30

Risk: What Is It? Risk Management and Assessment, Risk Evaluation and Minimization Systems (REMS), and Risk Management Plans (RMPs)

Risk is a broad concept and applies to everything in life. We take risks when we drive a car, go to work, eat a meal, and take a drug. Risk analysis of drugs is now very much in vogue to aid the patient and healthcare professional, as well as the health authorities and drug companies, in decision-making. This chapter looks at risk first in a global manner and then as applied to drug therapy in the United States with Risk Management Minimization Systems (REMSs), and in the European Union with Risk Management Plans (RMPs). We are all working on the presumption that these new risk management systems and plans will decrease risk. This, in fact, remains to be seen. Most of the plans require some measure of outcomes and determination of whether risks and suffering have decreased. How this will play out remains to be seen.

Risk can be defined in many ways:

- Exposure to a possibility of loss or damage

- The quantitative or qualitative possibility of loss that considers both the probability that something will cause harm and the consequences of that something

- The probability of an adverse event’s resulting from the use of a drug in the dose and manner prescribed or labeled, or from its use at a different dose or manner or in a patient or population for which the drug is not approved

- The exposure to loss of money as a result of changes in business conditions, the economy, the stock and bond markets, interest rates, foreign currency exchange rates, inflation, natural disasters, and war

Over the past 10 years or so, many in the pharmaceutical world (as elsewhere) have been thinking about risk assessment and management. Several documents on risk management have been produced by various groups. Early documents included U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) draft guidances in 2003, ICH E2E (Web Resource 30-1), finalized in 2005, and a European Medicines Agency (EMA) risk management guidance also in 2005. Risk management during the life cycle of products is now the norm and is expected by FDA, EMA, and other agencies.

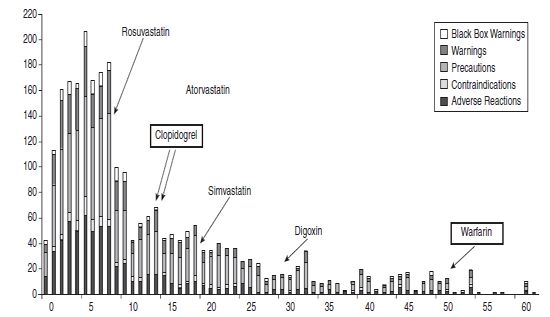

Figure 30.1Composition of Safety-Related Labeling Changes for All Drug Products

Years post-approval

(changes made Oct 2002-Aug 2005, n=2645 label changes for 1601 NDA/BLA entries)

Source: Modified from T Mullin, CDER, Office of Planning and Analysis, OTS presentation, May 2009 (http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/DrugInteractionsLabeling/UCM205986.pdf).

The FDA has looked back on labeling changes in the United States over several years and a striking finding is that safety label changes occur years and even decades after a drug has been approved as new safety issues are reported. For example, changes can occur at 50 or 60 years after approval even for such a commonly used and “well-known” drug as warfarin. Figure 30.1 from the FDA illustrates label changes occurring after drug approval.

Why Risk Management?

Why Risk Management?

When a drug first reaches the market, its safety profile is not well characterized. Relatively few patients have been studied (especially with orphan drugs), and those who have been studied are usually patients with no other diseases, no or few comedications, not too young or old, with tight inclusion and exclusion criteria in the clinical trials. Thus, “real-world” patients have not taken the drug yet, and rare adverse drug reactions (ADRs) have not been detected. It is only in the postmarketing arena, when large numbers of patients have taken the drug, that the safety profile is better characterized. It is only when data on compliance, use in patients with comorbid conditions, and multiple other drugs (including over-the-counter) and diets are examined that the real-world safety profile develops. In addition, data from overdose, suicide attempts, unintended pregnancies, and lactation will add to the profile.

Until recently, the primary way to collect such data was from spontaneous reporting systems and periodic aggregate reports (PADERs, Periodic Safety Update Reports, or PSURs, and their various predecessors) and occasional postmarketing studies. Risk management in a formal sense was not done.

Multiple drivers have come into play in pharmacovigilance and risk management:

- Multiple major safety issues and withdrawals occurred: Fen-Phen, Propulsid, Rezulin, Vioxx, Bextra, Tysabri, Zelnorm, and others.

- Rising liability costs from litigation and settlements.

- The medical community was not happy with drug marketing and drug information.

- ADRs were perceived to be a major health risk, producing death, hospitalization, and significant morbidity. A meta-analysis noted that in 1994 more than 2 million hospitalized patients had serious ADRs and more than 100,000 died, making this the fourth or fifth leading cause of death in the United States (Lazarou, Pomeranz, Corey, Incidence of ADRs in hospitalized patients. JAMA 1998;279:1200–1205). Other publications from around the world noted similar findings.

- A public and media perception that drug companies were villainous, greedy, and cared little for public health.

- The internet, bloggers, social media, and other forums’ circulating stories, correct or not, on the harm of drugs.

- A perception that the regulators were not doing their job by allowing harmful drugs to reach the market too quickly.

- A perception that the agencies and industry were too closely aligned.

- Media stories highlighting gifts to physicians, slanted continuing medical education, paid speakers bureaus, and multiple conflicts of interest.

- In addition, recent economic issues have brought risk management of money, cars, offshore oil wells, pharmaceuticals, and many other activities in daily life into everyone’s mind. One result has been that much of the world has become risk-averse (at least for now).

A consensus developed that risk prediction, evaluation, management, and minimization were not well understood and were rarely done and, when done, were done poorly. Better procedures for risk identification (signaling), characterization, mitigation/minimization, tracking, and communication were needed. And this was necessary for the entire life span of the product, not just after marketing. Companies and health agencies (and in some cases other organizations) needed to be proactive, collect more and better data, put it into electronic databases that were able to “talk to each other,” and from which data could easily be extracted for risk evaluation. The benefit–risk analysis (called by the pessimists the risk–benefit analysis) needed to be done in a serious, quantitative, and reproducible manner. It was also understood that the benefit–risk situation will change over the course of a drug and may differ from patient to patient, group to group, indication to indication.

The goals then became:

- Early and better detection of ADRs and characterization of the risk in various patients and settings

- Development and harmonization of data standards and electronic transmission and storage

- Better communication of known and unknown risks

- Minimization of morbidity and mortality—protecting the public health

Many actions on many fronts have occurred already and more are under development. They are summarized below.

The FDA

The FDA

The FDA first published a document on its thinking in May 1999, entitled “Managing the Risks from Medical Product Use and Creating a Risk Management Framework.” It addressed pre- and postmarketing risk management and the FDA’s role. Further publications have extended and elaborated the FDA’s position.

The FDA has published three guidances for industry on risk management (see Chapters 30 and 31):

- Premarketing Risk Assessment (Web Resource 30-2)

- Development and Use of Risk Minimization Action Plans (RiskMAPs) (Web Resource 30-3)

- Good Pharmacovigilance Practices and Pharmacoepidemiologic Assessment (Web Resource 30-4)

The first guidance, on premarketing risk assessment, focuses on measures companies might consider throughout all stages of clinical development of products. For example, a section on special safety considerations describes ways that risk assessment can be tailored for those products intended for use chronically or in children.

General recommended risk assessment strategies include long-term controlled safety studies, enrollment of diversified patient populations, and phase III trials with multiple-dose levels. Some key components of the guidance include:

- Providing specific recommendations to industry for improving the assessment and reporting of safety during drug development trials

- Improving the assessment of important safety issues during registration trials and providing best practices for analyzing and reporting data that are developed as a result of a careful preapproval safety evaluation

- Building on (but not superceding) a number of existing FDA and International Conference on Harmonization guidances related to preapproval safety assessments

The second guidance, on RiskMAPs, describes how industry can address specific risk-related goals and objectives. This guidance also suggests various tools to minimize the risks of drug and biologic products. This guidance has been superseded by a later FDA guidance on REMS (see below). Key components of the guidance include:

- Establishing consistent use and definition of terms and a conceptual framework for setting up specialized systems and processes to ensure product benefits exceed risks

- Broader input from patients, healthcare professionals, and the public when making recommendations about whether to initiate, revise, or end risk minimization interventions

- Evaluating RiskMAPs to ensure that risk minimization efforts are successful

The third guidance, on the postmarketing period, identifies recommended reporting and analytical practices to monitor the safety concerns and risks of medical products in general use. Some key components of this guidance include:

- Describing the role of pharmacovigilance in risk management. Pharmacovigilance refers to all observational postapproval scientific and data-gathering activities relating to the detection, assessment, and understanding of adverse events with the goals of identifying and preventing these events to the extent possible.

- Describing elements of good pharmacovigilance practice, from identifying and describing safety signals, through investigation of signals beyond case review, and interpreting signals in terms of risk.

- Describing development of pharmacovigilance plans to expedite the acquisition of new safety information for products with unusual safety signals.

In September 2007, with the passage of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA), the concept of the RiskMAP was superseded by the new REMS. FDA also produced a major new 5-year plan with multiple new initiatives (see Chapter 21).

The concepts behind this plan were that all products need full life cycle risk management, including older and already marketed products. In addition, some products (both new and old) may need specific REMS above and beyond routine postmarketing surveillance. The REMS must be tailored to the product and its known and unknown risks; it must be able to minimize risk in a measurable, quantifiable way; and it must be modified if the risks are not minimized. In addition, effective communication methods are to play a major role in REMS.

In September 2009, the FDA issued a major guidance entitled “Proposed Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS), REMS Assessments, and Proposed REMS Modifications” (Web Resource 30-5). This important document, which has the REMS template, will be summarized here.

The FDA may require companies submitting New Drug Applications (NDAs), abbreviated New Drug Applications 58 (ANDAs), and biologics license applications (BLAs) to submit a REMS if FDA “determines that such a strategy is necessary to ensure that the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks of the drug.” A company may voluntarily submit a proposed REMS if it believes that a REMS would be necessary to ensure that the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks. Companies that had RiskMAPS in place will continue with them and, in some cases, convert them to REMS with or without changes and additions.

The requirement for a REMS is enforceable by law, and if the person responsible for the drug (in the company) fails to comply, the drug is considered misbranded. Penalties of up to $1 million are possible for the first violation and may increase to $10 million for subsequent violations.

The content of a REMS is described. There are two major sections: (1) a proposed REMS and (2) a REMS supporting document (see the appendix).

The Proposed REMS

The Proposed REMS

- Table of Contents

- Background: The REMS should describe the important risks (e.g., those seen in clinical and preclinical studies), risks seen with similar products or other drugs in the class, and risks expected with the underlying medical problem or disease (e.g., cancer seen with ulcerative colitis). It should also identify subgroups at risk (e.g., certain demographic groups such as the elderly or newborns) and if there are risks seen with similar products (e.g., bleeding with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] or rhabdomyolysis with statins).

- Goals: The goals and objectives of the REMS. The goal is a desired safety-related outcome or understanding by patients and providers. It should be clear and absolute, and aim to achieve maximum risk reduction. It should be pragmatic, specific, and measurable. Examples:

- Patients on Y drug should be aware of the risks of rhabdomyolysis (measurable by the number of serious adverse events, or SAEs, of rhabdomyolysis).

- Patients on X drug should not also be prescribed Y drug (measurable by the number of patients receiving both drugs together).

- Fetal exposures to Z drug should not occur (measurable by the number of fetal exposures).

- Patients on Y drug should be aware of the risks of rhabdomyolysis (measurable by the number of serious adverse events, or SAEs, of rhabdomyolysis).

- REMS Elements: The REMS may have one or more of the following:

- Medication Guide or Patient Package Insert (PPI)—This will be required if patient labeling could prevent SAEs, if the risks relative to the benefits could affect the patient’s decision to use or continue using the drug, or if adherence to directions for use is crucial for effectiveness of the drug.

- Communication Plan to Healthcare Providers—This may be variable and include letters to healthcare providers, and information about REMS elements to encourage implementation or to explain certain safety requirements such as periodic laboratory tests.

- Elements to Assure Safe Use (ETASU)—These will be used if a medication guide and communication plan are not sufficient.

- Prescribers have certain training experience or certification.

- Facilities dispensing the drug are certified.

- Drug is only dispensed to patients in certain settings (e.g., hospitals).

- Drug is dispensed with documentation of safe-use conditions (e.g., laboratory tests).

- Patients are subjected to monitoring.

- Patients enroll in a patient registry.

- Prescribers have certain training experience or certification.

- Implementation System—If included in the REMS, it should describe the system for implementing, monitoring, and evaluating the intended goals and effects.

- Timetable for Assessments—The assessments should be done no less frequently than at 18 months, 3 years, and 7 years after the REMS is approved.

- Medication Guide or Patient Package Insert (PPI)—This will be required if patient labeling could prevent SAEs, if the risks relative to the benefits could affect the patient’s decision to use or continue using the drug, or if adherence to directions for use is crucial for effectiveness of the drug.

- REMS Assessment Plan: What will be done and measured to see whether the goals are achieved and what are the success criteria.

- Other Relevant Information

Appendix: Supporting documents are included for each section above.

Comments

The goals of the REMS are to continually assess the benefit–risk balance and to ensure that it remains positive, if not globally, for all patients treated, than for some subsets. This may not be clear before marketing, but, where a REMS is required, the best effort must be put into designing a logical and thoughtful REMS, realizing it may change with experience gained after marketing.

Careful thought by a team knowledgeable about the disease and drug in question should work on the REMS. They need to evaluate the patients and disease to determine whether there are measurable early signs, symptoms, or markers that will allow a risk management intervention to prevent a bad outcome or SAE. This will require review of the data available for the drug and similar products, and an understanding of how the drug will be used in the “real world” and whether different populations from those in the clinical trials will be exposed to the drug. Obviously, much of this may not be known before marketing, making it necessary to change the REMS after marketing starts. The tricky question of off-label use (if anticipated) should be considered and possibly incorporated in the REMS.

Some specific examples of ETASUs:

- Prescribers have certain training experience or certification:

The healthcare professional may be required to have particular training or skills to diagnose the condition being treated, understands the risks and benefits, and to have read the materials provided in the REMS and has particular skills and training to diagnose and treat particular ADRs associated with the product. Training may be by mail or online and should not be too costly to the provider.

- Facilities dispensing the drug are certified:

This refers to pharmacies, practitioners, or healthcare facilities that may be required to understand the risks and benefits and to have read the materials provided in the REMS, to agree to dispense the drug only after receiving prior authorization, to agree to check lab values or to check for the presence of stickers that providers affix to prescriptions to indicate that the patient has met all criteria for receiving the product (“qualification stickers”), to agree to fill the prescription only within a specified period of time after the prescription is written, and to agree to fill prescriptions only from enrolled prescribers.

- Drug is only dispensed to patients in certain settings:

Settings may include hospitals or physicians’ offices equipped to handle specific ADRs, such as allergic reactions or cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

- Drug is dispensed with documentation of safe-use conditions:

This may refer to checking laboratory tests (e.g., for pregnancy, white blood cell count), receipt of educational materials and demonstration that the patient has understood the risks and benefits, verification by the pharmacy that labs have been checked, or the presence of a physician-qualifying sticker on the prescription.

- Patients be subjected to monitoring:

Examples include lab tests monitored on a specified periodic basis and contacting the prescriber at specified times after starting treatment.

- Patients enroll in a patient registry:

Drug access may be contingent on patient enrollment. Data collected may include clinical outcomes, clinical and laboratory data, safety information, compliance data, and impact of tools on ensuring compliance and outcomes.

- Other postmarketing actions may be taken, such as “enhanced surveillance” (often this is ill-defined and turns out to be just a bit more due diligence on spontaneously reported cases), targeted safety studies, Large Simple Safety Studies (LSSS), epidemiologic studies (e.g., comparative observational studies), and drug utilization studies.

- ETASUs should not be confused with postmarketing commitments (studies or other procedures promised to FDA after NDA approval and as a condition of the approval), which may or may not be part of a REMS.

Implementation System: Details may be required and include a description of the distribution system of the contents of the REMS and certification of wholesalers and distributors to ensure they comply. Examples of implementation methods include the maintenance of a validated database to track certified prescribers/dispensers, and periodic audits of pharmacies, practitioners, and others to ensure compliance with ETASUs. The assessments should be done at least at 18 months, 3 years, and 7 years. Changes along the way to improve the REMS are encouraged if the goals are not being met. All changes must be approved by the FDA.

Further details and an example of a mock REMS are found in the FDA draft guidance cited above.

REMS that are in place are available for review on FDA’s website. This site is worth reviewing for anyone involved in REMS preparation or review. The drug name, date of REMS approval, and contents (as PDF files) are available (Web Resource 30-6).

As of this writing, the most REMS are limited only to medication guides. A few also have communication plans and a handful also have ETASUs. Some are rather extensive, such as the REMS developed by a joint FDA/industry working group on opioids (Web Resource 30-7).

Classwide REMS

Classwide REMS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree