53 Rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The cause of rheumatoid arthritis remains unclear with hormonal, genetic and environmental factors playing a key role. Genetic factors contribute 53–65% of the risk of developing this disease. The HLA-DR4 allele is associated with both the development and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Cigarette smoking is a strong risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis. A study of over 3000 women clearly linked the length of time that people had smoked with rheumatoid arthritis (Karlson et al., 1999). Patients with a smoking history of 25 years or more were increasingly likely to develop seropositive disease with nodules and erosions on radiology.

Clinical manifestations

There are different patterns of clinical presentation of rheumatoid arthritis. The disease may present as a polyarticular arthritis with a gradual onset, intermittent or migratory joint involvement, or a monoarticular onset. In addition, extra-articular manifestations may be present (Box 53.1). Extra-articular features occur in approximately 75% of seropositive patients and are often associated with a poor prognosis.

Box 53.1 Examples of the extra-articular features of rheumatoid arthritis

Nodules; may be subcutaneous or within the lungs, eyes or heart

Pleural and pericardial effusions

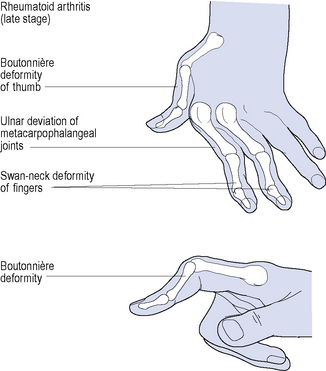

Disease onset is usually insidious with the predominant symptoms being pain, stiffness and swelling. Typically, the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the fingers, interphalangeal joints of the thumbs, the wrists, and metatarsophalangeal joints of the toes are affected during the early stages of the disease. Rheumatoid arthritis–associated deformities affecting multiple joints of the hands are shown in Fig. 53.1. Other joints of the upper and lower limbs, such as the elbows, shoulders and knees, are also affected. Morning stiffness may last for 30 min to several hours, and usually reflects the severity of joint inflammation. Up to one-third of patients also suffer from prominent myalgia, fatigue, low-grade fever, weight loss and depression at disease onset.

Diagnosis

Emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is extremely important to prevent disease activity, duration and ultimately joint destruction. The American Rheumatism Association (ARA) criteria (Box 53.2) were principally designed for disease classification in patients with established disease and are not sensitive for patients in the early stages of rheumatoid arthritis (Arnett et al., 1988). The Disease Activity Score using 28 joint counts (DAS28) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response are some of the tools used by rheumatologists to assess disease activity and to monitor the patient’s response to treatment (see Boxes 53.3 and 53.4).

Box 53.2 American Rheumatism Association criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis

The presence of at least 4 of these indicates a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis.

Box 53.3 Summary of DAS28 criteria in the assessment of rheumatoid arthritis

DAS28 is a composite formula. Four parameters are used to calculate a disease severity score:

Programmed calculators are used to determine the final DAS28.

High disease activity: DAS28 of >5.1

Moderate disease activity: DAS28 of >3.2 to 5.1

Low disease activity: DAS28 of 2.6–3.2

Box 53.4 American College of Rheumatology (ACR 20) response assessment in rheumatoid arthritis

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Treatment

There are four primary goals in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis:

Drug treatment

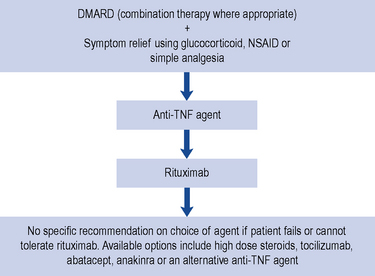

Guidance for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis has been issued and this is summarised in Fig. 53.2.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NSAIDs vary in their selectivity for the COX-1 and COX-2 isoforms, and are categorised as either non-selective NSAIDs or selective COX-2 inhibitors, otherwise known as the coxibs (Table 53.1). Non-selective NSAIDs generally block both COX-1 and COX-2, whereas the coxibs have higher selectivity for the COX-2 isoform. However, COX-2 selectivity in NSAIDs varies according to the dose of drug given, which is demonstrated by the dose-related toxicity exhibited by some agents such as ibuprofen. The three most commonly used non-selective NSAIDs have differing levels of COX-1 or COX-2 selectivity: diclofenac is COX-2 ‘preferential’, whereas ibuprofen and particularly naproxen preferentially inhibit COX-1. Originally, inhibition of COX-2 was thought to be involved solely with the anti-inflammatory, anti-pyretic and analgesic properties of NSAIDs. However, it is possible that COX-2 inhibition may also impair endothelial health, cause a prothrombotic state and promote cardiovascular disease.

Table 53.1 NSAIDs currently licensed in the UK

| Non-selective NSAIDs | COX-2 inhibitors |

|---|---|

| Aceclofenac | Celecoxib |

| Acemetacin | Etoricoxib |

| Azapropazone | |

| Dexibuprofen | |

| Dexketoprofen | |

| Diclofenac | |

| Etodolac | |

| Fenbufen | |

| Fluribprofen | |

| Ibuprofen | |

| Indometacin | |

| Ketoprofen | |

| Meloxicam | |

| Nabumetone | |

| Naproxen | |

| Piroxicam | |

| Tenoxicam | |

| Tiaprofenic acid |

Safety

At present, the exact cardiovascular risk for individual selective COX-2 inhibitors and NSAIDs is not known. Evidence from clinical trials of COX-2 inhibitors suggests that about 3 additional thrombotic events per 1000 patients/year may occur in the general population (MHRA, 2006).

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

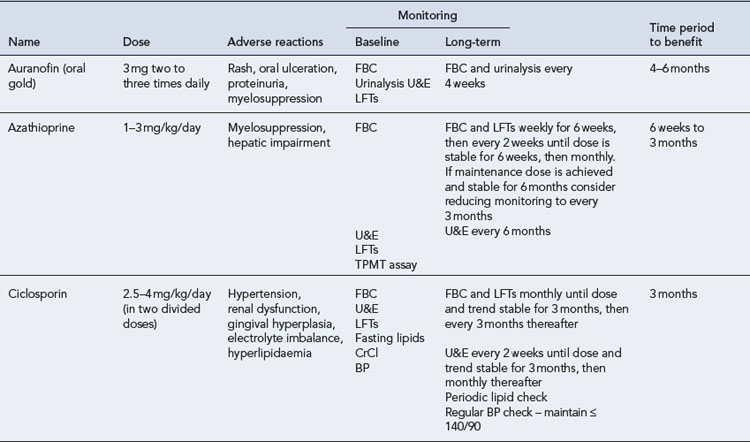

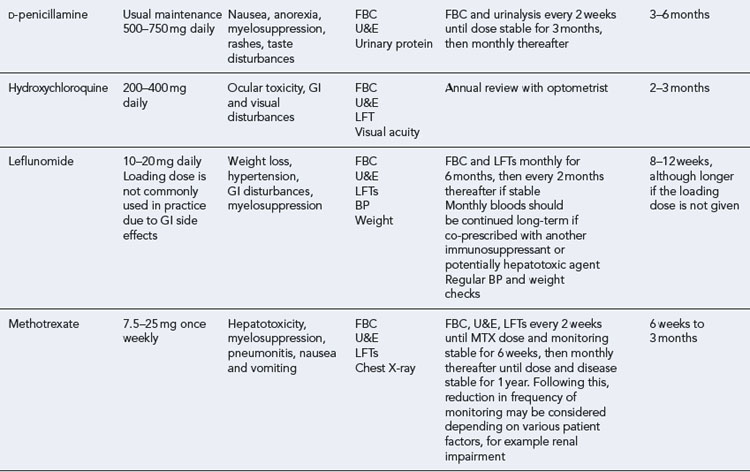

Joint damage is known to occur early in rheumatoid arthritis and is largely irreversible. The need for early intervention with DMARDs as part of an aggressive approach to minimise disease progression has become standard practice and is associated with better patient outcome. Early introduction of DMARDs also results in fewer adverse reactions and withdrawals from therapy (NCCCC, 2009).

The DMARDs that are commonly used for rheumatoid arthritis and have clear evidence of benefit are methotrexate, sulphasalazine, leflunomide and intramuscular gold (O’Dell, 2004). There is less compelling evidence for the use of hydroxychloroquine, d-penicillamine, oral gold, ciclosporin and azathioprine, although these agents do improve symptoms and some objective measures of inflammation. The exact mechanism of action of these drugs is unknown. All DMARDs inhibit the release or reduce the activity of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, interleukin-1, interleukin-2 and interleukin-6. Activated T-lymphocytes have been implicated in the inflammatory process, and these are inhibited by methotrexate, leflunomide and ciclosporin.

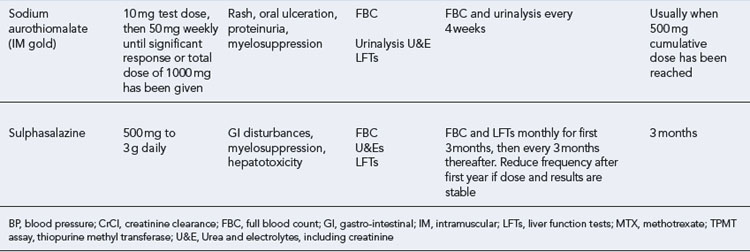

Patients should be made aware that the DMARDs all have a slow onset of action. They must be taken for at least 8 weeks before any clinical effect is apparent, and it may be months before an optimal response is achieved. Whilst early initiation of DMARDs is crucial, it is important to ensure the patient is maintained on therapy to maintain disease suppression. This itself is a challenge, due to the toxicity profiles of the majority of these drugs (see Table 53.2). The majority of the DMARDs require regular blood monitoring. Guidelines are available on the action to take in the event of abnormal blood results (Chakravarty et al., 2008).

Recommendations regarding the use of DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis are summarised in Box 53.5 (NCCCC, 2009

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree