Overview

A detailed occupational history is essential for the diagnosis of occupational respiratory disorders

Accurate diagnosis of the subset and cause of occupational asthma is essential for optimal management of the employee

Globally the incidence of pneumoconiosis and byssinosis is increasing as manufacturing industries are being established and/or outsourced to developing countries, where the standard of health and safety at work may be lower than in the developed world

Most occupational respiratory disorders can be prevented by reducing the exposure of employees to the causative agent

The sharp reduction in the incidence of asbestosis and pneumoconioses in industrialized countries during the past 70 years is attributable to a decline in manufacturing industries and higher health and safety standards. Asthma is now the most common occupational respiratory disorder in the developed world. By contrast, the traditional occupational lung diseases are commonly seen in developing countries, and occupational asthma is reported less often. However, the true prevalence of asthma attributable to occupation in these countries remains unknown.

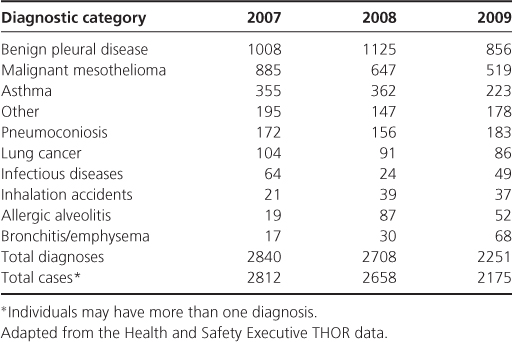

Since 1989, the understanding of the epidemiology of occupational lung disease in the United Kingdom has been greatly enhanced by the Surveillance of Work-related and Occupational Respiratory Disease (SWORD), which more recently has come under the umbrella of The Health and Occupation Reporting network (THOR) (Table 11.1). Occupational physicians, respiratory physicians and specially trained family doctors systematically report new cases of occupational lung diseases, together with the suspected agent, industry and occupation.

Table 11.1 Estimated number of new UK cases of work-related and occupational respiratory diseases reported by occupational and respiratory physicians to SWORD by diagnostic category 2007–2009

Work-Related Asthma

Work-related asthma (WRA) refers to asthma that is exacerbated or induced by inhalation exposures in the workplace. Occupational asthma is a subset of WRA and is defined as de novo asthma or recurrence of previously quiescent asthma induced by either (a) sensitization to a substance in the workplace (sensitizer-induced occupational asthma), or (b) exposure to an inhaled irritant at work (irritant-induced occupational asthma). Work-exacerbated asthma is another subset of WRA and is defined as pre-existing or concurrent asthma that is triggered by work-related exposures, for example irritants or exercise.

Sensitizer-induced asthma typically appears after a latent period of asymptomatic occupational exposure. Substances that induce occupational asthma (‘respiratory sensitizing agents) are classified as either of high (>10 kd) or low molecular weight (Table 11.2). High molecular weight substances are usually protein-derived allergens such as natural rubber latex and flour. They typically cause occupational asthma by immunoglobulin IgE antibody-associated mechanisms. In contrast, some low molecular weight chemicals, such as diisocyanates, act as haptens and combine with a body protein to form a complete antigen.

Table 11.2 Examples of high and low molecular weight substances, which may cause occupational asthma

| Substance | Occupational group at risk/industrial use |

| Low molecular weight chemicals | |

| Di-isocyanates | Car/coach paint spraying |

| Foam and plastic manufacture | Glues |

| Colophony (pine resin) | Electronics industry |

| Persulphate salts | Hairdressing |

| Complex platinum salts | Platinum refinery workers |

| Proteins (High molecular weight) | |

| Flour/grain | Bakers |

| Rodent urinary proteins | Laboratory workers |

| Salmon proteins | Fish processing plant workers |

| Natural rubber latex | Healthcare professionals |

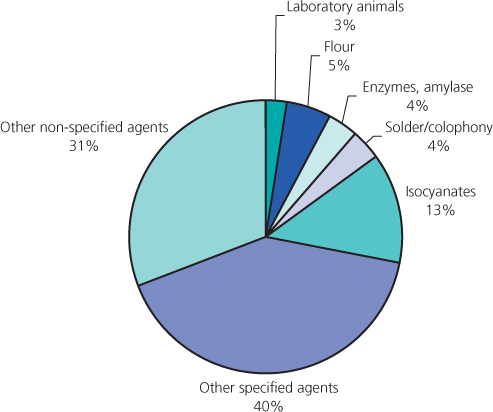

To date, more than 250 agents capable of causing immunological occupational asthma have been reported. Figure 11.1 illustrates the causes of occupational asthma reported by chest physicians and occupational physicians during 2007–2009 to THOR.

Figure 11.1 Occupational asthma: estimated number of diagnoses in which particular causative substances were identified.

In some jobs, such as farming, workers are exposed to many potential respiratory sensitizers and sensitization may occur through interaction of several agents including an array of potential sensitizers, such as animal-derived allergens, arthropods, moulds, plants and fungicides (Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 Farmers are at risk of developing occupational asthma because they are often exposed simultaneously to an array of potential sensitizers, such as animal-derived allergens, arthropods, moulds, plants and fungicides.

Atopic individuals are at increased risk of developing occupational asthma from high molecular weight allergens, but generally not from low molecular weight allergens. Tobacco smokers are at greater risk of developing asthma after occupational exposure to agents such as platinum salts and acid anhydride; the mechanism of this modifying effect is unknown. Tobacco smoking and atopy are common among the working population. These risk factors should not automatically exclude an individual from working with a respiratory sensitizer.

Occupational exposure to high levels of irritant fume—such as chlorine—usually occurs as the result of an industrial accident. Rarely this may induce an asthmatic response, described generally as ‘irritant-induced asthma’ but known formerly as reactive airways disease syndrome (RADS) (Box 11.1). The condition often resolves spontaneously but can persist indefinitely; it is characteristically resistant to standard asthma treatments.

- History of inhalation of gas, fume or vapour with irritant properties

- Rapid onset of asthma like symptoms after exposure

- Bronchial hyper-responsiveness present on metacholine (or similar) challenge test

- Individual previously free from respiratory symptoms

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree