Rectal Prolapse: Perineal Approach

Angelita Habr-Gama

Carlos Eduardo Jacob

Rodrigo Oliva Perez

Igor Proscurshim

Treatment of rectal prolapse still represents a significant challenge for colorectal surgeons. Besides being associated with significant patient discomfort, this condition has a remarkable impact on body image, leading to limitation in patients’ normal and social activities. Also, as pathophysiology remains controversial, the preferred treatment strategy is highly variable among surgeons including completely different approaches such as abdominal and perineal accesses for its surgical management.

Perineal rectosigmoidectomy is our preferred treatment option since it not only addresses the prolapse, but also offers the opportunity to deal with concomitant pelvic floor abnormalities frequently associated with this disease, particularly in old patients. Anal encirclement and mucosal sleeve resection may be an alternative reserved for medically unfit patients, for those with very small prolapses, or those with a predominant mucosal component of the prolapse.

Definitions and Cause

Rectal prolapse is defined as an intussusception of the rectum. If the rectal wall has prolapsed but does not protrude through the anus, it is called an occult (internal) rectal prolapse. Most frequently, however, the prolapse is delivered through the anal canal leading to a protrusion of all layers of the rectum (complete rectal prolapse or rectal procidentia) or only of the rectal and anal mucosa (mucosal prolapse).

Initially, this disease was considered a consequence of a pelvic fascia defect, resulting in a sliding hernia. However, several factors were also associated with this disease, such as constipation and difficulty in defecation, pelvic floor atony, patulous anus, and excessive inhibition reflex of pelvic floor. In fact, it is unclear if these physiologic and anatomic findings are causative or consequences of the rectal prolapse. Cineradiologic studies showed that rectal prolapse begins as an intestinal intussusception, a feature frequently used to describe this disease. More recently, anorectal physiology studies identified proximal pudendal nerve injury leading to pelvic muscle weakness as a significant contributing factor to this condition. This pudendal neuropathy appears to be more implicated in associated fecal incontinence than simple mechanical stretching injury to the anal sphincter by the prolapse. Patients with rectal prolapse have abnormal hindgut motility associated with reduced high-amplitude propagated contractions, increased resting colonic pressure, and slow colonic transit.

Irrespective of their possible causative role, several anatomic features are frequently associated with rectal prolapse such as deep Douglas pouch, laxity and atony of the muscles of the pelvic floor, perineal descent, redundancy of the rectum and sigmoid colon, lack of normal fixation of the rectum with an elongated mesorectum, diastases of levator ani muscles, weakness of internal and external anal sphincters,

patulous anus, variable degrees of pudendal neuropathy, and weakness of uterine and bladder ligaments.

patulous anus, variable degrees of pudendal neuropathy, and weakness of uterine and bladder ligaments.

The disease can affect patients of any age. However, there is a bimodal incidence with one peak within the first 3 years and the other after the seventh decade of life. Among young patients, there is an equal distribution between genders. On the other hand, almost 90% of adult patients are female, in the postmenopausal period and often multiparous. Also, history of constipation and previous pelvic surgery are frequent conditions associated with this disease. Curiously, institutionalized patients with psychiatric disorders appear to be at an increased risk for rectal prolapse development, possibly as a consequence of a chronic straining to defecation possibly due to a liberal use of neuroleptic drugs.

The most frequent symptom is the sensation or protrusion of a rectal mass through the anus. Usually, this occurs only during defecation in early stages of the disease. However, such protrusion may ultimately occur during any activity associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure such as coughing (Valsalva maneuver) or even walking. Protrusion is usually reducible and no greater than 15 cm. As the prolapse increases, it often requires manual reduction. Rarely, it may also become incarcerated or even strangulated. Bloody or mucoid discharge can be noticed as it is caused by ulceration and chronic rectal mucosal exposure.

Other associated symptoms include rectal pain and bleeding. Incomplete prolapse should be suspected when the patient complains of tenesmus, rectal pressure, or a sensation of incomplete evacuation.

Straining during defecation and constipation are common complaints among these patients. Possible underlying physiologic mechanisms include intussusception of the rectum, colonic dysmotility, and inadequate puborectalis contraction.

Fecal incontinence is a frequently associated condition affecting around 70% of these patients. This probably results from an interaction of complex mechanisms including inhibition of the anorectal reflex, low anorectal sensitivity, and decreased resting pressure secondary to mechanical dilation of the anal sphincters. In fact, pudendal neuropathy is frequently found in these patients and appears to be the most significant contributing factor to fecal incontinence.

Diagnosis is suspected by history and patients’ complaints. Confirmation is usually straightforward during perineal examination, when the patient is asked to strain. Preferably, patients could be examined while seated on the toilet. The typical finding of a full-thickness prolapse is the presence of circumferential and concentric folds of the rectal mucosa (Figs. 1 and 2). This feature may help in differentiating from the radial mucosal folds commonly present in advanced hemorrhoidal disease (Fig. 3). After reduction of the prolapsed rectum, a careful rectal examination is important to assess anal resting and squeezing pressures. It is imperative to exclude a tumor or polyp as the underlying cause of intussusception, and for this reason colonoscopy is always recommended. In some patients, a solitary rectal ulcer can be seen in the anterior rectal wall due to the trauma of chronic straining.

Patients with rectal prolapse should undergo comprehensive pelvic floor evaluation, before deciding the best surgical approach.

Anorectal manometry usually reveals low resting and squeezing pressures and may provide objective measurement of anal sphincter function before surgery. Electromyography, is useful only to confirm pudendal neuropathy when anal incontinence is associated. Defecography may be elucidative when internal prolapse is suspected as well as in the detection of associated pelvic abnormalities such as rectocele, enterocele, cystocele, and

vaginal, vault, and uterine prolapses. Endoanal ultrasonography may also be useful in the detection of concomitant anatomic sphincter abnormalities or defects that can be addressed during surgical treatment of the prolapse. Colonic transit marker studies should be performed in patients with constipation to exclude colonic inertia or outlet obstruction syndrome.

vaginal, vault, and uterine prolapses. Endoanal ultrasonography may also be useful in the detection of concomitant anatomic sphincter abnormalities or defects that can be addressed during surgical treatment of the prolapse. Colonic transit marker studies should be performed in patients with constipation to exclude colonic inertia or outlet obstruction syndrome.

Over 130 surgical procedures have been described to treat this condition, indicating a lack of consensus as to the ideal surgical approach.

There are two possible surgical approaches to treating rectal prolapse: the perineal and transabdominal approaches. Besides correction of the prolapsed rectum, successful surgical treatment should yield low morbidity and mortality rates; improvement of symptoms, particularly fecal incontinence; and acceptable long-term recurrence rates. Perineal procedures include anal encirclement (Thiersch procedure), mucosal sleeve resection (Delorme procedure), and perineal rectosigmoidectomy (Altemeier procedure). Transabdominal procedures include rectopexy alone or with prosthesis, anterior resection alone or associated to rectopexy, which can be performed through either open or laparoscopic access. The choice of operation should be determined by the patient’s age, comorbidities, operative risk, associated anatomic or physiologic conditions, and history of previous surgery for prolapse.

In general, abdominal procedures are associated with lower recurrence rates ranging from 0% to 11% (mean 5%), and may be a better option for healthy and younger patients. Voiding difficulties and constipation following abdominal suture rectopexy occurs in 27% to 47% of the patients probably as a consequence of some degree of rectal denervation or due to the frequent redundant loop of sigmoid colon left after the procedure.

Since rectal prolapse usually affects the elderly population with numerous comorbidities and high operative risk, the perineal approach may represent an excellent treatment strategy. Perineal procedures allow the use of spinal or locoregional anesthesia and are usually associated with decreased perioperative morbidity rates, shorter hospital stay and recovery to normal activity, less pain, avoidance of peritoneal adhesions, lower risk of injury to the pelvic nerves, when compared with abdominal approaches.

Once the surgeon has decided for a perineal approach and considering anal encirclement as a mere palliative procedure, the choice should be made between mucosal sleeve resection and perineal rectosigmoidectomy. This decision mainly relies on the surgeon’s experience and on the size of the prolapsed rectum. In patients with large prolapses, perineal rectosigmoidectomy may result in decreased recurrence rates as compared with the Delorme procedure. However, in patients with small rectal prolapse, the Altemeier procedure may be technically difficult and inadequate mobilization of the descending colon may lead to ischemia with high risk of anastomotic dehiscence.

Incarcerated and strangulated rectal prolapse are rare conditions that require immediate treatment. If the prolapsed bowel is viable, reduction can be attempted under sedation. If successful, the patient is referred to elective definitive treatment. If incarceration occurs or the bowel is not viable, emergency perineal rectosigmoidectomy is required with or without fecal diversion. Ruptured prolapse and perineal evisceration of small bowel is a critical condition that requires immediate transabdominal repair including closure of peritoneal defect and suture rectopexy.

Preoperative and postoperative care is usually similar for all perineal procedures used for the treatment of rectal prolapse. All patients are admitted the day prior to surgery for mechanical bowel preparation using anterograde solutions. Our preference is for phosphosoda solution, given in two volumes of 45 mL, one at 2 p.m. and the other at 7 p.m. Intramuscular injection of antiemetic medication (bromopride) is usually administered shortly before bowel preparation. More recently, bowel preparation is performed only with liquid diet the day before operation, and a rectal enema before surgery. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy with a second-generation cephalosporin is administered on the day of surgery, shortly before anesthesia with two additional doses. Epidural and general anesthesias are equally effective and are chosen according to patient’s age, general performance status, and associated conditions. Local anesthesia may be sufficient and preferable for anal encirclement due to frequently significant comorbidities. Patients are placed in the modified lithotomy position or in the prone jackknife position followed by urinary catheter insertion.

Anal Encirclement (Thiersch Procedure)

This procedure has the intent to avoid exteriorization of the rectum by encircling and narrowing the anal canal. It was initially proposed by Thiersch using a silver wire, and since then, various other prosthetic materials such as silastic rods and polypropylene meshes have been used.

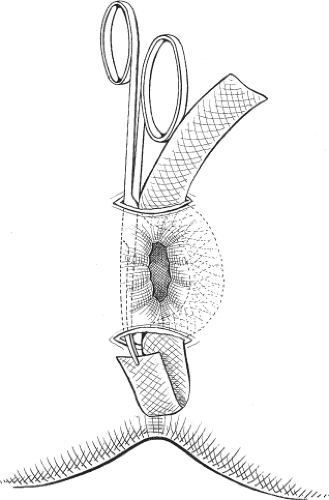

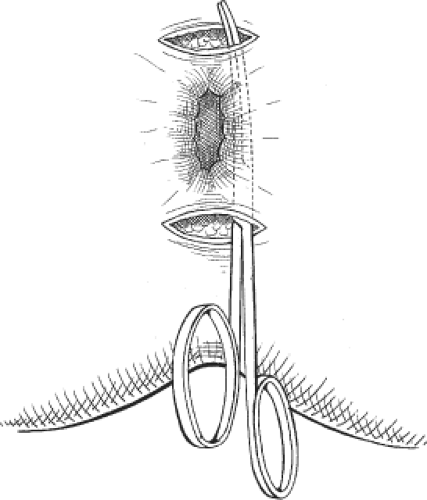

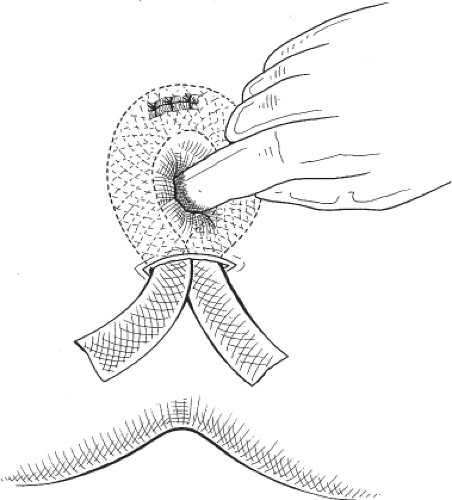

Two small 2-cm incisions are made anteriorly and posteriorly or laterally on both sides of the anus. After creating a submucosal tunnel around the anus using a Kelly clamp, a prosthetic mesh is placed in the subcutaneous layer, leading to partial closure and narrowing of the anal canal (Figs. 4–6). Placement of the mesh in the ischiorectal space may improve results. However, this modification leads to a significant increase in the

extent of the procedure, frequently requiring regional or general anesthesia as opposed to simple local anesthesia.

extent of the procedure, frequently requiring regional or general anesthesia as opposed to simple local anesthesia.

Fig. 4. Two longitudinal incisions are made and a Kelly clamp is used to create a submucosal tunnel around the anus. |

This operation does not eradicate the rectal prolapse but prevents the rectum from descending and exteriorizing through the anal canal. Advantages of this technique are mainly related to its anesthetic and technical simplicity. Disadvantages include high recurrence rates and fecal impaction, occurring in up to 80% of the patients. This technique has fallen into disuse and should be considered only for extremely high-risk patients.

Fig. 6. Calibration of the mesh tension is performed using a finger inserted into the anal canal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|