Roux-En-Y Lateral Pancreaticojejunostomy for Chronic Pancreatitis

Charles J. Yeo

Eugene P. Kennedy

Chronic pancreatitis is a single term applied to a complex spectrum of disease. The essence of this disease process is the progressive destruction of the pancreatic parenchyma and its replacement with fibrotic tissue. This occurs through a poorly understood chronic inflammatory process. Over time, this leads to both exocrine and endocrine insufficiency.

Chronic pancreatitis is such a varied disease process due to the wide range of conditions that can trigger this destructive inflammatory process. The most common etiology is chronic excessive ethanol consumption. Along with other toxic or metabolic causes such as hypercalcemia, hyperlipidemia, certain medications, and perhaps tobacco, it is postulated that these factors first create an environment of acute pancreatitis that progresses as a result of continued exposure to a chronic inflammatory state. The end result is periacinar fibrosis, collagen deposition, and glandular dysfunction. Other well-described etiologic factors for chronic pancreatitis include hereditary pancreatitis (including mutations in the cationic trypsinogen (PRSS1), pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor (SPINK1), and chymotrypsinogen C (CTRC) genes), cystic fibrosis, autoimmune disease, prior severe acute pancreatitis with necrosis, pancreatic ductal obstruction from developmental abnormalities (pancreas divisum), sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, or obstruction from trauma or neoplasm. Patients not fitting one of these diagnostic categories are classified as idiopathic, a group that ranks second to ethanol consumption when etiologies are tallied.

Just as the etiology of chronic pancreatitis is widely varied, so is the clinical presentation and disease course experienced by patients. Although progressive organ dysfunction is characteristic of the disease, the hallmark symptom is chronic, often disabling pain. The pain is classically located in the epigastric region and presents as a dull ache that radiates to the back. The exact nature of the pain and the timing of its occurrence in relationship to other aspects of the disease can vary greatly between patients. Some patients experience intermittent pain that can last days and be disabling. Fatty foods are often cited as a trigger, but the pain can frequently arise without any obvious trigger. Between episodes, these patients can be symptom-free, but the severity, duration, and frequency of episodes often increase over time in a crescendo pattern. Other patients experience a more chronic, daily form of pain with intermittent exacerbations. The onset of episodes of chronic pain can vary greatly between patients, with certain patients experiencing pain early in the course of chronic pancreatitis, whereas other uncommon patients can exhibit endocrine and exocrine insufficiency and dramatic radiographic evidence of chronic pancreatitis without any significant pain episodes.

The pain associated with chronic pancreatitis is typically the most disabling feature of the disease and the symptom that drives patients to seek frequent medical attention. Because the pain typically increases over time, patients may become habituated to narcotic pain medications and often require episodic inpatient care. The pain and the side effects of pain medications dramatically impair quality of life and often result in disability and loss of employment. Ultimately, failures of medical approaches to pain management lead patients to surgical intervention for their conditions.

The etiology of the pain that results from chronic pancreatitis is unclear. Historically, it was thought to be due to the strictures that classically arise in the main pancreatic duct from the chronic inflammatory process. It was thought that these strictures resulted in increased pressure within the pancreatic duct, which in turn resulted in the sensation of pain. This concept was seemingly supported by the observation that surgical procedures designed to drain the pancreatic duct could result in decreased pain. However, more recent investigations have demonstrated the pain associated with chronic pancreatitis to be multi-factorial.

Studies performed over the past 25 years have illuminated the complex nature of chronic pancreatitis-associated pain. Multiple studies evaluating pancreatic duct size and pressure measurements have failed to consistently demonstrate a direct relationship between duct abnormalities and pain scores. Additionally, significant numbers of chronic pancreatitis patients have essentially normal size pancreatic ducts (so-called “small-duct” or “minimal-change” chronic pancreatitis) but have significant pain, even early in the course of their disease. Furthermore, studies evaluating total pancreatectomy with islet cell auto-transplant have shown that even this dramatic procedure fails to relieve pain in all patients, implying that more than simple mechanical mechanisms are at work in chronic pancreatitis.

More recently, the pain associated with chronic pancreatitis has been attributed, in part, to a neuropathic sensitization of the peripheral and central sensory pathways. This sensitization is driven directly by the chronic inflammatory process ongoing in chronic pancreatitis as well as by chemical and neurotransmitter-mediated stimulation. Microscopic evaluation of pancreas nerves has shown evidence of neural injury in the setting of chronic pancreatitis. Factors present in the pancreatitis milieu, including trypsin and capsaicin, can cause activation and hypersensitivity of sensory pancreatic neurons in experimental models. Additionally, studies have shown that cholecystokinin (CCK) can be significantly elevated in blood of some chronic pancreatitis patients. CCK can act directly on the central nervous system via receptors in the area postrema of the medulla. From here, neuronal pathways connect to central pain centers and areas responsible for the emotional response to pain, providing a plausible mechanism for a role for CCK in the pain associated with chronic pancreatitis. One preliminary randomized trial of an oral CCK receptor antagonist demonstrated decreased pain scores for patients on the treatment arm of the trial.

In addition to chronic pain, patients with chronic pancreatitis often present with a combination of other symptoms related to the exocrine and endocrine insufficiency that results from destruction of the gland. Steatorrhea, malabsorption, fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, malnutrition, and weight loss are all common. Diabetes may result from impaired islet cell function.

Associated medical problems from long-term ethanol abuse as well as side effects from narcotic pain medications are also common.

Associated medical problems from long-term ethanol abuse as well as side effects from narcotic pain medications are also common.

The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is made via a combination of patient history, the constellation of symptoms, and radiographic findings. Evaluation typically is prompted by a complaint of chronic abdominal pain. Patient history may reveal ethanol use, prior episodes of acute pancreatitis, a suspect drug, or a family history or known genetic predisposition. Laboratory evaluation is often uninformative as patients with chronic pancreatitis can have severe exacerbations with normal serum amylase and lipase levels. Causes such as hyperlipidemia and hypercalcemia can be detected, but these are rare. Hyperglycemia and malabsorption are typically late findings once the disease has progressed over time.

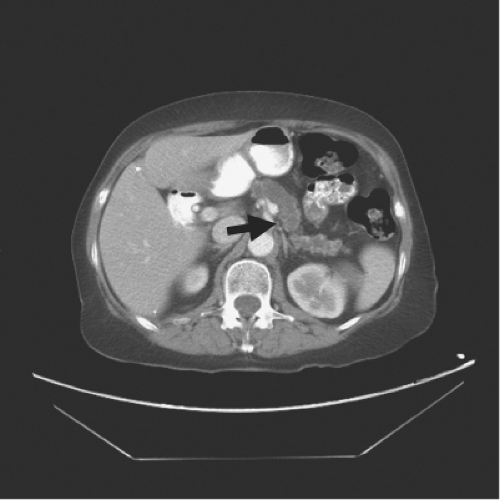

Imaging is a key element in diagnosis. Classically, patients with chronic pancreatitis have dilatation of the pancreatic duct, which can be detected on imaging. A “chain of lakes” is often seen from segmental strictures due to the inflammatory process. Calcifications in the pancreatic parenchyma are essentially pathognomonic. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has traditionally been the standard imaging technique used to evaluate the pancreatic duct and make a diagnosis. However, it is associated with a significant risk of complications, including exacerbation of the pancreatitis. Therefore, the initial imaging study of choice to evaluate the possible diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is a high quality, multi-detector, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1). CT is quite accurate for detecting dilatation of the pancreatic duct as well as parenchymal calcifications. With proper contrast enhancement, it also gives an excellent assessment of the pancreatic parenchyma and surrounding vasculature.

When greater resolution of the pancreatic duct is necessary, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) provides excellent imaging of the pancreatic duct. Utilizing T2 weighted images, the detailed structure of the pancreatic duct can be seen with high resolution. In our practice, we strongly prefer MRCP over ERCP as a diagnostic imaging study. However, endoscopy may provide complementary data via endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). Though not required for most cases, EUS can help evaluate the parenchyma of the pancreas in fine detail, particularly when trying to discern an inflammatory stricture or mass from a subtle neoplasm. Additionally, EUS offers the additional advantage of tissue retrieval via fine needle aspiration when a diagnosis is uncertain from imaging alone.

The treatment of chronic pancreatitis is truly multi-modal and requires cooperation between specialties. Once a diagnosis is done, every effort should be made to identify the etiology of the pancreatitis. If the chronic pancreatitis is due to ethanol abuse, then aggressive steps should be made to assist the patient in ethanol cessation. Simply stopping the consumption of ethanol can lead to improvements in symptoms and decrease the rate of progression of the disease. Similar efforts should be applied toward smoking cessation for the patients who abuse tobacco. Metabolic abnormalities that trigger pancreatitis should be treated and any possibly related drugs stopped or changed.

Once triggering factors are removed, treatment focuses on symptom relief. Pain is managed with analgesics and often requires significant doses of narcotics. Collaboration with a chronic pain specialist and careful monitoring of narcotic prescriptions and dosing can help differentiate appropriate management from signs of abuse. Exocrine and endocrine insufficiencies are managed with pancreatic enzyme replacement and insulin therapy, respectively. Nutritional support is also initiated when appropriate.

The most common indication to intervene surgically in chronic pancreatitis is unremitting pain that significantly interferes with quality of life and cannot be adequately addressed medically. Evidence exists that surgical interventions for chronic pancreatitis can slow the progression of the disease and delay the loss of pancreatic function. However, this in and of itself is not an adequate indication for surgical intervention. Traditionally, it was taught that chronic pancreatitis would “burn itself out” and if surgical intervention was delayed long enough, symptoms would improve. However, this theory has not held up to scientific scrutiny, and patients randomized between medical and surgical interventions had significantly less pain over the ensuing 10 years of follow-up if they had undergone surgery. Additionally, a recent randomized study comparing endoscopic and surgical interventions for chronic pancreatitis was stopped early due to clear superiority at interim analysis in the surgical arm.

Surgical interventions for chronic pancreatitis can be divided into two broad groups: drainage operations and resectional operations. The evolution of surgery for chronic pancreatitis can be traced to 1911 when Link performed the first successful drainage procedure for chronic pancreatitis due to proximal obstruction of the pancreatic duct. His tube pancreatostomy provided

many years of symptomatic relief for his patients and established drainage of the duct as a valid approach. In 1954, Duval described using distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy with an end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy between the cut end of the body or tail of the pancreas and a Roux-en-Y limb of jejunum to decompress the pancreatic duct. The efficacy of this procedure was limited, however, by recurrent or progressive segmental strictures along the length of the pancreatic duct, described as a “chain of lakes” by Puestow and Gillesby. They modified Duval’s procedure by making a longitudinal opening along the main pancreatic duct through the tail and body of the pancreas and then invaginating the distal gland into a Roux-en-Y limb of jejunum. In several of their reported cases, they alternately performed a side-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy for drainage. In 1960, Partington and Rochelle described the side-to-side longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy that is currently referred to as the Puestow procedure. This procedure remains a standard approach to pancreatic ductal decompression. It is best applied to patients with parenchymal disease and pancreatic ductal dilatation diffusely involving the pancreatic head, neck, body, and tail of the gland. It requires a significant degree of pancreatic ductal dilatation to be technically feasible with a ductal diameter of at least 5 mm.

many years of symptomatic relief for his patients and established drainage of the duct as a valid approach. In 1954, Duval described using distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy with an end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy between the cut end of the body or tail of the pancreas and a Roux-en-Y limb of jejunum to decompress the pancreatic duct. The efficacy of this procedure was limited, however, by recurrent or progressive segmental strictures along the length of the pancreatic duct, described as a “chain of lakes” by Puestow and Gillesby. They modified Duval’s procedure by making a longitudinal opening along the main pancreatic duct through the tail and body of the pancreas and then invaginating the distal gland into a Roux-en-Y limb of jejunum. In several of their reported cases, they alternately performed a side-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy for drainage. In 1960, Partington and Rochelle described the side-to-side longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy that is currently referred to as the Puestow procedure. This procedure remains a standard approach to pancreatic ductal decompression. It is best applied to patients with parenchymal disease and pancreatic ductal dilatation diffusely involving the pancreatic head, neck, body, and tail of the gland. It requires a significant degree of pancreatic ductal dilatation to be technically feasible with a ductal diameter of at least 5 mm.

Resectional intervention is best applied to parenchymal disease and pancreatic ductal abnormality that is primarily confined to one portion of the pancreas. The same resectional approaches used for neoplasms (pancreaticoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy) as well as total pancreatectomy with islet cell auto-transplant are utilized at some centers. When properly applied, these approaches yield acceptable results.

There are also two additional approaches developed more recently that combine the aspects of both resectional and drainage approaches. First, the duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection or Beger procedure addresses the problem of an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas. The pancreatic head is resected while preserving the blood supply to the duodenum and distal bile duct. Two pancreatic anastomoses are performed (to the proximal remnant attached to the duodenum as well as to the distal pancreas), and the distal anastomosis can be modified to incorporate a longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy if the ductal anatomy indicates that such an addition would better decompress the left-sided ductal system. Second, the local resection of the pancreatic head with longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy or Frey procedure seeks to address the problem that occurs in patients with significant disease in the pancreatic head as well as a “chain of lakes” along the pancreatic duct throughout the body and tail. The ventral aspect of the pancreatic head is resected along with the ducts of Wirsung and Santorini, leaving a cavity in the pancreatic head. A lateral pancreaticojejunostomy is then sewn in continuity with the cavity in the head of the gland, decompressing the entire organ in a single anastomosis. Both procedures compare favorably with the traditional Puestow procedure, but are more technically challenging to perform.

Preoperative planning for a Roux-en-Y longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy begins with appropriate patient selection. As mentioned, it is best applied to patients with parenchymal disease and ductal dilatation diffusely involving the pancreatic head (medial to the gastroduodenal artery), neck, body, and tail of the gland. The degree and distribution of ductal dilatation noted on preoperative imaging is the key to patient selection. Although there have been reports of success with lateral pancreaticojejunostomy in patients with small duct disease, classically this procedure had been reserved for those patients with a pancreatic duct that measured at least 1 cm in diameter. More recently, increasing experience with this procedure has decreased the lower limit of duct dilatation that most pancreatic surgeons are comfortable with to the 5 mm range.

In addition to evaluation of pancreatic ductal anatomy, the overall condition of the patient must be assessed prior to operative intervention. A patient’s symptoms must be severe enough and disabling enough to justify surgical intervention. Surgical intervention via lateral pancreaticojejunostomy for chronic pancreatitis has essentially one goal, relief of pain. Patients with other sequelae of chronic pancreatitis such as biliary or duodenal obstruction or pseudocyst formation are best served with a different approach. As relief of pain is the primary goal, alcohol and tobacco cessation are a must. In our practice, it is our policy to not offer a surgical intervention for pain to the patients who continue to abuse ethanol or to those who smoke cigarettes. Nutritional parameters must be assessed. Patients demonstrating significant malnutrition (with serum albumin levels less than 3 g/dL) require nutritional supplementation prior to operative intervention. Other medical conditions such has cardiac disease must be assessed and optimized prior to surgery as well.

All patients are admitted as same-day surgery patients, having been previously seen in the anesthesia preoperative evaluation clinic. No preoperative bowel preparation is utilized and patients are simply instructed to limit intake to clear liquids from noon onward the day before surgery. Necessary cardiac medications including beta-blockers and aspirin are continued. Anticoagulants such as warfarin and enoxaparin are held, however, as is clopidogrel. Patients receive 5000 units of heparin subcutaneously in the preoperative holding area and a second generation cephalosporin (or appropriate equivalent if allergic) is administered in the operating room less than 30 minutes prior to incision. Sequential compression devices (SCDs) are utilized. A nasogastric tube and a urinary catheter are placed after the induction of anesthesia. Central venous access is obtained only when deemed necessary by the attending anesthesiologist. Epidural analgesia is not utilized. A preoperative briefing involving all members of the surgical team is performed prior to incision.

A midline incision from the xiphoid to the umbilicus is used for the procedure. A self-retaining retractor system is used to aid with exposure and wet, antibiotic-soaked laparotomy pads are used to protect the wound edges. A thorough exploration of the abdomen is performed. If a patient has not yet undergone a cholecystectomy, one is performed in the classic, top-down fashion.

Next, the pancreas is approached by opening the gastrocolic ligament, along the greater curve of the stomach up to the first short gastric vessel, thereby entering the lesser sac. The ligament is divided using Kelly clamps and silk ties, careful to avoid the gastroepiploic vessels. The short gastrics are not divided. Any adhesions between the back wall of the stomach and the ventral surface of the pancreas are divided and the entire ventral surface of the pancreas is exposed. Typically, there is no need to perform a Kocher maneuver to safely complete the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree