Stephanie J. Phelps

28-1. Key Points

■ Phenytoin can be mixed only with normal saline and should not be given faster than 50 mg/min.

■ Gabapentin and levetiracetam are not associated with any significant drug interactions.

■ As of September 2009, the following anticonvulsants carry a U.S. boxed warning: carbamazepine (aplastic anemia, dermatologic reactions); valproic acid (liver failure, teratogenicity, pancreatitis); felbamate (aplastic anemia, hepatic failure); and lamotrigine (serious rash). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warnings have been given for zonisamide and topiramate, which have been reported to cause oligohidrosis and hyperthermia. The FDA has found that 11 of the anticonvulsants are associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior or ideation.

■ Although absence seizures are frequently treated with ethosuximide or valproic acid (for patients ≥ 2 years of age), lamotrigine and topiramate are also used.

■ Carbapenems (e.g., imipenem) and normeperidine (a metabolite of meperidine that accumulates in renal failure) may cause seizures.

■ Carbamazepine undergoes autoinduction (i.e., it induces its own metabolism), and phenytoin has capacity-limited or saturable (i.e., Michaelis–Menten) pharmacokinetics.

■ Because of the potential for severe life-threatening liver toxicity, valproic acid is generally not used in a patient < 2 years of age.

■ There may be an association between folic acid deficiency and spina bifida; hence, all women with epilepsy who are of childbearing age should be on daily folic acid (1 mg).

■ Unless a patient is experiencing a life-threatening adverse effect, an anticonvulsant should not be abruptly discontinued.

■ Topiramate may cause significant weight loss, and valproic acid may cause significant weight gain.

■ Topiramate and zonisamide may cause kidney stones.

■ Patients with an allergy to sulfa medications should not be given zonisamide.

28-2. Study Guide Checklist

The following topics may guide your study of this subject area:

■ The two main types of seizures and the differences between the two

■ Drugs most often used as mono therapy in each of the two main types of seizures

■ Drugs most often used as adjunctive therapy in each of the two main types of seizures

■ Criteria for treatment, principles of treatment, and reasons for treatment failure of epilepsy

■ FDA black box warnings and the most prevalent adverse effects for the various classes of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs)

■ Important drug–drug interactions involving AEDs

■ Emergent treatment of status epilepticus

28-3. Epilepsy

Epilepsy occurs when neurons become depolarized and repetitively fire action potentials. It is involuntary and episodic. The term is applied after two unprovoked seizures. A seizure does not mean a person has epilepsy; however, epilepsy means a person has seizures. Anticonvulsants do not cure epilepsy.

Terminology

■ Aura: A subjective sensation or motor phenomenon that marks a seizure onset and is generally associated with sensations that are localized in a particular region of the brain

■ Automatisms: Purposeless movements seen with partial seizures

■ Postictal: Symptoms and signs seen after a seizure

Types of Epilepsy

There are two main types of epilepsy: partial seizures and generalized seizures.

Partial seizures

Partial seizures begin in one hemisphere of the brain. They are unilateral, asymmetric movements, generally associated with an aura. Complex partial seizures are accompanied by altered consciousness.

Drugs for new-onset partial seizures

See individual drug for specific indication information.

■ Monotherapy: Carbamazepine (drug of choice), lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, topiramate, valproic acid

■ Adjunctive therapy: Eslicarbazepine, gabapentin, lacosamide, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, phenobarbital, phenytoin, tiagabine, topiramate, valproic acid, zonisamide

Drugs for refractory partial seizures

See individual drug for specific indication information.

■ Monotherapy: Carbamazepine, felbamate, lamotrigine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, topiramate, valproic acid

■ Adjunctive therapy: Eslicarbazepine, ezogabine, felbamate, gabapentin, lamotrigine, lacosamide, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, phenobarbital, phenytoin, zonisamide

Generalized seizures

Generalized seizures begin simultaneously in both brain hemispheres. They are characterized by bilateral movements and have no aura.

Absence seizures

This type of generalized seizure has a sudden onset. It is brief (seconds) and characterized by a blank stare, upward rotation of the eyes, and lip smacking (confused with daydreaming). It has a three-per-second spike and wave on electroencephalography (EEG) and can be precipitated by hyperventilation.

Drugs

See individual drug for specific indication information.

Historically, ethosuximide has been the drug of choice. If a patient has both absence and generalized tonic–clonic seizures and is older than 2 years of age, many consider valproic acid to be the drug of choice. Although not labeled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), lamotrigine and topiramate are used.

Primary generalized tonic–clonic seizure

This type of seizure has two phases:

■ Tonic phase: Rigid, violent, sudden muscular contractions (stiff or rigid); crying or moaning; deviation of the eyes and head to one side; rotation of the whole body and distortion of features; suppression of respiration; falling to the ground; loss of consciousness; tongue biting; involuntary urination

■ Clonic phase: Repetitive jerks; cyanosis continues; foaming at the mouth; small grunting respirations between seizures, but deep respirations as all muscles relax at the end of the seizure

Drugs of choice

See individual drug for specific indication information.

■ Monotherapy: Carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, topiramate (≥ 2 years of age)

■ Adjunctive therapy: Lamotrigine, levetiracetam, topiramate, valproic acid

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) consists of myoclonic and generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Myoclonic seizures precede generalized tonic–clonic seizures, and both seizure types generally occur on awakening. Sleep deprivation and alcohol commonly precipitate JME.

Because JME has a genetic basis, lifelong treatment is required. Although not FDA labeled for this use, valproic acid, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, topiramate, or some combination of these agents is prescribed.

Other less common seizure types

Catamenial epilepsy

Catamenial epilepsy is associated with hormonal changes during menstruation and may be treated with acetazolamide.

Infantile spasms

Infantile spasms begin in the first 6 months of life. They occur in clusters, several times a day. Parents describe symptoms that resemble colic. Infantile spasms are associated with high mortality and morbidity.

This condition is treated with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) or oral steroids, vigabatrin, or valproic acid (> 2 years). Although not FDA labeled for this purpose, topiramate and zonisamide have been used.

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome

This syndrome accounts for as few as 1–4% of childhood epilepsies, most often appears between 2–6 years of age, and is frequently accompanied by mental retardation and behavior problems. It is characterized by different types of intractable seizures.

This condition is treated with combination anticonvulsants that include clobazam (> 2 years), felbamate (> 2 years), lamotrigine (> 2 years), rufinamide (≥ 4 years), and topiramate (≥ 2 years). Although not FDA labeled for this purpose, zonisamide has been used.

Post-traumatic epilepsy

These seizures occur following head trauma and may be treated prophylactically with phenytoin or fosphenytoin for a period of 7 days. Levetiracetam is also used for this purpose. Valproic acid should not be used because it has been associated with a greater likelihood of central nervous system (CNS) bleeding and a higher mortality rate in this population. If no seizures occur within 7 days, medication should be discontinued.

Etiologies for Epilepsy

■ Mechanical: Birth injuries, head trauma, tumors, vascular abnormalities (stroke)

■ Metabolic: Electrolyte disturbances (low sodium, elevated calcium); glucose abnormalities (low glucose); inborn errors of metabolism

■ Genetic: Benign familial neonatal seizures (chromosome 20), JME (chromosome 6), Baltic myoclonic (chromosome 21)

■ Other: Fever, infection

■ Drugs: These include, but are not limited to, the following:

• Recreational drugs such as alcohol, cocaine and freebase cocaine, ephedra, methylphenidate, narcotics

• Carbapenems (imipenem), lindane, local anesthetics (lidocaine), metoclopramide, theophylline, tricyclic antidepressants

• Meperidine (the metabolite normeperidine can cause seizures in patients with renal failure who receive normal doses)

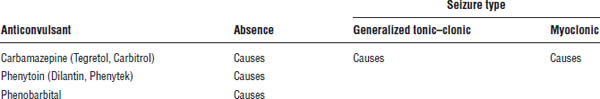

• Anticonvulsants that are used for treatment of a nonindicated seizure type (Table 28-1)

Criteria for Treating Epilepsy

Almost no child should be treated after one seizure. Adults who have structural brain damage, a first seizure that was very severe, or an occupation that places them at risk of injury should a second seizure occur may be treated following one seizure.

Principles in the treatment of epilepsy

■ Monotherapy (one agent): This form of treatment is always preferred.

Table 28-1. Seizures Caused by Anticonvulsants

■ Polytherapy (two agents): The addition of a second anticonvulsant should not be considered until the serum concentrations (where appropriate) and doses of the first anticonvulsant have been maximized. This approach is important in a patient who has developed side effects or has not responded to the first anticonvulsant. Generally, the second anticonvulsant should work through a different mechanism of action than the first. When the patient is at full doses of the second anticonvulsant, the dose of the first drug should be slowly reduced.

■ Polytherapy (three or more agents): Although rarely needed, add a third anticonvulsant if (1) a combination of two anticonvulsants is tolerated and significantly reduces seizure frequency or severity, but greater control might be achieved, or (2) doses of the two anticonvulsants have been maximized. Reassess response, and slowly discontinue unnecessary anticonvulsants as soon as possible.

Reasons for Treatment Failure

■ Incorrect diagnosis

■ Wrong anticonvulsant for seizure type

■ Inappropriate dose, route, or formulation

■ Failure to recognize altered pharmacokinetics or pharmacogenomics that require a dosage alteration

■ Poor patient adherence

■ Seizures that are refractory to therapy

Patient Counseling Information Applicable to All Anticonvulsants

■ It is important that you keep a diary of your seizures and keep regular appointments with your health care provider, so that he or she can determine whether your medication is working properly and whether you are experiencing unwanted side effects.

■ The full effects of this medication may not be seen for several weeks. Continue to take the medication unless directed otherwise by your health care provider.

■ Take with food or milk if upset stomach occurs.

■ Do not drink alcohol or take CNS depressants or illegal drugs with this medication.

■ If this medication causes blurred vision or drowsiness, do not drive or operate heavy machinery while taking this medication until you have become accustomed to its effects.

■ Consult with your health care provider if you anticipate pregnancy, become pregnant, or plan to breast-feed while taking this medication.

■ Some medications decrease the effectiveness of birth control pills. You should discuss this with your health care provider or pharmacist, who may recommend that you use a backup birth control method to prevent pregnancy.

■ If you are a woman capable of having children, you should take 1 mg of folic acid a day.

■ Do not stop taking this medication unless your health care provider advises you to do so; some medicines have to be stopped slowly. Let your health care provider or pharmacist know if you stop taking this medication.

■ Check with your pharmacist or health care provider before taking or starting any new medication (prescription, over-the-counter, or herbal product).

■ If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember. If it is almost time for the next dose, skip the missed dose and resume your regular schedule. Do not take extra or double doses. If you miss two or more doses, contact your health care provider for further instructions.

■ Contact your health care provider immediately if skin rash occurs.

Mechanisms of Action of Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsants work through a variety of mechanisms including the following:

■ Enhancing sodium channel inactivation

■ Reducing current through T-type calcium channels

■ Enhancing γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity

■ Enhancing antiglutamate activity

28-4. Medications Used to Treat Epilepsy

Carbamazepine

Carbamazepine is the most widely used anticonvulsant in adults and children. It is the drug of choice for complex partial seizures and is indicated for use in partial seizures with complex symptomatology (psychomotor, temporal lobe), generalized tonic–clonic seizures, and mixed seizure patterns. It is ineffective in absence seizures and febrile seizures.

Pharmacokinetics

■ Bioavailability: Good (75–85%); should be dispensed in moisture-proof containers because high humidity (as may occur in medicine cabinets) decreases bioavailability

■ Protein binding: 75–90% bound to α-1-acid glycoprotein; the 10,11-epoxide metabolite is 50% protein bound

■ Metabolism: Extensively hepatically metabolized to 10,11-epoxide, which is effective as an anticonvulsant and is capable of causing toxicity

■ Renal elimination: Low (1–3%)

■ Half-life: About one day if used as monotherapy and about 12 hours if given with more than one anticonvulsant

■ Reference range: 4–12 mg/L (monotherapy, 8–12 mg/L; polytherapy, 4–8 mg/L)

Other aspects

Carbamazepine is one of a few drugs that induce their own metabolism. Mean time to the onset of autoinduction is 21 days (range: 17–31 days).

Side effects

Upon initiation, side effects are nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, dizziness, and neutropenia. A dose-related, transient, and reversible rash may occur, but it rarely causes the drug to be discontinued.

With chronic therapy, the following side effects may occur:

■ Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) causing hyponatremia and water retention

■ Osteomalacia (treat with vitamin D if alkaline phosphatase is increased and 25-hydroxycholecalciferol if decreased)

■ Folate deficiency causing megaloblastic anemia

Some severe or life-threatening side effects are possible:

■ FDA boxed warning: Potentially fatal, severe dermatologic reactions (including Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis) may occur. Over 90% of patients who experience these reactions do so within the first few months of treatment. Patients of Asian descent are at higher risk and should be screened for the variant HLA-B*1502 allele (genetic marker) prior to initiating therapy.

■ FDA boxed warning: Aplastic anemia may occur. In such cases, discontinuation of carbamazepine is recommended if white blood count < 2,000–3,000 or neutrophils < 1,000–1,500.

■ FDA warning: Direct hepatotoxicity and multiorgan hypersensitivity reactions may occur and generally present within 1 month. Carbamazepine should be discontinued if liver function tests increase more than three times above normal. Fever, rash, or fatalities may occur even if carbamazepine is stopped.

■ FDA warning: Increased risk of suicidal behavior or ideation is possible. The FDA has analyzed suicidality reports from placebo-controlled studies involving 11 anticonvulsants (including carbamazepine) and found that patients receiving anticonvulsants had approximately twice the risk of suicidal behavior or ideation (0.43%) as patients receiving a placebo (0.22%).

■ Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome: This syndrome is characterized by fever (90–100%), rash (90%), hepatitis (50%), and other multiorgan abnormalities (50%). Although the mechanism is unknown, patients who have experienced this syndrome should not receive anticonvulsants with an aromatic structure (i.e., hydantoin, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, lamotrigine).

■ Teratogenic concerns: Carbamazepine is a pregnancy category D drug and has been associated with fetal carbamazepine syndrome (i.e., features include epicanthal folds, short nose, long philtrum, hypoplastic nails, microcephaly, developmental delay) and neural tube defects.

Drug–drug interactions

■ Carbamazepine is a cytochrome (CYP) 3A4, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 inducer.

■ Erythromycin, cimetidine, and lithium increase the serum concentration of carbamazepine and may enhance the effect to cause toxicity.

■ Phenobarbital, primidone, and phenytoin decrease the anticonvulsant effect of carbamazepine.

■ Carbamazepine may increase the serum concentration or effect of felbamate; felbamate will increase concentrations of the 10,11-epoxide metabolite carbamazepine and cause toxicity.

Commercially available formulations

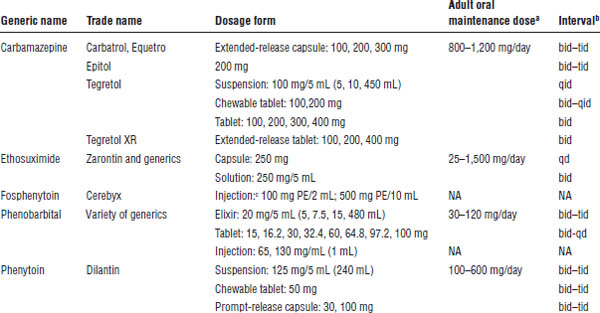

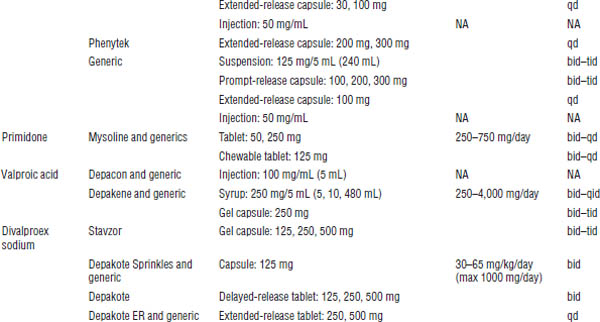

Table 28-2 shows the commercially available formulations.

Table 28-2. Dosage Forms, Normal Maintenance Doses, and Dosing Interval for Older Anticonvulsants

NA, not applicable; PE, phenytoin equivalent.

a. With the exception of the intravenous dosage forms, these anticonvulsants are begun at low doses and slowly titrated to a dose that will control the patient’s seizures.

b. Interval may either decrease or increase in the presence of medications that induce or inhibit metabolism, respectively.

c. 150 mg of fosphenytoin = 100 mg phenytoin.

Patient counseling

See general counseling information. In addition, counsel the patient as follows:

■ Shake suspension well.

■ Do not store in areas of high humidity (e.g., medicine cabinets).

■ Do not use with monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

Clobazam

Clobazam is a benzodiazepine indicated only for the adjunctive treatment of seizures associated with Lennox–Gaustaut syndrome in patients 2 years of age or older.

Pharmacokinetics

■ Bioavailability: 100% for oral tablets and solution

■ Protein binding: 80–90% for clobazam; 70% for active metabolite

■ Metabolism: Extensively hepatic (N-demethylation by CYP3A4 mostly, some CYP2C19 and CYP2B6); N-desmethylclobazam is the active metabolite and about 20% as potent as the parent compound.

■ Renal elimination: 82%

■ Half-life: 36–42 hours (71–82 hours for active metabolite)

Side effects

Common side effects include constipation, somnolence or sedation, pyrexia, lethargy, and drooling.

Severe or life-threatening effects are also possible:

■ Serious dermatological reactions: Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported in children and adults during the postmarketing period. Patients should be closely monitored for signs and symptoms, especially in the first 8 weeks of treatment. Discontinuation of clobazam should be considered at the first sign of rash and alternative therapy reviewed.

■ Suicidal behavior and ideation: Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior. Patients should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Drug–drug interactions

Because of the metabolism of clobazam, lower doses of medications metabolized by CYP2D6 may be needed when used concomitantly with clobazam. The clobazam dose may need to be adjusted with strong or moderate CYP2C19 inhibitors. Alcohol increases levels of clobazam by approximately 50%; therefore, patients and caregivers should be cautioned against simultaneous use.

Commercially available formulations

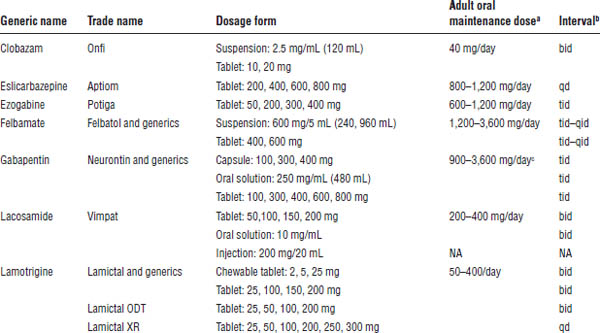

See Table 28-3 for commercially available formulations.

Eslicarbazepine

Eslicarbazepine is the pro-drug for the major active metabolite of oxcarbazepine. It is indicated for use as adjunctive treatment of partial seizures.

Pharmacokinetics

■ Bioavailability: Peak concentrations are obtained 1–4 hours post dose.

■ Protein binding: Low (< 40%)

■ Metabolism: Hydrolytic first-pass metabolism converts eslicarbazepine acetate to eslicarbazepine; minor active metabolites include (R)-licarbazepine and oxcarbazepine.

■ Renal elimination: 100%

■ Half-life: 13–20 hours; steady-state concentrations are attained after 4–5 days of once-daily dosing.

Side effects

Common side effects include dizziness, somnolence, nausea, headache, diplopia, vomiting, fatigue, vertigo, ataxia, blurred vision, and tremor.

Severe or life-threatening effects are also possible:

■ Suicidal behavior and ideation: AEDs may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior. Patients should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

■ Serious dermatologic reactions: Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported with eslicarbazepine, oxcarbazepine, and carbamazepine use. Consider discontinuation of drug at the first sign of rash and alternative therapy thereafter.

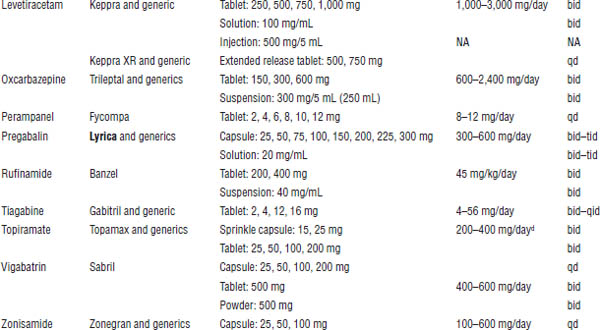

Table 28-3. Dosage Forms, Normal Maintenance Doses, and Dosing Intervals for the Newer Anticonvulsants

NA, not applicable.

Boldface indicates one of top 100 drugs for 2012 by units sold at retail outlets, www.drugs.com/stats/top100/2012/units.

a. With the exception of gabapentin, these anticonvulsants are begun at low doses and slowly titrated over weeks to a dose that will control the patient’s seizures.

b. Interval may either decrease or increase in the presence of medications that induce or inhibit metabolism, respectively.

c. Much larger doses have been given.

d. The recommended maintenance doses for initial monotherapy and adjunctive therapy are 400 mg/day and 200–400 mg/day, respectively. Doses > 400 mg are no more effective than doses ≤ 400 mg.

■ Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: This has been reported in patients taking eslicarbazepine. Monitor for hypersensitivity, and discontinue use if another cause cannot be established.

■ Anaphylactic reactions and angioedema: Rare cases of anaphylaxis and angioedema have been reported in patients taking this medication. Monitor for breathing difficulties or swelling, and discontinue if another cause cannot be established.

■ Hyponatremia: Significant hyponatremia (< 125 mEq/L) may occur, and thus sodium levels in patients at risk for or patients experiencing hyponatremia symptoms should be monitored.

■ Drug-induced liver injury: Eslicarbazepine should be discontinued in patients with jaundice or laboratory evidence of significant liver injury.

Drug–drug interactions

Several AEDs, including carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone, can induce enzymes that metabolize eslicarbazepine and can cause decreased plasma concentrations. In addition, eslicarbazepine may decrease the effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives. Additional or alternative nonhormonal birth control should be advised. Do not use eslicarbazepine with oxcarbazepine.

Commercially available formulations

See Table 28-3 for commercially available formulations.

Ethosuximide

Indications are absence and myoclonic seizures.

Pharmacokinetics

■ Bioavailability: Good

■ Protein binding: Very low (< 10%)

■ Metabolism: 80% hepatically metabolized to three inactive metabolites

■ Renal elimination: 50% as metabolites; 10–20% as unchanged drug

■ Half-life: 30–60 hours

■ Reference range: 40–100 mg/L

Side effects

Upon initiation, side effects are nausea, vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, lethargy, headache, rashes (including Stevens–Johnson syndrome), and urticaria.

With chronic therapy, anorexia and weight loss, as well as gum hypertrophy, could occur.

■ Suicidal behavior and ideation: AEDs may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior. Patients should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Drug–drug interactions

■ Ethosuximide is a CYP3A3/4 substrate.

■ Phenytoin, carbamazepine, primidone, and phenobarbital may increase the clearance of ethosuximide.

■ Isoniazid may inhibit metabolism and increase ethosuximide serum concentrations.

Commercially available formulations

See Table 28-2 for commercially available formulations.

Ezogabine

Ezogabine is a potassium channel opener indicated for the adjunctive treatment of partial seizures in adult patients and was approved by the FDA in 2011. It should be used only in those patients with epilepsy that cannot be controlled by other agents, and the benefits versus the risks of retinal abnormalities and decline in visual acuity should be considered.

Pharmacokinetics

■ Bioavailability: Approximately 60%

■ Protein binding: Approximately 80%

■ Metabolism: Hepatic via extensive glucuronidation and acetylation; the N-acetyl metabolite (NAMR) is the main active metabolite with weaker antiepileptic activity.

■ Renal elimination: 85% renal elimination (36% unchanged drug, remainder as metabolites)

■ Half-life: 7–11 hours for the drug and active metabolite

Side effects

The most common adverse reactions reported are dizziness, somnolence, fatigue, confusion, vertigo, tremor, abnormal coordination, diplopia, attention disturbance, memory impairment, asthenia, blurred vision, gait disturbance, aphasia, dysarthria, and balance disorders.

Severe or life-threatening effects are also possible:

■ FDA boxed warning: Ezogabine may cause retinal abnormalities leading to damage to the photoreceptors and vision loss. The rate of progression and reversibility is unknown. Visual acuity and dilated fundus photography is recommended at baseline and every 6 months for patients taking ezogabine. If any abnormalities are detected, the medication should be discontinued unless no other treatment options exist.

■ Urinary retention: In placebo-controlled trials, an increased risk of urinary retention occurred while taking ezogabine. Urologic symptoms should be monitored, especially for patients with other risk factors or on concomitant medications that may affect voiding (i.e., anticholinergics).

■ Skin discoloration: Ezogabine may cause blue, gray-blue, or brown skin discoloration that is found predominantly on or around the lips or in the nail beds. Widespread involvement to the face and legs has also been reported. This was generally reported after 2 or more years of therapy.

■ QT interval effect: There was a mean QT prolongation in healthy volunteers of 7.7 msec that occurred within 3 hours. The QT interval should be monitored in patients using ezogabine concomitantly with medicines known to increase QT interval and in patients with known prolonged QT interval, congestive heart failure, ventricular hypertrophy, hypokalemia, or hypomagnesemia.

■ Suicidal behavior and ideation: AEDs, including ezogabine, may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behavior. Patients should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts or behavior, or any unusual changes in mood or behavior.

Drug–drug interactions

Concomitant administration of phenytoin or carbamazepine may reduce ezogabine plasma levels; therefore, an increased dose of ezogabine should be considered when adding either of these two drugs. The active metabolite of ezogabine may inhibit renal clearance of digoxin; thus, monitoring digoxin levels is recommended.

Commercially available formulations

See Table 28-3 for commercially available formulations.

Felbamate

Felbamate should be used only as adjunctive therapy in severe refractory partial seizures, with or without secondary generalization, in patients older than 14 years of age and in partial or generalized seizures associated with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. It should be used only in patients with epilepsy so severe that the risk of aplastic anemia, liver failure, or both is deemed acceptable given the potential benefits of its use.

Pharmacokinetics

■ Bioavailability: Complete (> 90%)

■ Protein binding: Low (20–25%)

■ Metabolism: Hepatic via hydroxylation and conjugation

■ Renal elimination: 40–50% excreted unchanged and 40% as inactive metabolites in urine

■ Half-life: 20–30 hours; shorter (i.e., 14 hours) with concomitant enzyme-inducing drugs; prolonged (by 9–15 hours) in renal dysfunction

■ Reference range: Although some have proposed a therapeutic range of 30–100 mg/L, routine monitoring of serum drug concentrations is not advocated; hence, the dose should be titrated to clinical response.

Side effects

Upon initiation, nausea and vomiting, anorexia, headache, insomnia, and dizziness may occur.

With chronic therapy, weight loss significant enough to warrant discontinuing the medication is possible.

Severe or life-threatening side effects are possible:

■ FDA boxed warning: Direct hepatotoxicity may occur at any time; however, the earliest onset of severe liver dysfunction occurred 3 weeks after starting felbamate. It is not known if dose, duration, or use of concomitant medications affects the risk. Liver enzyme and bilirubin tests should be obtained before initiation and periodically after starting felbamate, and the drug should be immediately withdrawn if liver function tests become elevated. Most cases require liver transplantation.

■ FDA boxed warning: The risk of aplastic anemia may be 100 times greater than in the general population and can develop at any point without warning. Complete blood count with differential and platelet count should be taken before, during, and for a significant time after discontinuing felbamate. Felbamate should be immediately withdrawn if bone marrow suppression occurs.

■ FDA warning: Increased risk of suicidal behavior or ideation may occur. The FDA has analyzed suicidality reports from placebo-controlled studies involving 11 anticonvulsants (including felbamate) and found that patients receiving anticonvulsants had approximately twice the risk of suicidal behavior or ideation (0.43%) as patients receiving a placebo (0.22%).

Drug–drug interactions

■ Felbamate induces CYP3A4.

■ Felbamate inhibits CYP2C19, epoxide hydroxylase, and β-oxidation.

■ Carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and phenytoin decrease the anticonvulsant effect of felbamate.

■ Phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproic acid increase the anticonvulsant effect of felbamate.

■ Felbamate decreases carbamazepine concentrations but increases the concentration of carbamazepine 10,11-epoxide (active metabolite), which may result in toxicity.

■ Felbamate increases the serum concentrations of phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproic acid. When felbamate is begun, a 20% reduction in phenytoin dose resulted in phenytoin concentrations comparable to those prior to initiation of felbamate.

Commercially available formulations

See Table 28-3 for commercially available formulations.

Patient counseling

See general counseling information. An information consent form is included as part of the package insert and is available from the local representative or by calling 800-526-3840. The patient or legal guardian should sign this form before receiving the medication.

Fosphenytoin

Fosphenytoin is indicated for short-term parenteral administration in treating generalized convulsive status epilepticus. The safety and effectiveness of more than 5 days’ use has not been systematically evaluated.

Pharmacokinetics

■ Bioavailability: Time for complete conversion to phenytoin is 15 minutes and 30 minutes after intravenous (IV) and intramuscular (IM) administration, respectively.

■ Protein binding: Protein binding is high (95–99% primarily to albumin).

■ Metabolism: Each millimole of fosphenytoin is metabolized to 1 millimole of phenytoin, phosphate, and formaldehyde. Formaldehyde is then converted to formate, which is metabolized by a folate-dependent mechanism. Conversion increases the dose and infusion rate, most likely because of a decrease in fosphenytoin protein binding.

■ Renal elimination: None

■ Half-life: See the later discussion of phenytoin for the half-life of the active drug.

■ Reference range: 10–20 mg/L (phenytoin)

Side effects

Upon initiation, side effects include hypotension (with rapid IV administration), vasodilation, tachycardia, and bradycardia; burning, pruritus, tingling, and paresthesia (predominately in the groin area); and rash and exfoliative dermatitis. Prolonged use will result in the same side effects as those seen with phenytoin (see side effects for phenytoin).

■ FDA warning: The FDA is investigating the possibility of an increased risk of serious skin reactions (e.g., Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis) in patients given phenytoin who have the human leukocyte antigen allele HLA-B*1502. This allele occurs almost exclusively in individuals with ancestry across broad areas of Asia, including Han Chinese, Filipinos, Malaysians, South Asian Indians, and Thais. Until the FDA evaluation is finalized, fosphenytoin should be avoided in patients who test positive for HLA-B*1502.

Drug–drug interactions

See the later discussion of phenytoin for drug–drug interactions.

Commercially available formulations

See Table 28-2 for commercially available formulations.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is indicated as adjunctive therapy for partial seizures with and without secondary generalization in those older than 12 years of age. It is also indicated as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of partial seizures in patients 3–12 years of age.

Pharmacokinetics

■ Bioavailability: Poor (60% with decreasing absorption as age decreases)

■ Protein binding: Very low (< 3%)

■ Metabolism: None

■ Renal elimination: 100%

■ Half-life: Short (< 12 hours); increases with decreased renal function (anuric patients: 132 hours; decreased during hemodialysis to about 4 hours)

■ Reference range: Routine monitoring of serum concentrations not required; minimum effective concentration thought to be 2 mg/L

Side effects

Upon initiation, somnolence, dizziness, ataxia, fatigue, and nervousness may occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree