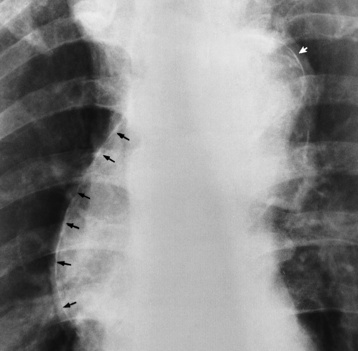

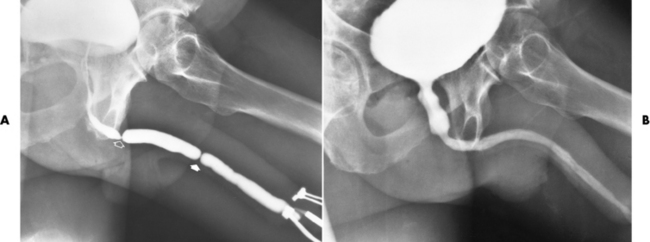

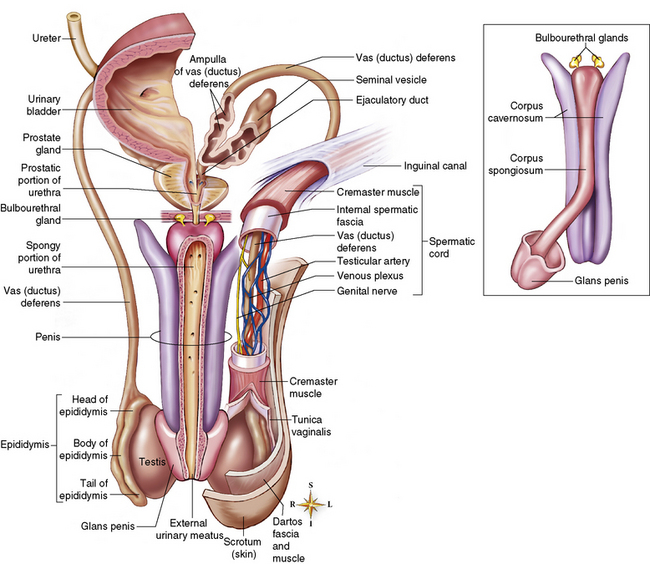

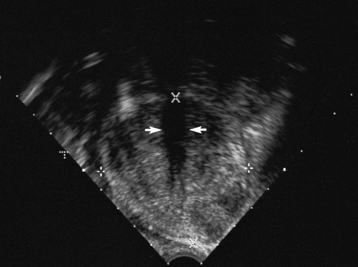

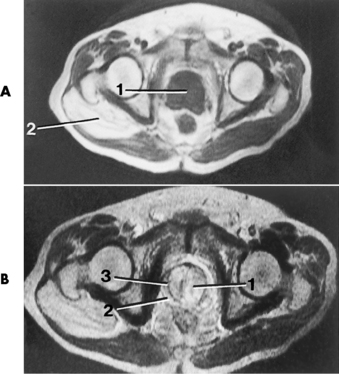

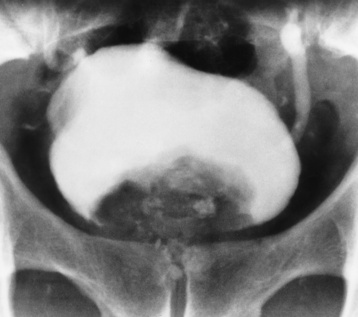

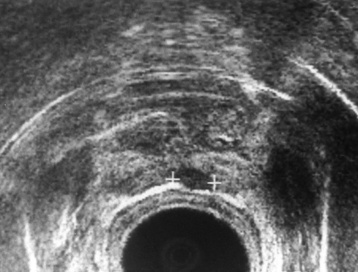

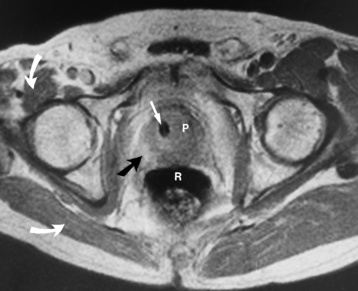

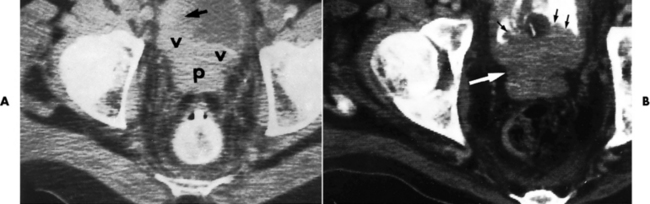

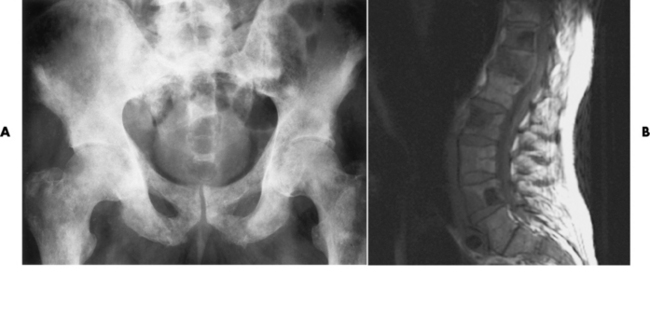

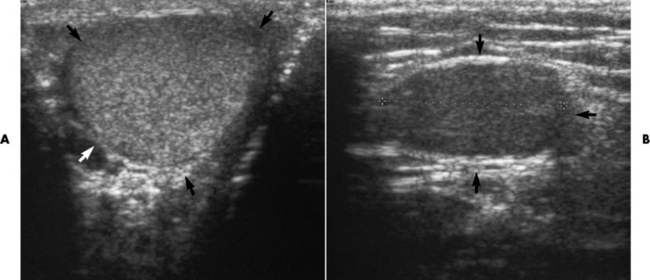

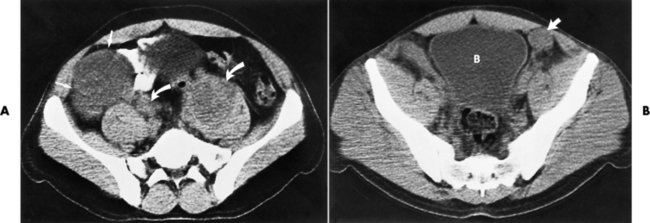

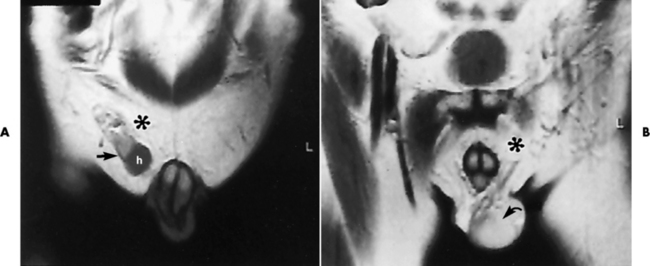

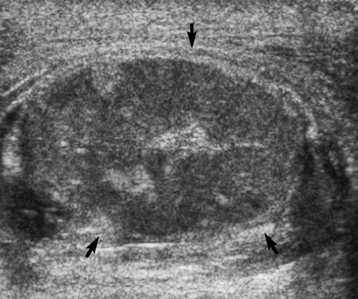

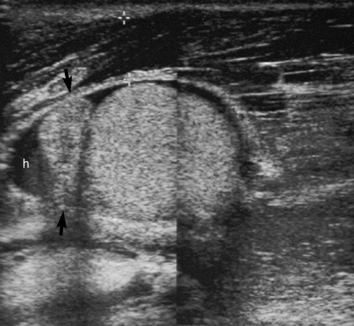

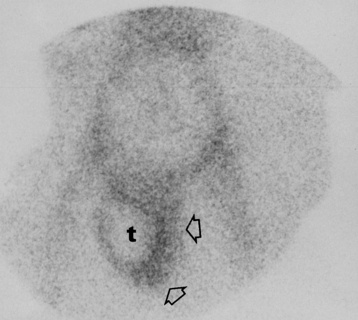

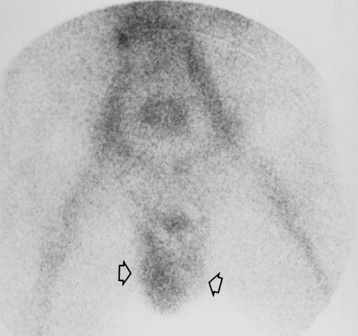

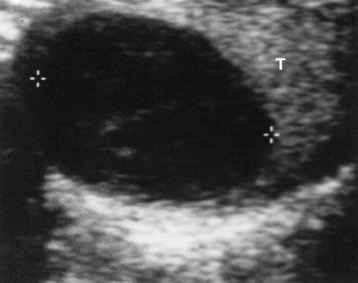

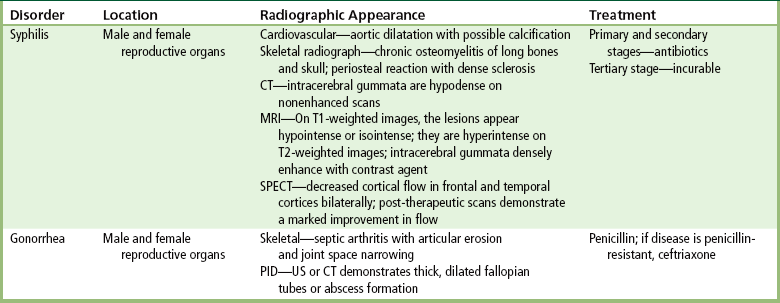

Chapter 11 After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1 Define and describe all bold-faced terms in this chapter 2 Describe the physiology of the reproductive system 3 Identify anatomic structures on both diagrams and radiographs of the reproductive system 4 Differentiate various pathologic conditions affecting the reproductive system and their radiographic manifestations 5 Initiate alterations that must be made in routine exposure techniques to obtain optimal-quality radiographs Syphilis is a chronic, sexually transmitted systemic infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. The baby of an infected mother may be born with congenital syphilis. In the primary stage of infection, a chancre, or ulceration, develops on the genitals (usually the vulva of the female and the penis of the male). If untreated, the secondary stage of the disease appears as a nonitching rash that affects any part of the body. At this stage, the patient is still infectious. If still untreated, the disease may become dormant for many years before the development of the most serious or tertiary stage of the disease, in which radiographic abnormalities become apparent. The young black male population is most often affected. Cardiovascular syphilis involves primarily the ascending aorta, which may become aneurysmally dilated and often demonstrates linear calcification of the wall (Figure 11-1). Syphilitic aortitis often involves the aortic valvular ring and produces aortic regurgitation with enlargement of the left ventricle. Syphilitic involvement of the skeletal system most commonly produces radiographic findings of chronic osteomyelitis, which usually affects the long bones and the skull. The destruction of bone incites a prominent periosteal reaction, with dense sclerosis as the most outstanding feature (Figure 11-2). Syphilis is a major cause of neuropathic joint disease (Charcot’s joint), in which bone resorption and total disorganization of the joint are associated with calcific and bony debris (Figure 11-3). Figure 11-3 Neuropathic joint disease in syphilis. Joint fragmentation, sclerosis, and calcific debris about the hip. Multiple bone abnormalities can occur in infants with congenital syphilis who are born to infected mothers (Figure 11-4). Mental retardation, deafness, and blindness are common complications. Summary of Findings for Infectious Diseases of the Reproductive System GI, gastrointestinal; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; US, ultrasound. days after infection. An acute urethritis with copious discharge of pus develops in men. Women may be asymptomatic or may have minimal symptoms of urethral or cervical inflammation. If untreated, the inflammation may become chronic, spread upward, and produce fibrosis, leading to urethral stricture in men (Figure 11-5) and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or sterility in women. A serious complication is fibrous scarring of the fallopian tubes that may result in sterility or an ectopic pregnancy. Physiology of the male reproductive system The major function of the male reproductive system is the formation of sperm (spermatogenesis), which begins at about 13 years of age and continues throughout life. Under the influence of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secreted by the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, the seminiferous tubules of the testes are stimulated to produce the male germ cells called spermatozoa. In addition to producing sperm cells, the testes secrete the male hormone testosterone. This substance stimulates the development and activity of the accessory sex organs (prostate, seminal vesicles) and is responsible for adult male sexual behavior. Testosterone causes the typical male changes that occur at puberty, including the development of facial and body hair and alterations in the larynx that result in a deepened voice. Testosterone also helps regulate metabolism by promoting growth of skeletal muscles and is thus responsible for the greater muscular development and strength in males. The final maturation of sperm occurs in the epididymis, a tightly coiled tube enclosed in a fibrous casing (Figure 11-6). The sperm spend about 1 to 3 weeks in this segment of the duct system, where they become motile and capable of fertilizing an ovum. The tail of the epididymis leads into the vas deferens, a muscular tube that passes through the inguinal canal as part of the spermatic cord and joins the duct from the seminal vesicle to form the ejaculatory duct. Depending on the degree of sexual activity and frequency of ejaculation, sperm may remain in the vas deferens up to 1 month with no loss of fertility. Severing of the vas deferens (vasectomy) is an operation performed to make a man sterile. Vasectomy interrupts the route from the epididymis to the remainder of the genital tract. The prostate gland lies just below the bladder and surrounds the urethra. It secretes a thin alkaline substance that constitutes the major portion of the seminal fluid volume. The alkalinity of this material is essential to sperm motility, which would otherwise be inhibited by the highly acidic vaginal secretions. Transrectal ultrasound imaging, performed by means of a probe inserted into the rectum, demonstrates gland enlargement and heterogeneous signal intensity of the central portion (Figure 11-7). A circumferential surgical pseudocapsule, discrete nodules, and a thickened bladder wall may also be visualized. Moreover, an abdominal-pelvic scan can demonstrate residual urine volume and aids in the evaluation of the kidneys for the presence of hydronephrosis. On excretory urography, the enlarged prostate typically produces elevation and a smooth impression on the floor of the contrast material–filled bladder (Figure 11-8). Elevation of the insertion of the ureters on the trigone of the bladder produces a characteristic J-shaped, or fish-hook, appearance of the distal ureters. Residual urine in the bladder provides a growth medium for bacterial infection, which produces cystitis; the infection may ascend from the bladder to the kidney, resulting in pyelonephritis. On MR images, benign prostatic hyperplasia causes a diffuse or nodular area of homogeneous low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and an inhomogeneous, mixed (intermediate to high) signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Figure 11-9). A pseudocapsule, representing compression of adjacent tissue visualized as a low–signal intensity rim, often accentuates focal enlargement. Diffuse enlargement shows similar intensity changes, though the pseudocapsule is not present. Unfortunately, the intensity of benign prostatic hyperplasia may often be similar to that of the normal prostate or a region of prostatitis. Radiographically, carcinoma of the prostate often elevates and impresses the floor of the contrast-filled bladder. Unlike the smooth contour seen in benign prostatic hyperplasia, the impression on the bladder floor is usually more irregular in carcinoma (Figure 11-10). Bladder neck obstruction, infiltration of the trigone, or invasive obstruction of the ureters above the bladder may produce obstruction of the upper urinary tract. Transrectal ultrasound is the preferred technique for detecting carcinoma of the prostate (Figure 11-11). The normal prostate has a generally homogeneous appearance with a moderate echo pattern. Early studies indicated that prostatic carcinoma appeared as hyperechoic areas. However, with the development of newer and higher-frequency transducers, many carcinomas appear as areas of low echogenicity within the prostate. Up to 40% of carcinomas are isoechoic with normal prostate tissue and thus cannot be visualized on ultrasound. The latest studies have concluded that the wide range of sonographic patterns in carcinoma indicates that ultrasound cannot reliably differentiate prostatic malignancy from benign disease. MRI can superbly delineate the prostate, seminal vesicles, and surrounding organs to provide accurate staging of pelvic neoplasms. When the spin-echo technique is used, the central and peripheral zones of the prostate are well demonstrated and distinctly separate from the surrounding levator ani muscles. In the sagittal plane, the relation of the prostate to the bladder, rectum, and seminal vesicles is clearly shown. Prostatic carcinoma is best demonstrated on long TR images, where it appears as disruption of the normally uniform high signal intensity of the peripheral zone of the prostate (Figure 11-12). T2-weighted images demonstrate low intensity that is surrounded by the hyperintense signal of the normal tissue. The new technique of MR lymphography aids in visualizing nonenlarged pelvic lymph nodes. However, there is much controversy over whether MRI is reliable for detection and diagnosis of prostate cancer, and therefore a precise diagnosis requires a biopsy and histologic examination. Research findings state that the demonstration of a normal-appearing prostate gland on MRI does not exclude the presence of a neoplasm. In addition, inhomogeneity of the gland is a common nonspecific finding that can also be seen in patients with adenoma or prostatitis. Carcinoma of the prostate may spread by direct extension or by way of the lymphatics or the bloodstream. Spread of carcinoma of the prostate to the rectum can produce a large, smooth, concave pressure defect; a fungating ulcerated mass simulating primary rectal carcinoma; or a long, asymmetrical annular stricture. Both ultrasound and CT, especially the arterial phase of multislice CT, aid in defining extension of tumor into the bladder and seminal vesicles and in detecting metastases in enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 11-13). The most common hematogenous metastases are to bone. They involve primarily the pelvis, thoracolumbar spine, femurs, and ribs. These lesions are most commonly osteoblastic and appear as multiple rounded foci of sclerotic density (Figure 11-14) or occasionally as diffuse sclerosis involving an entire bone (“ivory vertebra”). Patients with bony metastases usually have strikingly elevated serum acid phosphatase values. Because significant bone destruction or bone reaction must occur before a lesion can be detected on plain radiographs, the radionuclide bone scan is the best screening technique for detection of asymptomatic skeletal metastases in patients with carcinoma of the prostate. However, because the radionuclide scan is very sensitive but not specific and may show increased uptake in multiple disorders of the bone, conventional radiography of the affected site should be performed when the scan is abnormal. In the absence of a palpable testicle, ultrasound is usually used as a screening technique. This modality carries no radiation risk and has a high diagnostic accuracy in demonstrating undescended testicles that are located in the inguinal canal (Figure 11-15). However, sonography is not successful in detecting ectopic testicles in the pelvis or abdomen. If ultrasound fails to demonstrate an undescended testis, MRI or CT is indicated (Figures 11-16 and 11-17). MRI typically demonstrates a low signal mass on T1-weighted images that has high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. The uniform oval soft tissue mass of an undescended testis demonstrates contrast enhancement on CT. The preferred imaging modality for testicular torsion or epididymitis depends on the patient’s age—generally, color Doppler ultrasound in adults and radionuclide studies in children. As new technology improves color and power, Doppler ultrasound is the modality of choice in most cases. Doppler ultrasound demonstrates the presence of intratesticular arterial pulsations. In testicular torsion, the arterial perfusion is diminished or absent (Figures 11-18 and 11-19), whereas in epididymitis there is increased blood flow (Figure 11-20). Similarly, the radionuclide angiogram shows isotope activity on the twisted side that is either slightly decreased or at the normal, barely perceptible level. On the uninvolved side, the perfusion should be normal. When compared with the decreased activity on the involved side, the perfusion appears to be increased. Static nuclear scans demonstrate a rounded, cold area replacing the testicle in patients with torsion (Figure 11-21), but a hot area in those with epididymitis (Figure 11-22). A nuclear testicular scan is superior to Doppler ultrasound for distinguishing between testicular torsion and epididymitis. Testicular tumors are best diagnosed on ultrasound examination (with 98% to 100% accuracy). The normal testis has a homogeneous, medium-level echogenicity. A localized testicular tumor appears as a circumscribed mass with either increased or decreased echogenicity in an otherwise uniform-echo testicular structure. Seminomas appear as uniform hypoechoic masses without calcification or cystic areas (Figure 11-23). A teratoma appears inhomogeneous with cystic and solid areas of calcification and cartilage (Figure 11-24). Testicular tumors can also be detected on MRI (Figure 11-25), which is required when ultrasound findings are equivocal or when there is discrepancy between the ultrasound findings and the physical examination.

Reproductive System

Infectious diseases of both genders

Radiographic Appearance

Gonorrhea

Male reproductive system

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Radiographic Appearance

Carcinoma of the prostate gland

Radiographic Appearance

Staging

Undescended testis (cryptorchidism)

Radiographic Appearance

Testicular torsion and epididymitis

Radiographic Appearance

Testicular tumors

Radiographic Appearance

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Reproductive System