Summary by Iliya P. Amaza, MD, MPH, Aleksandra Zgierska, MD, PhD, and Michael F. Fleming, MD, MPH

18

Based on “Principles of Addiction Medicine” Chapter by Aleksandra Zgierska, MD, PhD, and Michael F. Fleming, MD, MPH

Unhealthy substance use (“misuse”) presents an important public health problem. An estimated 30% of the US population is affected by alcohol misuse, and up to a fifth of adult primary care patients meet criteria for alcohol use disorders (AUDs). Tobacco and alcohol misuse are the estimated first and third leading causes of preventable deaths, and prescription drug abuse has reached the level of an epidemic in the United States. Health conditions frequently associated with substance misuse include memory loss, hypertension, liver disease, or even death, among others. Screening and Brief Intervention (SBI), and—when appropriate—a Referral to a specialty, addiction Treatment program (SBIRT) is a promising and now well-established approach for decreasing negative outcomes associated with substance misuse.

Brief intervention (BI) is a time-limited, client-centered counseling session designed to reduce substance use. Each session lasts for about 5 to 20 minutes. Multiple BI sessions seem to be more effective than a single contact. BI’s unique approach is based on a harm reduction paradigm, which contrasts with an abstinence model used in traditional treatments. The BI’s treatment goal is to reduce the risk of negative, substance use–related consequences. SBI is one of the most popular clinical “tools” utilized by primary care clinicians. The principles of SBI approach can essentially be applied to any medical condition.

NATIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF SCREENING AND TREATMENT FOR UNHEALTHY SUBSTANCE USE IN MEDICAL CARE SETTINGS

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends routine SBI to reduce alcohol misuse by adults, including pregnant women in primary care settings; it also recommends that clinicians provide tobacco cessation interventions for all tobacco users, including children and adolescents. The USPSTF concludes, though, that the evidence is insufficient to recommend routine SBI for alcohol misuse among children and adolescents and for illicit and prescription-based drug misuse. However, many professional medical organizations as well as research institutes, such as the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), endorse recommendations to implement routine SBI for alcohol, tobacco, and drug misuse among adults and adolescents in general and mental health care settings.

SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION: CLINICAL GUIDELINES

Clinical Approach to the SBI Services in Primary Care Settings

The SBI process often follows the 5-As approach:

- 1-Ask: screen and assess the risk (severity) level. Intervention is then tailored to the screening results and determined risk (severity) level.

- 2-Advise: provide direct personal advice about substance use. The patient needs to hear that a change in behavior is recommended based on medical concerns and to learn about the effects of their personal substance use on health. Facts should be presented in an objective nonjudgmental way, using unambiguous and personalized language.

- 3-Assess: evaluate the patient’s willingness (“readiness”) to reduce or quit the unhealthy behavior. If the patient is unwilling, restate the health concerns, reaffirm your willingness to help when the patient is ready, and encourage the patient to reflect about perceived “benefits” of continued use versus decreasing or stopping use, and explore barriers to change.

- 4-Assist: help the interested patient develop the treatment plan following the patient’s personal goals. Use behavior change techniques, such as motivational interviewing, to aid the patient in achieving agreed-upon goals and acquiring the appropriate skills, confidence, and social/environmental support. Other issues to consider include the following:

- Medical treatment for addiction, such as detoxification or pharmacotherapy

- Additional assessment and therapy for potential comorbid physical or mental health problems

- Safe sex counseling, and testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in sexually active patients

- HIV and hepatitis B/C testing among injection drug users

- Medical treatment for addiction, such as detoxification or pharmacotherapy

- 5-Arrange: schedule a follow-up appointment and consider specialty referrals. Provide educational materials and ongoing assistance. Encourage patient to see an addiction specialist, if needed, and engage in mutual self-help groups, such as Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous or SMART Recovery.

SBI for Unhealthy Substance Use (Alcohol, Drugs, Tobacco): Guidelines

Unhealthy Substance Use Screening

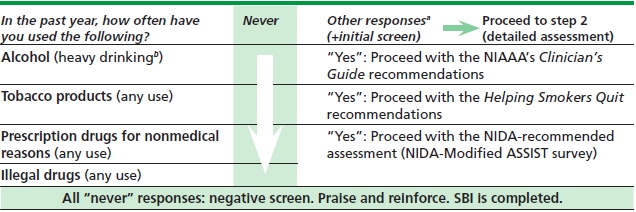

The NIDA-recommended approach is one of several tools available for the routine implementation of SBI for unhealthy substance use in clinical practice.

Following the NIDA algorithm, patients are first screened using the Quick Screen consisting of a single question about past-year substance use (Table 18-1). A negative Quick Screen (“Never” response to alcohol, tobacco, or drugs) completes the evaluation. Patients with a negative screen should be praised and encouraged to continue healthy lifestyle, then rescreened at least annually. Those answering “yes” to this initial question (positive Quick Screen) should receive further assessment. The NIDA guide provides links to alcohol, tobacco, or drug-specific SBI resources (see Table 18-1). Following the assessment, a personalized brief advice or brief intervention, along with arrangements for follow-up, completes the SBI process.

TABLE 18-1. “ASK”: SINGLE-QUESTION INITIAL SCREEN FOR SUBSTANCE MISUSE IN ADULTS (NIDA QUICK SCREEN)

aPossible responses: “once or twice,” “monthly,” “weekly,” or “daily or almost daily.”

bHeavy drinking: 5 or more (for men) or 4 or more (for women) drinks in a day.

Adapted from Resource Guide: Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. NIDA. Revised: March 2012.

Alcohol SBI in Adults

Alcohol Screening and Severity Assessment in Adults

The NIAAA’s Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide provides detailed step-by-step guidance to alcohol SBI in primary care and mental health settings.

- Consider prescreening by asking about any alcohol use: “Do you sometimes drink beer, wine, or other alcoholic beverages?” Negative answer completes the SBI process.

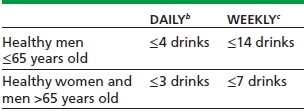

- Screen using a single question about heavy drinking: “How many times in the past year have you had 5 (4) or more drinks in a day?” (Table 18-2). Charts defining “standard” drink are very useful.

- If negative screen, praise the patient. Clinicians can recommend individually tailored lower “drinking limits” or even abstinence as based on the patient’s unique clinical situation, for example, due to drug interactions, comorbid mental health problems, or pregnancy.

- If positive screen, determine the patient’s usual weekly alcohol consumption (“On average, how many days a week do you have an alcoholic drink?” AND “On a typical drinking day, how many drinks do you have?”) (see Table 18-2).

- Assess the severity or scope of potential problems: The NIAAA’s Clinician’s Guide tool or the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) can be used to distinguish between “at-risk drinking” and AUDs (abuse or dependence). Severity assessment help guide clinical approach (brief advice or intervention).

TABLE 18-2. MAXIMUM (LOW-RISK) DRINKING LIMITS FOR ADULTSa

aOne standard drink is equivalent to 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof spirits.

bExceeded daily limit: heavy drinking.

cExceeded daily or weekly limit: at-risk drinking.

Adapted from Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. NIAAA. Updated 2005 Edition.

Alcohol Brief Intervention in Adults

With the patient’s agreement, provide, in an empathic and nonconfrontational manner, an objective summary of the patient’s level of drinking, related consequences and risks as well as clear, specific, and personalized behavior change advice.

Abstinence can produce better treatment outcomes than drinking reduction in people with AUDs, especially dependence. Abstinence may also be recommended as a primary treatment goal for patients without AUDs but with specific comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions. However, for many people who should, but are not willing to abstain, drinking reduction may be more acceptable. Even modest reduction in drinking can result in decreased alcohol-related harms.

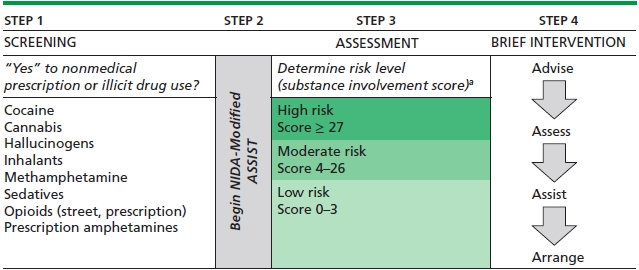

Drug SBI: Assessment of Severity

Based on the NIDA guidelines, those with a positive screen for drugs (“yes” to any use of illicit drugs and misuse of prescription-based drugs) should receive further assessment using the NIDA-Modified ASSIST (NM-ASSIST) questionnaire to determine the “risk level” (Table 18-3). Depending on the “risk level,” the patient should then receive either a brief advice or full BI and, if needed, a referral to treatment to complete the process.

TABLE 18-3. SBI FOR DRUG MISUSE IN ADULTS

aIf use of more than one substance is reported, repeat the NM-ASSIST for each drug and score each substance endorsed, then focus intervention on the substance with the highest Substance Involvement score or per patient’s preference.

Adapted from Resource Guide: Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. NIDA. Revised: March 2012.

SBI for Youth

Substance Use in Youth: General Considerations

One in three children has had an alcoholic beverage by the end of 8th grade, with half of them reporting getting drunk. Underage drinking is closely associated with serious consequences such as death, injuries, and motor vehicle crashes. Factors known to influence substance use among youth include, among others, the pattern of substance use in the community, permissive parental attitudes, and having friends or family members using alcohol, tobacco, or drugs.

Although the USPSTF found existing evidence insufficient to recommend for or against routine alcohol and drug SBI in youth, research lends support for effectiveness of SBI for adolescents, and professional organizations such as NIAAA, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend routine screening of all children and youth between ages 9 and 18 years at least annually. Those with mental health problems known to co-occur with substance abuse (e.g., depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity, conduct, schizophrenia, or bulimia disorders), with physical health conditions that might be explained by substance use, who engage in high-risk behaviors (e.g., history of STDs or pregnancy) or show substantial negative behavioral changes, should be screened during each clinic visit.

Confidentiality and Parental Involvement

When discussing substance use with minors, issues surrounding patient confidentiality and parental or guardian involvement are common.

- Set the stage in advance for the scope and extent of confidentiality. Share with the patient and the parents or guardians all the details about confidentiality policies and disclosure provisions.

- Inquire about parental awareness, and seek the patient’s permission to speak to the parents or, at least, encourage the patient to discuss substance use with the parents.

- In general, confidentiality often can be preserved if the minor wishes so; it may help strengthen the trust and treatment alliance between the clinician and the minor. Be aware of specific minor consent laws governing each state (see Reference section).

- Consider breaking confidentiality and engaging the parents when safety is a concern; for example, the presence of “acute danger signs” (driving while intoxicated; high amount intake, e.g., prior poisoning or overdose; combining alcohol with drugs, especially sedatives; engaging in high-risk behaviors in relation to substance use, e.g., unprotected sex and unintentional injuries) or a need for referral for further treatment can warrant such approach. In general, the clinicians should apply their best medical judgment, together with the state’s laws, to decide whether breaking confidentiality is warranted.

- Forestall situations that can unintentionally compromise confidentiality, for example, by labeling a follow-up visit as for immunizations or acne rather than “substance use.”

Alcohol Misuse Screening and Severity Assessment in Youth

The NIAAA’s Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention for Youth: A Practitioner’s Guide is a useful resource on alcohol SBI in youth.

- Strive to establish good rapport with adolescent patients and encourage honest answers. Build in alone time during the visit and explain confidentiality policies. Explain the purpose of asking ALL youth about these sensitive issues to promote a trusting relationship and alleviate the youth’s perception of being singled out.

- Ask two age-specific screening questions about friends’ and patient’s drinking in the past year and stratify risk based on responses (see Reference section).

- If negative screen, praise and encourage continuation of healthy behaviors, elicit and affirm reasons for abstinence, educate about drinking-associated risks, and jointly explore plans on how to remain alcohol free. Nondrinkers with nondrinking friends should be rescreened at least yearly, while those who drink or have drinking friends should be rescreened at each visit.

- All drinking youth should be evaluated in more depth to assess and stratify risk.

Alcohol Brief Intervention in Youth

- All drinking youth should receive advice to stop or reduce drinking. Lower- and moderate-risk patients should also receive counseling similar to that described above for the nondrinking youth.

- Highest-risk youth should receive BI. The BI principles are similar to those as for adults. A referral to addiction medicine specialty services should be considered.

- Adolescents who display “acute danger signs” (mentioned above) need immediate intervention and, likely, parental or guardian involvement.

- Follow-up is crucial for the success of attaining treatment goals. Negotiate the timing of follow-up with the patient; consider scheduling this visit for additional reasons (e.g., acne) to increase the likelihood of attendance. As with adults, start the follow-up by evaluating attainment and sustenance of alcohol use-related treatment goals and then proceed to reassessment and risk restratification. Treatment goals and plans should be revised as appropriate, as based on the newly obtained information and patient’s preferences.

CURRENT EVIDENCE ON SCREENING AND BRIEF INTERVENTION: A BRIEF SUMMARY

Screening and Brief Intervention for Unhealthy Alcohol Use

In primary care settings, SBI for alcohol misuse is a clinically effective and cost-effective preventive service with economic savings similar to screening for colorectal cancer, hypertension, or visual acuity, and to influenza or pneumococcal immunizations. Evidence suggests that SBI can reduce morbidity and mortality in problem drinkers in primary care.

The evidence for SBI in trauma settings is not as strong as for primary care. In emergency department (ED) settings, research suggests that SBI can reduce drinking and result in fewer subsequent ED visits among at-risk drinkers. Evidence on the effectiveness of alcohol SBI in general inpatient medical settings is inconclusive. Of note, the majority of general medical inpatients, identified as “positive” by screening, may have alcohol dependence for which BI is less successful. There is insufficient evidence on alcohol SBI efficacy in adolescents; however, the growing evidence is encouraging, and main professional organizations and expert panels advise conducting routine SBI in youth at least annually, starting at age 9 years.

A number of barriers can impede SBI implementation in the clinical settings. Adequate resources, staff training and nonstigmatizing, nonstereotyping identification of those at risk are the main facilitators of SBI implementation in primary care. There has been a growing support and evidence for efficacy of different ways of SBI delivery (e.g., via phone, texting, or web based), which may be particularly useful for groups who are less likely to access traditional services. The optimal interval for SBI delivery is unknown.

Screening and Brief Intervention for Unhealthy Drug Use

While some screening instruments have been validated for screening for unhealthy drug use in primary care, an important drawback is their length of administration. The Single-Question Screen holds promise in overcoming this barrier. To date, only limited research has evaluated the efficacy of SBI for unhealthy prescription-based and illicit drug use. Overall, there is some promising evidence suggesting harm reduction associated with drug SBI in primary care.

SUMMARY

The implementation of SBI in clinical settings has become a high priority for federal and other funding initiatives and health care systems. While SBIs for tobacco users and nondependent adult drinkers have been shown effective in primary care, the evidence on efficacy of drug SBI—although promising—is still inconclusive; more research is needed on the effectiveness of SBI for unhealthy drug use. The evidence for the use of SBI in youth in general medical settings has strengthened over time, and the USPSTF recommends SBI for tobacco cessation, and many professional organizations endorse alcohol SBI among adolescents.

KEY POINTS

1. Screening and brief intervention for alcohol misuse and tobacco use in primary care is an evidence-based approach to addressing these substantial public health problems.

2. With limited, but promising and growing, research evidence, screening and brief interventions for drug misuse in primary care are endorsed by many professional organizations.

3. Brief Interventions often utilize motivational interviewing techniques and are based on a harm reduction model.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. The evidence for efficacy of alcohol SBI is strongest in which clinical setting? (Choose one.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree