Seizure Disorders

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

• INTRODUCTION

According to most sources, epilepsy is a condition of recurrent, unprovoked seizures caused by an inherent brain abnormality. Seizures occur when the normal chemical and electrical activity of the brain is disturbed, which leads to changes in behavior, function, or attention. These manifestations can include visible abnormal motor activity, loss of consciousness, and/or memory loss, as well as abnormal sensory, psychic, or autonomic symptoms. Focal or generalized, abnormal increased muscular activity due to a seizure is called convulsion. Because many types of epilepsy do not involve convulsions, the term is less often used in the context of epilepsy or seizure disorders.

While all drugs currently used to treat epilepsy are really antiseizure medications, which suppress abnormal electrical and chemical activity in the brain, they are usually called antiepilepsy drugs (AEDs). This is primarily because seizure activity that either consists of a single event and/or has an identifiable reversible cause does not warrant chronic drug therapy.

The pharmacist’s role in epilepsy is primarily monitoring the patient’s response to drug therapy, preventing adverse effects and assisting with optimal medication adherence.

• ETIOLOGY

Seizures can be triggered by numerous temporary and potentially correctable conditions such as high fever, head trauma, electrolyte disturbances, medications, alcohol withdrawal, vascular malformations, tumor, infection, or stroke. These seizures are considered to be provoked and will not recur once the offending cause is corrected. If seizures occur repeatedly and chronically, and it is not provoked by an identifiable cause, the condition is called epilepsy. Over 3 million people in the United States have epilepsy (0.5% to 1% of the population).

• DIAGNOSIS

While the cause of a seizure disorder and the diagnosis of epilepsy is done primarily by medical personnel and physician specialists, pharmacists need to know the most common causes and how the diagnosis is made. When evaluating a patient for the first time, it is important to obtain a complete and detailed patient history. Ideally, this would include a detailed description from those who have witnessed the patient’s seizures. A complete physical examination, including a thorough neurological examination must be performed. In addition to a careful history and examination, selective laboratory screening along with other tests should be performed to look for temporary or reversible causes of the seizure. Therefore, electrolytes, glucose, calcium, magnesium, CBC, renal function, liver function, and toxicology screenings should be determined. A lumbar puncture or spinal tap is performed if the clinical presentation suggests the following: an acute infection that involves the CNS, a history of cancer that is known to metastasize in the brain, or a subarachnoid hemorrhage or stroke. Patients on potentially seizure-inducing medication, e.g., theophylline, should have serum levels measured.

The electroencephalogram (EEG) is used to measure the electrical activity in the brain. If abnormal, it can be helpful in the diagnosis of an epileptic seizure. This test may be able to pinpoint the location in the brain where the seizures start and suggest whether a patient has generalized or partial seizures. Often after a patient’s first seizure, the EEG may appear normal. The use of sleep deprivation, hyperventilation, and intermittent photic stimulation is used to increase the brain activity in an attempt to find an abnormal focus via the EEG. However, a normal EEG does not rule out epilepsy after having a seizure.

Finally, if a cause of the patient’s seizure is not discovered with the above workup, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or in an emergency computerized tomography (CT scan) of the brain should be performed to rule out changes due to the seizure (which may persist for days or weeks), and to identify structural causes of the seizures (infarct or hemorrhage due to a stroke, or mass occupying lesion such as a brain tumor).

• CLASSIFICATION

While there have been several different systems to classify seizures, the most commonly used system is the simplified international classification of seizures. The optimal therapeutic plan varies by the specific type of seizure. Each patient’s treatment plan should be individualized to the extent possible, based on their specific type of seizure. There are three major categories of seizures: partial seizures (sometimes called focal seizures), generalized seizures, and unclassifiable seizures. Partial seizures start in a focal region of the brain (i.e., one side or hemisphere). They can be either simple or complex. Simple partial seizures do not cause loss of consciousness or memory, but may involve focal motor activity (jerking of a single limb) and/or sensory abnormalities (visual, auditory, or olfactory). They may also cause abnormal thoughts or perceptions, or even autonomic symptoms such as nausea, flushing, or tingling. Complex partial seizures do cause loss of consciousness or memory and have somewhat different presentations. The manifestations are usually repeated motor activities like lip smacking, chewing, swallowing, hand rubbing, walking about without purpose, and/or repeated verbal statements that may be nonsensical word strings. These are termed automatisms. Complex partial seizures were previously called called temporal lobe or psychomotor seizures and patients may still use the terms. Both of these types of partial seizures will remain focal throughout their duration unless they become generalized. However, either type of partial seizure can become secondarily generalized to the entire brain, leading to generalized tonic-clonic seizures, which are referred to as complex partial seizures with secondary generalization. Complex partial seizures comprise about 40% of all adult seizures and simple partial seizures comprise about another 20%.

Primary generalized seizures include absence (previously known as petit mal), tonic-clonic (previously known as grand mal), myoclonic, atonic, and clonic seizures. They originate and spread throughout both hemispheres of the brain. Primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures, probably the most familiar to the lay public, comprise about 20% of all adult seizures. They begin with a sudden loss of consciousness and frequently with eyes rolling upward and sometimes with a shout or a cry, due to contraction of respiratory muscles against the closed throat. Then the tonic phase begins, consisting of involuntary strong sustained contraction of the muscles of the extremities, neck, and trunk usually described as stiffening in extension. Patients’ facial expressions may appear distorted. This is followed by the clonic phase, which consists of rhythmic types of jerking movements of the extremities. Urinary and/or fecal incontinence may accompany these general tonic-clonic seizures. Also, these are usually followed by upto several hours of drowsiness, known as the post-ictal phase. Absence seizures, a less dramatic form of generalized seizures, consist of staring spells. However, they may also include a fluttering of the eyes and/or a nodding of the head. Sometimes, they appear similar to complex partial seizures and the differentiation can require an EEG tracing. These seizures comprise approximately 10% of adult seizures, but a greater percentage in pediatrics. The remainder of generalized seizure types comprises the last 10% of adult seizures.

In addition to this classification of seizure types, there are also various uncommon epilepsy syndromes, e.g., febrile seizures, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

• INITIAL VISIT

Once a diagnosis of epilepsy has been confirmed, goals of therapy are to minimize seizure activity and severity, avoid treatment-related side effects, and maintain or improve quality of life. The type of seizure a patient has will determine which medications will be prescribed. Other factors that should be considered when choosing a medication regimen include potential drug-drug, drug-nutrient, and drug-disease interactions, age, gender, individualized goals of therapy, medical history, potential adverse effects, and psychological history. Women represent a special group of patients due to the possibility of anticonvulsants interfering with oral contraceptive efficacy, complicating breast feeding, and potentially causing birth defects. For readers interested in these specific issues, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Epilepsy Society have issued three sets of practice guidelines, in 2009, dealing with best practices in women with epilepsy. Roughly two-thirds of patients will respond to drug therapy alone. An additional role for the pharmacist can be to help identify those patients whose seizures are truly resistant to medication and not caused by insufficient dosing or nonadherence. About one-third of patients diagnosed with epilepsy turn out to be resistant to drug therapy and require specialist management.

• FOLLOW-UP VISIT (See Table 23.1)

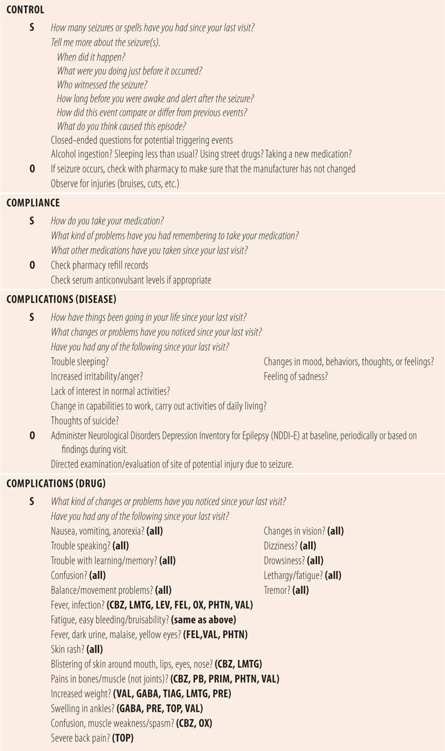

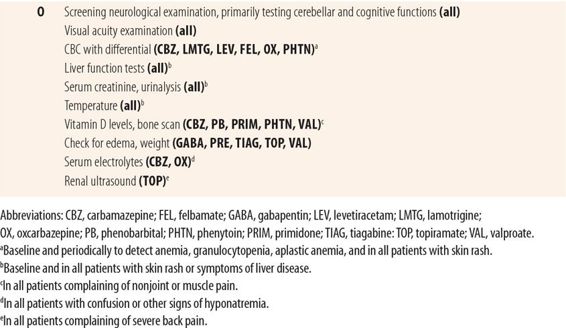

| TABLE 23.1 | Follow-Up Visit Seizure Disorder |

Control

The extent of the patient’s seizure activities since their last visit is the primary measurement of disease control. Ask patients directly using an open-ended question such as, “How many seizures or spells have you had since your last visit?” If the patient did have one or more seizures, there is a need to ask for more details about each episode. Was there a witness who can tell you the details of the seizure? When did it happen? How long did it last? What were they doing before it occurred? Patients may not remember what happened during their episode so it is important to have a witness provide details, wherever possible. In addition, patients should be queried regarding any of the following that may have occurred around or before the time of the seizure: sleep deprivation, ethanol binge, illicit drug use, or a new medication that may lower seizure threshold such as phenothiazines, theophylline, or bupropion. In addition, the pharmacy should be contacted to make sure that the manufacturer of the anticonvulsant has not changed, which could lead to altered serum levels.

One of the problems about relying on subjective information is that the actual numbers of seizures are generally underreported due to lack of patient awareness and/or willful misrepresentation to avoid losing driving privileges. Most states require 3 to 12 months of seizure free status verified in writing by their physician to obtain or renew a driver’s license. Sometimes, the patient can injure themselves during a seizure. Observation for potential evidence of trauma such as a cut lip, swollen body part, bruising, limping, or restricted range of movement may require more in-depth questioning and examination to determine if they were caused by a seizure.

Compliance

Adherence to the medication regimen is essential to disease control. Open-ended probes as seen in Table 23.1 can start the discussion. If suboptimal adherence is suspected as a cause for inadequate seizure control, pharmacy refill records can be checked and reliable serum drug levels can be measured. Suboptimal adherence is common among patients with epilepsy because of potentially complex regimens, frequent annoying adverse effects, and the nature of the disease. In particular, patients with well-controlled epilepsy are known to take “medication holidays” to demonstrate they are not controlled by medication or that they do not really need it. These holidays may start out as just a dose or two, but may expand to longer periods. This is complicated by the fact that in many seizure disorders, there are periods where no electrical discharges that cause seizures are generated. If the holiday coincides with a period of seizure inactivity, then the holiday can last for weeks or months until a seizure recurs.

Complications of the Disease

In addition to seizures, the major complications are psychosocial in nature. Many patients struggle with a loss of independence and can become depressed. Some epileptic patients are unemployed regardless of their college education. Due to increased risk from injury, many patients have activity restrictions, which can make them feel isolated and alone. Many patients develop poor self-esteem when they have problems getting insurance or keeping a suitable job. Family and friends can also struggle to adapt to a person with epilepsy. For providers, patients, and families who want to gain insight into these issues, the Brainstorm series of books by Steven Schachter offer insight into the feelings of patients with epilepsy and those of their family and friends.

Depression is a common complication of epilepsy. Over half of all patients with uncontrolled epilepsy are depressed and the risk of suicide is several times higher than in patients without seizures. In 2008, the FDA issued “black box warnings” based on their analysis of clinical trials of a higher suicide rate in patients on all anticonvulsant medications compared to placebo. The mechanism relating epilepsy and anticonvulsants to depression and suicide is unknown. It may be epilepsy, medications, or a combination of both. Regardless of the cause, providers must be diligent in screening for depression at each visit. Asking general questions about their life, work, or family as appropriate can provide clues to negative changes in their life. Observing for changes in mood and affect plus asking direct open-ended questions regarding symptoms of depression or thoughts of suicide should be done at each visit. A more objective measure specifically designed for patients with epilepsy, the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E), should be administered at baseline during the initial visit and thereafter, either periodically or as indicated by findings during subsequent visits. Patients, suspected of having depression, need to be referred to a qualified mental health provider.

Complications of Drugs

Most antiepileptic drugs are metabolized in the liver and many are CYP 450 inducers or inhibitors. Given the nature and properties of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), there is a high risk for significant drug-drug interactions involving not only other AEDs, but many medications for comorbid conditions as well. The pharmacist’s role is to analyze all the patient’s medications, even those for comorbid conditions for potential significant interactions. In addition, the pharmacist should educate the patient to ask about potential interactions before starting any other medications. This is all in addition to routine education about their disease and proper use of their individual medications.

Many AEDs share adverse effects as a class. Most cause some incidence of gastric upset, anorexia, nausea, or vomiting. These can be minimized by starting with a low dose and titrating upward slowly. All can cause disruptions and adverse effects related to the central nervous system (CNS) including visual disturbances, drowsiness, fatigue, lethargy, trouble with memory and learning, confusion, or tremor. Probing for these symptoms should be done at each visit along with administration of the Folstein mini-mental status examination (MMSE) as indicated. Seizure medications can impair cerebellar function (movement and balance). This effect is evaluated with the portion of a neurological examination that tests for cerebellar function (gait, balance, and nystagmus). These CNS signs and symptoms are more frequent when initiating therapy and when increasing dosages or adding additional anticonvulsants or other medication with CNS depressant properties. In addition, cerebellar or cognitive impairment may be an indication of excess medication serum levels. Fortunately, most decrease with time. Problems with cognition can be common and very troublesome, but patient perceptions of cognition problems can be based primarily on mood rather than actual performance and the persistence of complaints should prompt a more thorough investigation for signs and symptoms of depression.

Many AEDs have been implicated in drug hypersensitivity syndrome, also known as anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome, or DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms). It occurs more frequently with the older AEDs. It has been estimated to occur in one of every 10,000 patients. Since it is associated with an 8% mortality rate, it is important to ask during every visit about skin rashes. Drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DHS) includes not only a widespread maculopapular-papular rash on the trunk, arms, and legs but systemic signs as well. DHS usually presents with a high fever followed by the rash. Systemic effects include eosinophilia in 50% to 90% of the cases. Thirty percent have abnormal lymphocytosis and 20% have lymphadenopathy. Eventually, the liver and/or kidneys become involved as indicated by elevated AST or ALT levels and/or proteinuria, or elevated serum creatinine, respectively.

Individual AEDs are associated with a variety of adverse drugs reactions including granulocytopenia, aplastic anemia, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug-induced hepatitis, and hyperammonemia. Therefore, it is important to monitor specific medications via liver function tests, complete blood counts, basic metabolic panels, and ammonia levels to look for possible adverse effects of drug therapy (Table 23.1).

• SUMMARY

The pharmacist’s role in epilepsy is primarily monitoring and adjusting drug therapy to prevent seizures, minimize adverse effects, and optimize quality of life. Using careful history taking and focused physical assessment, the pharmacist applies their knowledge of the presentation of various types of seizures, the unwanted effects for each anticonvulsant, and their medication adherence support skills to assist the patient in optimizing therapy.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Elger CE, Schmidt D. Modern management of epilepsy: a practical approach. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:501-539.

2. French JA, Pedley TA. Initial management of epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:166-176.

3. Schachter SC. Seizure disorders. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:343-351.

4. Leeman BA, Cole AJ. Advancements in the treatment of epilepsy. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:503-523.

5. Landmark CJ, Johannssen SI. Pharmacological management of epilepsy. Drugs. 2008;68:1925-1939.

6. Raspall-Chaure M, Neville BG, Scott RC. The medical management of epilepsy in children. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:57-69.

7. Stein MA, Kanner AM. Management of newly diagnosed epilepsy: a practical guide to monotherapy. Drugs. 2009;69:199-222.

8. Stephen LJ, Brodie MJ. Selection of antiepileptic drugs in adults. Neurol Clin. 2009;27:967-992.

9. Schacter SC. Brainstorms: Epilepsy in Our Words. Personal Accounts of Living with Seizures. New York: Raven Press; 1993.

10. Schacter SC. The Brainstorms Companion: Epilepsy in Our View. New York: Raven Press; 1995.

11. Saiz-Diaz RA, Sancho J, Serratosa J. Antiepileptic drug interactions. Neurologist. 2008;14:S55-S65.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree