CANCER SCREENING

Research evidence has often been inadequate to reach definitive conclusions regarding how, when, whom, and whether to screen for various cancers. The guidelines below are a synthesis of the recommendations of the major organizations.

Breast Cancer Screening

- Breast cancer is common in the United States.

- Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed invasive cancer in US women: Approximately one in eight (12.5%) will develop breast cancer by age 90.3

- Conversely, 88% will not develop breast cancer.

- Many women greatly overestimate their risk of breast cancer. In one study, 89% of women overestimated their risk with an average estimate of 46% lifetime risk (more than triple the actual risk).4

- Conversely, 88% will not develop breast cancer.

- Breast cancer mortality in US women is second only to lung cancer; approximately 1 in 36 (2.8%) will die of breast cancer.3

- African American women have a lower incidence of breast cancer than white women, but a higher mortality rate.5

- Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed invasive cancer in US women: Approximately one in eight (12.5%) will develop breast cancer by age 90.3

- Breast cancer mortality has declined approximately 30% over the past two decades, but there is controversy about the relative roles of screening versus improved treatments.

- Risk factors for breast cancer:

- Sex—breast cancer is 100 times more common in women than men.

- Age—about 75% of breast cancers occur after age 50.

- Family history—the risk is approximately doubled with one affected first-degree relative. The risk rises if there are multiple affected family members, especially if they had early-onset breast and/or ovarian cancer (suggestive of BRCA mutations).

- Estrogen—exogenous estrogen, early menarche, late menopause, nulliparity, or late first childbirth.

- Dense breast tissue.

- History of atypical hyperplasia on biopsy.

- History of radiation therapy to the chest in childhood/adolescence.

- Obesity.

- Drinking >2 alcoholic drinks/day.

- Protective factors include parity, breast-feeding, and exercise.

- The Gail model to estimate risk is available at www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool (last accessed December 23, 2014); it is less accurate in women with a strong family history.

- Sex—breast cancer is 100 times more common in women than men.

- The benefits of screening are best proven for mammography in women ages 50 to 69.

- Women aged 40 to 49 have a lower incidence of breast cancer and denser breasts (thus lower sensitivity and specificity of screening), leading to lower predictive values. The USPSTF review stated that “for biennial screening mammography in women aged 40 to 49 years, there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is small.” They emphasized the lower incidence in this group and the adverse consequences of screening.6,7

- Data are limited for women ages 70 and over, and older women have competing causes of mortality, limiting the benefit of cancer screening.

- Women aged 40 to 49 have a lower incidence of breast cancer and denser breasts (thus lower sensitivity and specificity of screening), leading to lower predictive values. The USPSTF review stated that “for biennial screening mammography in women aged 40 to 49 years, there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is small.” They emphasized the lower incidence in this group and the adverse consequences of screening.6,7

- Potential harms from screening include the following:

- False positives leading to additional imaging.

- False positives leading to unnecessary biopsies (a decade of annual screening is estimated to result in almost 20% of women referred for a biopsy).8

- Overdiagnosis and subsequent treatment.

- Mammography is often uncomfortable and may be anxiety provoking.

- False positives leading to additional imaging.

- It has been shown in randomized trials that teaching breast self-examination (BSE) does not save lives.9 Many groups now endorse teaching “breast self-awareness” rather than formal BSE teaching.10

- Clinical breast exam (CBE) may modestly improve cancer detection rates if experienced clinicians use very careful technique.11

- Recommendations of some major groups are as follows.

- The USPSTF issued updated recommendations in 200912:

- Women aged 50 to 74 years should have mammography every 2 years.

- Screening mammography should not be done “routinely” for women ages 40 to 49 years. Women and their doctors should base the decision to start mammography before age 50 years on the risk for breast cancer and preferences about the benefits and harms.

- Current evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of CBE or screening mammography in women 75 years or older.

- The USPSTF recommends against teaching patients BSE.

- Women aged 50 to 74 years should have mammography every 2 years.

- The ACS recommends the following13:

- Ages 20 to 39: CBE every 3 years.

- Ages 40 and over: annual CBE and annual mammography.

- Optional BSEs.

- No specific upper age limit is specified. “The decision to stop screening should be individualized based on the potential benefits and risks of screening within the context of overall health status and estimated longevity.”

- Women at very high risk (>20% lifetime risk) should undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening and mammography every year. Women at moderately increased risk (15% to 20% lifetime risk) should talk to their physicians about the benefits and limitations of MRI screening in addition to yearly mammography.

- Ages 20 to 39: CBE every 3 years.

- The ACOG recommends the following10:

- Ages 20 to 39: CBE every 1 to 3 years.

- Ages 40 and over: annual CBE and annual mammography.

- Over age 75, the decision to screen should be individualized.

- “Breast self-awareness should be encouraged and can include breast self-examination.”

- Women at very high risk (>20% lifetime risk) should have “enhanced screening” with annual mammography, CBE every 6 to 12 months, instruction in BSE, and possibly MRI.

- Ages 20 to 39: CBE every 1 to 3 years.

- The USPSTF issued updated recommendations in 200912:

Cervical Cancer Screening

- The effectiveness of cervical cancer screening has never been studied in a randomized trial but is supported by strong epidemiologic evidence: the cervical cancer death rate falls in proportion to the intensity of screening. Most cases of cervical cancer occur in unscreened or inadequately screened women.

- Cervical cytologic screening may be done with the conventional Pap smear or with liquid-based tests (method does not change screening frequency).

- For some age groups, cotesting with cytology plus testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) is an option.

- HPV vaccination does not change the screening guidelines.

- The ACS, USPSTF, and ACOG have similar recommendations, as summarized below.

- Do not begin screening until age 21 years regardless of sexual history.

- Under age 21, cervical cancer is quite rare (1 to 2 per million) while HPV infection is common and dysplasia may occur but both usually spontaneously remit.

- Early screening may lead to anxiety, expense, and morbidity (excisional procedures on the cervix).

- Under age 21, cervical cancer is quite rare (1 to 2 per million) while HPV infection is common and dysplasia may occur but both usually spontaneously remit.

- Women aged 21 to 29 years should be screened every 3 years with cytology only. HPV testing would detect many transient infections without carcinogenic potential.

- Women aged 30 and older may be screened by cytology plus HPV cotesting every 5 years (preferred) or with cytology alone every 3 years.

- Women who have had a total hysterectomy (including removal of the cervix) for benign disease may stop cervical cancer screening.

- Screening may be stopped at age 65 in women who have had adequate screening (three consecutive negative Pap tests or two consecutive negative HPV/Pap cotests within past 10 years and most recent test within 5 years).

- Risk factors and special cases:

- In women with HIV infection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends cervical cytology screening twice in the 1st year after diagnosis and annually thereafter while the ACOG recommends annual cytology starting at age 21.14

- ACOG recommends that women with a history of high-grade dysplasia or cancer should continue routine age-based testing for 20 years, even past age 65.

- More frequent screening may be required in women with a history of prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) and women who are immunocompromised (such as organ transplantation).

- In women with HIV infection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends cervical cytology screening twice in the 1st year after diagnosis and annually thereafter while the ACOG recommends annual cytology starting at age 21.14

Colorectal Cancer Screening

- Colorectal cancer (CRC) has a lifetime incidence of about 5%, and about one-third of those will die from it, making CRC the third leading cancer killer of men and of women (second for men and women combined).

- Screening for CRC is associated with decreases in incidence as well as mortality, due to removal of premalignant adenomatous polyps, but only about two-thirds of Americans have been screened adequately.15

- CRC is more common in men (35% higher than in women), in African Americans (25% higher than in Whites), and with advancing age (90% diagnosed after age 50).5

- Other risk factors include:

- Personal history of CRC or adenomatous polyps (especially if polyps are multiple, large [>1 cm], or villous/tubulovillous).

- Family history of polyps or CRC. The risk is doubled for those with one first-degree relative with CRC and further increased for those with multiple affected relatives or relatives with early-onset CRC (age <50).

- Genetic syndromes including familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and the Lynch syndrome/hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome.

- Inflammatory bowel disease, especially ulcerative colitis with pancolitis.

- History of abdominal radiation therapy in childhood.

- There may be an increased risk of CRC associated with obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking, physical inactivity, and dietary factors (red meat, low fiber, few fruits and vegetables, low dairy).

- Personal history of CRC or adenomatous polyps (especially if polyps are multiple, large [>1 cm], or villous/tubulovillous).

- Data suggest a protective effect for the use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Screening strategies fall into 2 main categories:

- Stool-based tests that primarily detect cancer: guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), or stool DNA testing

- Tests that detect both cancer and adenomatous polyps, thus permitting polyp removal for cancer prevention: flexible sigmoidoscopy (FSIG), colonoscopy, barium enema, or CT colonography

- Stool-based tests that primarily detect cancer: guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT), fecal immunochemical test (FIT), or stool DNA testing

- For any test other than colonoscopy, any abnormalities must be followed up with a full colonoscopy, not just repeat testing.

- A brief summary of screening tests and recommended intervals includes:

- Annual gFOBT with a high sensitivity test such as Hemoccult SENSA (not Hemoccult II):

- Home collection of three specimens (in-office rectal exam is not an acceptable stool test for CRC screening).

- Modest test sensitivity and specificity but has been shown in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to lower CRC mortality.

- Home collection of three specimens (in-office rectal exam is not an acceptable stool test for CRC screening).

- Annual FIT, which detects human globin from lower GI bleeding (globin from upper GI sources is digested) and is therefore more specific.

- Stool DNA test, interval uncertain.

- FSIG every 5 years:

- Requires a limited bowel prep; no sedation required.

- Colonic perforation is rare (<1 in 20,000).

- Only examines the distal colon but has been shown to lower CRC mortality.

- Requires a limited bowel prep; no sedation required.

- Air contrast barium enema (ACBE) every 5 years:

- Requires a full bowel prep; no sedation is used and the test may be uncomfortable.

- Sensitivity is much lower than colonoscopy.

- Requires a full bowel prep; no sedation is used and the test may be uncomfortable.

- Computed tomography colonography (CTC) or “virtual colonoscopy” every 5 years:

- Requires a full bowel prep and air insufflation.

- Sensitivity is probably comparable to colonoscopy.

- Patients with large polyps must be referred for colonoscopic resection, but uncertainty exists about management of small (<6 mm) polyps.

- Requires a full bowel prep and air insufflation.

- Colonoscopy every 10 years:

- Requires a full bowel prep and sedation.

- Regarded as the gold standard, but may miss 5% to 12% of lesions >1 cm.

- Lesions can be resected during the procedure.

- Risk of colonic perforation is about 1 in 1,000 and also can cause bleeding and cardiovascular complications.

- Requires a full bowel prep and sedation.

- Annual gFOBT with a high sensitivity test such as Hemoccult SENSA (not Hemoccult II):

- Current guidelines were published in 2012 by the ACP,16 in 2008 by the USPSTF,17 and in 2008 by a joint guideline18 published by ACS, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology.

- The USPSTF recommendations include the following:

- Screen adults ages 50 to 75 using annual high-sensitivity gFOBT, or sigmoidoscopy every 5 years combined with high-sensitivity gFOBT every 3 years, or colonoscopy every 10 years.

- Do not routinely screen those aged 76 to 85 years, but there may be considerations that support screening in an individual patient.

- Screening is not recommended >85 years of age.

- Screen adults ages 50 to 75 using annual high-sensitivity gFOBT, or sigmoidoscopy every 5 years combined with high-sensitivity gFOBT every 3 years, or colonoscopy every 10 years.

- The ACP recommends that

- Clinicians perform individualized assessment of risk for CRC in all adults.

- Average-risk adults should start CRC screening at age 50, using annual gFOBT, annual FIT, FSIG every 5 years, or colonoscopy every 10 years.

- High-risk adults should start screening with colonoscopy at age 40 or 10 years younger than the age at which the youngest affected relative was diagnosed with CRC.

- Screening should stop at age 75 or if life expectancy is <10 years.

- Clinicians perform individualized assessment of risk for CRC in all adults.

- The joint guideline recommends that

- Screening for CRC in average risk, asymptomatic adults should begin at age 50.

- CRC screening is not appropriate if the patient is not likely to benefit from screening due to life-limiting comorbidity.

- Colon cancer prevention should be the primary goal of screening.

- Acceptable screening tests include annual gFOBT with a high sensitivity test, or annual FIT, or stool DNA test, interval uncertain.

- Preferred tests detect adenomatous polyps and can prevent cancer: FSIG every 5 years, ACBE every 5 years, CTC every 5 years, or colonoscopy every 10 years.

- Screening for CRC in average risk, asymptomatic adults should begin at age 50.

- High-risk persons need earlier and/or more frequent screening. These include those with a personal history of CRC or adenomatous polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, endometrial cancer before age 50, a hereditary CRC syndrome, or a strong family history of CRC or polyps.

- For those with CRC or adenomatous polyps in a first-degree relative <60 years or in two first-degree relatives of any age, they should be screened with colonoscopy every 5 years. Screening should begin at age 40, or 10 years before the youngest case in the immediate family, whichever is earlier.

- For those with CRC or adenomatous polyps in a first-degree relative at 60 or older, or two second-degree relatives with CRC, screening should begin at age 40 with any recommended form of testing at the usual intervals.

- For those with CRC or adenomatous polyps in a first-degree relative <60 years or in two first-degree relatives of any age, they should be screened with colonoscopy every 5 years. Screening should begin at age 40, or 10 years before the youngest case in the immediate family, whichever is earlier.

Lung Cancer Screening

- Lung cancer is the number one cause of cancer-related death in men and in women. Approximately 90% of cases occur in current or former smokers; smoking cessation is the single most important factor in reducing lung cancer mortality.

- Multiple randomized trials have demonstrated no mortality benefit to screening with plain chest radiography (CXR), with or without sputum cytology.

- Observational trials in the late 1990s showed that low-dose (2 mSv), single breath-hold, helical CT (LDCT) scans could detect early-stage lung cancers much more effectively than CXRs.

- The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) published in 2011 was the first randomized trial to show a statistically significant benefit to CT screening for lung cancer.19

- The trial compared annual LDCT to CXR for 3 years in more than 50,000 people ages 55 to 74; participants had at least 30 pack-years of smoking, including current smokers and former smokers who had quit within 15 years.

- At a median follow-up of 6.5 years, there was a relative mortality reduction of 20% for lung cancer deaths and 6.7% reduction in all-cause mortality in the LDCT group.

- To prevent one lung cancer death, the number needed to screen with LDCT was 320.

- A substantial number of participants had an abnormal screening test (24% in the LDCT group and 6.9% in the CXR group), >90% of which were false positives. Most only required additional imaging, but some subjects required invasive procedures, including surgery. Complications from the diagnostic workup occurred at a low rate, about 1.5% of the participants who had abnormal screening tests.

- The trial compared annual LDCT to CXR for 3 years in more than 50,000 people ages 55 to 74; participants had at least 30 pack-years of smoking, including current smokers and former smokers who had quit within 15 years.

- Lung cancer screening recommendations are in evolution. The USPSTF guidelines are undergoing review.

- A number of expert organizations have issued at least preliminary guidelines, including the ACS,20 the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,21 American College of Chest Physicians,22 and others. In general, they support LDCT screening in individuals similar to those in the NLST:

- Ages 55 to 74.

- At least 30-pack-years of smoking.

- Current smoker or quit within the past 15 years.

- Screening is not appropriate for patients with severe comorbidities that limit life expectancy or would preclude potentially curative treatment.

- The decision to start screening should be preceded by a process of informed and shared decision making, with discussion of the potential benefits, limitations, and harms associated with screening.

- Ages 55 to 74.

Prostate Cancer Screening

- Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in US men and is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in US men, with a lifetime risk of about 1 in 6.

- The incidence increases with age. There is a higher incidence and earlier age of onset in African American men. The risk is higher in those with affected first-degree relatives or inherited cancer syndromes such as BRCA or Lynch syndrome (HNPCC).

- Although 17% of men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, only 2.4% will die of it.

- Screening for prostate cancer is a controversial topic. Randomized controlled trials have shown small or no survival benefit in screened groups. Many men die “with” rather than “of” prostate cancer. Treatment has potential harms, including erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, and bowel problems.

- The USPSTF recommends against prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, concluding that screening produces more harms than benefits.23

- The ACS stresses the need for informed decision making with adequate provision of information about the uncertainties, risks, and potential benefits associated with prostate cancer screening.24

- This information should be provided starting at age 50 (at 40 to 45 in higher-risk men).

- Men with <10-year life expectancy should not be offered prostate cancer screening. At age 75, only about half of men have a life expectancy of 10 years or more.

- Key discussion points include the following:

- Screening may be associated with a reduction in the risk of dying from prostate cancer; however, evidence is conflicting and experts disagree about the value of screening.

- Not all men whose prostate cancer is detected through screening require immediate treatment. It is not currently possible to predict which men are likely to benefit from treatment.

- Treatment for prostate cancer can lead to urinary, bowel, sexual, and other health problems. These problems may be significant or minimal, permanent, or temporary.

- The PSA and digital rectal exam (DRE) may produce false-positive or false-negative results.

- Abnormal results require prostate biopsies that can be painful, may lead to complications like infection or bleeding, and can miss clinically significant cancer.

- Screening may be associated with a reduction in the risk of dying from prostate cancer; however, evidence is conflicting and experts disagree about the value of screening.

- If screening is elected, the ACS recommends PSA with or without DRE.

- Initial PSA <2.5 ng/mL: screen every 2 years.

- Initial PSA ≥2.5 ng/mL: screen annually.

- PSA >4.0 ng/mL: refer for biopsy (2.5 to 4.0 ng/mL, individualized assessment).

- Initial PSA <2.5 ng/mL: screen every 2 years.

- This information should be provided starting at age 50 (at 40 to 45 in higher-risk men).

- The ACP recommends that PSA testing should only be done in patients with a clear preference for screening.25

- Clinicians should inform men ages 50 to 69 about the limited potential benefits and substantial harms of screening for prostate cancer.

- Screening should not be done in average-risk men aged <50 or >69 nor those with a life expectancy of <10 to 15 years.

- Clinicians should inform men ages 50 to 69 about the limited potential benefits and substantial harms of screening for prostate cancer.

- The American Urological Association (AUA) published its guideline online in 2013.26 Recommendations include:

- Men <40 years of age should not be screened.

- Average-risk men <55 years of age should not be routinely screened. For men 40 to 55 years of age who are at higher risk (family history or African American), decisions should be individualized.

- For men ages 55 to 69, they strongly recommend shared decision making, based on a man’s values and preferences after weighing the benefits against the known potential harms associated with screening and treatment. One prostate cancer death is averted for every 1,000 men screened for a decade.

- Men should not be routinely screened if they are >70 years of age or have a life expectancy <10 to 15 years. Some men aged >70 years who are in excellent health may benefit from prostate cancer screening.

- If men choose PSA screening, an interval of 2 years or more may be preferred over annual screening as it is expected that screening intervals of 2 years preserve the majority of the benefits and reduce overdiagnosis and false positives. Intervals for rescreening can be individualized by a baseline PSA level.

- There is no evidence that DRE is beneficial as a primary screening test.

- Men <40 years of age should not be screened.

Ovarian Cancer Screening

- Ovarian cancer is uncommon (2% lifetime risk) but often lethal because only 15% are diagnosed while still localized to the ovary.27 Detection is hampered by the deep anatomic location of the ovary and because ovarian cancer is often multifocal and extraovarian, even at early stages.

- Risk factors for ovarian cancer include:

- Family history, especially the inherited cancer syndromes (BRCA, Lynch syndrome). The BRCA1 gene mutation conveys a lifetime risk of about 40%, and the BRCA2 gene mutation conveys a lifetime risk of about 20%.

- Other risk factors include a history of infertility, polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy, and cigarette smoking.

- Protective factors include past use of oral contraceptives, history of breast-feeding >12 months, previous pregnancy, tubal ligation, and hysterectomy.

- Family history, especially the inherited cancer syndromes (BRCA, Lynch syndrome). The BRCA1 gene mutation conveys a lifetime risk of about 40%, and the BRCA2 gene mutation conveys a lifetime risk of about 20%.

- Pelvic examination is not effective for screening due to poor sensitivity and specificity.

- Ovarian cancer is occasionally found incidentally on a Pap smear (sensitivity <30%).

- The tumor marker CA 125 has limited sensitivity and specificity.

- Only about half of early ovarian cancers have elevated levels of CA 125.

- False positives are too common (about 1%) for an effective screening test. Levels vary with the menstrual cycle, age, ethnicity, and smoking, and CA 125 can be increased with endometriosis, uterine leiomyomata, cirrhosis, ascites from any cause, and a variety of cancers.

- Assessment of changes in CA 125 levels over time may have better test characteristics.

- Only about half of early ovarian cancers have elevated levels of CA 125.

- Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) has limited sensitivity and specificity for ovarian cancer screening.

- A large randomized trial in the US showed that screening with CA 125 and TVU did not improve ovarian cancer mortality (relative risk 1.18, screened vs. usual care).28 Positive predictive value was only about 1%. For every screen-detected ovarian cancer, approximately 20 women underwent surgery; 20% of those surgeries resulted in major complications.

- No organization recommends screening average-risk women for ovarian cancer.

- The USPSTF specifically recommends against screening due to lack of benefit and potential harms (unnecessary surgeries).29

- ACOG concluded that currently, there is no effective strategy for ovarian cancer screening.30 Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion when women present with symptoms commonly associated with ovarian cancer: pelvic or abdominal pain, increase in abdominal size or bloating, and difficulty eating or feeling full. High-risk women may be offered the combination of pelvic examination, TVU, and CA 125 testing.

- The USPSTF specifically recommends against screening due to lack of benefit and potential harms (unnecessary surgeries).29

Testicular Cancer

- USPSTF recommends against screening for testicular cancer in adolescent or adult males.

- The incidence is low (approximately 1% of cancers in men).

- Testicular germ cell tumors are one of the most curable solid neoplasms (overall cure rate >90%).

- No evidence has shown that routine screening would improve health outcomes.

- The incidence is low (approximately 1% of cancers in men).

- The AUA recommends monthly testicular self-exams.

Screening for Other Cancers

- Routine population screening is not recommended for the following cancers: endometrial, testicular, bladder, thyroid, oral cavity, or skin. Clinicians should be vigilant for early symptoms of possible cancer in those sites.

- The ACS recommends that “the cancer-related checkup should include examination for cancers of the thyroid, testicles, ovaries, lymph nodes, oral cavity, and skin, as well as health counseling about tobacco, sun exposure, diet and nutrition, risk factors, sexual practices, and environmental and occupational exposures.”

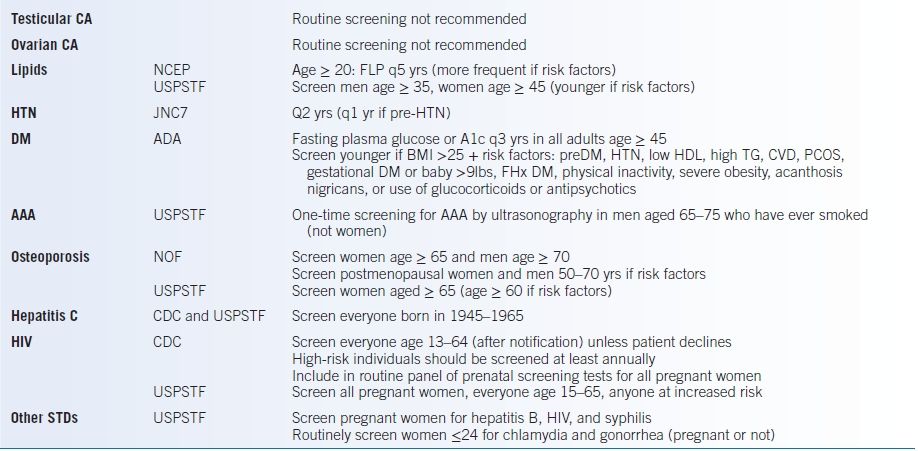

SCREENING FOR OTHER CONDITIONS

Hypertension

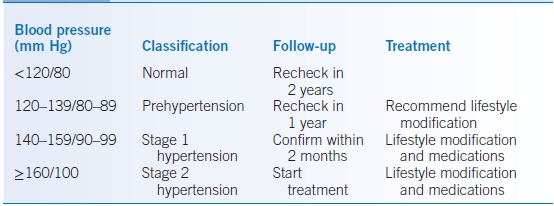

- The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends that all patients should have their blood pressure (BP) measured every 2 years.31 See Table 5-2 for the classification of BP levels. JNC 8 does not specifically address screening or classification.

- Lifestyle modification includes counseling on weight loss, aerobic exercise, limiting alcohol intake, and reduction in sodium intake.

- Treatment of hypertension is discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

TABLE 5-2 Classification, Follow-Up, and Treatment of Hypertension

Data from Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003;289:2560-2572.

Dyslipidemia

- The recent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment recommend screening those aged 20 to 79 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease every 4 to 6 years and estimating the 10-year risk.32 The risk calculator may be found at http://tools.cardiosource.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator/ (last accessed December 23, 2014).

- The USPSTF strongly recommends screening for lipid disorders starting at age 35 in men and age 45 in women. Younger adults should be screened if they have other risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD).

- The treatment of dyslipidemia is discussed in detail in Chapter 11.

Diabetes Mellitus

- The American Diabetes Association annually updates recommendations for diabetes mellitus (DM) care. The 2013 guidelines that recommend screening are presented here.33

- The A1C, fasting plasma glucose, or 75-g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) are all acceptable screening tests. Healthy adults should be tested starting at age 45.

- Consider testing all adults who are overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) and have additional risk factors: hypertension, HDL cholesterol <35 mg/dL or triglyceride level >250 mg/dL, cardiovascular disease, women with polycystic ovary syndrome, previous A1C ≥5.7%, impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose, women who delivered a baby weighing >9 pounds or who were diagnosed with gestational DM, physical inactivity, first-degree relative with DM, high-risk ethnicity (e.g., African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander), and other risk conditions (e.g., severe obesity, acanthosis nigricans, or use of glucocorticoids or antipsychotics).

- If results are normal, testing should be repeated at least every 3 years, with consideration of more frequent testing depending on initial results and risk status.

- Those with prediabetes should be tested yearly:

- A1C 5.7% to 6.4%

- Fasting glucose 100 to 125 mg/dL

- OGTT 2-hour value of 140 to 199 mg/dL

- A1C 5.7% to 6.4%

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

- The USPSTF recommends one-time screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) by ultrasonography in men aged 65 to 75 years who are current or former smokers.34

- They make no recommendation for or against screening for AAA in patients with no smoking history.

- They recommend against routine screening for AAA in women.

Coronary Heart Disease

- The USPSTF recommends against routine screening with resting ECG or exercise treadmill test for the prediction of CHD in low-risk adults and found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening in adults at intermediate or high risk for CHD events.35 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the use of nontraditional risk factors such as C-reactive protein (CRP), ankle-brachial index (ABI), coronary artery calcification (CAC) score on electron beam CT, homocysteine level, or lipoprotein(a) level.36

- As noted above, recent ACC/AHA guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment recommend screening those ages 20 to 79 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease every 4 to 6 years for risk factors and estimating the 10-year risk.32 Additionally, if a risk-based treatment decision is unclear, high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) (≥2 mg/L), CAC scoring (≥300 Agatston units or ≥75th percentile for age, sex, and ethnicity), or ABI (<0.9) may provide further guidance. Lipoprotein(a), albuminuria, renal function, cardiorespiratory fitness testing, and carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) are of unclear or limited value.

Peripheral Arterial Disease

- The USPSTF recommends against routine screening for peripheral arterial disease (PAD) because there is little evidence that treatment of PAD at this asymptomatic stage of disease, beyond treatment based on standard cardiovascular risk assessment, improves health outcomes.37

- As noted, the ACC/AHA has said that measurement of the ABI is reasonable for cardiovascular risk assessment in asymptomatic adults for whom risk-based treatment decisions are unclear.32

Thyroid Disease

Screening for thyroid disease is not routinely recommended, but clinicians should keep a low threshold for measurement of thyroid-stimulating hormone for subtle or nonspecific symptoms, especially in older women (see Chapter 21).

Obesity

- Periodic height and weight measurements are recommended for all patients.

- The body mass index (BMI) is the body weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

- BMI 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 is considered normal.

- BMI >25 kg/m2 is considered overweight.

- BMI 30 to 34.9 kg/m2 is class I obesity.

- BMI 35 to 39.9 kg/m2 is class II obesity.

- BMI ≥40 kg/m2 is class III or morbid obesity.

- BMI 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2 is considered normal.

- BMI may overestimate the degree of obesity in extremely muscular individuals (such as professional athletes).

- For persons with a BMI of 25 to 35, it can be useful to measure the waist circumference. Increased morbidity is associated with waist >102 cm (40 inches) in men and 88 cm (35 inches) in women.

Osteoporosis

- The USPSTF recommends screening for osteoporosis in38:

- Women age ≥65 years.

- Women <65 years whose risk factors put them at a fracture risk equivalent to a 65-year-old white woman.

- Evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for osteoporosis in men.

- Women age ≥65 years.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends39:

- All postmenopausal women and men ≥50 should be evaluated for osteoporosis risk and risk for falling.

- Bone mineral density (BMD) testing should be considered for

- All women ≥65 and men ≥70

- Persons with clinical risk factors for fracture if they are men ages 50 to 69 and postmenopausal or perimenopausal women

- Adults with a fracture after age 50

- Adults with a condition (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) or taking a medication associated with bone loss (e.g., glucocorticoids equivalent to ≥5 mg/day prednisone for 3 or more months)

- All women ≥65 and men ≥70

- All postmenopausal women and men ≥50 should be evaluated for osteoporosis risk and risk for falling.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- The CDC website, www.cdc.gov (last accessed December 23, 2014), has up-to-date recommendations about screening for sexually transmitted disease (STD). Basic guidelines are as follows:

- Sexually active men who have sex with men (MSM) should be screened annually for HIV (in uninfected patients) and for bacterial STDs, such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

- MSM who engage in higher-risk behaviors (such as multiple or anonymous partners, or sex in conjunction with illicit drug use) should be screened every 3 to 6 months.

- Sexually active females aged ≤25 years should be screened for chlamydia testing annually and gonorrhea testing annually for those at risk.

- Sexually active men who have sex with men (MSM) should be screened annually for HIV (in uninfected patients) and for bacterial STDs, such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

- HIV screening:

- HIV testing should be encouraged for adolescents who are sexually active and those who use injection drugs.

- Individuals aged 13 to 64 should get tested at least once in their lifetimes and those with risk factors get tested at least annually.

- The USPSTF also supports widespread HIV screening for persons aged 15 to 65 years (younger adolescents and older adults who are at increased risk should also be screened), and for all pregnant women.40

- HIV testing should be encouraged for adolescents who are sexually active and those who use injection drugs.

Hepatitis C

The CDC and USPSTF recommend that everyone born 1945–1965 be screened for hepatitis C.41

Alcohol Abuse and Dependence

- Screening for alcohol abuse and dependence is an important part of the routine checkup (see Chapter 46).

- Definitions (from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at www.niaaa.nih.gov, last accessed December 23, 2014):

- Heavy or at-risk drinking is diagnosed in the following group:

- Men who consume >14 drinks per week or >4 drinks per occasion

- Women who consume >7 drinks per week or >3 drinks per occasion

- Elderly who consume >7 drinks per week or >3 drinks per occasion

- Men who consume >14 drinks per week or >4 drinks per occasion

- One drink is 12 g ethanol, as in 12 oz of beer, 5 oz of wine, or 1.5 oz of distilled spirits.

- Alcohol abuse is a maladaptive pattern of use; manifested by continued or recurrent use despite failure in major role obligations at work, school, or home; of use in physically hazardous situations, or of use despite alcohol-related legal, social, or interpersonal problems.

- Alcohol dependence is marked by tolerance, the presence of withdrawal symptoms on cessation, impaired control (drinking more/longer than intended), persistent desire, and continued use despite physical or psychological problems related to alcohol.

- Heavy or at-risk drinking is diagnosed in the following group:

- The CAGE questions are a useful screening tool for alcohol dependence. Two positive responses are considered a positive test and indicate further assessment is warranted.

- Have you ever felt that you should Cut down on drinking?

- Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt bad or Guilty about your drinking?

- Eye-opener: Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover?

- Have you ever felt that you should Cut down on drinking?

Adult Immunizations

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Guidelines are subject to change over time and according to local public health conditions.

- Each patient’s clinical context should be considered and risks and benefits weighed.

- The following are general guidelines, and manufacturer’s information should be consulted regarding individual products.

- Various professional organizations make recommendations regarding immunization practices. The official national policy is determined by the following:

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

- The ACIP makes recommendations that are then reviewed by the director of the CDC and HHS. They become official policy when published in CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports.

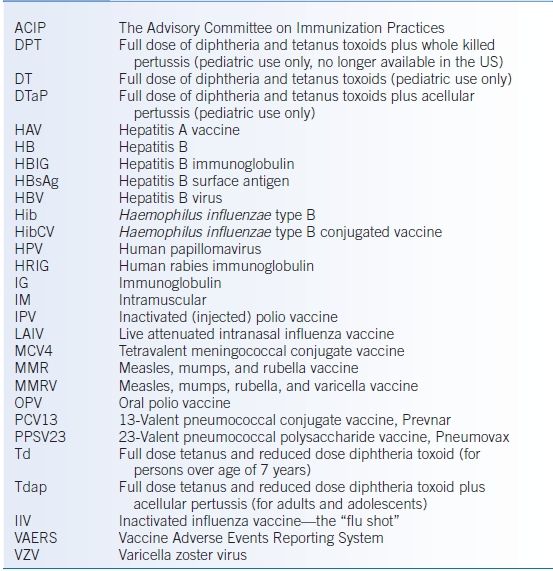

- Table 5-3 lists abbreviations used in this chapter regarding immunizations.

TABLE 5-3 Glossary of Vaccine-Related Abbreviations

RESOURCES FOR INFORMATION

Immunization guidelines are quite detailed and are periodically updated. Useful resources for accessible, up-to-date information include the following:

- The CDC vaccine information website (www.cdc.gov/vaccines, last accessed December 23, 2014) has extensive information including the General Recommendations on Immunization and recommendations for specific vaccines.

- The CDC publishes an adult immunization schedule annually (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html, lasted accessed December 23, 2014).

- “The Pink Book: Epidemiology & Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases” contains a wealth of information and is available in PDF format at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/index.html (last accessed December 23, 2014).

- The Immunization Action Coalition (IAC) website has educational materials, camera-ready and copyright-free, at www.immunize.org. They also have many translated documents for non–English-speaking patients. They have comprehensive vaccine information for the public at www.vaccineinformation.org (last accessed December 23, 2014).

LEGAL RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE PROVIDER

- Serious or unusual adverse events must be reported to the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS), whether or not the provider thinks they are causally associated. Forms are available from the Food and Drug Administration at www.fda.gov/cber/vaers/vaers.htm (last accessed December 23, 2014).

- Federally approved Vaccine Information Statement must be given to all patients prior to administering vaccines. Copies are available from the CDC or at www.immunize.org (last accessed December 23, 2014).

- Permanent vaccination records must be maintained by all vaccine providers.

TIMING OF ADMINISTRATION

- Specified times are minimum intervals.

- Doses that are administered at shorter intervals may not result in adequate antibody response and should not be counted as part of a primary series.

- Delay or interruption in the immunization schedule does not require starting over or extra doses.

- Doses that are administered at shorter intervals may not result in adequate antibody response and should not be counted as part of a primary series.

- Simultaneous administration of multiple vaccines improves compliance.

- In general, inactivated (killed) and most live vaccines can be administered at the same time at separate anatomic sites.

- Live parenteral vaccines (see Table 5-4) and live intranasal influenza vaccine (LAIV) should be administered at the same visit or should be separated by at least 4 weeks.

- Live oral vaccines (such as oral typhoid) may be given at any time before or after live parenteral vaccines or LAIV.

- Tuberculin test response can be inhibited by live virus vaccines. Tuberculin skin testing can be done on the same day as the vaccination or 4 to 6 weeks later.

- In general, inactivated (killed) and most live vaccines can be administered at the same time at separate anatomic sites.

- Antibody-containing blood products can interfere with the response to live virus vaccines, particularly measles and varicella (but not the zoster vaccine). The interactions can be complex, so the clinician should consult the CDC website, specifically the Pink Book, Chapter 2.

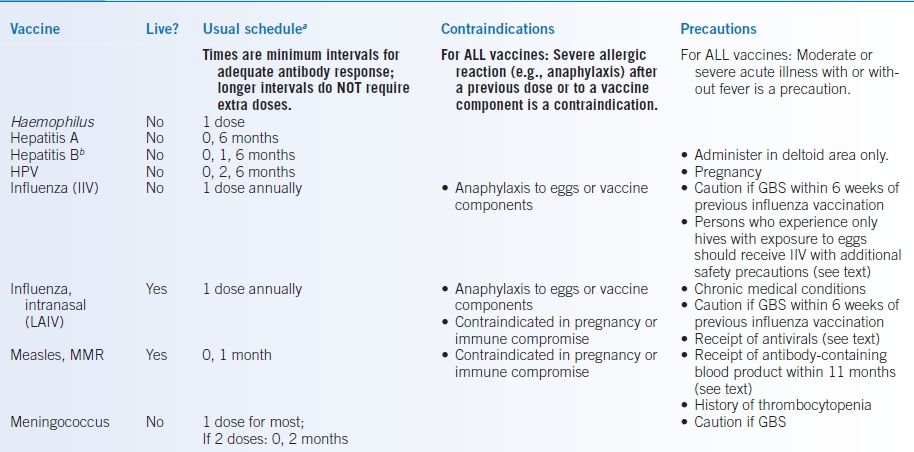

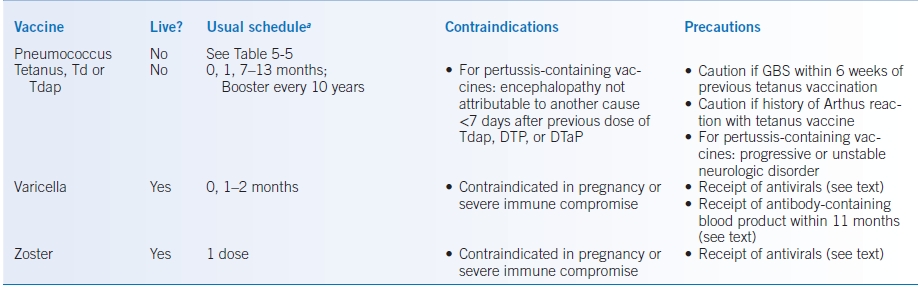

TABLE 5-4 Adult Immunizations

aFirst dose at time “0 month.”

bSee text for schedule for hemodialysis patients.

DTap, full dose diphtheria/tetanus toxoid plus acellular pertussis (pediatric only); DTP, full dose diphtheria/tetanus toxoid plus whole killed pertussis (pediatric only, no longer available in US) HPV, human papillomavirus; GBS, history of Guillain-Barré syndrome; IM, intramuscularly; IIV, inactivated influenza vaccine (injected); LAIV, live attenuated intranasal influenza vaccine MMR, measles, mumps, and rubella; Tdap, tetanus and reduced dose diphtheria toxoid with acellular pertussis vaccine; Td, tetanus and reduced dose diphtheria toxoids.

DOCUMENTATION OF PRIOR VACCINATIONS

- If records cannot be located, an age-appropriate schedule of so-called catch-up immunizations should be started. Persons who have served in the military usually have been vaccinated against measles, rubella, tetanus, diphtheria, and polio.

- Self-reported doses of influenza vaccine and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine are acceptable.

- Vaccines received outside the US are usually of adequate potency. Foreign records are acceptable if they include written documentation of the date of vaccination, and the schedule (age and interval) was comparable with that recommended in the United States.

HYPERSENSITIVITY TO VACCINE COMPONENTS

- Persons with a history of anaphylactic reactions to any vaccine component should not receive that vaccine, except under the supervision of an experienced allergist. Vaccines may have traces of egg protein or antibiotics; the manufacturer’s insert should be carefully checked.

- Contact dermatitis to neomycin is a delayed-type (cell-mediated) immune response, not anaphylaxis, and is therefore not a contraindication to vaccine use.

- Hypersensitivity to thimerosal is usually a local delayed-type or an irritant effect.

- Many vaccines may cause mild-to-moderate local or systemic adverse effects such as low-grade fever or injection site swelling, redness, or soreness. These are not a contraindication to future doses of the vaccine.

SPECIFIC VACCINES AND IMMUNOBIOLOGIC AGENTS

See the Specific Patient Groups section for age-based checklists and recommendations for persons who have chronic illnesses, are immunocompromised, are pregnant or breast-feeding, or are health care workers or travelers. Table 5-4 provides an overview of the schedules and contraindications.

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella

Indications

- Ensure that all adults are immune to measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR). Documentation of physician-diagnosed disease is not adequate evidence of immunity.

- Adequate evidence of immunity to measles or mumps can include any of the following:

- Documentation of at least 1 dose of live measles/mumps vaccine on or after the first birthday.

- Serologic evidence of immunity.

- Persons born before 1957 are considered immune, unless they are health care workers.

- Documentation of at least 1 dose of live measles/mumps vaccine on or after the first birthday.

- Adequate evidence of immunity to rubella requires the following:

- Documentation of at least 1 dose of rubella vaccine on or after the first birthday

- Serologic evidence of immunity

- Documentation of at least 1 dose of rubella vaccine on or after the first birthday

- Nonimmune persons should receive 1 dose of MMR, especially women of childbearing years.

- A second dose of MMR (>1 month after first dose) is recommended for:

- Prior recipients of a killed measles vaccine or an unknown type from 1963 to 1967

- Health care workers (unless serologic evidence of immunity)

- All students (unless serologic evidence of immunity)

- Persons who travel outside the US

- HIV-infected persons without immunity to measles, rubella, and mumps, if the CD4 lymphocytes are ≥15% and ≥200/μL for ≥6 months

- Prior recipients of a killed measles vaccine or an unknown type from 1963 to 1967

Postexposure Prophylaxis

- Live measles vaccine may prevent disease if given within 72 hours of exposure.

- Immune globulin (IG) may prevent or modify disease and provide temporary protection if given within 6 days of exposure.

- The dose is 0.25 mL/kg IM (maximum of 15 mL).

- Immunocompromised persons, irrespective of evidence of measles immunity, should receive 0.5 mL/kg IM (maximum 15 mL).

- After administration of IG, the passively acquired measles antibodies can interfere with the immune response to measles vaccination, so vaccination should be delayed for 6 months.

- The dose is 0.25 mL/kg IM (maximum of 15 mL).

Contraindications, Side Effects, and Precautions

- MMR is a live attenuated virus and is therefore contraindicated in pregnancy. Pregnancy should be avoided for 3 months after MMR-containing vaccine. Close contact with a pregnant woman or immunocompromised person is not a contraindication to MMR vaccination (the vaccine is not shed).

- MMR is generally contraindicated in immunocompromised hosts. HIV-infected persons may be vaccinated with MMR if they lack evidence of measles immunity, are asymptomatic, and are not severely immunosuppressed (for adults CD4 lymphocytes ≥200/μL or >14%).

- Persons who have experienced a severe allergic reaction to a vaccine component or following a prior dose of measles vaccine should generally not be vaccinated with MMR.

- In the past, persons with a history of anaphylaxis to eggs were considered to be at increased risk for serious reactions from measles or mumps vaccines. However, anaphylactic reactions to these vaccines are not associated with hypersensitivity to egg antigens but to other components of the vaccines (such as gelatin or neomycin).

- MMR may be administered to egg-allergic persons without prior routine skin testing or the use of special protocols.42

- In the past, persons with a history of anaphylaxis to eggs were considered to be at increased risk for serious reactions from measles or mumps vaccines. However, anaphylactic reactions to these vaccines are not associated with hypersensitivity to egg antigens but to other components of the vaccines (such as gelatin or neomycin).

- Moderate or severe acute illness with or without fever is a precaution. Mild acute illness and low-grade fever are not contraindications to immunization.

- Adverse reactions may include fever (5% to 15%), rash (5%), arthralgias (up to 25% of adult females), or rarely thrombocytopenia or lymphadenopathy.

- Because blood products can interfere with the antibody response, MMR administration should be delayed (consult the CDC for exact intervals). However, rubella-susceptible women should be vaccinated immediately postpartum even if anti-Rho(D) (RhoGAM, WinRho, etc.) or other blood products were administered during pregnancy or at delivery. Antibody levels should be measured 3 months later to assess response.

- Tuberculin test response can be inhibited by live virus vaccines; tuberculosis skin testing can be done on the same day as the vaccination or 4 to 6 weeks later.

Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Pertussis Vaccines

Indications

- All adults of any age should complete a primary series of 3 doses of Td if they have not done so during childhood or if the vaccination history is uncertain.

- Tetanus vaccine was first widely used in the 1940s, so elderly persons may have never received a primary series.

- Doses that are given as part of wound management do count toward the 3 doses needed.

- Tetanus vaccine was first widely used in the 1940s, so elderly persons may have never received a primary series.

- A tetanus booster is recommended every 10 years, lifelong. Many adults are overdue for boosters.

- Only about one-third of tetanus cases result from puncture wounds; other sources include minor wounds, burns, frostbite, bullet wounds, crush injuries, and even chronic wounds such as abscesses and chronic ulcers (14% of cases). Approximately 4% of patients with tetanus recall no antecedent wound.

- Because infection does not confer complete immunity, tetanus patients should be immunized after recovery.

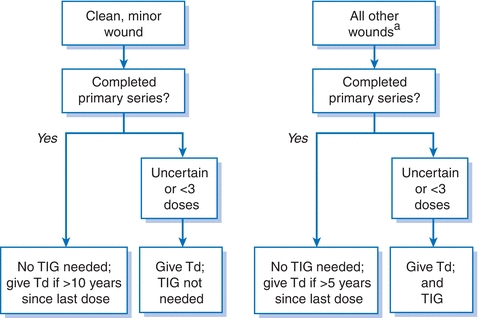

- See Figure 5-1 for guidelines for postexposure prophylaxis.

Figure 5-1 Guidelines for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent tetanus. aTetanus-producing wounds are often not the classic puncture wounds but can include minor wounds, burns, frostbite, bullet wounds, crush injuries, and chronic wounds such as abscesses and chronic ulcers. TIG, tetanus immunoglobulin; Td, tetanus and diphtheria toxoids, adsorbed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree