13 Respiratory disease

Approach to the patient

For management of a massive haemoptysis, see Box 13.1.

Box 13.1 Management of massive haemoptysis

Shortness of breath

Most people get breathless on exertion; exercise tolerance should be documented. Breathlessness can be of sudden onset, e.g. in acute left ventricular failure, or more progressive, as in COPD. It may vary at different times of the day, e.g. in asthma it is usually worse in the morning.

Breathlessness on lying flat occurs in, for example, pulmonary oedema (p. 425). Breathlessness with a wheeze occurring on exposure to an allergen is seen in asthma (e.g. horse riding). It can occur many hours after exposure to an allergen (p. 520) in, for example, hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Inhalation of foreign bodies can cause choking and acute shortage of breath. Treatment is with the Heimlich manoeuvre. See Emergencies in Medicine p. 714.

Chest pain

Chest pain in respiratory disease is usually pleuritic. Pain can be due to other causes, e.g. localized pain in costochondritis. Shoulder tip pain suggests irritation of the diaphragmatic pleura. Retrosternal soreness occurs with tracheitis but also in other conditions, e.g. oesophagitis, when it is usually burning. Chest pain should always be differentiated from cardiac pain, which is usually a central crushing chest pain radiating to the jaw, neck and left arm (p. 431).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

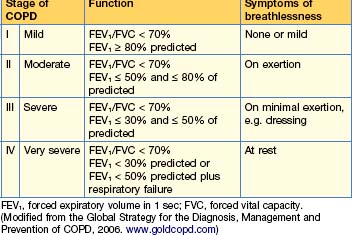

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a slowly progressive condition predominantly caused by smoking and is the sixth commonest cause of death worldwide; its incidence is increasing. It is characterized by airflow limitation, which is not fully reversible. The lungs have an abnormal inflammatory response to inhaled particles or gases, resulting in airflow limitation. The GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, WHO) criteria for the diagnosis of lung disease are shown in Table 13.1.

Pathogenesis

Clinical features

COPD is suspected on the basis of chronic progressive symptoms, usually with a smoking history of more than 20 pack years (1 pack year = 20 cigarettes per day for 1 year). It is supported by objective evidence of airflow limitation (or obstruction), usually with spirometry, which does not return to normal with treatment.

Signs

Diagnosis and investigations

Lung function tests

Other tests

Management

Smoking cessation

Drug therapy

Bronchodilator therapy

Side-effects include fine tremor, nervous tension, tachycardia, arrhythmias and hypokalaemia.

In mild disease short-acting β2 agonists or short-acting antimuscarinic bronchodilators should be prescribed as required. Their effects are additive and once airflow becomes more severe a regular antimuscarinic can be added to a β agonist. Some patients prefer to use just one combined inhaler ipratropium bromide 20 mcg and salbutamol 100 mcg/metered dose 2 puffs 4 times a day.

Corticosteroids

There are many side-effects associated with corticosteroids (see Box 15.2, p. 585). Inhaled steroids cause considerably fewer systemic side-effects, although at high doses adverse effects have been reported.

Combination therapy

Oxygen therapy

The following patients should be assessed for oxygen therapy:

Patients fulfil the criteria for LTOT when they have:

Guidelines for domiciliary oxygen are shown in Box 13.2.

Box 13.2 Guidelines for domiciliary oxygen (Royal College of Physicians, 1999)

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV)

This is mainly used for exacerbations of COPD — see p. 485. The ventilators are small and can be used at home. Patients should be considered for home NIV if, despite maximal treatment, they have hypercapnic respiratory failure and have required ventilatory support during an exacerbation, or are acidotic or hypercapnic on LTOT.

Diuretic therapy (p. 420)

This is necessary for all oedematous patients. Patients should be weighed daily.

Other agents

• Antibiotics

• Vaccination/antiviral therapy

Non-pharmacological interventions

Acute exacerbations of COPD (type II respiratory failure)

Investigations

Treatment

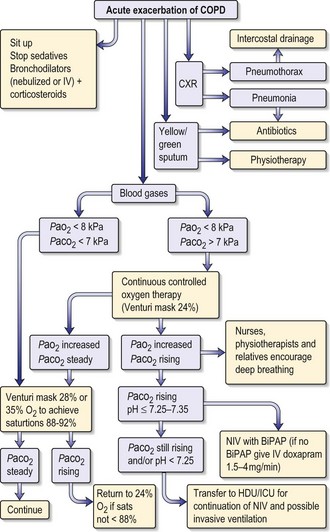

The treatment of respiratory failure in COPD is shown in Fig. 13.1. General care includes prophylaxis against deep vein thrombosis, optimizing fluid status and ensuring adequate nutrition.

• Non-invasive ventilation (NIV)

A tight-fitting facial mask delivers bi-level positive airway pressure ventilatory support (BiPAP). Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP, p. 542) is also used. NIV can avoid the need for endotracheal intubation.

Prognosis of COPD

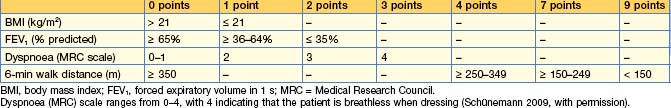

The predictors of a poor prognosis are increasing age and worsening airflow limitation, i.e. a fall in FEV1. A predictive index (BODE = body mass index, degree of airflow obstruction, dyspnoea and exercise capacity) has recently been modified, improving prediction of outcome, and is shown in Table 13.2. A patient with a BODE index of 0–2 has a mortality rate of 10% and with 7–10 it rises to 80% at 4 years. A simpler index using age, dyspnoea and airflow obstruction (ADO) gives a similar prognosis.

Discharge planning

Obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome

Investigations

Sleep studies

Treatment

Behavioural interventions

Treatment of underlying conditions such as hypothyroidism may greatly improve symptoms of OSAHS.

Non-surgical interventions

• NIV

Surgery

Cystic fibrosis

Genetics

Pathophysiology

Clinical features

Respiratory

Gastrointestinal

About 85% of patients have pancreatic insufficiency from birth, resulting in malabsorption of fat and protein, and causing steatorrhoea and malnutrition. Infants and children may present with failure to thrive, diarrhoea or acute pancreatitis. Bowel obstruction secondary to meconium ileus (10%) can occur soon after birth; if it occurs later in life, it is known as ‘meconium ileus equivalent’ or ‘distal intestinal obstructive syndrome’ (DIOS). These patients present with volvulus or rectal prolapse. Biliary obstruction may result in cholecystitis, while chronic liver disease and cirrhosis can lead to portal hypertension, varices and splenomegaly. There is an increased prevalence of gallstones (especially cholesterol), reflux oesophagitis, peptic ulceration and gastrointestinal malignancy in CF.

Diagnosis and investigations

• Positive family history.

Treatment

Antibiotics

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree