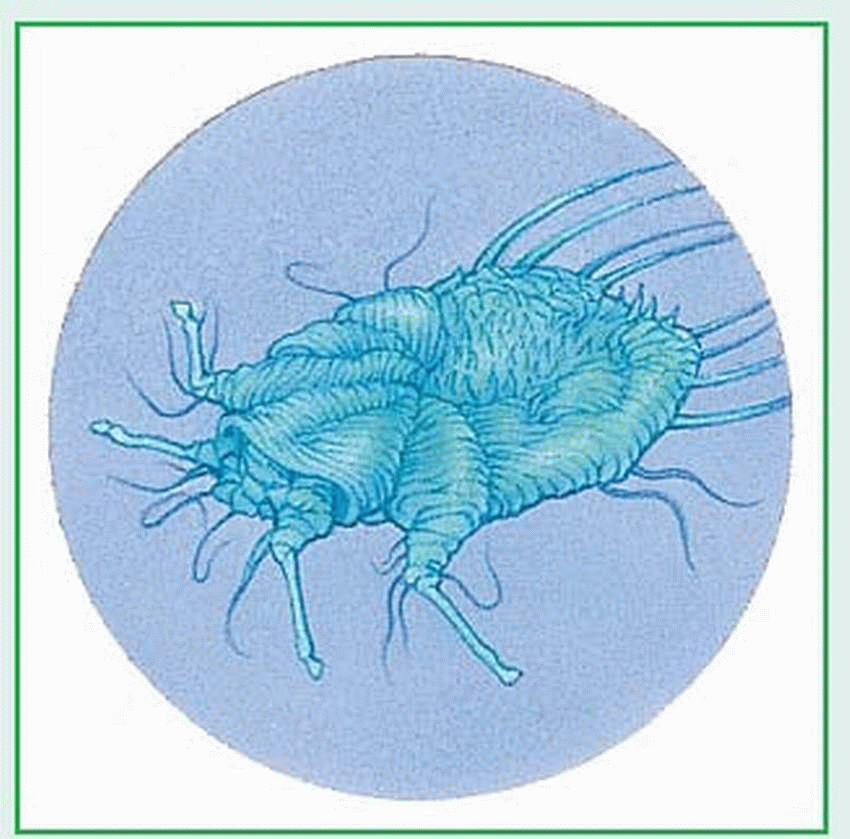

Mites can live their entire life cycles in the skin of humans, causing chronic infection. (The adult mite can survive without a human host for only 2 or 3 days.) The female mite burrows into the skin to lay her eggs, from which larvae emerge to copulate and then reburrow under the skin. (See Scabies: Cause and effect, page 674.)

Scabies occurs worldwide, primarily in environments marked by overcrowding and poor hygiene, and can be endemic.

COMPLICATIONS

Excoriation

Tissue trauma

Secondary bacterial infection

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Typically, scabies causes itching, which intensifies at night. Characteristic lesions are usually excoriated and may appear as erythematous nodules. These threadlike lesions are approximately 1 cm long and generally occur between fingers, on flexor surfaces of the wrists, on elbows, in axillary folds, at the waistline, on nipples and buttocks in females, and on genitalia in males.

In infants, the burrows (lesions) may appear on the head and neck.

DIAGNOSIS

Visual examination of the contents of the scabietic burrow may reveal the itch mite. If not, a drop of mineral oil placed over the burrow, followed by

superficial scraping and examination of expressed material under a low-power microscope, may reveal ova or mite feces. However, excoriation or inflammation of the burrow often makes such identification difficult. If diagnostic tests offer no positive identification of the mite and if scabies is still suspected (for example, if family members and close contacts of the patient also report itching), skin clearing that occurs after a therapeutic trial of a pediculicide confirms the diagnosis.

superficial scraping and examination of expressed material under a low-power microscope, may reveal ova or mite feces. However, excoriation or inflammation of the burrow often makes such identification difficult. If diagnostic tests offer no positive identification of the mite and if scabies is still suspected (for example, if family members and close contacts of the patient also report itching), skin clearing that occurs after a therapeutic trial of a pediculicide confirms the diagnosis.

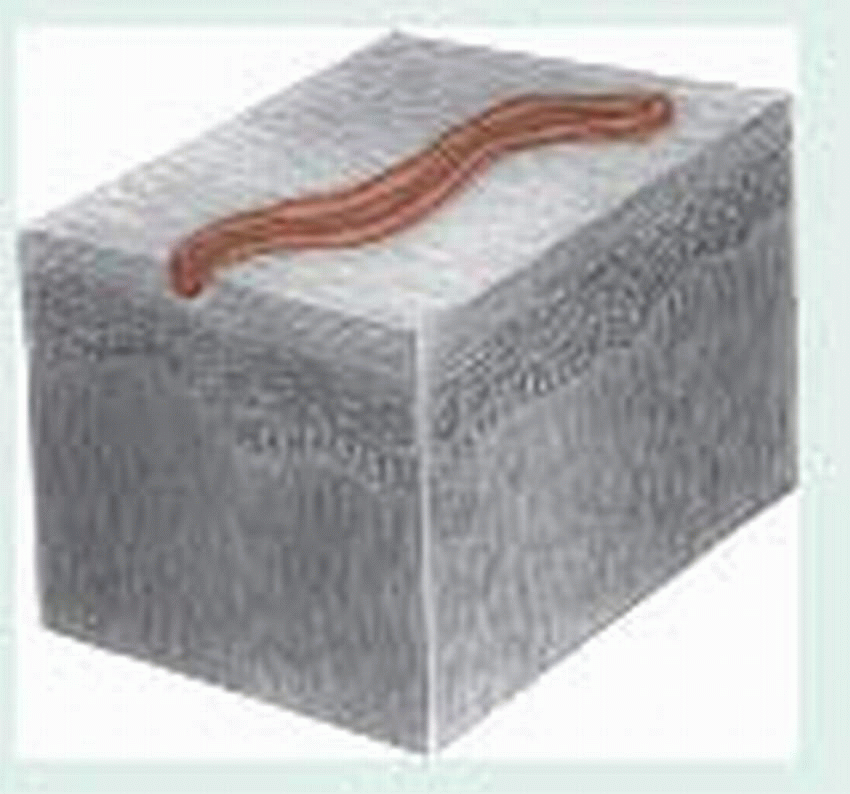

Scabies: Cause and effect

Infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei—the itch mite—causes scabies. This mite (shown enlarged below) has a hard shell and measures a microscopic 0.1 mm. The illustration below shows the erythematous nodules with excoriation that appear in patients with scabies. These lesions are usually highly pruritic.

|

|

TREATMENT

Generally, treatment for scabies consists of application of a pediculicide—permethrin, lindane cream, or crotamiton—in a thin layer over the entire skin surface from the neck down. Lindane and permethrin are left on the skin for 8 to 12 hours. Crotamiton is applied nightly for 2 consecutive nights and washed off 24 hours after the second application. To make certain that all areas have been treated, this application should be repeated in about 1 week. Oral ivermectin is also an effective treatment for scabies.

Lindane is an effective scabicide and, when used properly, may be applied safely to children, but shouldn’t be used in children younger than age 2 or pregnant or nursing mothers because of potential neurologic toxicity. It also shouldn’t be applied immediately after a shower. A 6% to 10% solution of sulfur in petrolatum may be used if patients object to using lindane, but they should be advised that sulfur is messy and odorous.

Persistent pruritus (from mite sensitization or contact dermatitis) may develop from repeated use of pediculicides rather than from continued infection. An antipruritic emollient, topical steroid, or oral antihistamine can reduce itching; intralesional steroids may resolve erythematous nodules.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Instruct the patient to apply permethrin, crotamiton, or lindane cream or lotion from the neck down, covering his entire body. He must wait 15 minutes before dressing and avoid bathing for 8 to 12 hours or longer, depending on the treatment used. Contaminated clothing and linens must be washed in hot water or dry cleaned.

Tell the patient not to apply lindane cream if his skin is raw or inflamed. Advise him that if skin irritation or hypersensitivity reaction develops, he should notify the physician immediately, discontinue using the drug, and thoroughly wash it off his skin.

Suggest to the patient that his family members and other close personal contacts be checked for possible symptoms.

If a hospitalized patient has scabies, prevent transmission to other patients. Practice good hand-washing technique or wear gloves when touching the patient; observe wound and skin precautions for 24 hours after treatment with a pediculicide; gas autoclave blood pressure cuffs before using them on other patients; isolate linens until the patient is noninfectious; and thoroughly disinfect the patient’s room after discharge.

Cutaneous larva migrans

Cutaneous larva migrans (CLM), also known as creeping eruption, is a skin reaction to

infestation by nematodes (hookworms or roundworms) that usually infect dogs and cats. Eruptions associated with cutaneous larva migrans clear completely with treatment.

infestation by nematodes (hookworms or roundworms) that usually infect dogs and cats. Eruptions associated with cutaneous larva migrans clear completely with treatment.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Under favorable conditions—warmth, moisture, sandy soil—hookworm or roundworm ova present in feces of affected animals (such as dogs and cats) and hatch into larvae, which can then burrow into human skin on contact. After penetrating its host, the larva becomes trapped under the skin, unable to reach the intestines to complete its normal life cycle.

The parasite then begins to move, producing the peculiar, tunnel-like lesions that are alternately meandering and linear, reflecting the nematode’s persistent and unsuccessful attempts to escape its host.

In the United States, CLM is second to pinworm in infestation.

COMPLICATIONS

Cellulitis

Excoriation

Secondary bacterial infection

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

A transient rash, tingling or, possibly, a small vesicle appears at the point of penetration, usually on an exposed area that has come in contact with the ground, such as the feet, legs, or buttocks. The incubation period is typically 1 to 6 days. The parasite may be active almost as soon as it enters the skin. Local pruritus begins within hours following penetration.

As the parasite migrates, it etches a noticeable thin, raised, red line on the skin, which may become vesicular and encrusted. Pruritus quickly develops, often with crusting and secondary infection following excoriation. Onset is usually characterized by slight itching that develops into intermittent stinging pain as the thin, red lines develop. The larva’s apparently random path can cover from 1 mm to 1 cm a day. Penetration of more than one larva may involve a much larger area of the skin, marking it with many tracks.

DIAGNOSIS

Characteristic migratory lesions strongly suggest cutaneous larva migrans. A thorough patient history usually reveals contact with warm, moist soil within the past several months. A skin biopsy may reveal larva in the subbasal layer.

TREATMENT

Topical application of thiabendazole, ivermectin, or albendazole is effective. The suspension is applied to lesions and the immediate surrounding areas four times daily for 1 week. Oral thiabendazole given in two divided doses for 3 to 5 days is effective. Oral ivermectin and albendazole are equally effective. Tell the patient that adverse effects of systemic thiabendazole include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and dizziness.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree