■ The 360-degree fundoplication (Nissen fundoplication) is the most popular of the various fundoplication techniques.

■ Although fundoplication, when done by an experienced surgeon, results in control of GERD and significant improvement in quality of life in the majority of patients, this operation does fail, necessitating further surgery or a redo fundoplication.1–3

■ Broadly speaking, there are three reasons that an operation will fail to control a patient’s symptoms and/or GERD.

■ Errors in workup or patient selection

■ Errors in operative management

■ Natural history of the particular antireflux operation or condition being treated

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Fundoplication failure is defined as either recurrence of the condition or symptoms that necessitated the fundoplication (e.g., recurrent GERD or recurrent hiatal hernia) or the development of new symptoms not present preoperatively (e.g., dysphagia, nausea, or regurgitation).

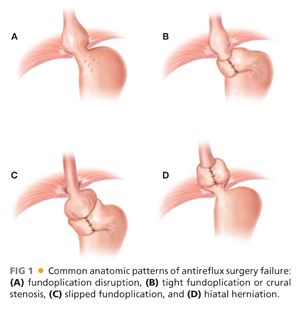

■ One typically sees failure of a fundoplication in a few distinct patterns.4–6 These are outlined in Table 2 and FIGS 1 and 2.

■ When considering these reasons for failure, hiatal hernia is the most common cause (44% of cases). Wrap disruption or breakdown is the next leading cause, accounting for 16% of failures. Slipped wraps account for 11.7% of failure, and finally, wraps improperly positioned at the time of their initial construction is found in 3.9% of cases.7

■ Wrap or crural stenosis is a rare cause of failure and often times hard to determine as a primary etiology of failure.

■ If mesh was used at the initial operation, a distinctly different pattern of failure and management strategy is needed.8

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Common symptoms of failure of fundoplication are outlined in Table 3.

■ Recurrent GERD is the most common (59%) and dysphagia (31%) the next most common. Although these symptoms can occur with any or all of the patterns of failure, there are patterns of symptoms that correlate highly with a given mechanism of failure (FIG 3).

■ Gross anatomic abnormalities such as hiatal hernia or severe wrap/crural stenosis are more likely to present with symptoms related to poor esophageal transit and emptying. These symptoms commonly include dysphagia, chest pain, and regurgitation.

■ The wrap that has loosened or come undone more commonly presents with recurrent GERD symptoms, often identical to those being experienced before the first antireflux procedure. Commonly, this includes typical symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain but can also be more atypical symptoms such as cough, laryngitis, or asthma. Again, the relationship and similarity of symptoms to those before the initial operation is strongly predictive of wrap disruption or loosening.

■ A slipped wrap will often have a broad constellation of symptoms with more prevalence of nausea and epigastric pain than the other presentations.

■ A favorable response to antisecretories and postural regurgitation predicts wrap loosening or incompetence, whereas poor tolerance of heavy dense foods or weight loss predicts hiatal herniation or esophageal outlet issues. Improvement with dilation supports esophageal outlet restriction. Failure of symptoms to respond to any intervention is more likely with wrap slippage.

■ A confusing presentation is the patient with early postprandial bloating or meal-induced diarrhea. With this symptom constellation, one should be suspicious of vagal nerve injury or inflammation (dysfunctional gastric emptying). This symptom complex in the absence of an obvious anatomic abnormality or a positive pH test should lead one to pursue further workup rather than a redo antireflux operation.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Testing for suspected fundoplication failure falls into testing to secure a diagnosis or reason for failure and testing for operative planning. An algorithm for the workup of patients suspected to have failed a prior fundoplication is shown in FIG 4.

Establishing the Diagnosis

■ In pursuit of a diagnosis of failure, the workup should start with an anatomic assessment. This usually includes an upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD]) and contrast esophagram.

■ Often, a contrast esophagram is all that is needed to identify the pattern of failure. FIG 5 depicts the esophagram findings corresponding to the various patterns of failure.

■ Alternatively, an EGD may clearly show an anatomic abnormality. The common endoscopic findings of failure are outlined in Table 4.

■ In many cases, if the presenting symptoms correlate with findings on an esophagram or EGD, this is all that is needed to diagnose failure and the need for reoperation.

■ If recurrent GERD is the dominant presentation, then pH testing should be obtained.

Planning for Operative Management

■ With a diagnosis of fundoplication failure secured, further testing may be indicated to help plan the most effective reoperative strategy.

■ The most common conditions associated with failure that need to be investigated are esophageal motility problems and impairment in gastric emptying. All patients should undergo an esophageal motility study and a gastric emptying study before redo surgery.

■ Impairment in esophageal motility may indicate the need for a partial 270-degree fundoplication rather than a 360-degree fundoplication. Classically, a partial fundoplication should be considered if normal esophageal peristalsis is present in less than 70% of swallows or esophageal body pressure is less than 30 mmHg.

■ Delayed gastric emptying may require the addition of a gastrostomy tube to provide gastric decompression in the early postoperative period, thereby preventing gastric distension–induced crural or wrap disruption.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ Redo fundoplication can be both rewarding and challenging. Although the right diagnosis and proper preparation are important, they are no substitute for experience with all manner of foregut surgery. Redo fundoplication should not be undertaken by a general surgeon who occasionally performs elective fundoplication.

Preoperative Planning

■ For a skilled laparoscopic surgeon, almost all redos can be approached laparoscopically. Early conversion to an open approach is more likely in the following situations:

■ Multiple prior foregut procedures, especially prior open repairs

■ Hiatal hernia with a significant amount of the stomach incarcerated in the chest, especially if mesh was used

■ Prior operations that were complicated by postoperative leak, fistula, or early reoperation

■ In these situations where one may predict a higher likelihood of conversion, it is prudent to be prepared for not only an open approach but also a thoracoabdominal approach.

■ EGD should be available intraoperatively for all redos, and an EGD performed by the surgeon before scrubbing provides valuable firsthand anatomic information that is useful intraoperatively. Leaving the scope in the stomach allows intraoperative identification of key anatomic structures such as the squamocolumnar junction or the location of the fundoplication.

Positioning

■ A split-leg approach is used in nearly all cases (FIG 6). If conversion to an open approach is anticipated, one arm should be tucked so that a table-mounted retraction system can be secured at the patient’s shoulder, well away from the surgeons’ standing position at the patient’s side for open access.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree