9 Respiratory disease

Respiratory symptoms are the most common cause of presentation to the family practitioner. Asthma occurs in more than 10% of British adults, and bronchial carcinoma is the most common fatal malignancy in the developed world. The lung is the major site of opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients, and TB (including multiple drug-resistant strains) continues to increase, infecting one-third of the world’s population.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

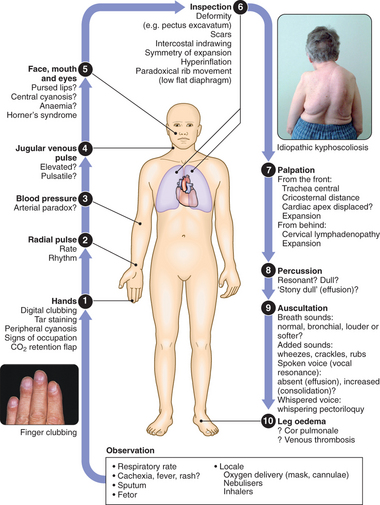

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

BREATHLESSNESS (DYSPNOEA)

CHRONIC EXERTIONAL DYSPNOEA

Pulmonary thromboembolism: Often presents with acute breathlessness with or without chest pain. However, chronic thromboembolic disease should be suspected in patients who present with more gradual onset of breathlessness, particularly if there is a previous history of thromboembolic events or marked exertional breathlessness but a relatively normal examination and CXR. Leg swelling and an elevated JVP may be present, but are non-specific.

CHEST PAIN

HAEMOPTYSIS

A clear history should be taken to establish that it is true haemoptysis and not haematemesis, gum bleeding or nosebleed. Haemoptysis must always be assumed to have a serious cause until proven otherwise. A history of repeated small haemoptyses, or blood-streaking of sputum, is highly suggestive of bronchial carcinoma. Fever, night sweats and weight loss suggest TB. Pneumococcal pneumonia is often the cause of ‘rusty’-coloured sputum but can cause frank haemoptysis, as can all the pneumonic infections which lead to suppuration or abscess formation. Bronchiectasis and intracavitary mycetoma can cause catastrophic bronchial haemorrhage and in these patients there may be a history of previous TB or pneumonia in early life. Pulmonary thromboembolism is a common cause of haemoptysis and should always be considered. Many episodes of haemoptysis are unexplained, even after full investigation, and are likely to be caused by simple bronchial infection.

THE SOLITARY RADIOGRAPHIC PULMONARY LESION

The incidental finding of a solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) on a plain CXR in an adult patient is a common dilemma and the differential diagnosis is broad (Box 9.2). Between 20 and 30% of all cancers present in this way; the incidence increases with age and accounts for >50% of nodules in patients aged >50 yrs.

Radiology

PLEURAL EFFUSION

The accumulation of fluid within the pleural space is termed pleural effusion. Accumulations of frank pus (empyema) or blood (haemothorax) represent separate conditions. Pleural fluid accumulates due either to increased hydrostatic pressure or decreased osmotic pressure (‘transudative effusion’ as seen in cardiac, liver or renal failure), or to increased microvascular permeability caused by disease of the pleural surface itself, or injury in the adjacent lung (‘exudative effusion’). Some causes of pleural effusion are shown in Box 9.3. Particular attention should be paid to a recent history of respiratory infection, the presence of heart, liver or renal disease, occupation (e.g. exposure to asbestos), contact with TB, and risk factors for thromboembolism.

Pleural aspiration and biopsy

Pleural aspiration reveals the colour and texture of fluid and on appearance alone may immediately suggest an empyema or chylothorax. The presence of blood is consistent with pulmonary infarction or malignancy, but may represent a traumatic tap. Biochemical analysis allows classification into transudate and exudate. An exudate usually has a protein concentration of >30 g/l or can be distinguished using Light’s criteria (Box 9.4). The predominant cell type provides useful information and cytological examination is essential. A low pH suggests infection but may also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis, ruptured oesophagus or advanced malignancy. In some clinical settings (e.g. left ventricular failure) it should not be necessary to sample fluid unless atypical features are present. Combining pleural aspiration with biopsy (using an Abrams needle) increases the diagnostic yield, but the best results are obtained from CT-guided biopsy or video-assisted thoracoscopy, allowing the operator to visualise the pleura and guide the biopsy directly.

SLEEP-DISORDERED BREATHING

THE SLEEP APNOEA/HYPOPNOEA SYNDROME (SAHS)

Clinical assessment

Investigations

Management

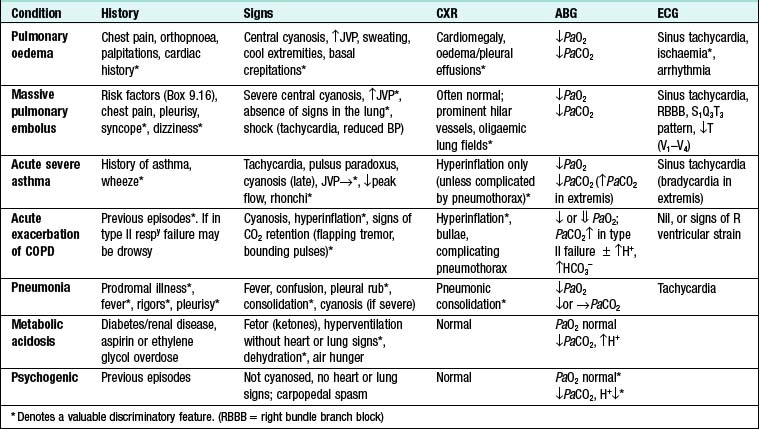

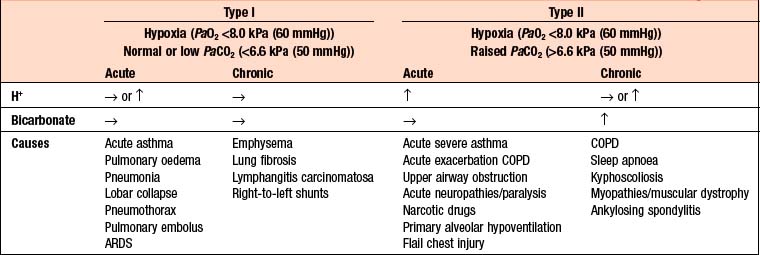

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

The term respiratory failure is used when pulmonary gas exchange fails to maintain normal arterial oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. Its classification into type I and type II relates to the absence or presence of hypercapnia (raised PaCO2). The main causes are shown in Box 9.5.

Management

The consequences of untreated severe hypoxaemia include:

CHRONIC AND ‘ACUTE ON CHRONIC’ TYPE II RESPIRATORY FAILURE

If controlled oxygen treatment causes a further increase in the PaCO2 associated with a reduction in pH, non-invasive or invasive ventilatory support is usually indicated. In these patients the decision regarding invasive ventilation can be particularly complex and difficult. Ideally, an early decision should be made, based on whether there is a potentially remediable precipitating condition and whether the patient is likely to regain an acceptable quality of life.

OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASES

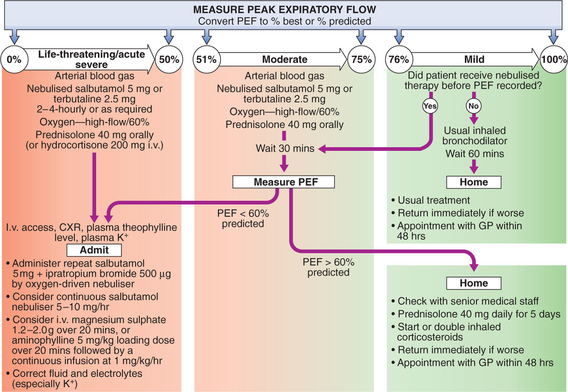

ASTHMA

Pharmacological treatment

Step 4—Poor control on a moderate dose of inhaled steroid and add-on therapy: The ICS dose may be increased to 2000 μg BDP or equivalent daily. A nasal corticosteroid should be used if upper airway symptoms are prominent. Consider trials of leukotriene receptor antagonists or theophyllines. Further studies on new therapies, such as monoclonal antibodies directed against IgE, are awaited.

Management of mild–moderate exacerbations

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE (COPD)

Clinical features

9.7 MODIFIED MRC DYSPNOEA SCALE ![]()

| Grade | Degree of breathlessness related to activities |

|---|---|

| 0 | No breathlessness except with strenuous exercise |

| 1 | Breathlessness when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill |

| 2 | Walks slower than contemporaries on level ground because of breathlessness or has to stop for breath when walking at own pace |

| 3 | Stops for breath after walking about 100 m or after a few mins on level ground |

| 4 | Too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing or undressing |

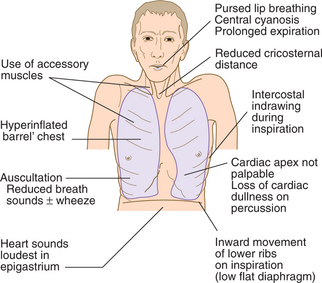

Two classical phenotypes have been described:

Investigations

Management and prognosis

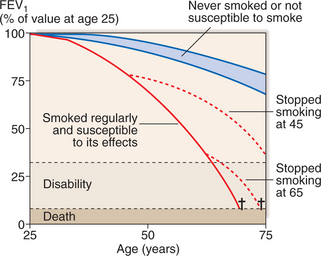

Smoking cessation: Offer help to stop smoking at every opportunity. Combine pharmacotherapy with appropriate support as part of a programme. It is the only intervention proven to decelerate the decline in FEV1 (Fig. 9.3).

Pulmonary rehabilitation: Encourage exercise. Multidisciplinary programmes (usually 6–12 wks’ duration) incorporating physical training, education and nutritional counselling reduce symptoms, improve health status and enhance confidence.

Other measures: Influenza vaccination; pneumococcal vaccination; trial of mucolytic therapy.

Acute exacerbations of COPD

Oxygen therapy: High concentrations of oxygen may cause respiratory depression and worsening acidosis (p. 280). Controlled oxygen at 24% or 28% should be used, aiming for PaO2 >8 kPa (60 mmHg) (or an SaO2 >90%) without worsening acidosis.

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV): If patients have persistent tachypnoea and a respiratory acidosis (H+ ≥ 45/pH < 7.35), NIV is associated with reduced requirements for mechanical ventilation and reductions in mortality. Consider mechanical ventilation where there is a reversible cause for deterioration (e.g. pneumonia), or if there is no prior history of respiratory failure.

BRONCHIECTASIS

Bronchiectasis is defined as abnormal dilatation of the bronchi due to chronic airway inflammation and infection. It is usually acquired, but may result from an underlying genetic or congenital defect of airway defences (Box 9.8).

Investigations

Radiology: CXR may be normal in mild disease. In advanced disease, thickened airway walls, cystic bronchiectatic spaces, and associated areas of pneumonic consolidation or collapse may be seen. CT is much more sensitive, and shows thickened dilated airways.

Assessment of ciliary function: Saccharin test or nasal biopsy may be used.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree