11 Respiratory Disorders

Acute breathlessness

The systems involved would most probably be cardiac or respiratory. You go through the list in Box 11.1 (p. 346) as you walk to the ward.

Initial assessment

Then make a full cardiac and respiratory examination. Is there any evidence of DVT?

Upper airways obstruction

Diagnosis: Upper airways obstruction

Fortunately, the emergency crew recognised the problem and tried to clear the airway. There was no improvement so the Heimlich manoeuvre was performed and a large bone was expelled with immediate relief of the man’s respiratory distress. He was taken to A&E for assessment but discharged after 2 hours.

Remember

The Heimlich manoeuvre is used to expel an inhaled foreign body:

• Encircle the upper part of the abdomen, just below the patient’s rib cage, with your arms

• Give a sharp, forceful squeeze, forcing the diaphragm sharply into the thorax.

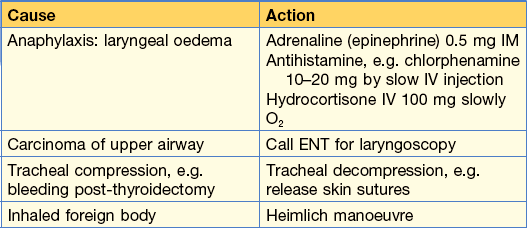

Other causes of upper airway obstruction are shown in Table 11.1, all of which require emergency management, which is also shown.

Cough

Acute cough

• Inhalation of direct irritants, e.g. smoke, chlorine gas, ozone and other air pollutants.

• In the asthmatic, inhalation of specific allergen, e.g. pollen or non-specific low-concentration irritants, e.g. perfume, tobacco fumes.

• Upper and lower respiratory tract infections (yellow/green sputum).

Chronic cough

• Large airway obstruction, e.g. carcinoma of bronchus or inhaled foreign body (Note: peanuts and other inhaled food will not be radio-dense).

• Persistent bronchial inflammation, e.g. asthma, bronchiectasis, COPD, smoking.

• Persistent infection, e.g. tuberculosis, lung abscess.

• Interstitial lung disease, e.g. pulmonary fibrosis, asbestosis.

• Raised left atrial pressure, e.g. mitral stenosis, left ventricular failure.

• Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GORD) and bulbar dysfunction.

Breathlessness and wheeze

Asthma causes breathlessness, cough and wheeze. However, all that wheezes is not asthma.

Differential diagnosis of asthma:

• Upper airway obstruction with stridor:

• Left ventricular failure (LVF):

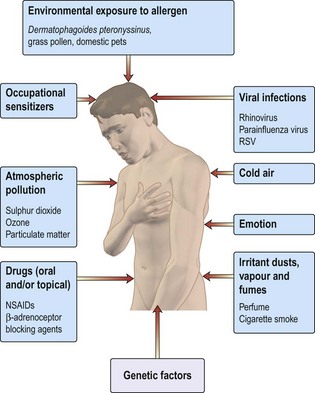

Figure 11.1 shows causes and triggers of asthma.

How would you manage this patient in A&E?

Immediate management should be:

• Reassurance that treatment will be effective

• Oxygen 40–60% (Keep SaO2 > 90%)

• Nebulised short acting β2 agonist (SAB), e.g. salbutamol 5 mg or terbutaline 10 mg) with oxygen. (NB only 10% of drug reaches the lungs)

• Arterial blood gases (ABGs):

• PEFR 4-hourly. Note: performing PEFR might be distressing for patient: do not demand unnecessary repeat testing

30 min later there has been no significant improvement in her breathlessness and PEFR. What would you do next?

• Continue with nebulised β2 agonist, now with added ipratropium (500 µg). Repeat every 30 min if necessary.

• Intravenous aminophylline infusion can be used if patient does not respond to repeated nebulisation with β2 agonist and ipratropium. However, do not use this if oral aminophylline has been taken.

There is now improvement in PEFR and breathlessness with nebulised β2 agonist and ipratropium. What treatment should be offered to her now?

Continuing management should be:

24–48 h before discharge

• Add inhaled corticosteroids, e.g. beclometasone, to oral steroids.

• Replace nebulised bronchodilators with inhalers.

• Introduce long-acting inhaled β2 agonists, e.g. salmeterol.

• Check inhaler technique (? might need spacer).

• Determine the cause of this attack (non-compliance, infection, allergen exposure).

Talk to asthma nurse

At discharge, patient should have:

• Oral and inhaled corticosteroids and long acting inhaled β2 agonist (LABA). SABAs can be used on an ‘as required’ basis.

Hyperventilation

Haemoptysis

Case history

Coughing up blood is a dramatic symptom and can be frightening to patients and their families.

Colour of blood – this can differ with different causes

• Pink frothy sputum: pulmonary oedema.

• Make sure it is not haematemesis, which would be suggested by:

Enquire about epistaxis, which may cause confusion. Blood-stained saliva suggests bleeding from gums.

Common conditions presenting with haemoptysis

Less common causes of haemoptysis are:

Management of this case

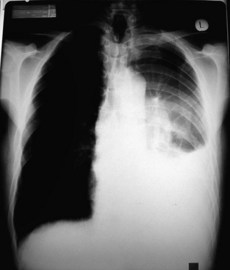

A chest X-ray was taken (Fig. 11.2 and Information box) which showed a pleural effusion and a hilar mass. The pleural effusion was aspirated and sent for cytology. A pleural biopsy was taken under ultrasound control and showed no evidence of malignancy on histology.

The patient was referred to the multidisciplinary team for discussion of treatment options.

Management of massive haemoptysis

• Monitor: oxygen saturation with oximetry, blood pressure and pulse rate.

• Perform CXR. Exclude coagulation defects.

• Endotracheal intubation and suction might be required.

• Urgent bronchoscopy by an experienced doctor is sometimes required.

• A cuffed tube can be employed to protect the unaffected lung. It is inserted into the bronchus via a bronchoscope.

• Bronchial artery embolisation is highly effective if the bleeding vessel can be identified.

Chest pain

• Exercise-induced central chest pain is usually cardiac in origin.

• Rest pain might be: cardiac, pleuritic, musculoskeletal, nerve root irritation, oesophageal, mediastinal or referred pain from abdomen.

• Lung diseases only cause pain if the pleura, mediastinum, intercostal nerves or bones are involved.

Is it cardiac pain?

Acute coronary syndrome

Pain at rest or on minimal exertion, sometimes very severe with sweating; pain persists.

Is it musculoskeletal?

• Muscles: Bornholm’s disease. Follows an upper respiratory tract infection; a low-grade fever can occur. Ache in muscles. Might be tender. Definite cases rare.

• Costochondral junction: Tietze’s disease; local pain on pressure over junctions. Responds to NSAIDs.

Respiratory failure

In respiratory failure arterial blood gas sampling is necessary to

• Identify type, i.e. alveolar hypo- or hyperventilation

• Appreciate the degree of compensation (i.e. the chronicity of the condition)

• A coexisting metabolic acidosis commonly causes confusion and can be recognised by the base excess value (see below).

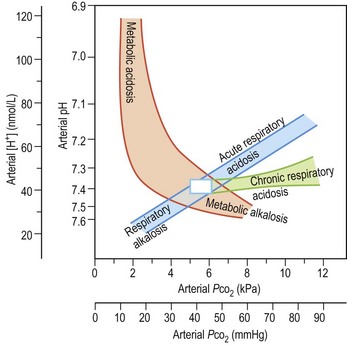

Summary of acid–base changes (Fig. 11.3)

In a respiratory acidosis

Examples: exacerbation of COPD, flail chest injury, Guillain–Barré syndrome.

Common ABG abnormalities

Life-threatening asthma

Supplemental O2 is being provided (note the high PaO2). There is a metabolic acidosis (note the pH and BE) as a result of metabolic demands exceeding O2 delivery and producing a lactic acidosis. Airflow limitation limits the normal respiratory compensation to this profound acidosis.

Acute or chronic respiratory failure in a patient with COPD

Acute or chronic respiratory acidosis exacerbated by a high FiO2 using variable performance mask (40–60% O2) (note high PaO2 and PaCO2). The high HCO3 results from renal compensation. The patient was changed to 28% oxygen.

Severe pneumonia (FiO2 60%)

Despite high FiO2 this patient is hypoxaemic because of ventilation: perfusion mismatch. The profound hypoxia despite oxygen and the associated metabolic acidosis indicate the need for urgent intubation and IPPV and are a reflection of circulatory failure resulting from septic shock.

How do I recognise impending respiratory arrest?

• Tachypnoea, respiratory rate > 30

• Sympathetic activation: pale and sweaty, agitation, confusion

• Progressive increase in PaCO2 or fall in PaO2

• Rapid desaturation on disconnection from O2, e.g. when drinking or coughing.

Evaluation is often at the ‘end of the bed’: is the patient getting tired? Be sensitive to subtle changes or a failure to improve.

Treating the cause

• Individual causes will require different actions: for instance, an intercostal drain for a tension pneumothorax or large pleural effusion (see p. 364).

• In neurological coma, intubation might be necessary for airway protection or to manage raised intracranial pressure by hyperventilation.

• Drug-induced respiratory failure can be confirmed by a therapeutic trial with a specific antidote, i.e. a bolus injection of naloxone for opiates and flumazanil for benzodiazepines. Infusions will be required if a positive response is obtained as antidotes have short half life.

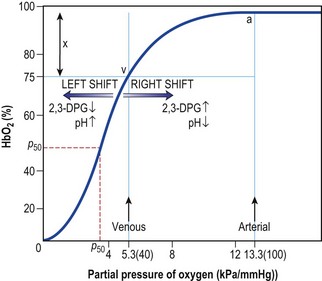

• Oxygen supplementation should be aimed at raising the PaO2 to beyond the steep part of the oxygen dissociation curve (Fig. 11.4). Very high PaO2 values are unnecessary but controlled O2 therapy via a fixed performance mask is only necessary in chronic respiratory failure resulting from COPD.

What do these blood gases mean?

The initial treatment in A&E was:

• Nebulised bronchodilators (salbutamol 5 mg nebulised + ipratropium bromide 500 µg).

• IV amoxicillin (erythromycin if patient penicillin allergic).

• IV steroids (this is conventional treatment but there is limited evidence for effectiveness). Hydrocortisone 100 mg × 3 daily.

• Encouragement to clear secretions including sitting patient up and the attention of the physiotherapist.

• CXR to exclude pneumothorax or demonstrate associated pneumonia.

Repeat ABGs were requested: pH 7.20, PaO2 6.5, PaCO2 12.5, HCO3 30.