- the principles behind screening for disease;

- the notion that screening is a programme and not a test;

- screening can cause harm as well as benefit;

- the need for controlled trials to evaluate screening;

- the key biases that need to be considered in interpreting data;

- the need for balanced information to inform the public about screening.

History of screening

The first UK screening programmes were for communicable diseases, for example ‘mass miniature radiography’ for detecting tuberculosis. The aim was mainly to prevent disease transmission. Direct benefit to the screened individual was secondary. The TB screening programme stopped once prevalence became low.

The first UK noncommunicable disease screening was cervical cytology testing introduced in the 1960s. Back then there was little recognition of the complexity of delivering a comprehensive screening programme, and for the first two decades of its existence the cervical screening programme was highly controversial, made little or no impact on deaths from cervical cancer, and led to considerable overtreatment of inconsequential symptomless tissue change.

The lessons from this experience were taken to heart and led to the establishment in the 1990s of the UK National Screening Committee (NSC). The NSC aim is to ensure that sound evidence underpins all screening policy, and that all screening programmes are delivered according to rigorous quality standards. Criteria, modified from the 1968 World Health Organisation’s Wilson’s Criteria, are used by the NSC to help assess which potential screening programmes could be worthwhile (see Appendix 16.1 for the detailed list).

To evaluate the pros and cons of a screening programme, one must understand:

- what screening is;

- what screening does;

- why good-quality research is essential before introducing screening;

- what a practising doctor needs to know for advising his or her patients.

What is screening?

In a nutshell, screening means tests done on healthy people to reduce their risk of a nasty health outcome in the future.

A more careful version of this explanation is that screening means:

- tests or inquiries;

- it is performed on people who do not have (are asymptomatic) or have not recognised the signs or symptoms of the condition being tested for;

- it is carried out where the stated or implied purpose is to reduce risk for such individuals of future ill health in relation to the condition being tested for; or

- it is carried out to give information about risk that is deemed valuable for such individuals even though risk cannot be altered.

Screening is thus a form of secondary prevention when disease is detected early in its natural history thereby allowing intervention, in theory, to improve prognosis.

Screening is a programme not just a test. The test alone cannot achieve any improvement in outcome, so screening comprises a sequence of events. It must be delivered as a well-organised programme of interrelated activities. It encompasses all necessary steps from identifying the eligible population through to delivering interventions and supporting individuals who suffer adverse effects.

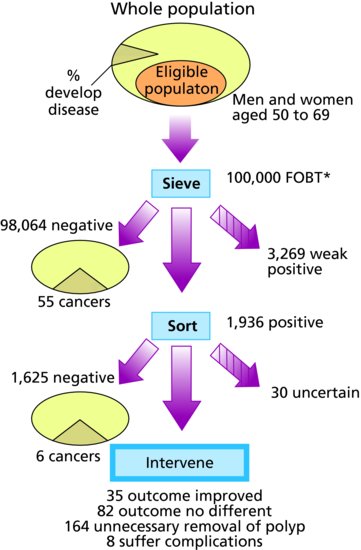

The initial screen is usually followed by further tests for the positives. The screening test is a bit like a sieve that divides a higher risk group and a lower risk group. It does not give certainty. Usually, the people with a positive screening test then need to go on to have more tests. This can be described as the diagnostic phase, or as the ‘sorting’ phase.

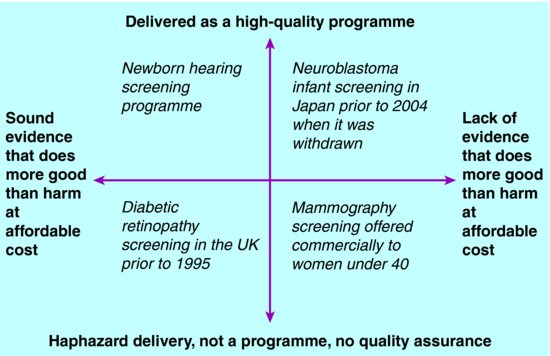

Across the globe there is huge variation in policymaking and delivery. From place to place and over time, examples exist of screening programmes that vary widely in terms of:

- how soundly they are based on evidence;

- how well they are delivered (see Figure 16.1).

What this means is that whilst some screening is evidence-based and high-quality, and leads to more public good than harm at affordable cost, this is not universally the case. Some screening is not based on sound evidence, and some is delivered haphazardly so cannot achieve its potential benefits. This kind of screening does more public harm than good, and is not best value use of resources. It may nevertheless be commercially profitable and highly popular with consumers.

Screening for inherited disorders needs just the same rigour as other screening. Some screening involves testing for inherited or heritable disorders, in people without signs or symptoms and without genetic susceptibility. Such testing can yield information that affects other family members, who did not themselves have a test or give consent to the information being uncovered. Other than this special feature, the same screening principles apply.

What screening does

Screening causes harm as well as benefit. Offering screening to a population leads to diverse consequences. Some individuals may benefit, and some are harmed.

The consequences can be shown using a flowchart. Figure 16.2 shows the screening process and the main outcomes, using bowel cancer as an illustration. Those helped are the people who are identified as cases, receive intervention and have longer life expectancy as a result. Those with an adverse or equivocal outcome are those who have intervention for a condition that would not have become manifest during their natural lifespan, those who suffer complications, those with false alarms, and those who are falsely reassured,

Figure 16.2 The numbers in the flow diagram for bowel cancer screening (Information used in 1998 for planning the UK bowel screening pilots).

*FOBT – faecal occult blood test screen for bowel cancer.

Source: AE Raffle and JAM Gray (2007) Screening Evidence and Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Overdetection is a major downside of many screening programmes yet it is invisible to the public. Many people believe the main harm of screening is the anxiety it causes, although participants tend to say that this is a price worth paying given the benefits. Of greater concern in public health terms is the over-diagnosis and over-treatment inherent in many screening programmes. Breast screening for example leads to some women having breast removal, radiotherapy and chemotherapy for tissue change that would never have caused a problem. It is of course impossible to distinguish the woman who has had life-saving treatment, from the woman who has had unnecessary treatment. This means that paradoxically the popularity of the programme is enhanced by over diagnosis because everyone who is treated tends to the belief that for them it has been life saving.

Screening may change the perception of disease. Once it is suggested that a disease could be screened for, this tends to create an impression that every case could be prevented if only ‘more was done’. This can alter the experience for patients and relatives, who may find it harder to accept the condition and may feel convinced that if somebody had found it sooner then the illness could have been avoided. For this reason it is important to explain screening as a means of reducing risk, rather than a means of ‘prevention’. To the lay public prevention tends to mean total prevention.

Why controlled trials are necessary

Health outcomes in observational studies are likely to be very good even if screening makes no difference. If all you do is measure health outcomes in screened individuals then you will quickly become convinced that screening reduces risk for all kinds of conditions. This is because of three key biases. To control for these biases we need well conducted randomised controlled trials. The three key biases are:

- healthy screenee effect – the people who come for screening tend to be healthier than those who do not, therefore outcome in screened individuals tends to be better than in the background population;

- length time effect – screening is best at picking up long-lasting non-progressive or slowly-progressive pathological conditions, and tends to miss the poor prognosis rapidly-progressing cases; outcome is therefore automatically better in screen-detected cases compared with clinically detected cases even if screening makes no difference to outcome;

- lead time effect – survival time for people with screen-detected disease appears longer because you start the clock sooner.

Neuroblastoma screening provides a case study of why controlled trials of screening are important. Marketing and promotion in the 1980s of screening for neuroblastoma, an infant tumour, prompted a review of evidence by a panel of experts who met in Chicago. Despite the fact that observational studies showed excellent survival in screen-detected cases the experts concluded that these cases could in fact be biologically different from the serious cases that the screening was aiming to help. The panel recommended no adoption of screening, and that randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were needed. Two major RCTs were then conducted. These revealed that deaths were higher in screened infants than in controls, because of overtreatment and consequent deaths from the complications of treatment. Once this evidence was clear, then Japan, which had pioneered neuroblastoma screening, ceased their national programme.

Test performance is important, and there is always a trade-off between finding as many cases as possible, and avoiding too many false alarms and overtreatment. In screening, as with other kinds of testing, it is crucial to define what you mean by a ‘case’ and to assess how well the test or tests can separate cases from noncases. The standard measures of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and likelihood ratios are used (see Chapter 9). The choice of cut-offs for defining what constitutes a positive result is a balancing act between avoiding too many missed cases (sensitivity) versus avoiding too many false alarms (specificity) and the potential for overtreatment. Inevitably, the case-definition for what is being found through screening, for example aortic aneurysm greater than 5.5 cms, is not synonymous with the condition you are hoping to avert, that is, an aneurysm that will fatally rupture. This is why overtreatment happens even though the cases are ‘true positives’.

Advice to provide a good service to patients

Make sure you know how to find key information. Up to date details of the national screening programmes in the UK are all available online and they are constantly changing as quality improves and new evidence emerges. The different kinds of screening are:

- antenatal and newborn – which are linked because staff caring for newborn babies are often key to taking actions that flow from the results of antenatal findings;

- childhood – for example vision screening, growth screening;

- adult – for example abdominal aortic aneurysm screening, bowel cancer screening, diabetic retinopathy screening.

Be clear on the basics. When helping a patient who is deciding whether to be screened make sure you know:

- what exactly is the programme aiming to reduce the risk of?

- who is eligible?

- what does the screen (sieving phase) involve?

- what does the sort involve in terms of further tests?

- what is the intervention?

Develop your skills in helping patients choose in accordance with their values. Your job is to help your patient to understand the good and the bad about screening, to help them weigh up what matters to them, and to support them through the process if they choose to be screened. You also need to respect their decision if they choose not to be screened.

Keep your knowledge up to date. If your job involves being responsible for delivering any part of a screening service then make sure you find out what training is available, and that you keep up to date and follow any quality checks and failsafe procedures.

Be aware that information in the mass media may not be balanced. Information that your patients receive via newspapers, magazines and direct mailed adverts, may be slanted towards ‘selling’ screening. ‘News stories’ are often little more than adverts, having come directly from public relations experts working for companies providing screening. Often journalists will have received payment or favours to encourage them to write positively about private screening clinics. You need to help your patients to make sense of this information. They may be unaware of the commercial motivation for offering screening. They may not realise they are only being offered a test and not a proper programme, and that evidence may be lacking.

Regulation of the content of screening advertising is being developed. Concerns have been raised by the British Medical Association and by the Royal Colleges about the need to protect consumers from highly misleading advertising claims about screening. When selling a mortgage, or stocks and shares, the seller is legally bound to explain the risks for example of house repossession, or that shares can lose value. In stark contrast to this, when selling health screening, there is free reign to use all the skilful techniques of advertising, to play on fears, to keep silent on hazards and lack of proven benefit, to imply that this is a ‘once-only offer’, and to quote testimonials from fictitious grateful customers, carefully chosen to appeal to those most likely to be influenced — ‘thank you from me, my husband, and my golden retriever’. The BMA Board of Science is pushing for changes that will ensure consumers have a right to know:

- all the consequences based on the best available evidence, not just from the test but also from subsequent steps;

- that any benefit can only come about if the test is part of a high-quality programme, and how any other steps in the programme will be provided;

- the financial gain for the person offering the test;

- exactly what they will be charged and what this does and does not cover;

- the desirability of seeking independent advice from a qualified medical practitioner who has no financial interest in the matter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree