Figure 33-1 Evaluation of monoarticular arthritis. CBC, complete blood count; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; WBC, white blood cells. Modified from Guidelines for the initial evaluation of the adult patient with acute musculoskeletal symptoms. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Clinical Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:1–8.

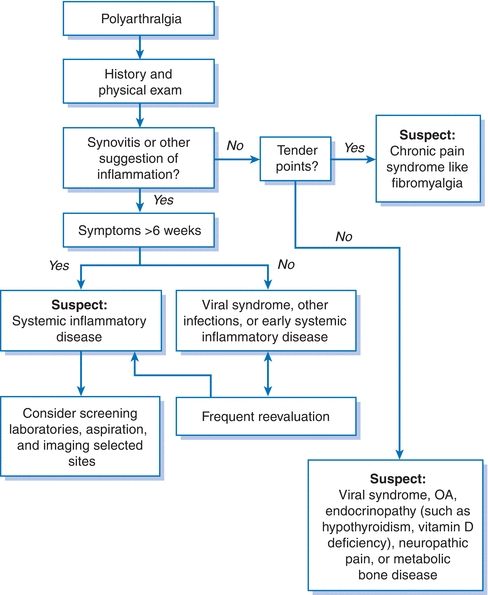

Figure 33-2 Evaluation of polyarthralgia. Modified from Guidelines for the initial evaluation of the adult patient with acute musculoskeletal symptoms. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Clinical Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:1–8.

Clinical Presentation

History

- Characteristic inflammatory symptoms include swelling, heat, redness, morning stiffness, stiffness after inactivity (the so-called gelling phenomenon), and sometimes fever.

- Mechanical symptoms include pain with activity that is relieved with rest, minimal morning stiffness, joint locking or giving out, and lack of swelling or heat.

- Location of pain can help provide clues as to the etiology.

- History of precedent traumatic injury might suggest degenerative arthritis of the joint, whereas the classic presentation of podagra with inflammation of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint suggests gout.

- Osteoarthritis (OA) tends to affect knees, hips, and the first carpometacarpal joint in the hand.

- Multiple pain complaints and diffuse tender points suggest a chronic pain syndrome such as fibromyalgia or depression.

- History of precedent traumatic injury might suggest degenerative arthritis of the joint, whereas the classic presentation of podagra with inflammation of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint suggests gout.

Physical Examination

- Gait: Observing the patient walking away, turning, and walking back can help localize the source of pain.

- Hand: Have the patient make a fist and inspect the dorsum of the hand; observe supination; and inspect the palm of the hands. Look carefully at each of the joints, and palpate the metacarpophalangeal joints for swelling or tenderness.

- Shoulder: Ask the patient to put both hands together above the head and observe any abnormal movement of the scapula; put both hands behind the head; and put both hands behind the back (normally, the thumb tip can reach the tip of the scapula).

- Cervical spine: Have the patient touch the tip of the chin to chest, look up, and look over each shoulder.

- Lower spine: Ask the patient to bend forward to touch the toes without bending the knees, and observe movement of the lumbar spine (normally, there should be reversal of lordosis with flexion of the lumbar spine).

- Hip: The FABER maneuver (flexion-abduction-external rotation) is performed by first having the patient put his or her heel on the contralateral knee; the examiner then presses down on the medial knee, putting the hip into external rotation. The important finding is where pain is elicited. Pain in the groin is indicative of hip joint pathology, but pain may also be elicited from the SI joint and the lateral aspect of the hip from the trochanteric bursa.

- Knee: The patient should be able to straighten the knee fully and flex it so the heel almost touches the buttocks. Look for symmetry and effusions. The patella can be held in place with one hand and normally should have little give. In the presence of an effusion, one can elicit a bulge sign.

- Ankle: One should look for limitations in flexion and extension and inversion and eversion.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

- Few rheumatology tests are designed to serve as independent diagnostic tools, and test results must always be interpreted in a clinical context.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is a very nonspecific indicator of inflammation and is often elevated due to increased fibrinogen during inflammation. Anemia, kidney disease (especially proteinuria), and aging can all elevate the ESR in the absence of inflammation.

- C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute-phase reactant and a component of the innate immune system; levels rise rapidly with inflammation and infection and fall quickly as inflammation resolves.

- Unlike the ESR, the CRP is not influenced by anemia and abnormal erythrocytes.

- Today, most laboratories perform a high-sensitivity assay for the presence of CRP that can identify minute increases.

- Unlike the ESR, the CRP is not influenced by anemia and abnormal erythrocytes.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF) is an immune complex of immunoglobulin (Ig) M that binds to the Fc portion of IgG and is elevated in approximately 80% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, RF can also be elevated in Sjögren syndrome, sarcoidosis, chronic infections, and other conditions where immune complexes are formed.

- Anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA or anti-CCP) recognize a posttranslational modification of proteins that is thought to occur in the synovium of patients with RA. The assay is now routinely performed, has a higher specificity for the diagnosis of RA, and may be predictive of progressive joint disease.2

- Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA): ANCA detects antibodies against neutrophils and is reported as either a cytoplasmic pattern (c-ANCA) or a perinuclear pattern (p-ANCA).

- A positive ANCA test is only significant when confirmatory ELISA demonstrates that the c-ANCA represents anti–proteinase-3 (PR3) or the p-ANCA represents antimyeloperoxidase (MPO).

- Antibodies against PR3 are specific for granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly known as Wegener granulomatosis).

- Antibodies against MPO are less specific and are seen in conditions such as microscopic polyangiitis and Goodpasture syndrome (in up to 30% of patients).

- A positive ANCA test is only significant when confirmatory ELISA demonstrates that the c-ANCA represents anti–proteinase-3 (PR3) or the p-ANCA represents antimyeloperoxidase (MPO).

- The antinuclear antibody (ANA) test detects antibodies that bind to nuclear antigens. ANA is a very sensitive test for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, sensitivity >95%) and may be abnormal in many other autoimmune diseases such as scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, and polymyositis. However, because the specificity of the ANA is low, a positive ANA alone is seldom useful. Furthermore, this highly sensitive test produces many confusing false positives and should only be obtained in patients whose clinical presentation suggests lupus or a related disease.

- Antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens (ENA): This test encompasses a panel of saline-soluble nuclear antigens. This panel detects four autoantibodies: anti-SM (Smith, SLE), anti-RNP (ribonucleoprotein, SLE, and mixed connective tissue disease), and SSA and SSB (Sjögren syndrome, SLE, and neonatal lupus). SSA and SSB are also known as anti-Ro and anti-La, respectively.

- Anti–Scl-70 antibodies: Directed against topoisomerase I and associated with diffuse scleroderma.

- Anticentromere antibodies: Directed against 70/13-kDa proteins that make up the centromere complex and associated with limited scleroderma. This is the discretely speckled pattern on the ANA test.

- Anti–Jo-1 antibodies: Directed against histidyl tRNA synthetase and associated with myositis with interstitial lung disease, arthritis, and mechanic’s hands (known as the antisynthetase syndrome).

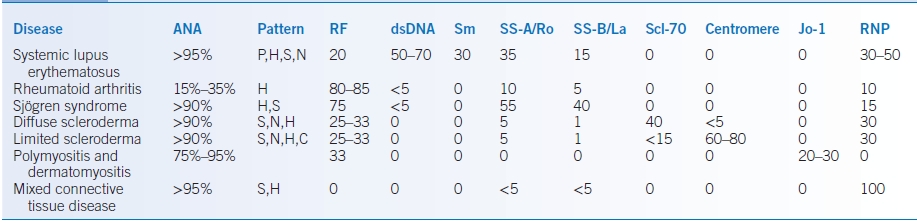

- Table 33-1 presents an overview of the various autoantibodies and their disease associations.3

TABLE 33-1 Autoantibodies and Disease Associations

C, centromere; H, homogenous or diffuse; P, peripheral or rim; N, nucleolar; S, speckled.

Data from Klippel JH, ed. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, 12th ed. Atlanta, GA: Arthritis Foundation; 2001.

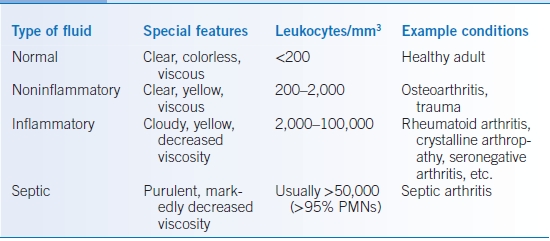

Synovial Fluid Evaluation

- Obtaining synovial fluid from a patient with undiagnosed arthritis, particularly monoarticular arthritis, can be very beneficial.

- The synovial fluid is often characterized by number of cells (especially polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs]), viscosity, and color.

- A Gram stain plus culture and the presence or absence of crystals can confirm the diagnosis (Table 33-2).

TABLE 33-2 Classification of Synovial Fluid

Imaging

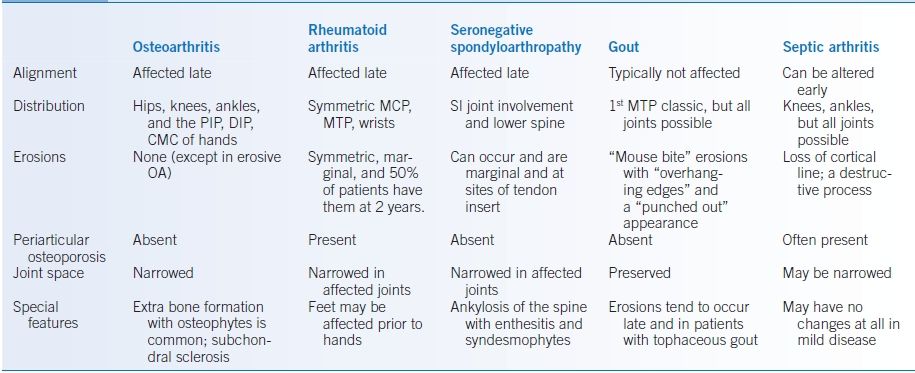

- Radiographic changes are common, even in early forms of arthritis.

- The distribution, appearance, severity, and other features of the radiography can help limit the differential diagnosis (Table 33-3).

TABLE 33-3 Radiographic Changes by Disease

CMC, carpometacarpal; DIP, distal interphalangeal; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; OA, osteoarthritis; PIP, proximal interphalangeal; SI, sacroiliac.

Osteoarthritis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- The typical joints involved in primary OA are lower cervical spine, lower lumbar spine, first carpometacarpal joint of the thumb, proximal interphalangeal joints (Bouchard nodes), distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (Heberden nodes), hip, knee, and first MTP joint.

- Primary OA is rarely seen in the following locations and, if present here, should raise the suspicion for secondary causes (trauma, inflammatory arthritis, etc.): metacarpophalangeal joints, shoulders, elbows, wrists, and ankles.

DIAGNOSIS

- History consists of mechanical pain (i.e., pain that is worse with activity and relieved with rest). Morning stiffness may be present, but usually lasts for <30 to 60 minutes.

- Examination reveals reduced range of motion, mild swelling, and bony hypertrophy. Small-to-moderate effusions may be present in the knee. Crepitus may be observed with range-of-motion examination.

- Laboratory tests are noncontributory except to rule out other causes of arthritis. Synovial fluid if drawn tends to have <2,000 cells/mm3.

- Radiographic findings are indicated in Table 33-3.

TREATMENT

Guidelines for the treatment of OA have been published by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).4

Medications

- Acetaminophen at doses of 1,000 mg tid is often helpful and may be as beneficial as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for some patients. Maximum total daily dose should not exceed 2,000 mg in those with significant liver disease.

- NSAIDs including those that are selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are commonly prescribed and have been specifically demonstrated to relieve the signs and symptoms of OA. Patients may require a trial of several of these agents to find the most efficacious. Major toxicities include but are not limited to the following:

- Gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity particularly if certain risk factors are present (e.g., age ≥65, oral steroids/anticoagulant use, and history of ulcer disease/GI bleeding).3 The use of celecoxib or a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) along with a nonselective NSAID may dramatically reduce this risk.5

- Nephrotoxicity and nephrogenic sodium retention.

- Cardiovascular risks. Recent placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated an increased risk of thrombotic cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction (MI) and strokes with COX-2 selective NSAIDs.6 It is likely that this cardiovascular risk extends to all NSAIDs.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity particularly if certain risk factors are present (e.g., age ≥65, oral steroids/anticoagulant use, and history of ulcer disease/GI bleeding).3 The use of celecoxib or a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) along with a nonselective NSAID may dramatically reduce this risk.5

- Topical capsaicin, diclofenac, and lidocaine can improve symptoms particularly if few joints are involved.

- Analgesics such as tramadol and opiates are sometimes indicated. With chronic opiate use, tolerance typically develops, requiring progressively higher doses.

Joint Injections

Intra-Articular Steroids

- Intra-articular steroids have been used for the treatment of OA since the 1950s and are routinely performed by general practitioners. Their use should be limited to those with training in the procedure.

- Available steroid preparations include triamcinolone hexacetonide (fluorinated), triamcinolone acetonide (fluorinated), methylprednisolone acetate (nonfluorinated), and dexamethasone.

- Dose varies based on location, and no controlled studies exist to guide therapy. General guidelines are as follows:

- Large joint (knee and shoulder), 40 to 80 mg (1 to 2 mL)

- Medium joint (wrist, ankle, elbow), 30 mg

- Small spaces (metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, tendon sheaths), 10 mg

- Large joint (knee and shoulder), 40 to 80 mg (1 to 2 mL)

- Precautions:

- Do not inject through cellulitis or psoriatic skin lesion.

- Do not inject the same joint more than three to four times a year.

- Infections can occur but are rare, occurring in only 6 of >100,000 procedures in one classic series.7

- Steroid-induced crystalline arthritis can occur because the steroid preparations involve crystalline glucocorticoid. The reactions usually occur within 24 hours after injection and last 2 to 3 days similar to gout, while septic arthritis from an injection tends to occur >48 hours after the injection.

- Do not inject through cellulitis or psoriatic skin lesion.

Hyaluronic Acid Analog Injections

- The most commonly used preparation is hylan G-F 20, which can be given as a single injection that is administered once every 6 months.

- Early studies have shown efficacy equal to naproxen in the treatment of OA, but a large meta-analysis of several studies showed little benefit.8 It is possible that a subset of patients may benefit, and this therapy can be considered in patients with early disease.

- Iatrogenic joint infection, postinjection inflammation (pseudoseptic reaction), and aspiration-proven pseudogout can complicate hyaluronate injections.

Nonpharmacologic Measures

- Nonpharmacologic measures include weight loss, use of a cane or walker, braces and other orthotics, and acupuncture.

- Exercise with and without formal physical therapy. Muscle strength surrounding an affected joint can help stabilize the joint, relieve pain, and possibly reduce progression of joint space narrowing.

Surgery

- Orthopedic consultation for joint replacement of hip, knee, or shoulder should be considered for patients who have exhausted conservative options.

- The timing of surgery is a complicated decision but is primarily based on the severity of the patient’s symptoms.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- RA, the prototypical inflammatory arthritis, affects approximately 1% of the population and accounts for a significant degree of morbidity in affected patients.

- RA is a chronic, polyarticular inflammatory arthritis with a symmetric distribution that affects the hands and feet.

- The etiology is still not well understood, but identification and characterization of biologic mediators of the inflammatory response associated with RA has led to the development of new treatments.9

DIAGNOSIS

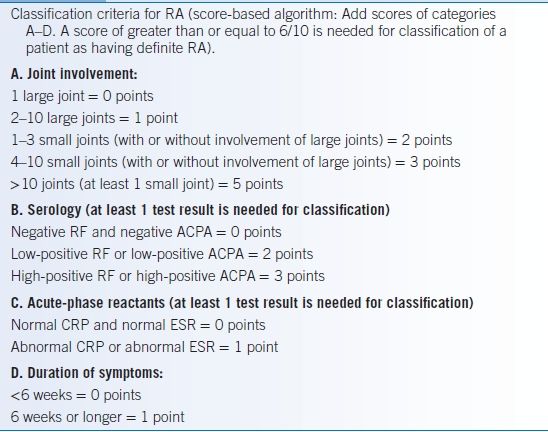

The ACR has specified criteria associated with RA (Table 33-4).10 These criteria help outline the symptoms at presentation, but all may not be present in the early course of the disease.

TABLE 33-4 ACR 2010 Criteria for the Classification of Acute Rheumatoid Arthritis

Modified from Aletaha D, Negoit T, Silman AJ, et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1580–1588.

Extra-Articular Manifestations

- Pulmonary: RA can cause several types of pulmonary disease such as isolated rheumatoid lung nodules, pleural effusions, or interstitial lung disease, which can progress to fibrosis.

- Felty syndrome is a syndrome of seropositive RA, neutropenia, and splenomegaly. It usually occurs in patients with long-standing severe disease and can result in increased risk of infection.

- Ocular: Severe ocular dryness (keratoconjunctivitis sicca) is the most common ocular problem. Scleritis with a painful red eye that may lead to a thinning of the sclera indicates severe refractory disease and often requires aggressive treatment both systemically and topically.

- Vasculitis: Rheumatoid vasculitis can affect any blood vessel, but the most common manifestation is distal arteritis ranging from nail fold infarcts to gangrene of the fingertips.

- Cardiovascular risk: Chronic inflammation may play a role in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Patients with chronic inflammatory conditions have been shown to be at increased risk of macrovascular complications such as stroke and MI. Indeed, the same is true for RA, and aggressive therapy to reduce cardiovascular risks is an important aspect of RA management.11

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

- Refer to Approach to the Patient with Painful Joints above regarding RF, ACPA, ESR, and CRP.

- Complete blood count (CBC), CMP, and hepatitis panel (to rule out hepatitis C as a cause of a positive RF and arthralgias as well as to avoid using hepatotoxic medications in patients with chronic viral hepatitis) should also be performed.

Imaging

- Classical findings on plain radiography include soft tissue swelling, joint space loss, periarticular osteoporosis, and erosions (which eventually develop in the large majority of patients). Musculoskeletal ultrasound can be useful in demonstrating synovial proliferation and inflammation prior to radiographic abnormalities.

- Baseline chest radiography is warranted given the possibility of pulmonary involvement.

TREATMENT

Many aspects of RA diagnosis and treatment can be managed in the primary care setting including establishing the diagnosis early, documenting baseline activity, educating patients, initiating NSAID therapy, referral for physical/occupational therapy, and prescribing disease-modifying therapy within 3 months of diagnosis (e.g., corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, or methotrexate [MTX]). Patients should be reassessed frequently and referred to a rheumatologist if the response is inadequate.12 Early treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has the potential to retard the progression of disease.

Medications

Most patients with RA benefit symptomatically from the use of NSAIDs, but they do not prevent the progression of bone and cartilage damage.

Glucocorticoids

- Glucocorticoids (especially prednisone) in low doses are extremely effective for promptly reducing the symptoms of RA and can be considered to help patients recover their previous functional status.

- Unfortunately, short courses of oral corticosteroids produce only interim benefit and chronic therapy is often required to manage symptoms and prevent progression of disease.

- Corticosteroids are particularly helpful in treating patients with severe functional impairment or while awaiting clinical response from a slow-acting DMARD.

- Side effects of corticosteroids are many and include hyperglycemia, adrenal insufficiency, osteopenia, and avascular necrosis. If a dose equivalent to 5 mg or greater of prednisone is to be used for longer than 3 months, then a bisphosphonate should be used to prevent bone loss in the absence of contraindications.13

- Intra-articular steroids are particularly useful in patients with a flare of RA in a monoarticular or oligoarticular pattern.

Hydroxychloroquine

- Hydroxychloroquine is indicated for mild-to-moderate RA.

- It is effective at doses of 400 mg PO daily not to exceed 6 mg/kg but is contraindicated in patients with renal or hepatic insufficiency.

- The side effect of macular toxicity is extremely unusual at these doses and rarely occurs before 5 years of treatment. Nonetheless, an ophthalmologist should perform a baseline examination and monitor the patient at least annually.

Sulfasalazine

- Sulfasalazine is also indicated for mild-to-moderate RA and in those who are poor candidates for methotrexate therapy.

- It should be initiated at 500 mg PO bid and gradually increased to 1,000 to 1,500 mg PO bid.

- GI intolerance is common and may be reduced with an enteric-coated preparation.

- It is contraindicated in those allergic to sulfa antibiotics and those with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Severe/fatal skin reactions have occurred.

- Monitoring of liver tests and blood counts is required.

Methotrexate

- MTX is generally considered to be the DMARD of choice for most RA patients. The usual maintenance dose is 7.5 to 20 mg/week orally.

- If MTX is at least partially effective, it should be continued as other agents are added.

- Common side effects include stomatitis, nausea, diarrhea, and thinning of the hair. It is teratogenic.

- Supplementation with folic acid at doses of 1 to 3 mg PO daily can reduce side effects, although efficacy may be somewhat attenuated.

- Serious adverse reactions include hepatotoxicity, lung toxicity, and bone marrow suppression.

- MTX should only be prescribed by those experienced in its use, and careful monitoring of liver tests, serum creatinine, and blood counts is required. It should be used with great caution in the elderly and those with reduced renal function.

Leflunomide

- Leflunomide is a pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor that has been shown to have efficacy comparable to that of MTX in the treatment of RA and may be used in combination with MTX.

- Common side effects include diarrhea, rash, and alopecia. It is teratogenic.

- Monitoring of liver tests and blood counts is required due to the risk of hepatotoxicity and bone marrow suppression. Leflunomide should only be prescribed by those experienced in its use.

Tofacitinib

- Tofacitinib is a small molecule inhibitor of JAK2, a kinase that operates downstream of multiple cytokines and growth factors. Tofacitinib has shown similar efficacy to methotrexate and adalimumab and has been effective in patients who have failed other therapies.

- Side effects include headache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Elevated cholesterol and transaminase levels as well as neutropenia can occur.

- Tofacitinib requires regular monitoring of blood counts, liver enzymes, and cholesterol. Tofacitinib should only be prescribed by those experienced in its use.

Biologic DMARDs

- Etanercept (Enbrel) is a human fusion protein consisting of both the soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor and the Fc component of IgG.

- Infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), golimumab (Simponi), and certolizumab (Cimzia) are monoclonal antibodies against TNF-α.

- Anakinra (Kineret) is a recombinant interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist.

- Abatacept (Orencia) is a selective costimulation modulator (inhibitor) and a fusion protein consisting of an IgG Fc fused to the CTLA4 extracellular domain. Studies have shown it to be efficacious in patients who have failed prior treatment with anti-TNF therapy.14

- Rituximab (Rituxan) is a chimeric monoclonal antibody against CD20 and results in the destruction of B cells. This agent has been shown to be efficacious in patients with inadequate responses to TNF inhibitors.15

- Tocilizumab (Actemra) is a monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor.

- Consideration of biologic DMARDs is appropriate for patients unresponsive to oral DMARDs.

- Toxicities of the biologic DMARDs include opportunistic infections, disseminated TB, drug-induced lupus, worsened heart failure, demyelinating syndromes, colon perforation, and possibly increased risk of lymphoma.

Combination Therapy

- Combination regimens of multiple DMARDs or DMARDs plus biologic agents may be particularly effective in RA.9 Such combined therapy should only be done in conjunction with a rheumatologist.

- Data show that virtually all DMARDs and biologic DMARDs are more effective when combined with MTX.

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapies

- Occupational therapy usually focuses on the hand and wrist and can help patients with splinting, work simplification, activities of daily living, and assistive devices.

- Physical therapy assists in stretching and strengthening exercises for large joints such as the shoulder and knee, gait evaluation, and fitting with crutches and canes.

- Moderate exercise is appropriate for all patients and can help to reduce stiffness and maintain joint range of motion.

- In general, an exercise program should not produce pain for >2 hours after its completion.

Surgical Management

Orthopedic surgery to correct hand deformities and replace large joints such as the hip, knee, and shoulder should also be considered when pain cannot be controlled adequately with medications.

Infectious Arthritis and Septic Bursitis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Infectious arthritis is generally categorized into gonococcal and nongonococcal infection.

- The usual presentation is with fever and acute monoarticular arthritis, although multiple joints may be affected by hematogenous spread of pathogens.

- Nongonococcal infectious arthritis in adults tends to occur in patients with previous joint damage or compromised host defenses.

- Nongonococcal septic arthritis is caused most often by Staphylococcus aureus (60%) and Streptococcus spp.

- Gram-negative organisms are less common, except with IV drug abuse, neutropenia, concomitant urinary tract infection, and prosthetic joints.

- Nongonococcal septic arthritis is caused most often by Staphylococcus aureus (60%) and Streptococcus spp.

- Gonococcal arthritis is more common than nongonococcal septic arthritis and is the most common cause of monoarticular arthritis in patients between the ages of 20 and 30.16 The clinical spectrum of disease often includes migratory or additive polyarthralgias, followed by tenosynovitis or arthritis of the wrist, ankle, or knee, and asymptomatic dermatitis on the extremities or trunk.

- Nonbacterial infectious arthritis is common with many viral infections, especially hepatitis B, rubella, mumps, infectious mononucleosis, parvovirus, enterovirus, adenovirus, and HIV. Hepatitis C infection is associated with the formation of cryoglobulinemia, which can present as a polyarticular inflammatory arthritis with glomerulonephritis, cutaneous vasculitis, and mononeuritis multiplex.

- Septic bursitis, usually involving the olecranon or prepatellar bursa, can be differentiated from septic arthritis by localized, fluctuant superficial swelling with relatively painless joint motion (particularly extension). Most patients have a history of previous trauma to the area or an occupational predisposition (e.g., so-called housemaid’s knee and writer’s elbow). Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen.

DIAGNOSIS

- Joint fluid examination, including Gram stain of a centrifuged pellet, and culture are mandatory to make a diagnosis and to guide management.

- A joint fluid leukocyte count is useful diagnostically and as a baseline for serial studies to evaluate response to treatment.

- Cultures of blood and other possible extra-articular sites of infection also should be obtained.

- In contrast to nongonococcal septic arthritis, Gram staining of synovial fluid and cultures of blood or synovial fluid are often negative in gonococcal arthritis.

TREATMENT

- Hospitalization is indicated to ensure drug compliance and careful monitoring of the clinical response.

- IV antimicrobials provide good serum and synovial fluid drug concentrations. Oral antimicrobials are not appropriate as initial therapy, and there is no role for intra-articular antibiotic therapy.

- Arthrocenteses should be performed daily or as often as necessary to prevent reaccumulation of fluid and monitor response to therapy.

- General supportive measures include splinting of the joint, which may help to relieve pain. However, prolonged immobilization can result in joint stiffness.

Medications

- An NSAID or selective COX-2 inhibitor is often useful to reduce pain and to increase joint mobility but should not be used until response to antimicrobial therapy has been demonstrated by symptomatic and laboratory improvement.

- Initial therapy is based on the clinical situation and a carefully performed Gram stain, which reveals the organism in approximately 50% of patients.17

- With a positive Gram stain, antibiotic coverage can be adjusted accordingly.

- With a nondiagnostic Gram stain, antibiotics should be selected to cover S. aureus, Streptococcus spp., and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in otherwise healthy patients, whereas broad-spectrum antibiotics are appropriate in immunosuppressed patients.

- IV antimicrobials are usually given for at least 2 weeks, followed by 1 to 2 weeks of oral antimicrobials, with the course of therapy tailored to the patient’s response. Infectious disease consultation can be helpful for treatment.

- With a positive Gram stain, antibiotic coverage can be adjusted accordingly.

- Treatment for gonococcal arthritis begins with an intravenous antibiotic for the first 1 to 3 days, generally ceftriaxone, 1 g daily or ceftizoxime, 1 g every 8 hours.

- Response to IV antibiotics is usually noted within the first 24 to 36 hours of treatment.

- After initial clinical improvement, therapy is continued with an oral antibiotic to complete 7 to 10 days of treatment.

- Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg bid, or amoxicillin/clavulanate, 500/875 mg bid, can be used, although resistance to fluoroquinolones is increasing and decisions regarding treatment should be based on regional guidelines.18

- Response to IV antibiotics is usually noted within the first 24 to 36 hours of treatment.

- Viral arthritides are generally self-limited, lasting for <6 weeks, and respond well to a conservative regimen of rest and NSAIDs.

- Septic bursitis should be treated with aspiration, which should be repeated if fluid reaccumulates. Oral antibiotics and outpatient management are usually appropriate, and surgical drainage is rarely indicated.

Surgical Management

Surgical drainage or arthroscopic lavage and drainage are indicated in the following circumstances:

- A septic hip that cannot easily be accessed by arthrocentesis

- Joints in which the anatomy, large amounts of tissue debris, or loculation of pus prevent adequate needle drainage

- Septic arthritis with coexistent osteomyelitis

- Joints that do not respond in 4 to 6 days to appropriate therapy and repeated arthrocenteses

- Prosthetic joint infection

Gout

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Deposition of microcrystals in joints and periarticular tissues results in gout, pseudogout, and basic calcium phosphate (BCP) disease.19

- Gout is caused by the accumulation of excess amounts of uric acid in the body, leading to deposition of monosodium urate crystals when levels exceed solubility.

- Gout can produce four distinct clinical syndromes: acute gouty arthritis, chronic tophaceous gout, urate nephropathy, and urate nephrolithiasis.

- All complications of gout result from hyperuricemia. In 90% of cases, this occurs as a result of underexcretion of urate.

- Risk factors include male sex, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, renal dysfunction, alcohol, dehydration, and drugs (e.g., low-dose salicylates, diuretics, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, levodopa, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus).20

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- Acute gouty arthritis presents with acute pain and swelling, usually of a single joint.

- Commonly affected joints include the great toe MTP joint (i.e., podagra), ankle, knee, and wrist.

- Episodes often occur at night and frequently accompany acute medical illnesses, postsurgical periods, dehydration, fasting, or heavy alcohol consumption.

- Pain is severe, and immediate medical attention to provide pain relief is essential.

- Periarticular involvement is rare at presentation but may occur in long-standing cases.

- Intense periarticular inflammation with desquamation of skin may give the appearance of cellulitis.

Diagnostic Testing

- Gout is diagnosed by polarized microscopy of synovial fluid demonstrating bright, negatively birefringent, needle-shaped crystals (often found within a PMN).

- Cell counts of synovial aspirates are usually consistent with an inflammatory arthritis (white cells in the tens of thousands, mostly PMNs).

- Aspiration of superficial tophi with a 25-gauge needle can also provide diagnostic material.

TREATMENT

NSAIDs

- NSAIDs are particularly effective and are the treatment of choice for acute gout.

- They should be started in maximal doses and tapered over several days once the gouty flare has subsided.

- A common high-dose NSAID regimen is indomethacin 50 mg PO qid given for several days until relief is obtained, followed by 50 mg tid for 2 to 3 days, 50 mg bid for 2 to 3 days, 50 mg/day for a few days, and then discontinue.

- Naproxen, ibuprofen, sulindac, and other NSAIDs are also effective and are generally better tolerated than high-dose indomethacin.

Colchicine

- The current approved dose of colchicine for acute gout is 1.2 mg PO then 0.6 mg 1 hour later as needed. Avoid this treatment in patients on colchicine prophylaxis and taking a CYP3A4 inhibitor. Dose adjustment is not needed for renal impairment but should not be repeated for 2 weeks. For patients on hemodialysis, only 0.6 mg should be given and not repeated.

- The traditional dose of colchicine every hour is obsolete and should not be used.

- IV colchicine is no longer available.

Glucocorticoids

- Oral steroids can be used when other therapies are contraindicated. Prednisone initiated at 60 mg/day and tapered rapidly can provide adequate symptomatic relief while avoiding toxicities of long-term steroid use.

- Intra-articular aspiration and corticosteroid injection is appropriate for large joints and is an excellent choice for patients who are not good candidates for NSAIDs. Because the knee joint often has a tense effusion, aspiration of as much fluid as possible can bring immediate relief, followed by injection of 1 to 2 mL corticosteroid with an equal volume of 1% lidocaine. A volume of 1 mL is appropriate for the ankle.

Biologic Therapy

Pegloticase (Krystexxa) is a pegylated, recombinant uricase that can be administered to patients with chronic tophaceous gout who have had persistent disease and elevated uric acid despite maximum therapy with other uric acid–lowering medications. Patients must be tested for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency prior to administration. Pegloticase should only be prescribed by those experienced in its use.

Prophylactic Treatment

- Prophylactic treatment is advisable when patients have recurrent attacks several times per year.

- Colchicine, 0.6 mg once or twice daily, may be used (dose must be reduced for renal insufficiency or concomitant CYP3A4 inhibitors). Low-dose NSAIDs such as indomethacin, 25 mg bid, or naproxen, 250 mg bid, are another option. In patients with multiple recurrent attacks, uric acid–lowering therapy may be beneficial.

- Xanthine oxidase inhibitors (allopurinol and febuxostat) reduce uric acid production and are much easier to administer than probenecid.

- Xanthine oxidase inhibitors are indicated for recurrent attacks that are not controlled with colchicine or NSAIDs.

- Other indications for xanthine oxidase inhibitors include the presence of tophi, renal stones, and severe hyperuricemia (>13 mg/dL).

- Asymptomatic hyperuricemia should not be treated with these medications.

- A starting dose of allopurinol 100 mg/day can be increased after 2 to 4 weeks to 300 mg/day. Sometimes, higher doses (400 to 600 mg/day) are required. In the setting of renal impairment, starting dose should be 50 mg. The correct dose is that which reduces the serum uric acid to <6 mg/dL.

- Febuxostat should be started at 40 mg daily and may be increased to 80 mg daily if necessary. There are no data for higher doses or for use in patients with creatinine clearance <30.

- Xanthine oxidase inhibitors should not be started during an acute attack as they may cause a severe flare of the disease. Administration of prophylactic colchicine or low-dose NSAIDs before initiation of uric acid–lowering therapy may prevent the gouty attacks that sometimes accompany the initiation of allopurinol treatment. It is not necessary to discontinue use of a urate-lowering medication if a gout attack occurs after it is started.

- These medications are usually well tolerated, although a severe hypersensitivity syndrome can occur, especially with renal insufficiency and diuretic use.

- Xanthine oxidase inhibitors are indicated for recurrent attacks that are not controlled with colchicine or NSAIDs.

- Probenecid prevents tubular reabsorption of uric acid and can be used to enhance urinary excretion of uric acid provided that the baseline 24-hour urinary uric acid is 600 mg or less.

- If the 24-hour uric acid is >600 mg, increasing the urinary excretion of uric acid may precipitate uric acid kidney stones.

- Probenecid can be initiated at 500 mg PO daily and increased as needed, not exceeding 3,000 mg in three divided doses.

- Normal renal function is necessary for probenecid to be effective.

- Salicylates at any dose antagonize the effect of probenecid.

- If the 24-hour uric acid is >600 mg, increasing the urinary excretion of uric acid may precipitate uric acid kidney stones.

- A 12-year study of 730 patients with gout suggested that high levels of meat and seafood in the diet are associated with an increased risk of gout, whereas dairy products may be protective. The level of purine-rich vegetables and total protein intake was not associated with an increased risk of gout.21

Pseudogout

- Pseudogout is caused by deposition of calcium pyrophosphate crystals and tends to occur more often in elderly individuals.

- It may be precipitated by surgery and has been associated with hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, and hemochromatosis.

- Like gout, pseudogout tends to cause monoarticular attacks, especially in large joints.

- Symmetric involvement of the hands may mimic RA.

- Periarticular inflammation can be severe, mimicking cellulitis.

- Polarized microscopy of synovial fluid reveals rhomboid-shaped crystals that are positively birefringent.

- Radiographic studies may demonstrate chondrocalcinosis (especially knee, wrist, and symphysis pubis) but alone are not diagnostic of pseudogout.

- Treatment is the same as for gout, except that there is no role for uric acid–lowering therapy. Joint aspiration, alone or with steroid injection, often provides immediate relief of pain.

Apatite Deposition Disease

- Apatite deposition disease may present with periarthritis or tendonitis, particularly in the elderly and in patients with chronic renal failure.

- An episodic oligoarthritis may also occur, and apatite disease should be suspected when no crystals are present in the synovial fluid.

- Erosive arthritis may be seen, particularly in the shoulder (e.g., Milwaukee shoulder, a syndrome of large shoulder effusion, rotator cuff pathology, and the presence of basic calcium phosphate [BCP] crystals in synovial fluid).

- Hydroxyapatite complexes and BCP complexes can be identified only by electron microscopy, mass spectroscopy, or alizarin red staining, none of which are readily available to the clinician.

- The treatment of apatite disease is similar to that for pseudogout, except that recent studies suggest that early intervention and washing out the joint may help prevent progression of the disease.22

- Referral to orthopedic surgery may be required.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- SLE is a multisystem autoimmune disease of unknown etiology that commonly occurs in women of childbearing age. There is clearly a genetic predisposition.

- Manifestations of SLE are protean, and organ systems involved may include skin, heart, lungs, nervous system, kidneys, hematopoietic system, and joints.

- African-Americans and Hispanics have a worse prognosis.

- SLE can occur in the elderly, but when it does, it is usually milder.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

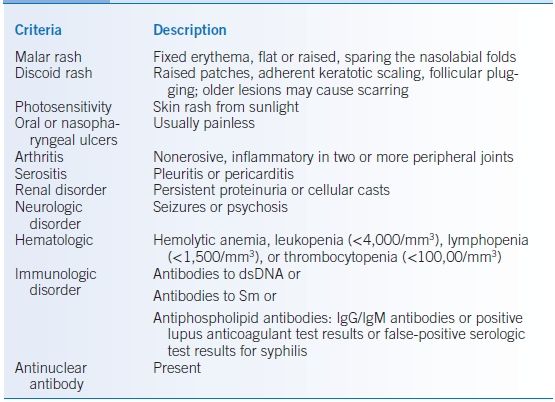

- The ACR has proposed 11 criteria for the diagnosis of SLE (Table 33-5).23

- For inclusion in clinical studies, a diagnosis requires that at least four of them be present at some point through the course of the disease. These criteria may be used to aid in the clinical diagnosis of lupus, recognizing that having four criteria in isolation is neither necessary nor sufficient for the diagnosis.23

TABLE 33-5 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Classification Criteria Definitions

dsDNA, double-stranded (native) deoxyribonucleic acid; Sm, Smith nuclear antigen.

Modified from Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271–1277.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree