17 Skin disease

Skin disease is common. Surveys in Europe suggest that approximately 1 in 7–10 of all visits to a primary care physician is for a skin problem. Consultations for skin disease are becoming more common as the absolute incidence of many diseases (e.g. skin cancer, atopic dermatitis) has increased. In addition, the therapeutic options for diseases previously viewed as untreatable have increased and awareness of these therapies is spreading as patients take a greater interest in their health.

A glossary of dermatological words is shown in Box 17.1.

17.1 TERMS USED TO DESCRIBE SKIN LESIONS ![]()

| Primary lesions | |

| Macule | A small flat area of altered colour, e.g. freckle |

| Papule | A discrete raised lesion, which may be coloured; called a nodule if >1 cm |

| Plaque | A raised area of skin with a flat top, typically several cm across; often scaly |

| Vesicle, bulla | A small (∼several mm)/larger (∼several cm) blister, respectively |

| Pustule | A focal visible accumulation of pus in the skin; usually yellow or green |

| Abscess | A localised collection of pus in a cavity, >1 cm in diameter |

| Weal | An evanescent dermal collection of fluid; the fluid is diffuse, unlike in a blister |

| Papilloma | A projecting nipple-like mass, e.g. skin tag |

| Petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis | Petechiae are flat, pinhead-sized macules of extravascular blood in the dermis; larger ones (purpura) may be palpable; deeper bleeding causes an ecchymosis |

| Burrow | A linear or curvilinear papule, caused by a burrowing scabies mite |

| Comedone | A plug of keratin and sebum in a dilated pilosebaceous orifice |

| Telangiectasia | Visible dilatation of small cutaneous blood vessels |

| Secondary lesions (which evolve from primary lesions) | |

| Scale | A flake arising from the stratum corneum, e.g. psoriasis |

| Crust | Exudate of blood or serous fluid, e.g. eczema or tissue fluid |

| Ulcer | An area from which the epidermis and the upper part of the dermis have been lost |

| Excoriation | Damage resulting from scratching; usually a linear ulcer or erosion |

| Erosion | An area of skin denuded by complete or partial loss of the epidermis |

| Fissure | A deep, slit-shaped ulcer, e.g. irritant dermatitis of the hands |

| Sinus | A cavity or channel that permits the escape of pus or fluid |

| Scar | Permanent fibrous tissue resulting from healing |

| Atrophy | Loss of substance due to diminution of the epidermis, dermis or subcutaneous fat |

| Stria | A streak-like, atrophic, pink/purple/white lesion in the connective tissue |

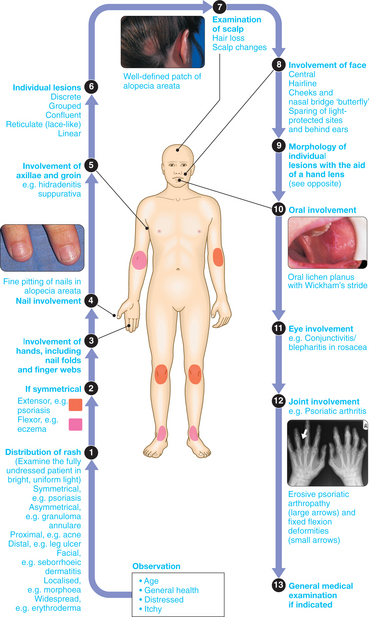

CLINICAL EXAMINATION IN SKIN DISEASE

ITCH (PRURITUS)

THE SCALY RASH (PAPULOSQUAMOUS ERUPTIONS)

A common presenting complaint in general practice is an eruptive scaly rash sometimes associated with itching. Causes are summarised in Box 17.2.

URTICARIA (NETTLE RASH, HIVES)

Urticaria refers to an area of focal dermal oedema secondary to a transient increase in capillary permeability, largely mediated by mast cell degranulation. The principal mediator released is histamine, which explains the efficacy of H1-blocking drugs in the management of this condition. On certain body sites such as the lips or hands the oedema spreads and is traditionally referred to as angioedema. By definition the swelling lasts <24 hrs. Urticarial vasculitis has a similar clinical presentation but lesions last >24 hrs.

Most cases are idiopathic but physical, drug-induced, infection-related and autoimmune forms exist (Box 17.3).

Clinical assessment

A directed history is still the best way to elicit any causes or precipitants of urticaria. A record of possible allergens, including drugs (see Box 17.9), should be determined. A family history must be sought in cases of angioedema, in order to determine the likelihood of a C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency. Dermographism may be elicited on examination.

17.9 DRUG ERUPTIONS AND SOME DRUGS WHICH MAY CAUSE THEM ![]()

| Reaction pattern | Clinical features | Examples of drugs commonly responsible |

|---|---|---|

| Toxic erythema | Erythematous plaques, morbilliform rash | Antibiotics, sde, thiazides, pbz, PAS |

| Urticaria | Itchy weals, sometimes with angioedema | Salicylates, codeine, antibiotics, dextran, ACEI |

| Erythema and scaling | Scaly, pink/red papules, varying sizes | Antibiotics, anticonvulsants, ACEI, gold, penicillamine |

| Allergic vasculitis | Painful palpable purpura with ulcers | Sde, pbz, indometacin, phenytoin, o.c. |

| Erythema multiforme | Target-like lesions and bullae on limbs | Sde, pbz, barbiturates |

| Purpura | Exclude thrombocytopenia, coagulation defect | Thiazides, sde, pbz, sulphonylureas, barbiturates, quinine |

| Bullous eruptions | Sometimes with erythema and purpura | Barbiturates, penicillamine, nalidixic acid |

| Exfoliative dermatitis | Universal redness and scaling, shivering | Pbz, PAS, isoniazid, gold |

| Fixed drug eruptions | Erythematous, occasionally bullous plaques | Tetracyclines, quinine, sde, barbiturates |

| Acneiform eruptions | Rash resembles acne | Lithium, o.c., steroids, anti-TB drugs, anticonvulsants |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | Rash resembles scalded skin | Barbiturates, phenytoin, pbz, penicillin |

| Hair loss | Diffuse | Cytotoxics, acitretin, anticoagulants, antithyroid drugs, o.c. |

| Hypertrichosis | Diazoxide, minoxidil, ciclosporin | |

| Photosensitivity | Rash limited to exposed skin | Thiazides, tetracyclines, phenothiazines, sde, psoralens |

ACEI = ACE inhibitors; sde = sulphonamides; o.c. = oral contraceptives; pbz = phenylbutazone; PAS = para-aminosalicylic acid.

Investigations

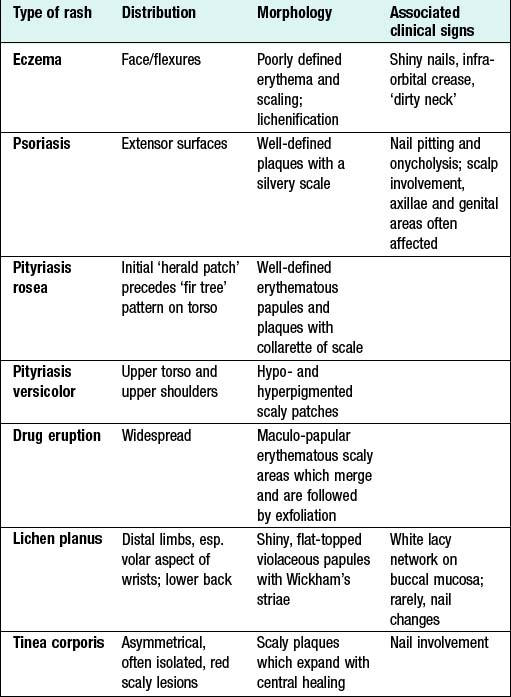

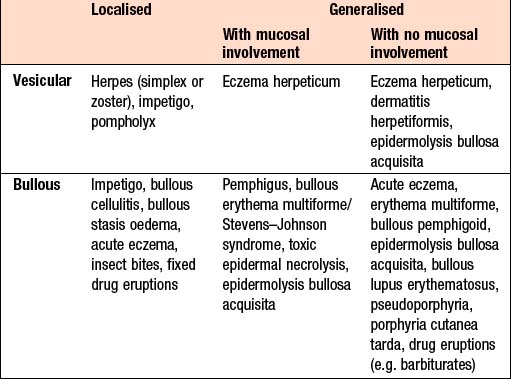

BLISTERS

Clinical assessment

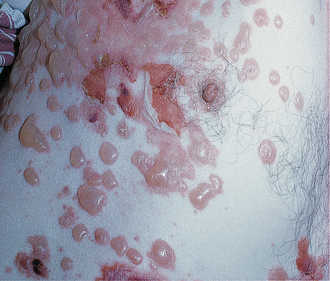

Acquired forms of blistering: These are common in childhood and adulthood (Box 17.4), and may be infectious in origin (e.g. staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome), drug-related, metabolic (e.g. porphyria), or part of another primary skin complex such as acute eczema or pompholyx. Toxic epidermal necrolysis may be life-threatening, can occur at any age and is often due to drugs. Loss of skin compromises fluid balance and thermoregulation and leads to severe pain and risk of infection. Intensive care is often required.

Autoimmune blistering diseases (Box 17.5): These are more common in later life, with the exception of dermatitis herpetiformis and pemphigus gestationis which occur in younger patients. Diagnosis is based on clinical features and immunopathology of biopsies. Rarely, some of these conditions may be related to an underlying malignancy (e.g. paraneoplastic pemphigus, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita associated with lymphoma, multiple myeloma or inflammatory bowel disease). Patients with a suspected diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis should be investigated for coeliac disease.

LEG ULCERS

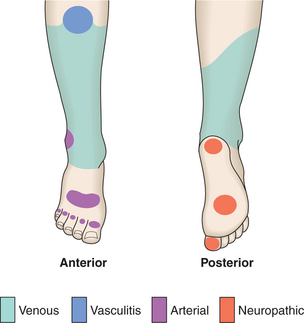

Ulceration of the skin is the complete loss of the epidermis and part of the dermis. There are numerous aetiologies, summarised in Box 17.6, but when present on the lower limb, ulceration is usually due to arterial or venous insufficiency. The site of the ulceration gives clues as to its aetiology (Fig. 17.2).

17.6 MAIN CAUSES OF LEG ULCERATION ![]()

| Venous hypertension | |

| Arterial disease | Atherosclerosis, vasculitis, Buerger’s disease |

| Small-vessel disease | Diabetes mellitus, vasculitis |

| Abnormalities of blood | Sickle-cell disease, cryoglobulinaemia, spherocytosis, immune complex disease |

| Neuropathy | Diabetes mellitus, leprosy, syphilis |

| Tumour | Squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Trauma | Injury, artefact |

LEG ULCERATION DUE TO VENOUS DISEASE

Clinical assessment

This is a common clinical problem in middle to old age. Clinical signs include:

Management

LEG ULCERATION DUE TO VASCULITIS

These ulcers start as painful, palpable, purpuric lesions and turn into small, punched-out ulcers. The involvement of larger vessels is heralded by painful nodules which evolve into intractable, deep, sharply demarcated ulcers. Management includes treatment of the underlying disorder as well as immunosuppression with, for example, systemic corticosteroids or cyclophosphamide.

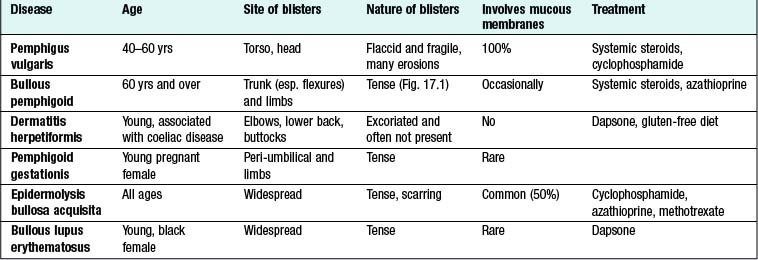

TOO LITTLE OR TOO MUCH HAIR

ALOPECIA

The term means nothing more than loss of hair and is a sign rather than a diagnosis. There are many causes and patterns, but an important distinction is whether the alopecia is scarring or non-scarring. The causes of alopecia are summarised in Box 17.7; the most common are discussed here.

17.7 CLASSIFICATION OF ALOPECIA ![]()

| Localised | Diffuse |

|---|---|

| Non-scarring | |

| Tinea capitis, alopecia areata, androgenetic alopecia, traumatic (trichotillomania, traction, cosmetic), syphilis | Androgenetic alopecia, telogen effluvium, metabolic, hypo- or hyperthyroidism, hypopituitarism, diabetes mellitus, HIV disease, nutritional deficiency, liver disease, post-partum, alopecia areata, syphilis |

| Scarring | |

| Developmental defects, discoid lupus erythematosus, herpes zoster, pseudopelade, tinea capitis/kerion, idiopathic | Discoid lupus erythematosus, radiotherapy, folliculitis decalvans, lichen planus pilaris |

Kerions are boggy, highly inflamed areas of tinea capitis and are usually caused by zoophilic fungi (from animals, e.g. cattle ringworm, T. verrucosum). Treatment is systemic, with oral terbinafine, griseofulvin or itraconazole. Topical therapy with an antifungal shampoo is recommended as an adjunct and arachis oil is used to remove crusting.

Investigations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree