Right Hemicolectomy for Treatment of Cancer: Open Technique

Bruce G. Wolff

Jennifer Y. Wang

Right hemicolectomy is indicated for malignant neoplasms of the cecum and right colon. This is traditionally performed with the open technique, although since the advent of laparoscopy, in many centers laparoscopy has become the primary approach for patients with amenable right-sided cancers. The clinical outcomes of surgical therapy (COST) study and many others support laparoscopic right hemicolectomy as having equivalent oncologic outcomes as the open technique. However, in certain patients and in settings in which advanced laparoscopy is not available, open right hemicolectomy remains the standard of care. Other pathologic entities for which a right hemicolectomy would be performed include adenomatous polyps that cannot be endoscopically addressed, carcinoid tumors, inflammatory bowel disease (namely Crohn disease), and various tumors of the appendix.

Adenocarcinoma of the right colon too often presents with little warning. When signs or symptoms exist, they can take the form of occult bleeding and/or anemia, partial obstruction, and, on occasion, a palpable mass in the right lower quadrant. The tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) classification of malignant colon cancer is the standard staging system that we use. According to this system, adenocarcinoma invading the submucosa is classified as T1, invading the muscularis propria as T2, invading serosa or pericolic fat as T3, or invading into adjacent organs as T4. Although malignant neoplasms begin locally, they can, over time, spread through regional lymph vessels or by hematogenous dissemination. Carcinomatosis occurs if the tumor has spread to involve multiple separate areas within the abdominal cavity, such as in the omentum or studding the peritoneal surfaces, and is typically felt to be beyond surgical cure.

Adjuvant therapies such as chemotherapy and less commonly radiation therapy in general serve only as adjunct to the mainstay of treatment, which remains surgical resection. These adjuvant therapies are based on surgical and pathologic stage. In the situation of initial presentation with metastatic disease, neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be offered prior to surgery unless the patient is symptomatic from the primary tumor. A key factor in a good oncologic resection is the number of lymph nodes harvested. Many studies support that the number of lymph nodes examined correlates with overall survival, and the American Joint Committee on Cancer has deemed that a minimum of 12 lymph nodes need to be examined for adequate staging. The number of lymph nodes evaluated can be affected by patient factors (obesity), surgical factors (not high enough ligation on the vascular pedicle), and pathologic factors (insufficient techniques to identify all lymph nodes in the specimen). Insufficient lymph nodes for examination may result in understaging of cancer and thus undertreatment of someone who may have been a candidate for adjuvant therapy based on Stage III disease.

Because right colon cancer rarely presents with obstruction, the surgeon and primary care physician have the luxury of time to complete the proper staging and workup for most patients. Routine workup for planning treatment of a right colon cancer includes complete colonoscopy to confirm pathologic diagnosis and clear the rest of the colon, which has a 3% to 5% rate of synchronous cancer. If the tumor is small and not palpable, or if a laparoscopic approach is anticipated, it is essential that the tumor be tattooed endoscopically before surgery, unless it is clearly within or in view of the cecum. This will help the surgeon obtain an adequate distal resection margin. Additional workup should include a chest radiograph, complete blood count, liver function tests, and carcinoembryonic antigen measurement. As laparoscopic surgery becomes more prevalent, computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis has become more useful to fully evaluate patients for abdominal metastasis, locally advanced disease, and liver metastasis. Consideration must also be given to the possibility of familial syndromes (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) and the need for genetic and microsatellite instability tests in selected patients with strong family history, early onset, and right-sided lesions.

Preparation

There are varying opinions about the use of mechanical bowel preparation prior to surgery. While all patients undergoing colon surgery were traditionally given bowel preparation, more recent studies including meta-analyses of retrospective studies and even randomized clinical trials found no benefit, and possibly even detrimental effects, of bowel preparation with respect to the risk of wound infection or anastomotic leak. Many surgeons still prefer to use bowel preparation, as performing surgery with a well-prepped colon can make the bowel easier to manipulate and manage, and is certainly beneficial if an intraoperative colonoscopy is warranted. There are many varieties of bowel preparations available on the market today. There is also benefit from preoperative intravenous antibiotics given within 60 minutes of incision to decrease the occurrence of wound complications.

Right Colectomy

Appropriate attention to patient positioning is essential for ease of operation and patient safety. It is our practice to position patients on the table in a supine position. Arms are typically tucked in and well padded to prevent nerve injury. Ankle straps are often used to allow for Trendelenburg position. The surgeon stands on the patient’s left and across from the first assistant on the right. If a second assistant is needed, it is most helpful if that assistant is on the surgeon’s left early in the case and then on the other assistant’s right later in the case as the hepatic flexure is mobilized.

Once the patient has been placed under general anesthesia, prepared, and draped, a midline incision is made, passing around the right side of the patient’s umbilicus. Incision length is in direct proportion to the body habitus of the patient. Once the abdomen is entered, a thorough exploration of the abdomen is the first order of business. The liver is palpated, the gallbladder assessed for stones, and the surrounding organs of the upper and midabdomen are examined. The small bowel is run from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve. The stomach, kidney, pancreas, spleen, aorta, and iliac vessels are palpated and examined for evidence of disease. In women, the uterus and ovaries are inspected for any abnormalities. After assessing the abdomen

for metastatic disease and surgical resectability, the tumor and surrounding structures are addressed.

for metastatic disease and surgical resectability, the tumor and surrounding structures are addressed.

Special consideration should be given to locally aggressive tumors such as those that involve adjacent organs (T4). If adjacent organs such as duodenum, small bowel, omentum, and retroperitoneal structures such as the ureter or gonadal vessels are involved, every attempt must be made to complete an en bloc resection. At no time should a surgeon attempt to surgically separate intra-abdominal structures from the tumor, as this would violate oncologic surgical principles and potentially adversely affect the patient outcome. An R0 resection is the goal of every operation. Rarely, a primary tumor is found intraoperatively to have unresectable metastatic disease despite preoperative workup. In general, our practice has been to resect the primary tumor to prevent the future possibility of hemorrhage or obstructive complications. If the surgeon believes the primary tumor cannot be removed safely, a bypass procedure should be performed to prevent future obstruction.

Vascular Anatomy

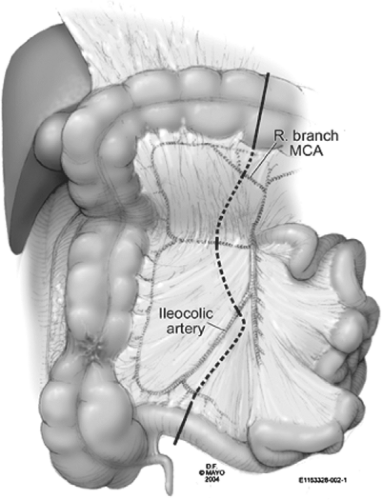

The avascular window between the right branch of the middle colic artery and the right or ileocolic artery, as well as between the ileocolic and the last ileal branches, are important anatomic landmarks. It is well known that the right colic artery rarely branches directly off the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). It is most often (90% of the time) a branch of the ileocolic artery, and therefore rarely requires separate ligation. The vessels that must be ligated for a right colon resection include the ileocolic, right colic, and the right branch of the middle colic.

Surgical Dissection: Open Technique

The line of resection for a right colon cancer depends somewhat on the location of the tumor. For tumors located in the cecum, a 10-cm margin of terminal ileum is generally taken. On the other hand, if the tumor is located in the ascending colon, only a few centimeters of ileum are required as a margin. This line of resection should extend to the right side of the transverse colon at the level of the right branch of the middle colic vessels (Fig. 1). Care must be taken to preserve the main branch of the middle colic vessels. The right colic and ileocolic vessels are taken at their origins to ensure proper lymph node harvest. Omental attachments to the right colon are generally removed with the specimen.

Mobilization of the right colon begins by separating the retroperitoneal structures (gonadal vessels and ureter) from the terminal ileum and cecum. This is performed by incising the peritoneal attachments to these structures laterally and rotating the cecum anteriorly and medially (Fig. 2). Once this mobilization is completed, the medial and inferior attachments to the cecum and terminal small bowel are incised up toward the junction of the third and fourth portions of the duodenum. A sponge is often helpful to gently separate the filmy adhesions to the retroperitoneum posteriorly as mobilization continues in the superior direction. Of course, care is taken during this dissection to identify and posteriorly displace the gonadal vessels and ureter. Mobilization of the ileocolic vessel is complete once the surgeon has identified the middle colic as it crosses the duodenum. Continuing the lateral dissection up and around the hepatic flexure, the surgeon’s index finger provides the plane of dissection for cauterization by the first assistant (Fig. 3). Retracting the midtransverse colon inferiorly, one can complete the exposure of the hepatic flexure. The thin plane between the mesocolon and the gastrocolic ligament can be developed bluntly and dissected to complete the flexure mobilization. As one mobilizes the gastrocolic ligament, there may be a few vessels that need ligation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree