Sarcoidosis Lymphadenopathy

Definition

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of worldwide distribution and unknown cause.

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis occurs worldwide, affecting persons of all races and ages. A seasonal clustering prevails, with more cases occurring during winter and early spring (1). Adults between 20 and 40 years of age are usually affected. Sarcoidosis occurs twice as frequently in women as in men, 10 times more frequently in African Americans than in Caucasians, and only very rarely in children (2,3,4). In the United States, the incidence is approximately five cases per 100,000 in the Caucasian population and 40 cases per 100,000 in the African American population (5), with the highest incidence occurring in the southern states. The lifetime risk of developing sarcoidosis is particularly high among Northern Europeans (Swedish women, 1.6%) and African Americans (2.4%) (6). A worldwide survey comparing 3,676 patients in nine different countries showed similar pathologic lesions and clinical presentations (3,4). However a number of studies indicate that sarcoidosis affects those of African ancestry more acutely and more severely than people of other races (7,8,9).

Etiology

The cause of sarcoidosis is still unknown because clinical manifestations overlap with other diseases and specific diagnostic tests are not available (10). Community outbreaks and clustering of cases suggestive of an infectious etiology have been often reported. Supporting this hypothesis are cases in which sarcoidosis was inadvertently transmitted by cardiac and bone marrow transplantation (11,12). Of a variety of infectious agents, mycobacteria have been considered most likely to be involved in the etiology of sarcoidosis. Since its original description a century ago, sarcoidosis has been considered to be related to tuberculosis based on clinical and pathologic similarities (13). Indeed, the granulomatous lesions characteristic of sarcoidosis resemble to a great extent those produced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. leprae. The theory that a mycobacterium is also the cause of sarcoidosis was substantiated by the detection of mycobacterial DNA and rRNA in the affected tissues with the use of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (14,15). The mycobacteria involved in the origin of sarcoidosis may be nontuberculous forms, cell-wall deficient forms, or L forms of mycobacteria, which may explain the repeated failures to stain, culture, or otherwise identify the pathogenic agent of sarcoidosis (13,16). Granulomas induced by beryllium and other dusts or particulate substances also closely resemble those of sarcoidosis, which gave rise to the hypothesis that noninfectious environmental agents, triggering by repeated exposure and exaggerated immune responses, may cause the disease (13). However, although the granulomatous lesions may be indistinguishable, berylliosis only induces localized lesions, unlike sarcoidosis, which is a multiorgan systemic disease.

Pathogenesis

Genetic factors have a part in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis although a single gene does not seem to be responsible (10). A genetic predisposition of the immune response to initiate an exaggerated response to particular antigens appears to be at work. Serologic studies have identified primary associations with major histocompatibility loci such as class 1 HLA-A1 and B8, similar to those found in some autoimmune disorders (5,17).

Essentially all organs may be involved by sarcoidosis, and more than one organ is involved at a given time. The most common sites, in decreasing order of frequency, are the pulmonary hilar lymph nodes, lung, peripheral lymph nodes, liver, eyes, skin, bones, salivary glands, and other organs (18). Although the thoracic lymphadenopathies overshadow the pulmonary lesions (which sometimes are inapparent), recent studies have shown that in most cases sarcoidosis begins with an initial focus of alveolitis (5). Subsequently, the process evolves, with the development of characteristic granulomas followed by fibrosis. Cardiac sarcoidosis is the most common cause of death in sarcoidosis, because of the fibrosis that it produces (19). Underlying these lesions are severe alterations of immune mechanisms manifested both at the site of involvement and systemically. The disorder is not a state of generalized anergy and is not associated with increased incidence of cancer, as was previously believed, but produces a state of greatly increased cellular activity in the organs involved. The amount of CD4+ T cells is decreased in the peripheral blood of patients with sarcoidosis, whereas in the tissues involved, the CD4-to-CD8 T-cell ratio is increased, indicating a state of cell-mediated hyperreactivity (20,21,22). A subset of CD4+ lymphocytes lacking CD28 (an important costimulatory molecule) is increased in some inflammatory conditions. Higher proportions of such C4+/CD28- lymphocytes have been found in the peripheral blood and lungs of patients with sarcoidosis (23). Alterations of CD8 T-cell inhibitory receptors have also been reported (24). In addition to the accumulations of T cells and monocytes, numerous B cells and plasma cells are present, indicating the production of immunoglobulins at the sites of granuloma formation (20,25). Hypergammaglobulinemia as a result of uncontrolled B-cell activation and circulating immune complexes are also common findings in sarcoidosis (3). Circulating monocytes are attracted to the areas of granuloma formation, where they are transformed into epithelioid and giant cells (26,27,28). The epithelioid cells and circulating monocytes synthesize angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), a glycoprotein component of the renin-angiotensin system, and lysozyme; both are present in increased amounts in serum and in tissues involved by granulomas (29). Hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, which may be prominent features of sarcoidosis, are related to increased

plasma levels of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, or calcitriol, which is also produced by the epithelioid cells of sarcoid granulomas (30). Thus, a chronic cascade of inflammatory processes occurs in which unknown antigens drive a hyperactive cellular immune response, with T cells producing interferon-γ and interleukin-2, and the epithelioid cells releasing a variety of cytokines, chemoattractants, and a variety of other proinflammatory mediators (5,10,31).

plasma levels of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D, or calcitriol, which is also produced by the epithelioid cells of sarcoid granulomas (30). Thus, a chronic cascade of inflammatory processes occurs in which unknown antigens drive a hyperactive cellular immune response, with T cells producing interferon-γ and interleukin-2, and the epithelioid cells releasing a variety of cytokines, chemoattractants, and a variety of other proinflammatory mediators (5,10,31).

Clinical Syndrome

Sarcoidosis may involve multiple organs and present with a wide variety of symptoms: an acute onset of symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and erythema nodosum, which is associated with good prognosis, or a chronic course including pulmonary, pericardial, or myocardial involvement, which indicates an unfavorable prognosis (5). Cardiac involvement is more common than previously thought, although it is difficult to diagnose clinically and may be the cause of arrhythmias and sudden death in 5% to 10% of patients with sarcoidosis (19). The disease is more severe and more persistent in those of African descent and in the elderly. In most cases, however, sarcoidosis remits spontaneously, with complete cure. Because sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease various patterns of presentation are possible; however, the most common lesions are respiratory, ocular, and dermatologic (4). In the United States, more than half of patients present with chronic respiratory symptoms and few general signs (10).

Lymphadenopathies are frequently present in cases of sarcoidosis, and the pulmonary hilar lymph nodes are most commonly affected (77% of cases) (32). Involvement of peribronchial lymph nodes, bilateral and symmetric, in the absence of peripheral or mediastinal lymphadenopathy and with little or no pulmonary infiltrates, is almost pathognomonic for sarcoidosis (33). Granulomatous uveitis, usually bilateral, occurs in 15% of patients (6). Iritis, sinusitis, erythema nodosum, and bone and joint lesions may also appear as manifestations of sarcoidosis, singly or in association with the pulmonary and lymph node lesions. Parotid gland sarcoidosis occurs in 6% of patients with sarcoidosis, bilaterally in two-thirds of cases (34). Sjögren syndrome, another autoimmune disease, may often coexist with sarcoidosis (35). Frequent accompanying findings are elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated level of ACE, reversal of the albumin-globulin ratio, hypergammaglobulinemia, hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, and abnormal liver function tests (36). Biopsies of the gums, nose, lung, or lymph nodes demonstrating the characteristic sarcoid granulomas and a positive Kveim test are diagnostic procedures that positively identify sarcoidosis.

The common procedure of bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsy is nondiagnostic in 30% of patients with suspected sarcoidosis and has the risk of pneumothorax and hemoptysis. A preferable approach is biopsy of mediastinal lymph nodes, through the esophagus, using endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) (37).

Spontaneous recovery is common. In one study, mediastinal adenopathy cleared at the end of 5 years in 82% of Swedish patients and in another study in 85% of white and 65% of black patients after 9 years. The most reliable indication of favorable outcome is the onset with erythema nodosum. Serious disabilities from various causes occur in 10% of patients, and mortality in sarcoidosis is below 3% (6).

Recently, cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis associated with interferon-α therapy for some tumors, but primarily for chronic hepatitis C, were reported (38,39). The clinical courses, radiographic images, and histopathology were typical for sarcoidosis; however, the characteristically associated mediastinal lymphadenopathies were not apparent in any of the reported cases.

Histopathology

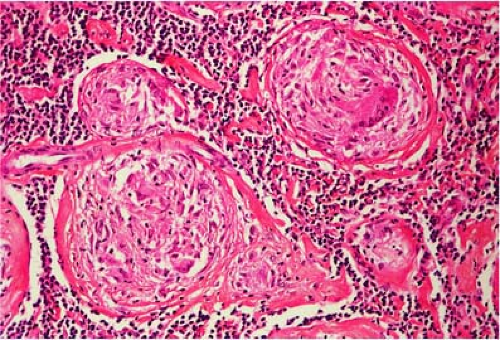

The noncaseating granuloma is the characteristic histologic feature of sarcoidosis in all tissues. In the involved lymph nodes, the architecture is partially or totally replaced by numerous, closely packed, well-demarcated granulomas (Figs. 38.1,38.2,38.3 and 38.4) (40). Occasionally, the granulomas are less well demarcated (Fig. 38.3) and may even coalesce (Fig. 38.5). They are composed predominantly of epithelioid cells (Figs. 38.2 and 38.4) with scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figs. 38.2, 38.4, 38.6, and 38.7), lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibroblasts. CD4+, CD8+ T lymphocytes and, to a lesser extent, B lymphocytes form a concentric rim around the epithelioid granuloma. The ratio of CD4+ T-helper cells to CD8+ T-suppressor cells is markedly increased in the granulomas but not in the peripheral blood. Early in the formation of granulomas, no surrounding lymphocytes may be present, resulting in naked granulomas (41) (Figs. 38.3 and 38.4). The epithelioid cells are arranged in

concentric rows, forming “perimeters of defense” against antigens presumed to be in the central areas of granulomas (Fig. 38.6) (23,24,25).

concentric rows, forming “perimeters of defense” against antigens presumed to be in the central areas of granulomas (Fig. 38.6) (23,24,25).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree