Chapter 2 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Introduction

Most symptoms and many signs are usually described during the medical history interview when the patient pre-sents to the physician. Other signs are discovered during the physical examination and clinical work-up. The most important findings detected by physical examination are listed in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1 Clinical Findings That Can Be Noted During Physical Examination

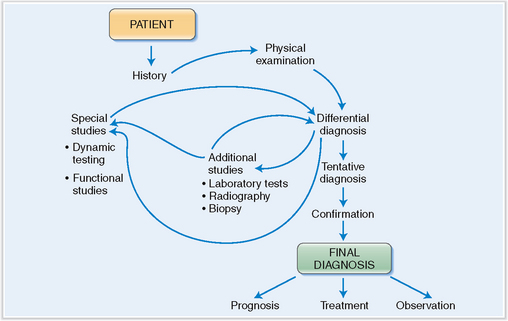

The ultimate significance of all signs and symptoms discovered during the initial work-up is not always obvious, and the physician must often use inductive and deductive reasoning in interpreting them. Often it is necessary to formulate one or more working hypotheses and develop a list of various similar conditions to be included in the differential diagnosis. Many of these conditions must be excluded by additional testing until the tentative diagnosis is reached (Fig. 2-1). This tentative diagnosis functions as a working hypothesis until confirmed by other means, which often include definitive or pathognomonic pathologic findings. Prior to instituting any therapy, it is desirable to make the definitive diagnosis formulated in terms of precise etiology, pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and underlying pathology.

The signs and symptoms of various diseases may be classified as systemic or centered on a specific organ system. The important and common systemic signs and symptoms are described here, but most of the organ system-centered signs and symptoms will be discussed in subsequent chapters. Table 2-2 contains a list of the most common systemic and organ-centered signs and symptoms encountered in general medical practice.

Table 2-2 Most Common Signs and Symptoms Encountered in General Medical Practice

| PHYSICAL | ||

| SYSTEMIC | LOCALIZED | PSYCHOLOGICAL/NEUROLOGIC/SENSORY |

| Fatigue | Pain | Anxiety |

| Fever | Headache | Depression |

| Weakness | Back pain and joint pain | Insomnia |

| Anorexia | Chest and abdominal pain | Irritability |

| Weight loss | Cough | Loss of mental prowess |

| Weight gain | Nasal discharge | Loss of consciousness |

| Swelling* | GI symptoms | Dizziness and vertigo |

| Itching and rash* | Shortness of breath | Gait and movement disorders |

| Bleeding* | Palpable “lumps and bumps” | Hearing loss |

| Visual problems | ||

* May be both systemic and localized. Note also that this classification includes certain entities that could belong to more than one rubric and that some physical signs and symptoms are actually manifestations of psychological/neurologic disturbances.

Fatigue

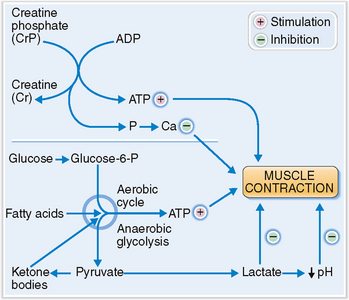

Fatigue, or tiredness, is the normal physiologic response to demanding exercise or any other prolonged physical or mental activity. Physiologically, it can be most easily measured in the muscles, which, when fatigued, cannot maintain a contraction or respond progressively slowly to stimuli, until finally no reaction can be elicited from them. In such cases the muscles are simply depleted of fuel in form of nutrients (e.g., glycogen) and energy-rich compounds like creatine phosphate or adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Fig. 2-2). The accumulation of lactic acid and the acidification of the internal milieu inhibit actin–myosin interaction and muscle cell contraction. Increased concentration of phosphorus in the cytosol affects the release of calcium from internal stores (e.g., sarcoplasmic reticulum), preventing its catalytic action on the contractile fibers.

Anorexia Lack of appetite sometimes associated with aversion to food.

Cachexia Generalized weakness, wasting, and weight loss caused by cancer or other debilitating chronic diseases.

Coma State of deep unconsciousness accompanied by a loss of responsiveness to external stimuli. The depth of coma can be graded; in the most severe form it is irreversible.

Edema Localized or generalized excessive accumulation of fluid in the interstitial spaces of various tissues or body cavities. When generalized it is called anasarca.

Fatigue Feeling of tiredness and inability to perform optimally. It occurs physiologically at the end of prolonged effort or as a sign of disease.

Fever (pyrexia) Increased body temperature over the upper limits of normal. It may be a physiologic response to endogenous or exogenous influences that accelerate the metabolism or raise the body temperature. Most often it is a consequence of diseases that produce endogenous pyrogens acting on the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center.

Headache (cephalalgia) Pain in the head caused by a variety of mechanisms affecting the intracranial or extracranial structures of the head.

Hemorrhage (bleeding) Escape of blood from the vessels into the tissues, hollow organs, or external environment.

Pain Unpleasant or distressing feeling based on a psychological reaction to sensory stimuli generated in specialized nerve endings in the skin, muscles, and many internal organs.

Sign Manifestation of a disease that can be recognized objectively by medical examination.

Symptom Manifestation of a disease recognized subjectively by the affected patient.

Syncope (faint, swoon) Temporary loss of consciousness related to a sudden onset of generalized cerebral ischemia.

Weight loss Voluntary or involuntary loss of body mass, empirically defined as exceeding 5% of the body weight over a 6-month period.

Fatigue is a common sign of disease.

Fatigue related to systemic disease is usually mild or nonexistent in the morning but worsens during the day. It may be caused by hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, chronic heart disease, lung diseases, hematologic diseases such as anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome or multiple myeloma, cirrhosis, uremia, cancer, chronic infections, and autoimmune disorders, to mention the most important ones. Neuromuscular disorders, such as muscular dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease cause fatigue with muscle weakness. The most common organic causes of fatigue are listed in Table 2-3.

Table 2-3 Organic Causes of Fatigue

| CATEGORIES OF DISEASES | CLINICAL EXAMPLES |

| Cardiovascular | Congestive heart failure, MI |

| Respiratory | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma |

| Hematologic | Anemia, MDS, multiple myeloma |

| Endocrine | Hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, adrenal insufficiency |

| Hepatic | Cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis |

| Renal | Chronic renal failure |

| Neurologic/muscular | Myopathies, neuropathies, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis |

| Cancer | Any form of cancer can cause fatigue |

| Autoimmune | Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE |

| Other | Obesity, malnutrition, alcohol abuse, effects of medication, radiation therapy |

MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MI, myocardial infarction; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

The clinical diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome is made only if the symptoms last more than 6 months. Muscle and joint pain are common, and headache is a prominent complaint. The extent of fatigue worsens during the day and after exertion. Other symptoms include fever that comes and wanes, abdominal pain, muscle pain, and difficulty in concentrating or sleeping. Organic symptoms such as sore throat and enlargement of lymph nodes may suggest chronic infection or neoplasia, but detailed clinical studies usually cannot prove any structural abnormalities. The laboratory studies are usually noncontributory. The treatment should include supportive measures and should be planned for each person individually, but no treatment regimen devised to date has proved successful.

Weight Loss

Weight loss due to a loss of fluid is called dehydration.

Overall, weight loss can result under the following conditions:

Insufficient intake of food. The causes vary over a broad range from famine related to poverty, to voluntary reduction of food intake, or that resulting from psychiatric diseases such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia.

Insufficient intake of food. The causes vary over a broad range from famine related to poverty, to voluntary reduction of food intake, or that resulting from psychiatric diseases such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia.

Malabsorption of nutrients. This can occur, for example, in chronic pancreatitis, intestinal malabsorption syndromes, intestinal lymphoma, amyloidosis, scleroderma, and chronic liver disease.

Malabsorption of nutrients. This can occur, for example, in chronic pancreatitis, intestinal malabsorption syndromes, intestinal lymphoma, amyloidosis, scleroderma, and chronic liver disease.

Loss of metabolites and nutrients. Nutrients can be lost due to prolonged vomiting, diarrhea, or drainage through fistula tracts. In diabetes mellitus glucosuria and diarrhea may also cause a loss of metabolites, such as glucose loss in urine and protein loss in the stool.

Loss of metabolites and nutrients. Nutrients can be lost due to prolonged vomiting, diarrhea, or drainage through fistula tracts. In diabetes mellitus glucosuria and diarrhea may also cause a loss of metabolites, such as glucose loss in urine and protein loss in the stool.

Increased demand for nutrients and calories. An increased demand for nutrients and calories occurs physiologically during infancy and childhood, as well as during pregnancy. Pathologically increased demand may occur in the course of chronic infections, after burns, and in patients who have malignant tumors. Metabolic disorders such as hyperthyroidism cause hypermetabolism requiring more calories.

Increased demand for nutrients and calories. An increased demand for nutrients and calories occurs physiologically during infancy and childhood, as well as during pregnancy. Pathologically increased demand may occur in the course of chronic infections, after burns, and in patients who have malignant tumors. Metabolic disorders such as hyperthyroidism cause hypermetabolism requiring more calories.

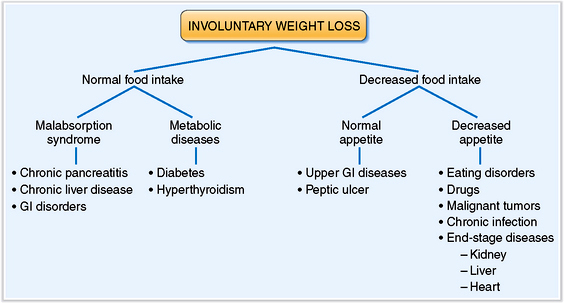

The initial work-up for a patient who complains of weight loss must first determine if the weight loss is voluntary or involuntary. In cases of involuntary weight loss, document not only the extent but also the duration of the loss and investigate the possible causes. Determine whether the food intake is normal or decreased (Fig. 2-3). If food intake is adequate the weight loss might be related to inadequate absorption or to excessive loss or utilization of calories caused by various metabolic diseases. On the other hand, if food intake is decreased, determine whether the patient has normal or decreased appetite and then ascertain the causes of these conditions.

Cachexia is characterized by involuntary weight loss caused by the complex effects of cancer or chronic diseases on the body.

Obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. Carcinoma of the stomach and esophagus may interfere with the ingestion of food. Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas may obstruct the common bile duct and prevent the influx of bile or pancreatic juices.

Obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. Carcinoma of the stomach and esophagus may interfere with the ingestion of food. Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas may obstruct the common bile duct and prevent the influx of bile or pancreatic juices.

Anorexia. Patients lose appetite, which in part could be due to a loss of taste for sweet, sour, and salty foods. Some patients, like those who have gastric or liver cancer, develop aversion to meat, whereas others develop a dislike for coffee or chocolate.

Anorexia. Patients lose appetite, which in part could be due to a loss of taste for sweet, sour, and salty foods. Some patients, like those who have gastric or liver cancer, develop aversion to meat, whereas others develop a dislike for coffee or chocolate.

Early satiety. Increased blood glucose due to poor utilization or low levels of insulin may suppress appetite. Increased plasma concentration of proteins and amino acids mobilized from the muscle may act on the satiety center and suppress appetite.

Early satiety. Increased blood glucose due to poor utilization or low levels of insulin may suppress appetite. Increased plasma concentration of proteins and amino acids mobilized from the muscle may act on the satiety center and suppress appetite.

Increased energy expenditure. The tumor acts as a parasite and may consume more energy than normal tissues. In addition, the competition for nutrients between the tumor and the host leads to metabolic disturbances in the host, including hypermetabolism, which, in turn, leads to an increased energetic inefficiency.

Increased energy expenditure. The tumor acts as a parasite and may consume more energy than normal tissues. In addition, the competition for nutrients between the tumor and the host leads to metabolic disturbances in the host, including hypermetabolism, which, in turn, leads to an increased energetic inefficiency.

Cytokines released in response to tumor growth. Tumor necrosis factor (also known as cachectin), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and many other cytokines could be responsible for anorexia, hypermetabolism, and many other metabolic abnormalities, such as muscle proteolysis and apoptosis.

Cytokines released in response to tumor growth. Tumor necrosis factor (also known as cachectin), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and many other cytokines could be responsible for anorexia, hypermetabolism, and many other metabolic abnormalities, such as muscle proteolysis and apoptosis.

Therapy. Weight loss is in many cases due to chemotherapy, known to cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, altered taste, and pain. Surgery could also cause increased weight loss by increasing energy expenditure or by affecting food intake.

Therapy. Weight loss is in many cases due to chemotherapy, known to cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, altered taste, and pain. Surgery could also cause increased weight loss by increasing energy expenditure or by affecting food intake.

Fever

Normal body temperature is under the control of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center.

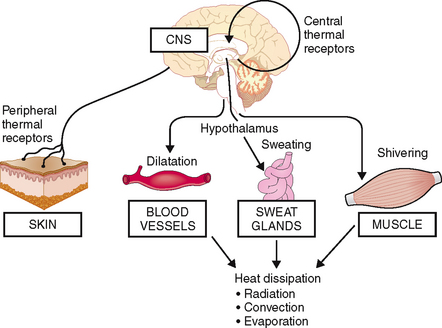

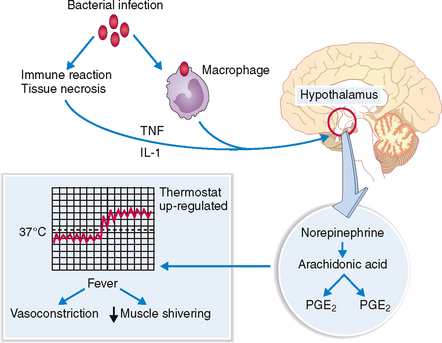

Heat generated in the course of various metabolic processes and normal action of muscles and other organs is dissipated mostly through the skin and some internal organs such as lungs and the upper aerodigestive system. The entire process of thermoregulation depends on the proper functioning of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center, which receives input from the peripheral sensors for cold and warm in the skin and central thermal receptors in the hypothalamus. Skin receptors respond to external temperature, whereas the central receptors respond to the temperature of the blood. Both signals are integrated and compared with the setting of the hypothalamic thermostat. If the temperature exceeds the upper limit set by the thermostat, signals are sent to the periphery to dissipate the heat. This occurs through the vasodilatation of dermal blood vessels, which fill with warm blood, allowing the blood to transmit the excess heat to the exterior of the body by radiation or convection. Central signals also activate sweat glands, stimulating heat loss by evaporation. Shivering of skeletal muscles may increase peripheral heat production (Fig. 2-4).

Fever results from action of endogenous pyrogens on the hypothalamic thermostat.

Endogenous pyrogens do not act directly on the thermoregulatory center. Instead, they act on the endothelial cells of a highly vascular part of the wall of the third ventricle, called organum vasculosum laminae terminalis (OVLT). Under the influence of pyrogens the endothelial cells of OVLT produce prostaglandin PGE2, which diffuses into the adjacent hypothalamus and, by acting on the thermoregulatory center, raises the set point for thermoregulation. The signals from the thermoregulatory center lead to vasoconstriction of dermal vessels, cessation of sweating, and shivering of muscles, thereby reducing the dissipation of heat (Fig. 2-5).

Fever can result from infections or noninfectious disease.

Fever is a common sign of infections, but it can occur in the course of many other diseases (Table 2-4). Thus it is customary to classify fever as infectious or noninfectious. If the cause cannot be identified, it is classified as fever of unknown origin (FUO).

Table 2-4 Common Causes of Fever

Fever of infectious origin. Almost any acute or chronic infectious disease may cause fever. As a rule, infection should be the first diagnosis considered in all febrile patients, especially if the fever is of sudden onset, associated with other signs of inflammation, and localizing symptoms point to a site of infection. Only after infection has been excluded as a possible cause is it advisable to consider other causes of fever.

Fever of unknown origin. For clinical purposes FUO is defined as temperature over 38.3°C (101°F) lasting at least 3 weeks, for which the cause could not be found after 1 week of intensive investigation. Most diseases that evade early diagnosis turn out to be either infectious or neoplastic. Even under the best of all possible conditions, the cause of fever cannot be determined in about 10% to 15% of patients.

Pain

Stimulation of the sensory nerve endings or nociceptors

Stimulation of the sensory nerve endings or nociceptors

Transmission of the afferent sensory nerve impulse

Transmission of the afferent sensory nerve impulse

Modulation of the impulse in the sensory centers

Modulation of the impulse in the sensory centers

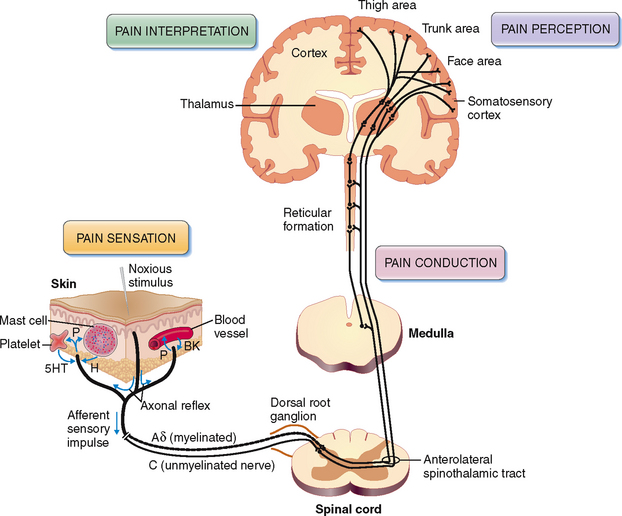

The pain pathway has two parts: the peripheral part, involving the nociceptors and sensory nerves, and a central part, involving the cortical centers (Fig. 2-6).

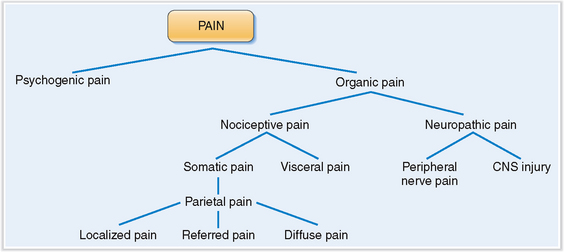

Pain can be classified as organic or psychogenic.

Because pain has both sensory and psychological components, it is best to classify it as predominantly organic or predominantly psychogenic (Fig. 2-7). Organic pain can be explained in terms of underlying pathology, whereas psychogenic pain eludes such explanation and its cause may be quite puzzling.

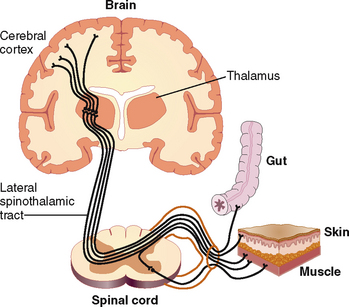

Organic pain resulting from excessive or prolonged stimulation of peripheral nerve endings is called nociceptive pain (Fig. 2-8). Nociceptive pain, which originates in the skin and subcutaneous tissues, typically corresponds to innervation of anatomic dermatomes and is called somatic pain. Somatic pain is typically sharp, severe, and pricking. Pain originating from the parietal peritoneum or pleura is known as parietal pain but in essence is identical to somatic pain. Parietal pain can be localized or diffuse. Localized pain, such as pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant in appendicitis, can pinpoint the nature of the disease that precipitates it. However, pain can also be referred to a site quite distant from the site of original pathology. Diffuse parietal pain is typically seen in peritonitis when the entire surface of the abdominal cavity is inflamed. Typically the patient tries not to move, and any movement, such as coughing or vomiting, exacerbates the pain. Pain originating from the nerve endings in internal organs is called visceral pain. Visceral pain is usually poorly localized and is most intensively felt in the midline of the abdomen or thorax. Pain is often dull, but it may also be colicky and cause a feeling described by the patients as gnawing or burning.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree