Chapter 8 Respiratory System

Upper Respiratory Tract

Acute Inflammation

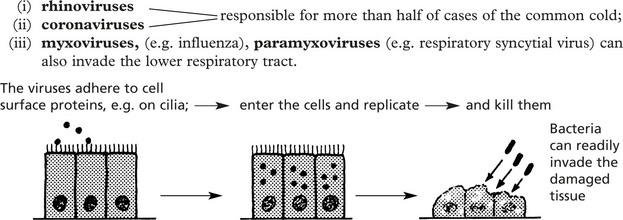

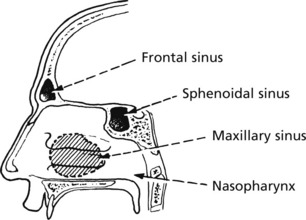

Infections of the nose, nasal sinuses, pharynx and larynx are common. They are usually mild and self-limiting. Most cases are due to viral infection, but this is often followed by bacterial superinfection.

The wide variety of different viruses involved prevents protective immunity.

Rhinitis

Common Cold (Acute Coryza)

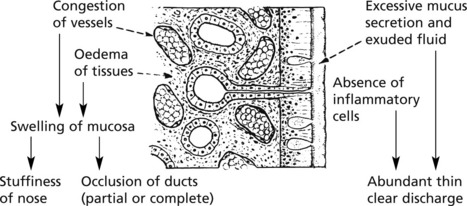

This common respiratory inflammation usually involves the nose and adjacent structures.

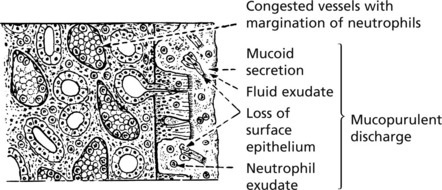

The 2 phases, viral and bacterial, are typically seen in this disease.

The infection is acquired by droplet spread of viruses by sneezing.

Allergic Rhinitis ‘Hay Fever’

An allergic (immediate type hyper-sensitivity) type of inflammation (2. p.101) is often seen. Patients develop immediate symptoms of sneezing, itching and watery rhinorrhoea.

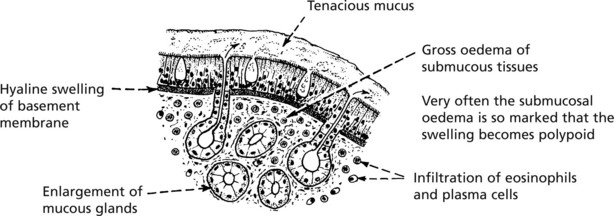

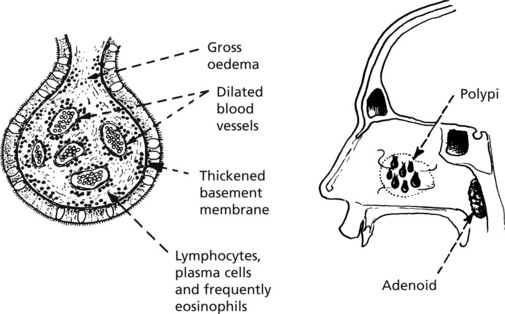

The repeated attacks frequently lead to chronic changes in the mucosa with polyp formation.

Nasal Polyps

These form particularly on the middle turbinate bones and within the maxillary sinuses.

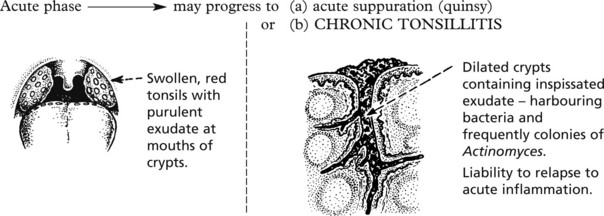

Acute Pharyngitis, Tracheitis and Laryngitis

Acute Pharyngitis and Tracheitis

Most sore throats are caused by viruses – including adenovirus and Epstein–Barr virus.

Bacteria include Streptococcus pyogenes, Haemophilus parainfluenzae and Corynbacterium diphtheriae.

Diphtheria, now uncommon in countries where vaccination is widespread, is a serious infection.

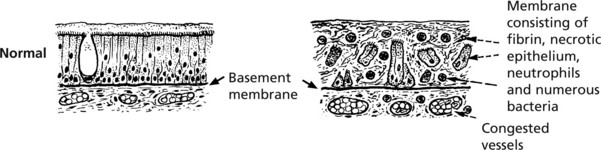

The formation of a pseudomembrane is striking.

This pseudomembrane may spread to block the larynx, causing respiratory obstruction.

The exotoxin of diphtheria is encoded by a bacteriophage (a virus which infects the bacterium). It can cause myocarditis (p.212) and neuropathy (p.569).

Acute laryngitis is often due to parainfluenza viruses. Acute oedema of the glottis is seen in some cases of anaphylaxis (p.101) and angioneurotic oedema.

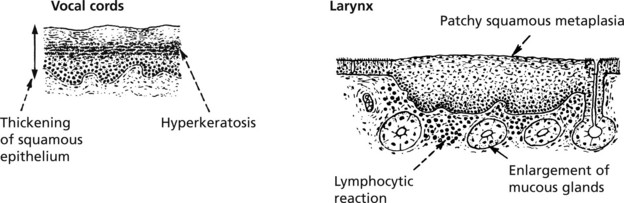

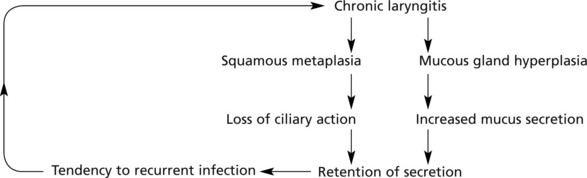

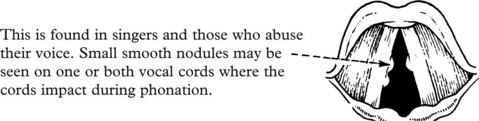

Other Disorders of the Larynx

Tumours of the Upper Respiratory Tract

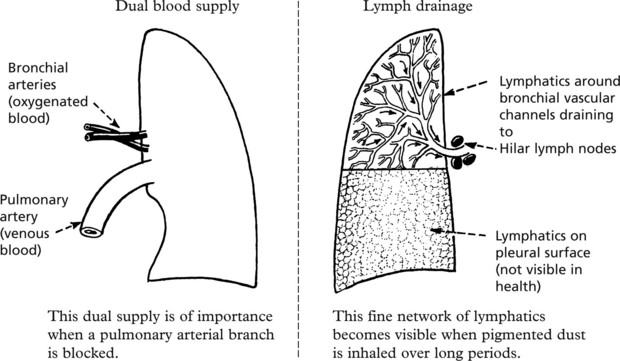

Lungs – Anatomy

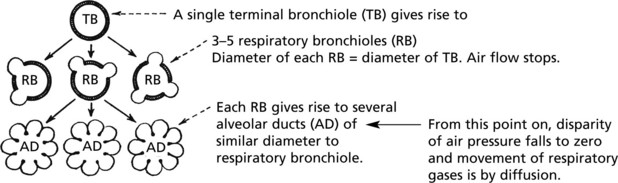

Acinus

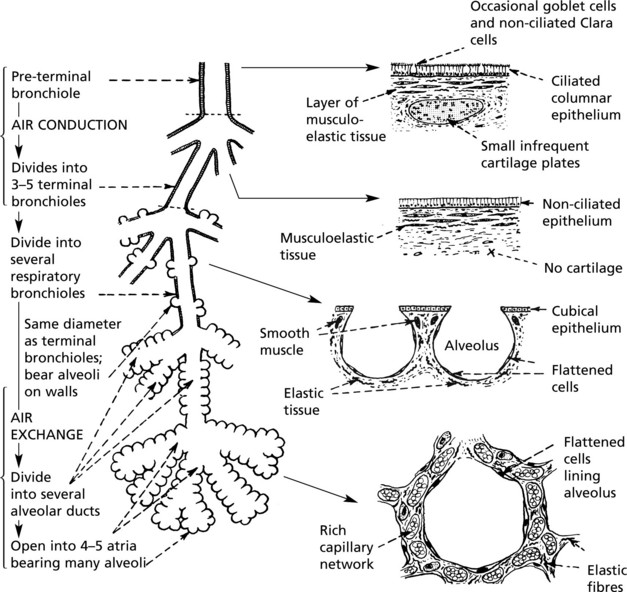

This is the functional unit of the lung, where gas transfer takes place. It consists of the respiratory bronchiole and associated alveolar ducts and sacs supplied by one terminal bronchiole. There are approximately 25 000 acini in the normal adult male lung.

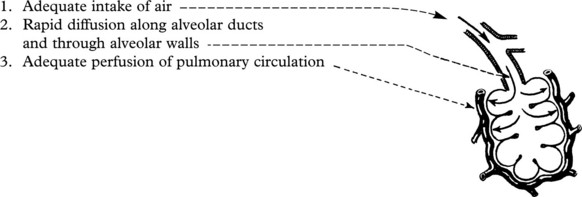

Respiration

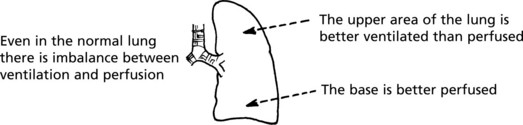

The normal intake of air is around 7 litres per minute; of this, after allowing for nonfunctioning dead space (trachea, bronchi, etc.), approximately 5 litres per minute are available for alveolar ventilation. A definite flow of air is maintained as far as the terminal bronchiole. Beyond this point the actual flow ceases and gas exchange is effected by diffusion.

Three factors are involved in the maintenance of adequate respiration:

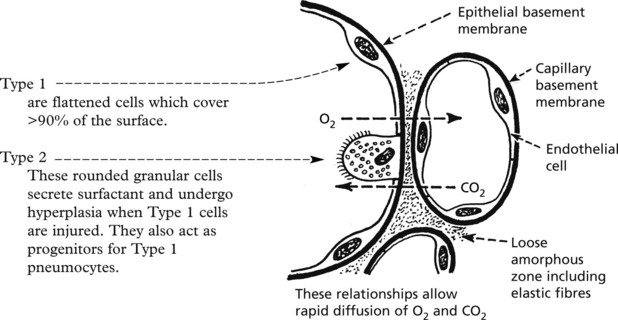

Impaired Diffusion of Gases

Three mechanisms may interfere with diffusion:

Altered Pulmonary Perfusion

Interference with the pulmonary circulation may occur in 4 main ways:

Note: In addition to hypoxaemia, inadequate perfusion tends to cause retention of carbon dioxide.

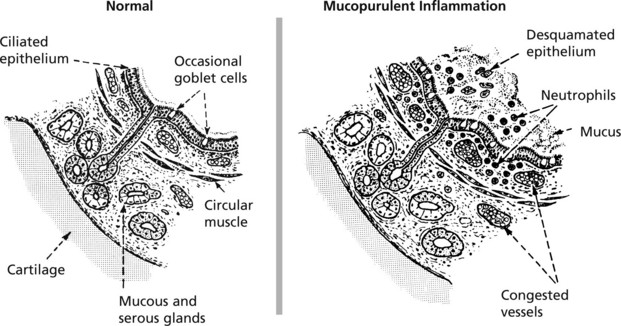

Acute Bronchitis

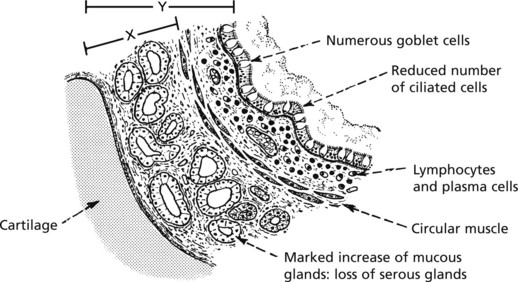

This is an inflammation of the large and medium bronchi. The condition may be serious if associated with pre-existing respiratory disease. Mucous and serous glands in the walls of the bronchi provide abundant mucoid secretion during the inflammation. Ciliated epithelia lining the bronchi aid passage of the exudate upward and help prevent spread down to the bronchioles.

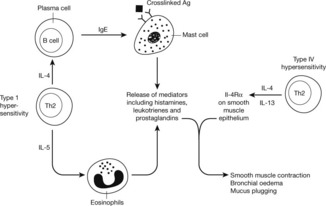

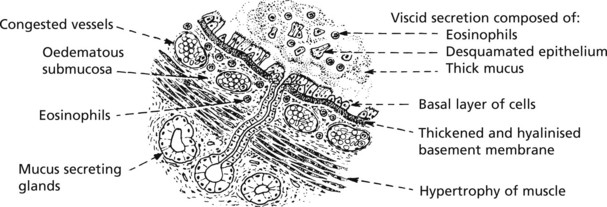

Bronchial Asthma

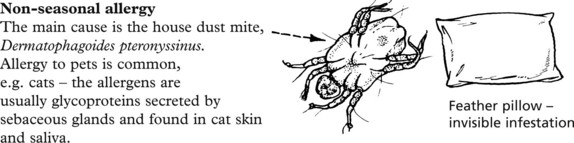

In asthma, there are spasmodic attacks of reversible bronchial obstruction with wheezing and dyspnoea and often a dry cough. The prevalence has markedly increased in recent years, although has now plateaued. There are 2 main patterns:

Other varieties include occupational asthma and aspirin-induced asthma.

The basic mechanism is as follows:

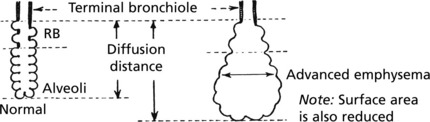

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

This term describes three entities that show considerable clinical overlap:

COPD is common and is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide.

Aetiology The main factors are:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree