Sils Cholecystectomy

Michael Tarnoff

Sajani Shah

Introduction

The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in 1987 by Phillipe Mouret in Lyon, France. Since that time, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the most commonly performed minimally invasive surgical procedure and has evolved as the gold standard for the treatment of symptomatic gallbladder disease. As minimally invasive continues to evolve, so does our quest to reduce the surgical footprint. The past 15 years have seen the introduction of less invasive approaches to conventional laparoscopy and have raised the debate of whether we can further enhance cosmesis and reduce postoperative pain or whether we have reached a point of diminishing returns.

Since early case reports focusing on feasibility first appeared in the late 1990s, single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) has reemerged as an attractive alternative to conventional minimally invasive surgery with real potential for improvements to patient outcomes. Regardless of nomenclature—SILS, laparoendoscopic single-site surgery, single-port access, natural orifice transumbilical surgery, transumbilical endoscopic surgery, single access surgery, and embryologic natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery—many have postulated that the performance of minimally invasive surgery through a single incision may emerge as a new standard by reducing postoperative pain and/or improving cosmesis.

Patient Preparation and Access

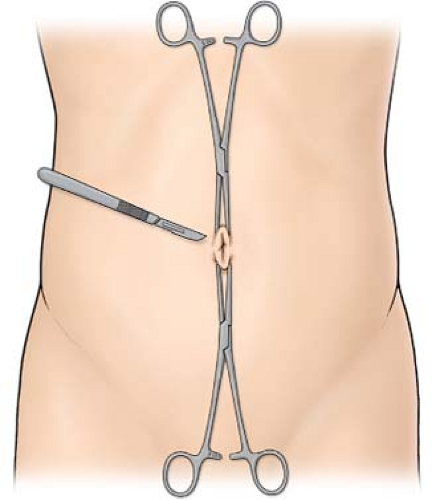

The operation is performed under general anesthesia. An orogastric or nasogastric tube is useful for de’ating the stomach and improving visualization during the procedure. The patient is placed in a supine position with both upper extremities abducted. The surgeon and the assistant both stand on the left side of the patient and the monitor is placed on the opposite side. Others have described utilizing the lithotomy position. The native rim of the umbilicus is encircled

with a marking pen. The umbilicus is everted by grasping its deepest point and pulling it anterior with a Kocher clamp (Fig. 1).

with a marking pen. The umbilicus is everted by grasping its deepest point and pulling it anterior with a Kocher clamp (Fig. 1).

Insertion of Commercially Available Single Ports

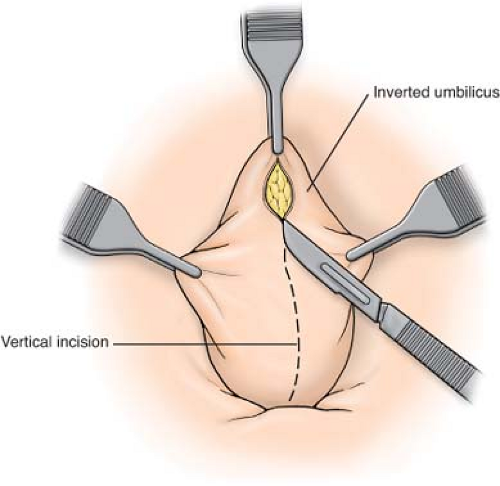

A 1.5- to 2-cm transumbilical incision is made in a horizontal fashion without extension of this incision beyond the outer limits of the umbilical folds or entry into the umbilicus itself (Fig. 2). The size of the incision will vary depending on the single-incision access port utilized.

Blunt dissection can be used to expose the base of the umbilicus. A fascial incision tailored to the access port can be made with a scalpel while lifting up the umbilicus. A hemostat or finger is gently advanced through the fascial incision to ensure that there are no attachments or adhesions. The commercial port is then inserted into the body cavity.

Port Insertion Using Multiple Trocars Through A Single Skin Incision

The alternative to accessing the peritoneal cavity is to use several low-profile, small-diameter head trocars through separate punctures through the fascia within the umbilicus. These trocars can be placed in a triangle formation. The three separate incisions made can be connected at the end of the procedure.

While lifting up on the umbilicus, a <1 cm fascial incision is made. A hemostat or finger is passed into the body cavity to free adhesions and ensure clearance. A 5- or 12-mm port can then be gently advanced into the peritoneal cavity under direct visualization. At least two additional 5-mm trocars can be placed medial and lateral from the initial port under direct visualization. These ports should be at least 1 cm away to prevent clashing of the instruments.

Gallbladder Retraction and Dissection of Calot’s Triangle

Pneumoperitoneum is established with a pressure of 15 mm Hg. The patient is then placed in reverse Trendelenburg position with a slight left-lateral decubitus in order to expose the surgical field. A 5- or 10-mm 45-degree standard scope is then inserted for visualization. The safety and feasibility of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy is dependent upon the surgeon’s ability to ergonomically and spatially establish triangulation of pathology. Modifications to graspers, scissors, electrocautery, and laparoscopes have now enhanced this possibility. The emergence of uniquely roticulating and articulating hand instruments have dramatically improved the surgeon’s abilities to achieve triangulation of pathology while avoiding clashing of the instruments and limited range of motion. We favor a mix of conventional straight instrumentation and these more novel highly flexible instruments to facilitate safe dissection and exposure.

Retraction of the Gallbladder

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree