The term head and neck cancer (HNC) refers to a myriad of malignant diseases of the head and neck, including not only cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract but also cancers of the skin, salivary glands, thyroid gland, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, bone, and cartilage, and metastatic tumors from other body sites. However, in general usage it is most commonly used to describe squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx. This chapter focuses on the treatment and rehabilitation of the aforementioned patients but the principles and techniques described can be easily extrapolated to the treatment of patients with less common tumors of the head and neck.

The dominant histology of HNC is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which comprises more than 80% of cases in the United States. While the overall incidence of HNC has remained stable over the last several decades, there have been changes in the incidence of cancer in certain sites. Incidence has risen for the oral cavity, oropharynx, and thyroid gland, and fallen for the hypopharynx and larynx. Currently, it is estimated that there will be more than 40,000 new cases of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx in the U.S. each year. 1 The mortality has fallen during the same time frame for cancer at all sites except thyroid cancer, for which the mortality rate has remained stable. 2 The rising incidence of thyroid cancer has been ascribed to an increase in diagnosis of previously undetected thyroid cancers but this proposition is not universally accepted. 3

SCC of the head and neck has traditionally been associated with the use of tobacco and alcohol. Those who both smoke and drink have a greatly increased risk of developing SCC of the head and neck, which suggests that the two activities act synergistically to promote the development of cancer. 4 However, a subset of perhaps 20% of patients lack the typical risk factors for head and neck SCC. Recent discoveries have indicated that infection with high-risk types of human papilloma virus (HPV) is an independent risk factor for the development of SCC of the head and neck, particularly in the tonsil and base of the tongue. 5, 6 Recent studies have found an increasing incidence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers in white men and women. 1 There is good evidence that some patients whose tumor is caused by HPV may have a better prognosis, and in the future the treatment of patients may, in part, be determined by their HPV status, but it is not yet certain whether this is possible and, if possible, what changes will result. 7

The diagnosis of HNC represents a tremendous burden to the patient. Both the tumor itself and the treatment needed to address it result in problems affecting numerous domains of human functioning. The head and neck are vital not only for life but also for how we generally interact with society. Treatment can affect not only the ability to eat and speak, but also sight, hearing, sense of smell, and appearance. Generally, treatment choices are based upon what is most likely to maximize survival as well as on the potential loss of function that a treatment option may cause. There is substantial evidence demonstrating that not only does treatment for HNC affect quality of life across multiple domains, but also quality of life can be substantially improved by vigorous efforts at rehabilitation. 8 Therefore, the provision of rehabilitation services to patients with HNC is crucial. These services allow patients to recover from deficits caused by treatment, and they may allow the use of treatment choices that are more effective at curing the patient’s cancer but would not be considered if adequate rehabilitation services were not available.

13.2 Head and Neck Cancer Symptoms and Presentation

HNC can present with a variety of symptoms. The presenting complaint may often differ depending on the location of the tumor. The most common presenting complaint in patients with cancers of the oral cavity is simply a sore that will not heal. Minor trauma to the oral cavity is common. We have all had the experience of inadvertently biting our tongue or cheek. The oral mucosa generally heals quickly; therefore, the presence of a lesion in the mouth that does not heal within 2 weeks should raise concern. Other common complaints include loose or painful teeth, ill-fitting dentures, bleeding from the mouth, ear pain, or a neck mass. Unfortunately, a substantial number of patients will not heed these early signs of cancer and will present with advanced tumors.

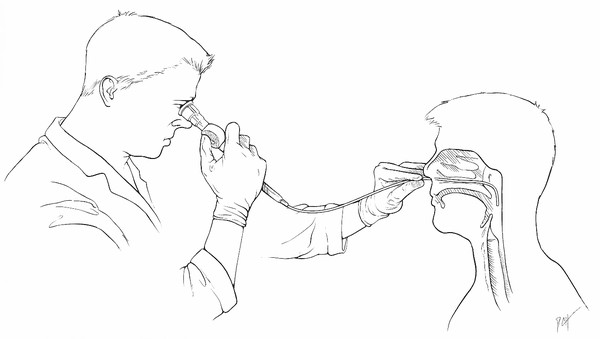

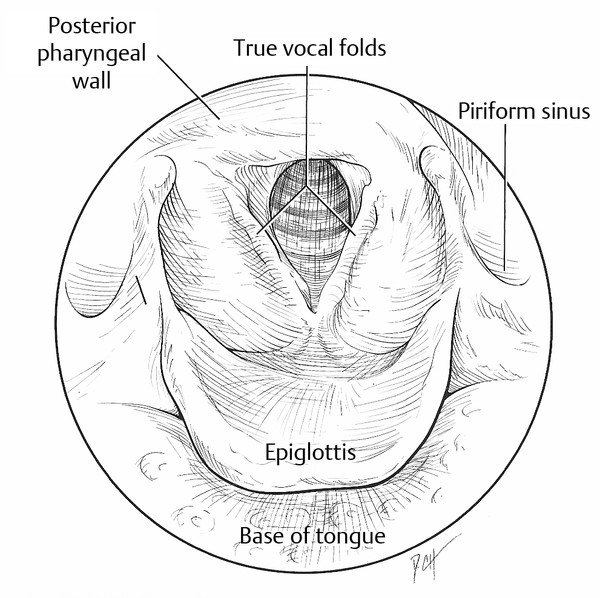

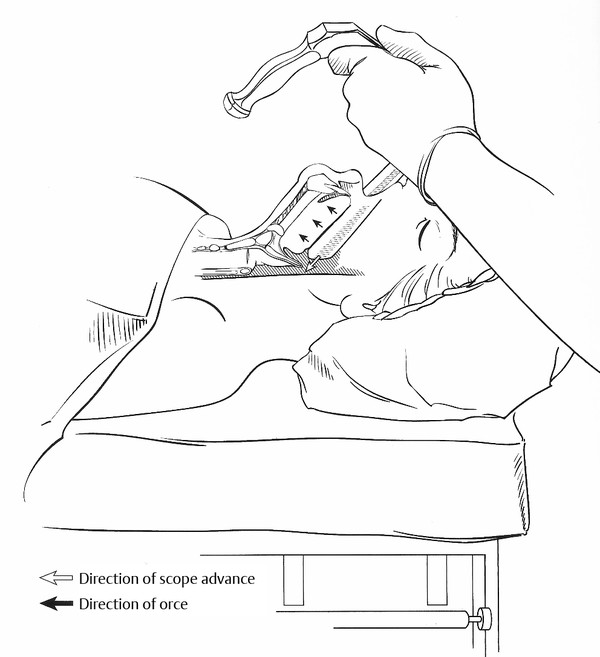

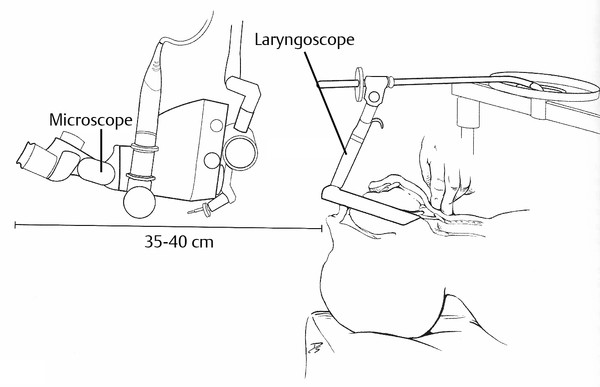

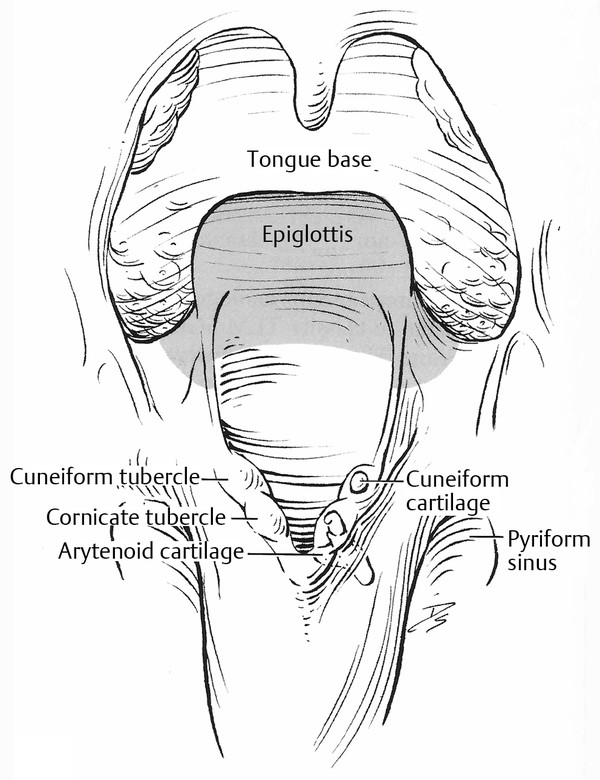

Cancers of the oral cavity are often easily visible, but tumors that arise in the oropharynx, hypopharynx, or larynx are not and often require specialized equipment for adequate examination ( ▶ Fig. 13.1, ▶ Fig. 13.2, ▶ Fig. 13.3). The typical presenting complaints of patients with cancers in these areas include neck mass, ear pain, throat pain, hoarseness, hemoptysis, and difficulty swallowing. Since lesions of these areas are not as easily seen as oral cavity cancers, it is more typical for patients to present with advanced disease. The exception to this is cancers of the glottic larynx, which tend to cause severe hoarseness at an early stage.

Fig. 13.1 Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy. (From Cohen JI, Clayman GL. Atlas of Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 9. Used with permission.)

Fig. 13.2 Endoscopic view of the larynx. (From Cohen JI, Clayman GL. Atlas of Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 9. Used with permission.)

Fig. 13.3 Direct laryngoscopy and pharyngoscopy in the operating room. (From Cohen JI, Clayman GL. Atlas of Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 18. Used with permission.)

13.3 Workup and Staging of Head and Neck Cancer

The term cancer staging describes the extent or spread of the disease at the time of a patient’s diagnosis. Proper staging is essential in determining the choice of therapy and in assessing prognosis, and this determination is based on the primary tumor’s size and whether it has spread to other areas of the body. The TNM staging system classifies how advanced a patient’s disease is by assigning a value to three different variables: the size and extent of the primary tumor (T), whether the cancer also involves the lymph nodes in that area (N), and whether the cancer has metastasized (i.e., spread to another part of the body [M]). Once the T, N, and M values are known, a stage of I, II, III, or IV can be assigned, with stage I representing early, and stage IV representing advanced disease. 1 Generally speaking, higher stages will require more aggressive treatment and have a poorer prognosis for survival. For example, a small stage I tumor of the tongue or vocal fold without nodal involvement (e.g., T1N0M0) might have a successful cure with only one modality (likely surgery or radiation only), but an advanced stage IV cancer of the tongue or larynx (e.g., T3N2M0) would typically require two or more modalities for a good chance of a successful cure.

The diagnosis of SCC of the head and neck requires a biopsy for confirmation. Depending on the location of the tumor and the equipment available, biopsy may be accomplished in the clinic, but certain tumor locations (i.e., the hypopharynx, larynx, and some locations within the oropharynx) may be inaccessible and therefore the biopsy is often performed in the operating room under anesthesia. Biopsy under anesthesia also allows a thorough examination of the remaining portions of the upper aerodigestive tract. This examination serves several purposes, including determining whether the tumor is anatomically suitable for certain surgical procedures and also to rule out the presence of another malignancy in the patient. For HNC, synchronous cancers are discovered about in about 5% of patients. 9

The patient needs a thorough medical evaluation, including preexisting comorbidities, and a physical examination. The details of this evaluation are beyond the scope of this chapter but it needs to include an assessment of the patient’s cardiopulmonary and renal function. The patient’s medical situation may influence the selection of cancer treatment as well as rehabilitative methods. For example, a patient with renal insufficiency may not be a candidate for treatment with chemotherapy and a patient with severe arthritis may not be able to care for and use a tracheoesophageal puncture. Similarly, the patient’s social situation should be investigated. If the patient lives at a distance from the treatment center and lacks the resources for travel, the treatment plan may need to be adjusted. A patient who cannot write will be more severely impacted by loss of voice than one who can write. All of these factors should be considered when selecting the appropriate method of treating and rehabilitating a patient with HNC.

Additional studies may be indicated depending on the particular situation. These may include, but are not limited to, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound examination, and positron emission tomography (PET).

13.4 Oncologic Decision Making

The choice of how to treat the patient’s cancer is predicated on the site and stage of the cancer, the individual medical and social situation of the patient, and his or her own desires. The head and neck oncologist should be able to discuss with the patient the various options available and the pros and cons of each. Multidisciplinary input from the surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, speech-language pathologist, and other medical specialties may be needed, and presentation at a multidisciplinary Tumor Board is encouraged. Treatment decisions should be based not only on which option provides the greatest chance of cure but also on which will result in the fewest functional limitations after treatment. While the morbidity of surgery is obvious to most patients, one should not underestimate the morbidity of the nonoperative modalities of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. It is the experience of the authors that nonoperative management can be just as difficult for the patient as surgical treatment and the patient should be cautioned that nonsurgical options may not be the least morbid option.

Treatment of HNC, as with most other cancers, is based on the triad of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. While surgery and radiation therapy are sometimes used alone, there is little role for the use of chemotherapy alone except for palliation. When chemotherapy is used in treatment designed to be curative, it is always in conjunction with radiation therapy. In general, early-stage disease can be treated adequately with either surgery or radiation therapy as a single modality, with roughly equivalent oncologic results. Therefore, the choice of treatment is often based upon which treatment is less morbid. For example, a small oral cavity cancer can be treated with equal efficacy with either surgery or radiation therapy, but surgery can be accomplished with a single day of treatment as opposed to as many as 7 weeks of daily treatments. In addition, radiation therapy can be expected to cause permanent xerostomia and potentially severe dental problems, so surgery is often preferable. In contrast, a small cancer of the true vocal fold, while easily treated with partial or total laryngectomy, is often treated with radiation therapy, because the vocal results with radiation are clearly superior.

Higher-stage tumors (stage III or IV) typically receive multimodality treatment consisting of combinations of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Tumors of the oral cavity are often treated with surgical resection and postoperative radiation or chemoradiation. Extensive tumors, such as those involving the bone of the mandible or maxilla, may have better survival when treated with surgery than with definitive chemoradiation. 10 However, there is extensive experience with tumors of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx, which show excellent rates of disease control and acceptable morbidity with chemoradiation. As a result, there has been a move toward nonsurgical treatment of advanced tumors in those locations. 11, 12, 13 However, it should not be assumed that merely because the larynx is still present within a patient that it is therefore functional. While randomized studies have demonstrated that patients whose larynx is preserved have superior quality of life in regard to voice and equivalent swallowing quality of life to patients who were not able to achieve laryngeal preservation, there are studies that indicate that findings indicative of locally advanced disease, such as vocal fold fixation and destruction of the cartilaginous framework of the larynx, predict a poor functional outcome after chemoradiation. 14, 15

13.5 Newer Treatment Strategies

While the development of chemoradiation strategies for the treatment of advanced HNC has resulted in decreased use of radical surgery for treatment of these tumors, the recognition of the still substantial morbidity of chemoradiation has been the impetus to develop new strategies that may result in similar oncologic outcomes yet lessen the morbidity of treatment compared to radical surgery and chemoradiation. These options primarily are dependent on recent technological advances that allow transoral access to tumors of the pharynx and larynx. Previously these locations could only be reached surgically with extensive resections through the neck or jaw. Transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) is performed with an assortment of endoscopes and recent series report excellent functional and oncologic results. 16, 17 Another new technique is transoral robotic surgery (TORS), which uses the DaVinci surgical robot to resect tumors of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. Recent series describing functional and oncologic results for patients treated with TORS again report excellent results. 18

These new modalities, while becoming more common, are not suitable for all patients. While the published series describe excellent results, the reports lack the scientific weight of the series of studies that led to the adoption of chemoradiation as a dominant strategy in the treatment of patients with advanced HNC. This is largely a result of the lack of randomized clinical trials comparing the newer strategies and therapy with chemoradiation. The procedures discussed above are being done currently by surgeons with extensive experience in determining which patients are suitable for these treatments, and it is possible that, with wider adoption of the techniques, the results will not be comparable to the early reports. Nonetheless, the development of new technologies and other medical developments share a common goal, namely to provide the best chance of cancer cure with the least negative impact on functional status and the individual’s quality of life.

13.6 The Role of the Speech-Language Pathologist across the Treatment Course

The speech-language pathologist (SLP) may become involved with the HNC patient and his or her family at any point in the continuum of care, from prediagnostic work-up to long-term rehabilitation. The needs of the patient will vary substantially over that time and, consequently, it is essential that the SLP understand the nature and implications of the different phases of treatment and how intervention should best be targeted in order to optimize patient outcomes. In this, the clinician should be guided by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association’s Code of Ethics, which states that clinicians should practice only in those areas in which they have appropriate education, training, and experience. 19 In order to provide optimal care, the SLP must become knowledgeable about (1) the nature of HNC, (2) the different therapeutic modalities for HNC and their impact, (3) the literature regarding optimal rehabilitation methodology and techniques, (4) the nature and use of devices used for management and rehabilitation, (5) the role of various professionals who are involved in the treatment and rehabilitation and how best to coordinate care, and (6) when to refer the patient to a specialist for further work-up or care. In order to be effective, the SLP not only must understand the nature and implications of the treatment itself and how they affect the rehabilitation timeline, but also must be able to tailor the intervention to the specific needs and wishes of the individual, which may also vary substantially from person to person.

In 1972, Virginia Sanchez-Salazar and Anne Stark 20 described a crisis management approach to the recovery process after total laryngectomy. Their model was based on their combined approaches as a social worker and speech pathologist and has been used effectively in the rehabilitation of those who have undergone laryngectomy 21 but it can also be applied to the process that is experienced by many HNC patients in general. The first crisis occurs with the diagnosis of cancer, during which the individual is overwhelmed by catastrophic implications of the diagnosis and fears of the impact of medical treatment, loss of control, and death. The second crisis occurs after recovering from treatment as the full implications of their treatment are felt. If the individual has been hospitalized, discharge is the next crisis, as the patient must leave the protective environment of the hospital, and both the patient and the family may be fearful of whether they can cope. Finally, once the patient has convalesced and friends/family are no longer so attentive, the individual may have to come to terms with the reality of their postoperative status and the fact that they will always be left with some long-term deficits as a result of the cancer treatment. The SLP has a role in all of these phases, and the role varies according to the phase.

13.6.1 Prior to Treatment

The time from diagnosis to treatment is often a whirlwind, both emotionally and practically. Nonetheless, wherever possible, meeting with the patient, family members, caregivers, and anyone who will have a significant role in that individual’s care is of critical importance. Frequently, when an individual is first diagnosed with cancer, they may remember nothing from that initial physician visit other than the diagnosis itself. Furthermore, when the cancer is “treatable” (i.e., is believed to be present locally but not to have metastasized to other parts of the body) there is a medical imperative to treat it before it has a chance to metastasize and, thus, the time from diagnosis to intervention is often extremely short. Consequently, the first meeting with the SLP can be an important time of education, information sharing, and treatment planning for all involved. In this, however, the SLP must be aware of, and sensitive to, the individual’s need for information. Some individuals will want to know all the details of their treatment and its course, while others will want to hear only the most important information in as brief a form as possible and/or to focus only on the most pressing information. Individuals who are about to undergo HNC surgery may retain only a small percentage of what they are told throughout the entire pretreatment period. Thus, information should also be repeated as and when needed and written information should be provided wherever possible for later reference and review, including self-care guidelines and lists of suppliers/resources and support groups. For those who are about to undergo laryngectomy, take-home booklets and materials, such as a copy of Self-Help for the Laryngectomee, 22 are an excellent resource. The specific counseling topics for the preoperative session are listed at the end of this chapter ( ▶ Appendix 13.1), as well as additional resources and readings ( ▶ Appendix 13.2.

Appendix 13.1. Specific Counseling Topics To Be Covered Before Total Laryngectomy

Respiration:

Change in breathing pattern, impact of stoma, need for care and maintenance, including short-term use of mister and suction machines.

Need for “neck breather” Medicalert-style bracelet or necklace.

Swallowing:

Impact on swallowing and need for feeding tube during healing period.

Communication:

Three methods of alaryngeal speech.

Impact of short-term period of voicelessness: planning for communication during hospitalization and at home and ways of getting attention.

Completion and submission of TTY application, if appropriate.

Calling non-emergency number in local phonebook to notify 911 dispatcher of impact of condition (including altered speech/voicelessness and neck-breather status).

General:

Impact of laryngectomy on daily life, including bathing/showering, hygiene, and impact on recreation (e.g., water sports) as well as work-related activities.

Provision of information related to laryngectomy resources, including support groups and the possibility of visitor and written material for review (e.g., Self-Help for the Laryngectomee).

Emergency guidelines and contact information.

Appendix 13.2. Useful Resources and Suggestions for Further Reading in HNC

Further reading for clinicians:

Casper JK, Colton RH. Clinical Manual for Laryngectomy and Head/Neck Cancer Rehabilitation. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group; 1998

Doyle PC, Keith RL. Contemporary Considerations in the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Head and Neck Cancer. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 2005

Graham MS. The Clinician’s Guide to Alaryngeal Speech Therapy. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997

Logemann JA. Evaluation and Treatment of Swallowing Disorders. 2nd ed. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 1998

Reading materials for patients:

Lauder E, Lauder J. Self-Help for the Laryngectomee. San Antonio, TX: Lauder Enterprises; 2011

Keith RL. Looking Forward: A Guidebook for the Laryngectomee. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1995

Keith RL, Thomas JE. The Handbook for the Laryngectomee. 4th ed. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 1996

Support for People with Oral and Head and Neck Cancer. We Have Walked in Your Shoes: A Guide to Living with Oral, Head and Neck Cancer. Locust Valley, NY: Support for People with Oral and Head and Neck Cancer; 2007

Organizations & Websites:

American Cancer Society

250 Williams Street NW, Atlanta, GA 30303

Phone: 1.800.227.2345; Web: www.cancer.org

Head and Neck Cancer Alliance (formerly the Yul Brynner Head and Neck Cancer Foundation)

PO Box 21688, Charleston, SC 29413

Phone: 1.866.792.4622; Web: www.headandneck.org

International Association of Laryngectomees (IAL)

925B Peachtree Street, NE Suite 316, Atlanta, GA 30309

Phone: 1.866.425.3678; Web: www.theial.org

National Cancer Institute (NCI)

6116 Executive Boulevard, Suite 300, Bethesda, MD 20892–8322

Phone: 1.800.422.6237; Web: www.cancer.gov

Support for People with Oral and Head and Neck Cancer (SPOHNC)

PO Box 53, Locust Valley, NY 11560–0053

Phone: 1–800–377–0928; Web: www.spohnc.org

WebWhispers Inc., PO Box 453, Gold Hill, OR 97525

Web: www.webwhispers.org

For the patient and family, pretreatment meeting with the SLP is often beneficial in that it is a time to review important information, to ask questions, and to plan for the future. It is best to begin by asking the patient/family what they have been told previously and what they understand about the nature of the intervention. This will allow the clinician to gain a sense of the level of their understanding, to correct any misperceptions, and to provide new information as needed. Since most individuals have a relatively rudimentary understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the head and neck, colored pictures and diagrams are often helpful in illustrating the location of the cancer itself and how intervention will affect function. The short-term impact of possible interventions should be discussed, including, where appropriate, the presence of a tracheostomy and a feeding tube. The short- and long-term impact of intervention on voice, speech, breathing, and swallowing should be discussed. Planning for short-term and long-term communication should be discussed, whether low-tech (e.g., communication boards, paper and pen) or high-tech (e.g., speech output devices, TTY, electrolarynx, etc.). If a permanent change in communication is anticipated, showing a video of patients communicating by various methods and/or demonstrating the appropriate device may be helpful. If there is to be a permanent tracheostomy, its implications for breathing as well as for functional activities (e.g., showering/bathing, water sports, etc.) should also be discussed. Some individuals may wish to meet or talk with another patient who has gone through a similar type of procedure; if so, appropriate arrangements for a visit should be made. In addition, information about support groups and resources may also be helpful ( ▶ Appendix 13.2). Finally, the timeline for rehabilitation should be reviewed. It is also worth noting that many individuals have a limited knowledge of the nature of the cancer diagnosis and its treatment, and so education should be provided about the rationale for treatment and the importance of follow-up in order to minimize misunderstandings.

Often, family members and other caregivers are looking for guidance about how best to prepare for the individual’s future needs. Information can be shared with them about preparing for discharge home in terms of acquiring skills and knowledge during hospitalization and/or at clinic/training visits, important resources and phone numbers, foods and other items to obtain prior to discharge, and ways of facilitating communication with other friends, family members, or coworkers who may ask for updates. It is often helpful for one family member to function as the “go to” person for phone calls to provide updates to well-wishers and those outside the home. In addition, free medical websites, such as CaringBridge.com, allow for the creation of an individual website that invited members can access and post messages to about the individual’s progress without the need for frequent phone calls.

The pretreatment consultation is a time for the clinician to gather important information, in turn. The SLP will want to assess the individual’s baseline level of function prior to cancer treatment in order to plan more effectively for the rehabilitation course. Factors that may affect treatment decisions and the timing/course of therapy include the extent to which the individual has any of the following: baseline impairments in communication or swallowing due previous treatments for HNC or other neurologic diagnoses; medical comorbidities that may affect recovery; a cognitive impairment; a hearing impairment; reduced capacity for communication via writing; limited social support to assist with postdischarge needs; medical insurance coverage for postoperative rehabilitation; and proximity to a medical center that will enable the individual to attend outpatient therapy, if needed. In addition, factors that are specific to the individual patient will need to be accommodated for therapy to be successful. For example, individuals may have different short- and/or long-term goals depending on their vocational needs, recreational interests, or family responsibilities, which the clinician may be unaware of without more open-ended questioning. The pretreatment consultation is also an opportunity for the clinician to build a relationship and rapport with the individual who is about to undergo treatment and their family.

13.6.2 Short-Term Rehabilitation

The short-term rehabilitative course is often dominated by numerous practical challenges. During hospitalization, those treated surgically may be dealing with immediate postoperative changes, such as pain, fatigue, confusion, the need for assistance with self-care, reduced mobility, reacting to the changed cosmesis as a result of surgery and, possibly, the implications of having a tracheostomy tube and/or a feeding tube. In many cases, the patient will not be cleared for oral intake and must take nothing by mouth (NPO) until cleared by the surgeon. Thus, the early work of rehabilitation may focus on communication using writing, communication boards, and/or text-to-speech devices, if available, as well as on tasks like oral-motor exercises, secretion management, and advancement to decannulation of the tracheostomy, from cuff deflation trials to tolerance of a Passy-Muir valve and/or capping trials. In such cases, close coordination between the surgical coordination between and rehabilitation services is essential for appropriate intervention and optimal outcomes. During this time, the rehabilitation team provides support for the individual and family/caregivers regarding the nature and course of rehabilitation and education about goals for discharge home, if that is appropriate. If not, the patient may need short-term placement at a rehabilitation facility or a skilled nursing facility (SNF) before being independent and medically ready to return home with outpatient follow-up for ongoing rehabilitation needs.This process can be extremely stressful and disruptive for all concerned and, as individuals leave the support and care of the hospital environment, they may doubt their ability to cope and face additional fears about their ability to achieve an acceptable quality of life in the future. Close coordination of team members, including physicians, nurses, rehabilitation staff (PT/OT/SLP), dieticians, and social workers, is critical.

In the patient undergoing chemoradiation, the timeline is substantially different and is covered in more detail later in this chapter. In brief, however, the process may begin with hospitalization for a biopsy, for feeding-tube placement, or, in more extreme cases, for tracheostomy placement due to other acute medical needs. More frequently, however, the patient’s deficits may be relatively mild at the start of treatment but change over the course of treatment as the treatment effects of chemotherapy and radiation cause progressive difficulty, including issues with pain, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, edema, muscle fibrosis, xerostomia (dry mouth), and taste changes. Treatment can cause or exacerbate dysphonia and dysphagia depending on the turmor site. Thus, the treatment course involves teaching compensatory maneuvers and techniques as needed, managing the side effects of treatment, maintaining function by use of exercise to avoid muscle fibrosis and atrophy, and educating the patient/family about the nature of the treatment course. Once treatment is completed and some of the acute side effects have started to subside, more aggressive rehabilitation of residual deficits should begin.

13.6.3 Long-Term Rehabilitation

As the short-term side effects of treatment subside, focus increasingly turns to management of voice speech, and swallowing deficits. The amount of rehabilitation that is required will vary substantially from patient to patient, depending on the severity of the deficits, the patient’s motivation, and the patient’s goals. Most individuals will be seen in an outpatient setting in which the clinician is responsible for designing a treatment program, which will usually entail a home program of exercises to be performed several times daily. While some individuals may require specialized equipment and/or a prosthetic for optimal function, rehabilitation of the HNC patient otherwise uses the same types of techniques and strategies that are employed generally in the rehabilitation of neurogenic speech and swallowing deficits. The rehabilitation of the HNC patient is, however, qualitatively different and there are a few key principles that should guide treatment:

Knowledge about the impact of HNC and its treatment and the particular details of an individual’s treatment course are essential in designing a treatment program.

The focus of therapy may change over time, shifting from compensation/management and maintenance before/during cancer treatment to aggressive rehabilitation once cancer treatment and its side effects subside.

Optimal treatment is usually multidisciplinary, requiring the work of medical and rehabilitative professionals to be coordinated in order to be mutually reinforcing in the accomplishment of common goals.

Communication between providers is essential, as is communication with the patient/family about the impact of HNC treatment, the nature and goals of therapeutic techniques, the rationale for their use, a timeline for rehabilitation, and the need for follow-up with providers.

Therapeutic exercises should be targeted to the areas affected by treatment and should performed aggressively, several times per day, for optimal outcomes. Additionally, therapy exercises designed to strengthen affected musculature should follow the principles of exercise physiology, in that the exercise must be appropriate for the targeted task/behavior (specificity), and tasks must be initiated at a moderately challenging level (intensity) over time (duration), and must then be progressively increased to continue making ongoing gains (progressive resistance).

With regard to dysphagia therapy, in the early stages of treatment, aspiration is often unavoidable. Nutritional support while teaching the individual how to swallow the safest consistencies in limited amounts may be an essential part of the earliest phase of rehabilitation.

These principles are discussed in greater detail in the sections that follow.

13.6.4 The Importance of Care Coordination and Communication

Following the patient’s initial diagnosis, treatment planning begins by presentation of the patient’s case at Tumor Board, a multidisciplinary meeting at which the pathology results and imaging studies are reviewed to determine the appropriate treatment course. At this meeting, a medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, head and neck surgeon, pathologist, and radiologist are usually present, in addition to other specialties that may be involved in coordinating care and treatment, such as a care-coordination nurse or social worker. It has been estimated that more than 20 different medical specialties can be involved with care of the HNC patient and that the coordination of these different services can be “complex and often chaotic.” Because of the number of medical specialties involved in HNC care, communication between health care providers, and between providers and patients, is often inadequate, which can be a source of frustration for all. 24, 25 For this reason, many institutions rely on a care-coordination nurse or social worker to assist the patient and family with issues of scheduling and coordination. There are also numerous educational resources available both online and in written form ( ▶ Appendix 13.2).

13.6.5 Rehabilitation after Head and Neck Cancer Surgery

The three primary modalities for the treatment of HNC are surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. These may be provided either alone or in combination, depending on the type of cancer, its location, and the extent of the cancer’s spread to surrounding tissues, such as adjacent lymph nodes. The goal of any type of cancer treatment is twofold: (1) to eliminate the cancer before it can spread to other surrounding tissues or other parts of the body, wherever possible; and (2) to do so with the least negative impact on the health and quality of life of the individual. In surgical resection, the goal is to remove the tumor itself, leave a healthy margin of tissue that is cancer-free, and then to close or fill the defect in a manner that has the least negative impact on appearance and function, usually speech, swallowing, and/or breathing.

13.6.6 Surgical Intervention

Primary Resection

For small tumors, surgical intervention can take the form of primary resection, in which, after complete removal, there is sufficient viable soft tissue remaining to simply suture the defect closed. For this type of surgery, as with other surgeries in general, the smaller the lesion, the smaller the resection, and thus the less impact the surgery will have on speech and swallowing outcomes. 26, 27 In the case of anterior oral cavity resections, which may involve the lip, anterior two-thirds of the tongue, floor of mouth, or cheek, the patient may experience decreases in sensation, range of motion, and speed of motion. These may result in dysarthria and difficulties with oral management of the bolus during eating. For more posterior resections, which may involve the posterior tongue, tonsil, or soft palate, the patient may experience velopharyngeal incompetence, delayed swallow initiation, and decreased tongue-base range of motion. These may result in difficulties with nasal regurgitation, preswallow spillage of the bolus, aspiration, and hypernasality. Rehabilitation for any type of resection with primary closure may begin as soon as the surgeon clears the patient medically, and this is typically in the acute phase, during the postoperative hospitalization. Intervention may include compensatory maneuvers and strategies, range-of-motion exercises, or aggressive speech and swallow intervention, and it is usually limited only by issues of postoperative pain and swelling.

Minimally Invasive Head and Neck Surgeries

Transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) is a minimally invasive procedure that may be used for HNC ( ▶ Fig. 13.4, ▶ Fig. 13.5). In a transoral approach, the surgeon uses a CO2 laser to target the tumor while limiting damage to uninvolved structures in the surrounding area. This type of surgery can be done on T1–2 tumors of the upper aerodigestive tract. Small oral, tonsillar, laryngeal, and pharyngeal cancers can be removed with TLM.

Fig. 13.4 Patient positioning for transoral laser surgery. (From Cohen JI, Clayman GL. Atlas of Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 392. Used with permission.)

Fig. 13.5 Transoral view of the supraglottic larynx. (From Cohen JI, Clayman GL. Atlas of Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 392. Used with permission.)

Transoral robot-assisted surgery (TORS) may also be used for treatment of oral cavity and oropharyngeal tumors. The surgery is performed transorally with two robotic arms for surgical instruments controlled by the surgeon at a console and one arm for an endoscopic camera ( ▶ Fig. 13.6). This minimally invasive procedure has the advantages of being able to visualize and to access the tumor while minimizing involvement of surrounding structures. This type of surgery can be done on T1–2 tumors, typically without postoperative radiation therapy. Advanced tumors (T1–3, N1–2b) can also be successfully resected, but postoperative radiation therapy is often necessary.

Fig. 13.6 Transoral robotic surgery. (Used with permission from Neil Gross, MD).

Rehabilitation with the minimally invasive transoral surgeries tends to be site specific and can be initiated soon after surgery. Oral feeding is often resumed the day after surgery. As with other surgeries, the nature and extent of the postoperative deficits will depend on the extent of surgery and structures resected. Diet modification is often necessary due to odynophagia, and compensatory maneuvers are also often indicated. Even though the surgery is minimally invasive, patients who have more extensive surgery or who have more deficits at baseline may still require significant prolonged rehabilitation and require a feeding tube during this time.

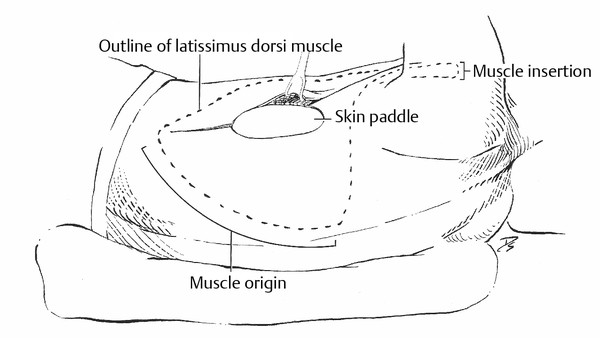

Composite Resection

Often the cancer is not limited to a single anatomical structure, or the tumor size is such that to accomplish regional control, adjacent sites must also be resected, and this is referred to as composite resection. A sizable resection can leave a large defect in the remaining tissue so that there is not enough healthy remaining tissue to close the defect primarily without a significant impact on function or appearance. In these situations, reconstruction is often required using tissue from another area of the body; this may be done with what is called either a local flap or free flap reconstructive procedure. Local flaps involve mobilizing an area of tissue from an area of the body adjacent to the surgical defect and then suturing it into place to close the defect. Some examples of this type of flap include the pectoralis major flap and the latissimus dorsi flap, in which muscle from the chest or back is detached from most of its attachments and moved superiorly to fill in a surgically created defect or to cover an area of exposed tissue. The flap is pedicled, that is it retains a connection to its original blood supply and is not detached completely from its original location ( ▶ Fig. 13.7, ▶ Fig. 13.8). In contrast, free flaps are flaps of muscle, skin, and/or bone, and the veins or arteries that supply them are reconnected to the blood supply in a new area of the head or neck. This is a much more technically complex surgical procedure and requires a reconstructive surgeon to complete the procedure. Examples of this type of flap include radial forearm free tissue transfer, anterolateral thigh flaps, rectus abdominis flaps, fibular free flaps, and jejunal flaps. The latter are often used in pharyngeal reconstruction after total laryngopharyngectomy.

Fig. 13.7 Muscle origin for latissimus dorsi flap. (From Cohen JI, Clayman GL. Atlas of Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011: 580. Used with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree