Theresa Fink and Robert M. Blumm

Reconstructive and Aesthetic Plastic Surgery

Derived from the Greek word plastikos, which means to mold or give form, plastic surgery is a medical specialty that restores or gives shape to the body. There are two different subspecialties of plastic surgery. Cosmetic surgery restores or reshapes normal structures of the body, to modify or improve appearance. Reconstructive surgery treats abnormal structures of the body caused by birth defects, developmental problems, disease, tumors, infection, or injury to restore function and correct disfigurement or scarring. As a surgical specialty plastic surgery owes much of its heritage to knowledge gained from the wars of the twentieth century.

Despite the economic downturn, 14.6 million cosmetic surgical procedures were performed (by surgeons certified by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons [ASPS]) in 2012, a 5% increase in both minimally invasive and surgical procedures. The top five surgical procedures were breast augmentation, nose reshaping, liposuction, eyelid surgery, and facelift. The top five minimally invasive procedures were Botulinum toxin type A injections (e.g., Botox), soft tissue filler injection/insertion, chemical peels, laser hair removal and microdermabrasion. Many cosmetic procedures are performed in outpatient settings (Ambulatory Surgery Considerations). Reconstructive plastic surgery, which improves function and appearance, was up 5%. The top five reconstructive procedures were tumor removal, laceration repair, maxillofacial surgery, scar revision, and hand surgery. Breast reconstruction increased 8% over the previous year with more than 68,000 procedures performed (ASPS, 2012a).

Surgical Anatomy

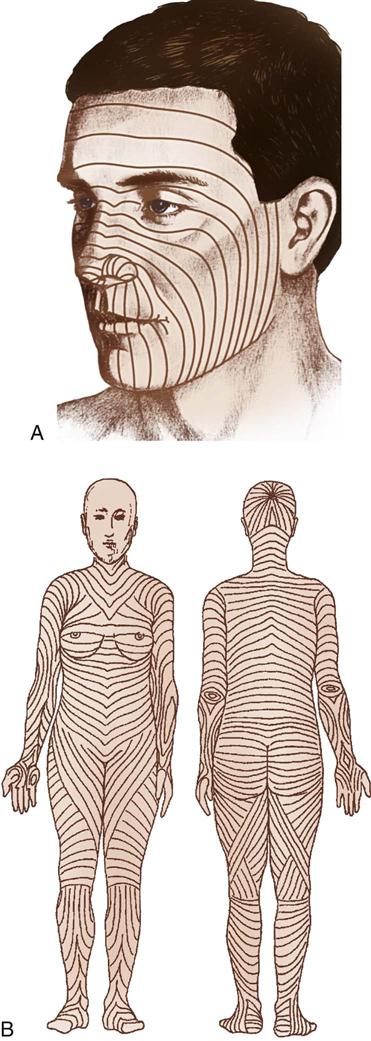

Plastic and reconstructive surgery is not limited to a single anatomic or biologic system. It is based on thorough understanding of the anatomy and biology of tissue. Operative techniques are complex and staged to achieve the expected results. The surgery also involves removing, reducing, enlarging, and recontouring tissue, as well as camouflaging scars into existing skin lines (Figure 22-1). The tissues of the body can be transferred to use as various types of flaps. Free flaps are the transfer of tissue along with its vascular pedicle. When nerve is anastomosed with these flaps, they are called neurovascular free flaps. Flaps are used to cover defects or create new structures such as breasts, digits, or facial structures. Body parts can also be transplanted. By improving the patient’s deformity, the patient’s self-esteem will improve and the patient will feel more comfortable in public and social activities. The body changes as we age. The patient’s concern with aesthetics, the variety of acquired defects, the diversity of operative techniques, and the psychologic responses of patients offer unique learning experiences and challenges for perioperative nursing care.

Perioperative Nursing Considerations

The prospect of surgery, even elective, can produce anxiety and fear. Because it is so often associated with body image and self-esteem, plastic and reconstructive surgery can trigger these emotions, especially when the proposed surgery is associated with potential disfigurement because of disease or trauma. Even a planned (desired) change in body image can be stressful. Many cosmetic patients lack the traditional support system one comes to expect during illness and recuperation because of a desire for confidentiality or because cosmetic surgery is elective and may be viewed by friends or family as nonessential. In these situations the sensitivity of the perioperative nurse is critical.

In general, the nurse creates a therapeutic environment in the following ways: introducing self and other members of the surgical team; explaining all perioperative events and any sensations likely to be experienced; determining the patient’s normal coping patterns; communicating with the patient in a calm, unhurried, and reassuring manner; encouraging the patient to verbalize feelings and concerns, and listening attentively; reducing distracting stimuli in the perioperative environment; providing reassurance and information about the progress of surgery (for awake patients); communicating progress reports to family; providing comfort measures (e.g., warm blankets, soft music of patient preference); and encouraging and assisting the patient to use personally effective coping strategies (e.g., meditation, guided imagery, relaxation) (Patient-Centered Care).

Appropriate candidates for plastic surgery include those who have positive self-image but are bothered by a physical aspect that they would like to improve; after surgery these patients maintain their positive self-image. Another category of appropriate surgical candidates includes patients who have a physical defect or cosmetic flaw that has lowered their self-esteem over time; these patients require time to adjust (rebuild confidence) postoperatively and generally their self-esteem is strengthened, even dramatically. Patients who may not be suitable for plastic surgery include those in crisis or with unrealistic expectations; those who have an unwillingness to learn risks or unwillingness to change the behavior that led to the problem (e.g., a liposuction patient who continues to overeat) and those who are mentally ill/psychotic, delusional, or paranoid (ASPS, 2012b).

The nursing process is dynamic, fluid, and complex. The nature of plastic and reconstructive surgery is rarely simple, routine, or predictable, and the nursing care must mirror that fact. It must include thorough and ongoing assessment, establishment of nursing diagnoses and outcomes, fastidious planning, superior implementation, and thoughtful evaluation. The perioperative nurse’s goal is to produce positive, high-quality outcomes in an environment that is safe and nurturing and will facilitate physical and emotional healing.

Assessment

As part of a holistic assessment, perioperative nurses consider physical and emotional factors of the planned procedure. A comprehensive review of the patient’s chart is the first step. The presence of a signed and witnessed informed consent, a systems review and health history, pertinent laboratory and diagnostic data, interdisciplinary planning, anesthesia evaluation, and the surgical plan disclose vital information necessary to begin the assessment process. Visual assessment should include the patient’s overall physical condition, the condition and integrity of the skin, nutritional status, and physical limitations. The next step is the patient interview, which includes checking patient identification, explaining the perioperative nursing role, and verifying the patient’s understanding of the planned procedure. The perioperative nurse must be skilled in establishing communication quickly to create an instant relationship. Greeting the patient by name in a calm, comforting manner, perhaps with a gentle, caring touch (if welcomed by the patient), and maintaining good eye contact will help establish the rapport needed to assess emotional status, body image disturbances, and anxiety level. Asking the patient questions will help reveal any barriers to communication or learning; religious, cultural, or other preferences; mental status; and insight into compliance. Other vital pieces of knowledge the nurse must obtain include the presence of realistic expectations and motivation for surgery, as well as support systems available to the patient.

An important component of the assessment phase of nursing care involves communication with the surgeon and anesthesia provider to determine the need for special equipment, supplies, sutures, or implants. The perioperative nurse should verify the procedure and position and, in the case of multiple procedures on the same patient, identify the planned order of surgeries.

Clear and effective hand-off communication is critical to patient safety. According to The Joint Commission (TJC), communication is the top contributing factor to medical error and at least 65% of sentinel events. At least half those incidents occurred as responsibility for the patient was transferred from one team of care providers to another. In the perioperative suites, hand-offs occur as patients move to and from the operating room (OR), involving many different care providers for one patient (Association of periOperative Registered Nurses [AORN], 2012). TJC addresses communication in their National Patient Safety Goal 2 (Improve staff communication) (TJC, 2013) and through recommendations around effective hand-offs. The primary objective of a hand-off is to provide information about a patient’s, client’s, or resident’s general care plan, treatment, services, current condition, and any recent or anticipated changes (TJC, 2012). Whatever form the hand-off communication takes at each facility, it must be standardized and provide a thorough discussion of patient history, issues, special needs, and precautions for safety, with opportunity for the receiving provider to ask questions.

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses related to the care of the patient undergoing plastic and reconstructive surgery might include the following:

• Anxiety related to surgical interventions or outcomes

• Risk for Infection related to operative/invasive plastic/reconstructive procedure

• Deficient Knowledge related to perioperative process

• Disturbed Body Image related to congenital or acquired defect or developmental abnormality

• Risk for Ineffective Peripheral Tissue Perfusion related to surgical intervention

• Impaired Comfort related to surgical/invasive procedure

• High Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity and injury related to positioning during surgical procedure

• High Risk for Altered Body Temperature related to procedure

Outcome Identification

Nursing diagnoses lead to the formulation of desired or expected patient outcomes. These are desirable and measurable patient states, including biologic or physiologic states; psychologic, cultural, and spiritual aspects; and the knowledge, behavior, or skills related to these states. As such, the patient outcome indicates progress toward or resolution of the nursing diagnosis. Outcomes should be mutually formulated with the patient, family, and other healthcare providers. Such formulations should be realistic, involve consideration of the patient’s present and potential capabilities and resources, and provide direction for continuity of care, as well as determine satisfaction with that care. Outcomes identified for the selected nursing diagnoses could be stated as follows:

• The patient will verbalize management of anxiety.

• The patient is free from signs and symptoms of infection.

• The patient participates in decision-making affecting the perioperative plan of care.

• The patient will acknowledge feelings about altered structure or function.

• The patient demonstrates knowledge of pain management.

• The patient will be free of injury and have intact skin integrity at the end of the procedure.

Planning

The perioperative nurse designs a plan of care using critical thinking to integrate knowledge gained from prior steps with the plastic surgical patient. The nurse should seek to create and maintain a culture and environment of safety for the patient, the OR, and all members of the surgical team during the planning process. A Sample Plan of Care for a patient undergoing plastic and reconstructive surgery is on pages 826-827.

Implementation

The implementation phase typically begins with preparation of the OR and requires a thorough understanding of the procedure and the special needs of the patient, surgeon, and anesthesia provider. The perioperative nurse must continually monitor and reassess the patient as well as the needs of the perioperative team, implementing and documenting the delivery of care. Constant consideration is given to the safety of the patient and the perioperative environment during this phase.

Preparation of the OR Suite.

Before transporting the patient to the OR, the perioperative nurse will assemble all necessary medical and surgical supplies, equipment, suture material, positioning aids, implantable devices, and medications. The nurse is responsible for ensuring that equipment is in working order, that emergency supplies are present, and that compressed gases are adequate. Depending on the procedure to be performed, the OR bed may need to be configured differently from the standard room setup. To minimize inefficiencies during the procedure the nurse should confirm with the surgeon and anesthesia provider the position of the bed and any proposed intraoperative changes to the bed, room temperature, or room configuration. Plastic and reconstructive surgeons frequently use preoperative photographs of the patient when attempting to restore or modify appearance. These photographs help the surgeon maintain perspective because features may change as a result of surgical positioning. The nurse should collaborate with the surgeon to determine the best placement of these photographs for intraoperative viewing.

Equipment and Special Mechanical Devices.

Essential equipment for any OR includes a fully functional bed that may be positioned for any number of special needs and also has accessory attachments, such as headrests and aids for extremity positioning. The room must also have well-positioned and numerous electrical outlets, good overhead lighting, suction equipment, mounted x-ray view boxes, and computer terminals for those facilities using electronic medical records. Stepstools, tables, chairs, hand tables, tourniquets, microscopes, and intravenous (IV) poles should be in appropriate supply and accessible.

Instrumentation.

Basic instrument trays are available for the plastic surgery OR. A local procedure tray may include Bishop Harmon and Adson tissue forceps (with and without teeth); straight and curved iris, Stevens, and Metzenbaum scissors; fine mosquito forceps; and skin hooks. Minor and major trays for plastic surgery may contain a range of tissue forceps, scissors, hemostats, and retractors. With the addition of instruments for specific surgeries and surgeons, these trays usually suffice for all plastic surgery operations. Adequate instrumentation should be available to avoid immediate use sterilization. Plastic surgeons all have their own instrument preferences that should be discussed and available prior to the procedure.

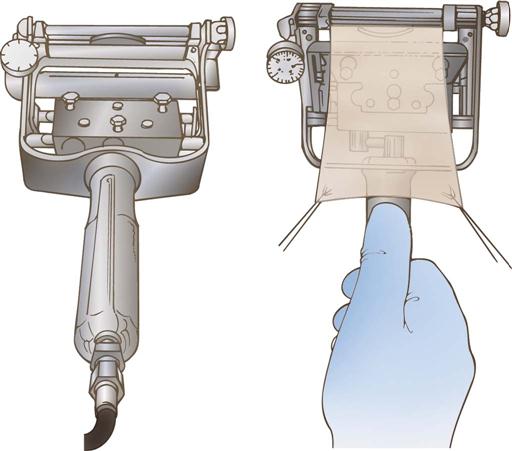

Dermatomes.

Dermatomes are used for removing split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) from donor sites; they are of three basic types: knife, drum, and electric and air driven (Figure 22-2). Sterile mineral oil and a tongue blade should be available when STSGs are being obtained.

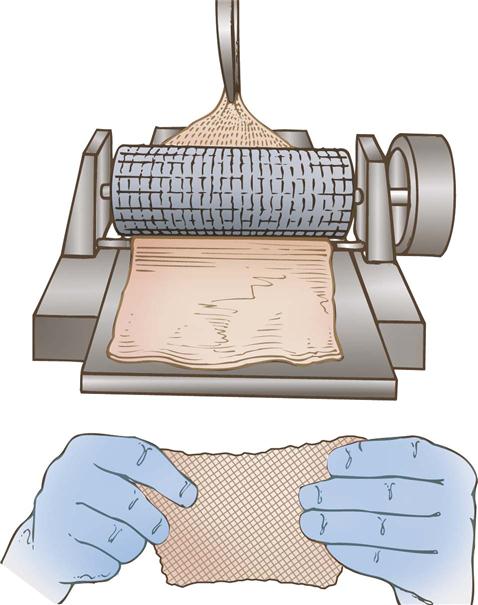

Skin Meshers.

Several types of skin meshers are available, each designed to produce multiple uniform slits in a skin graft, approximately 0.05 inch apart. These multiple apertures in the graft can then expand, permitting the skin graft to stretch and cover a larger area. Meshing also facilitates drainage through the graft, preventing fluid accumulation under a graft. The graft is placed on the carrier and passed through the mesher (Figure 22-3). The manufacturer supplies sterile carriers for meshers. They are usually available in several sizes, which determine the expansion ratio of the skin graft.

Pneumatic-Powered Instruments.

Pneumatic-powered instruments use an inert, nonflammable, and explosion-free compressed gas as their power source. The motor may be activated by a foot pedal or hand control. The various attachments should be sterilized as recommended by the manufacturer to prolong instrument life and ensure effective sterilization. The following attachments may be used in plastic surgery:

A pneumatic tourniquet with an inflatable cuff is used in most hand surgery procedures as well as in other upper and lower extremity surgical interventions. Safe use of the tourniquet is described in Chapter 20.

Hemostatic Devices and Equipment.

Monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical units (ESUs) are commonly used in plastic surgery. The functionality of ESUs and the safety precautions to observe during their use are described in Chapter 8.

Harmonic ultrasonic devices are cutting instruments used during surgical procedures to simultaneously cut and coagulate tissue. They are similar to ESUs but superior in that they can cut thicker tissue, and create less toxic smoke with less thermal damage.

Tissue fusion devices provide a combination of pressure and energy to create vessel fusion. They permanently fuse vessels up to and including 7 mm in diameter and tissue bundles without dissection or isolation an average seal cycle of 2 to 4 seconds. Seals withstand three times normal systolic blood pressure.

Lasers.

A variety of lasers are used for plastic surgical procedures. The perioperative nurse must ensure that the laser safety accessories specific to the type of laser being used are available. Laser safety is discussed in Chapter 8.

Fiberoptic Instruments.

Examples of fiberoptic instrument attachments used in plastic surgery are a headlight for rhinoplasties, augmentation mammoplasties, and other procedures; a mammary retractor for augmentation mammoplasties; a rhytidectomy retractor; abdominoplasty retractors; and endoscopic face and forehead fiberoptic instrumentation.

Loupes.

Loupes (Figure 22-4) are magnifying lenses used by many plastic surgeons for microvascular surgery and nerve repairs and for numerous other instances in which cosmetic results are improved by the magnification effect. The nurse should inquire about the use of loupes before the surgeon dons a headlight because adjustments will need to be made to the headlight alignment if the loupes are required in midprocedure. Adjusting or removing the headlight in midprocedure has the potential to contaminate the sterile field.

Microscope.

The microscope is frequently used in nerve repairs and microsurgical anastomoses; the nerves or vessels to be repaired, such as in hand surgery, and the suture used to do so (sometimes 9-0, 10-0, or even 11-0 size) can be finer than human hair and thus requires magnification. Although each microscope has different features, an important matter to avoid confusion is whether the surgeon control overrides the assistant view, or if each can separately adjust the field of view.

Wood Lamp.

The Wood lamp is an ultraviolet lamp used in a darkened room to determine the viability of skin flaps. After IV injection of fluorescein, the blood vessels appear bright purple (the skin appears yellow). Sodium fluorescein is excreted in the urine, and patients should be informed of this.

Special Supplies.

Surgeon-specific and procedure-specific special supplies are frequently added to instrument setups for plastic and reconstructive procedures. These commonly include the following: sterile marking pen or methylene blue; ruler; local anesthetic of choice for injection, with syringes and needles; and ESU, with active electrode (pencil) and tip of choice, with tip cleaner.

Sutures.

Sutures range from permanent to absorbable and include monofilament and multifilament materials. The perioperative nurse should be a good steward of costly resources and verify the type and number of sutures needed before opening suture packages, as well as needle preference, to prevent waste. Many plastic surgical procedures have multiple techniques, each of which necessitates very specific suture choices. See Chapter 7 for further discussion and explanations.

Dressings.

Dressings are an essential part of the operative procedure in plastic surgery and may contribute to the ultimate outcome of the surgical intervention. Dressings are usually applied while the patient is still anesthetized. In general, the dressing should accomplish the following five goals:

1. Immobilize the surgical part.

2. Apply even pressure over the wound.

4. Provide comfort for the patient.

Pressure dressings may be used to eliminate dead space, to prevent seroma and hematoma formation, and to prevent third spacing associated with liposuction and reconstructive procedures involving transfer of large muscle or tissue flaps. In some cases pressure can be achieved by the use of catheters or drains placed within the operative site and connected to closed-wound suction devices. In smaller wounds a Penrose drain or a butterfly cannula may be inserted into the operative site, with the needle end placed into a red-top tube, such as a blood collection tube, that has a vacuum (evacuated tube).

The perioperative nurse should be familiar with common general dressings and supplies available in sterile form and various sizes.

In some instances, such as a free flap, transparent dressings are used so that the flap can be monitored and observed for vascular flow. Compression garments and support devices are also frequently used by plastic surgeons. Proper fit is essential to minimize vascular compromise. Compression garments are typically applied over a light dressing. A proper garment is selected based on its characteristics (e.g., fabric, stretch, softness, antimicrobial properties) and proper sizing according to measurement instructions. Educating patients of the needs and benefits of compression garment use as well as providing hints for their proper application (avoid ripping with long nails, instructions on how to don the garment) promotes comfort and compliance (Gladfelter, 2007).

Implant Materials.

The range of materials available for implantation and augmentation in the specialty of plastic and reconstructive surgery has benefited from ongoing research and includes prosthetic and natural materials. Perioperative nurses are responsible for complying with tracking regulations for implantable materials and devices (Patient Safety).

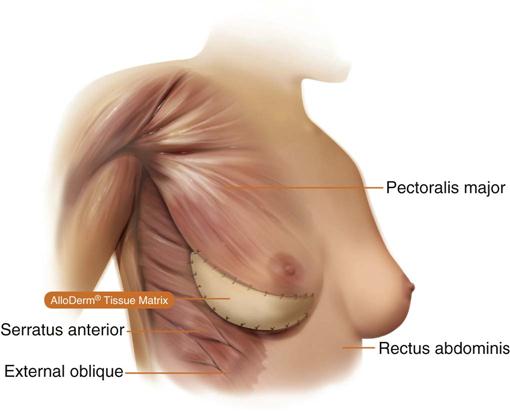

Biologic materials (autogenous grafts) are preferred when available. Autologous human tissue successfully used includes fat, solid dermis, and collagen. A cellular collagen (AlloDerm regenerative tissue matrix) is a material that allows for a strong intact repair in breast reconstruction post-mastectomy procedures by providing soft tissue reinforcement or replacement. Human cadavers are used as a source for AlloDerm (Figure 22-5). This product is available in various sizes of sheeting and must be rehydrated in several steps. AlloDerm integrates with the body’s tissue and helps prevent rejection over the long term, which allows for a safe and clinically optimal outcome (Life Cell Corporation, 2012).

Implant failure may be directly linked to bacterial contamination; therefore meticulous aseptic technique with minimal handling is essential when using implants of any sort. Most alloplastic implants are presterilized from the manufacturer.

Anesthesia.

A variety of anesthetic techniques are used with plastic surgery procedures. Local, regional, tumescent, conscious sedation, deep sedation, and general anesthesia may be used, depending on the type of procedure, the patient’s anesthetic history, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, and the surgeon’s preference. Regardless of the type of anesthesia, patients should have baseline vital signs recorded and fully monitored, including blood pressure, heart rate, respirations, cardiac rate and rhythm, oxygen saturation, and end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) pressure if indicated. When using oxygen on a head and neck procedure, oxygen must be temporarily shut off while the ESU is being used due to its flammability. If a local or regional anesthetic is used without an anesthesia provider, appropriate staffing should be determined based on patient assessment and nurse competency. The presence of a perioperative registered nurse whose sole responsibility is to monitor the patient may be warranted, depending on clinical assessment and patient behavior. This nurse must be sufficiently skilled in assessment and knowledgeable about the agents being used so that changes in the patient’s status can be promptly reported and appropriate interventions to prevent complications can be initiated (AORN, 2013a).

Injectable anesthetics are frequently used, not only for strictly local cases but also in conjunction with regional, sedation, and even general anesthesia. Local anesthetics (e.g., lidocaine, bupivicaine, prilocaine) act by reversibly blocking nerve impulses—they stop nerve conduction by blocking sodium channels in the axon membrane. When combined with a vasoconstrictor such as epinephrine, local blood flow is decreased and systemic absorption of the anesthetic delayed. This prolongs anesthesia time and reduces the risk of toxicity. Sodium bicarbonate also can be combined with local anesthetics to decrease pain during injection by changing the pH of the solution. In addition, infiltration of a local anesthetic can help define tissue planes through hydrodissection. Use of epinephrine is contraindicated in areas with limited vascularity, such as digits, the penis, nasal tip, and ears. Additional information about the use of local anesthetics is found in Chapter 5.

Topical anesthetics used by the plastic surgeon include tetracaine (Pontocaine) 2% ophthalmic drops (for blepharoplasty or before application of eye shields), EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics) for penetration on intact skin (associated with laser surgery), and cocaine solution applied on neurosurgical patties for mucous membranes (for rhinoplasty).

Preoperative Skin Preparation.

Most surgical interventions require that the operative site and adjacent areas be cleansed with an antibacterial soap before surgery. The surgeon may prescribe that the patient carry out this treatment before surgery. Special attention is given to the fingernails for patients undergoing hand surgery; to hair for surgery of the head, face, or neck; and to oral hygiene for surgery in or near the mouth. The perioperative nurse should verify with the patient that the prescribed regimens have been performed. All body jewelry that pierces the skin should be removed before the skin prep. The operative site should be inspected for any rashes, bruises, open sores, cuts, or other skin conditions. Hair should only be removed if it interferes with the procedure. Shaving is avoided and clippers, not a razor, are used if needed, because shaving creates an access for the entry of bacteria into the operative site (AORN, 2013b). The eyebrows and eyelashes, in particular, are left intact to preserve facial appearance and expression. The surgical site is marked before surgery by the surgeon to designate the correct site and to define landmark areas. Either a povidone-iodine solution, an iodine-alcohol mixture, chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG), or another broad-spectrum agent may be selected for the antimicrobial skin prep. The use of CHG should be avoided around the ears and eyes. It is important to place shields on the eyes and/or eye ointment if prepping the periorbital site or performing an extensive head and neck prep, and to place plugs in the ear canals, and prevent pooling of the prep agent. The perioperative nurse should query the patient regarding any allergies to antimicrobial agents. If indicated, the plan of care should be changed to avoid the use of these products. When prepping for a skin graft procedure, separate skin prep setups are needed for the graft and donor sites.

Positioning and Draping.

The OR bed must be positioned so that the remaining space in the room can comfortably accommodate anesthetic equipment, members of the surgical team, instrument tables, and any adjunct equipment (hand table, drills, microscope, laser) to be used. The patient is carefully positioned on the OR bed so that all operative sites may be appropriately exposed and the airway easily observed and accessed.

Before implementing any positioning changes, the perioperative nurse should verify the appropriate placement of the OR bed and the desired patient position. Adequate numbers of personnel and supportive positioning devices must be present. No changes should begin until the anesthesia provider gives permission. Whereas a majority of plastic surgical procedures are performed in the supine position, many also take place with the patient prone or lateral. Liposuction and post-bariatric body contouring procedures may also require repositioning one or more times during surgery. Abdominal procedures may start supine and usually require repositioning to facilitate closure. With each new position, reassessment and documentation of the position and devices used to stabilize the patient should occur. Chapter 6 reviews patient positioning and appropriate safety measures for the supine, lateral, and prone positions, all of which may be used during plastic surgical patient care. The perioperative nurse pays particular attention to the patient’s arms during positioning to ensure that they are placed on padded armboards with the palms up and fingers extended (for the supine position). Armboards are maintained at less than a 90-degree angle to prevent brachial plexus stretch. If there are surgical reasons to tuck the arms at the side, the elbows are padded to protect the ulnar nerve, the palms face inward, and the wrist is maintained in a neutral position (Denholm, 2009). A drape secures the arms. It should be tucked snuggly under the patient, not under the mattress. This prevents the arm from shifting downward intraoperatively and resting against the OR bed rail.

Correct draping procedures depend on the location of the operative site or sites. Disposable drapes (see Chapter 4) are often used because of their barrier qualities, ease of handling and storage, and versatility in adapting to a variety of plastic surgery procedures. Three frequently used draping techniques in plastic surgery are the head drape, chest drape, and hand drape. These draping techniques have the goal of providing maximum mobility of the operative part. The head drape includes a fluid-resistant drape that encircles the head and the addition of a drape to cover the remainder of the body. The following techniques represent methods of obtaining maximum accessibility and sterile coverage for facial surgery:

Additional Considerations.

Preparation is a key ingredient in success. Having backup supplies or equipment, sometimes as elementary as an extra bulb for the light source, can mean the difference in a positive outcome for the patient. Occasionally during the course of a procedure, a flap may become congested and fail, the anatomy may dictate a change in the surgical plan, or perhaps a preselected implant just may not be right. Flexibility, meticulous preparation, and a willingness to improvise and innovate will always serve the perioperative nurse well when working with plastic surgeons.

Evaluation

During the surgical intervention the perioperative nurse is constantly evaluating the patient’s response to nursing interventions, anesthesia, and the surgery itself. Progress or lack of progress toward the identified patient outcomes is continually assessed. The results of this ongoing evaluation enable the perioperative nurse to reassess the patient, reorder priorities of patient care, establish new patient outcomes, and revise the perioperative plan of care.

At the conclusion of the surgical intervention the perioperative nurse reviews whether identified patient outcomes have been achieved. The patient’s skin integrity is assessed; dressings are applied and their integrity is established before discharge from the OR. Any drains or tubes incorporated in the dressing should be noted. Infusion sites are inspected, and the type of infusing solution, flow rate, and amount infused are noted in the patient record. Local anesthetics, sedatives, or other medications received by the patient are similarly documented. The patient’s response during the perioperative period is noted; any unusual or untoward responses are reported to the nurse in the recovery unit. The transport vehicle is obtained; any special equipment needed for patient transport is also obtained and checked for proper functioning. Warm blankets may be provided, and the patient is gently moved to the transport vehicle. The patient who is recovering from general anesthesia is placed in a safe position on the vehicle; the awake patient should be assisted to a position of comfort.

The perioperative nurse, in collaboration with the anesthesia provider, should give the hand-off report to the nurse in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Areas requiring ongoing patient observation should be noted in this report; the patient’s preoperative, intraoperative, and immediate postoperative statuses are also reported. Using the Sample Plan of Care introduced earlier in this chapter, the perioperative nurse may give part of the report based on patient outcomes. If they were achieved, they may be stated as listed under the Outcomes section.

Patient and Family Education and Discharge Planning

Education of the plastic surgery patient begins at the time of consultation. Anxiety inhibits the retention of information; therefore, it is always helpful to have written information or other tools for the patient to use as a reference source, beginning with the preoperative instructions as well as postoperative information. The approach to teaching should lend itself to the patient’s preferred learning style (e.g., auditory, visual). Specifics that should be addressed include pain management, self-care, diet, exercise, care of incisions and drains, return to the clinic for follow-up appointments, signs and symptoms of infections or complications, and how to reach the surgeon in case of an emergency.

Benefits of an effective education intervention are numerous; it serves to decrease anxiety, improves compliance, reduces the incidence of complications, empowers the patient to become an active participant in his or her own care, and maximizes independence, allowing the patient to more quickly return to an optimal state of health. The patient’s readiness to learn, needs, and styles of learning must be assessed. A teaching plan should be individualized based on the desired outcomes of all parties. The teaching should be implemented with respect to the most effective methods of learning for the individual, taking into account cultural, psychologic, physical, and cognitive limitations.

Surgical Interventions

Reconstructive Plastic Surgery

Reconstructive plastic surgery seeks to restore or improve function after trauma, disease, infection, congenital anomalies, or acquired defects while trying to approximate an aesthetic appearance.

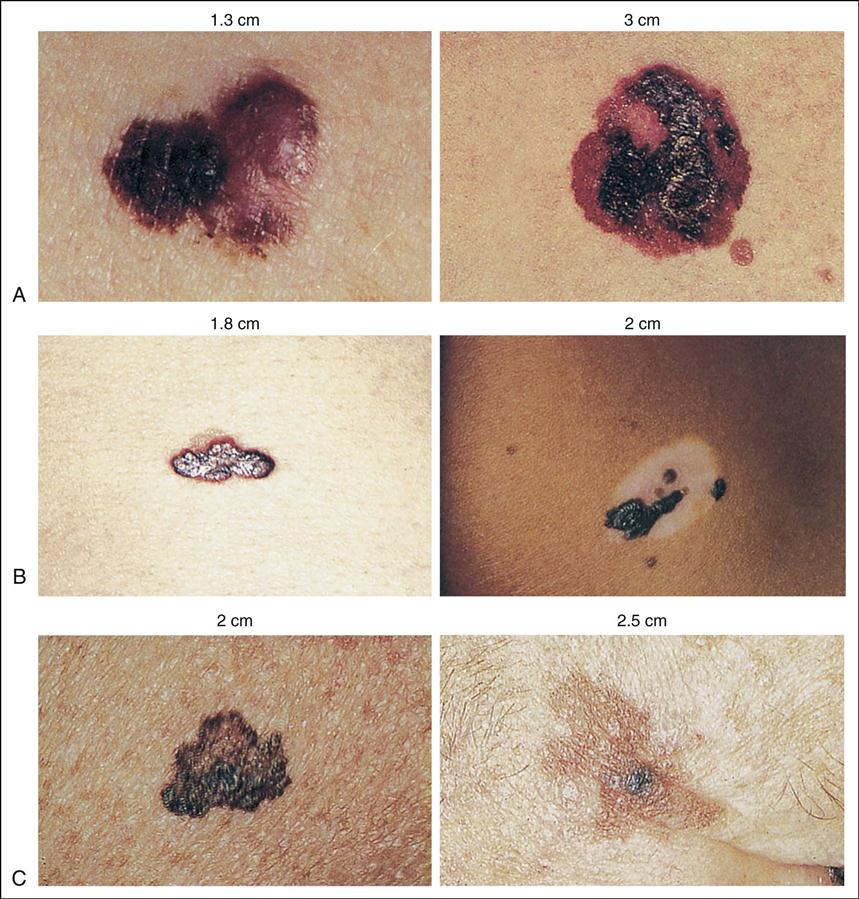

Removal of Skin Cancers

The estimated number of new skin cancer cases diagnosed in 2012 was 2 million (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2012). The three most common skin cancers are basal cell, squamous cell, and melanoma (McCance, 2012). Basal cell cancer accounts for approximately 70% of all skin cancers (Figure 22-6, A). If basal cell cancer is left untreated, it will grow locally, but rarely metastasizes (Box 22-1). Treated early, it may be cured by simple excision and closure (with pathologic diagnosis to ensure disease-free margins). The second most common form of cancer is squamous cell carcinoma. Squamous cell skin cancers are considered more aggressive (see Figure 22-6, B). Surgical treatment is the same as that for basal cell carcinomas. Melanoma accounts for the smallest percentage of skin cancers but it is treated much more aggressively because of its high mortality rate, with an estimated 9480 deaths to occur in 2013 (NCI, 2013) (see Figure 22-6, C). Excision of melanoma may involve sentinel node mapping and excision. Early diagnosis of melanoma is imperative to successful treatment (Evidence for Practice).

Procedural Considerations.

Consideration must be given to the type of skin cancer to be excised and the anticipated closure technique. Simple excision and closure with adjacent tissue is the simplest technique, requiring a local plastic tray accompanied by skin markers and an ESU, and usually involving use of a local anesthetic with epinephrine. A simple excision may be performed with the patient administered a local or general anesthetic or after induction of sedation. If additional procedures will be performed (e.g., reconstruction with skin graft, flap, or sentinel node mapping), refer to those sections for additional procedural considerations.

Operative Procedure—Simple Excision

Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery is a specialized excision used to treat basal and squamous cell skin cancers. The procedure involves excising the lesion layer by layer and examining each layer under the microscope until all the abnormal tissue is removed.

Procedural Considerations.

Mohs surgery is usually completed on an ambulatory basis with the patient administered a local anesthetic. The procedure can be very time-consuming to accomplish, but it typically results in the preservation of the surrounding healthy tissue. Because the procedure is lengthy, patient preparation and comfort are essential to facilitate cooperation during the procedure. A minor plastic surgery set is required, along with fine (5-0 or 6-0) suture material.

Operative Procedure.

Current procedures involve removal of all visible portions of the skin cancer lesion. A horizontal layer of tissue is removed and divided into sections that are color-coded with dyes. A map of the surgical site is then drawn. Frozen sections are immediately prepared and examined microscopically for any remaining tumor. If tumor is found, the location or locations are noted on the map and another layer of tissue is resected. The procedure is repeated as many times as necessary to completely remove the tumor. The patient may be referred to a plastic surgeon for reconstruction of the defect after completion of the Mohs procedure.

Burn Surgery

A majority of burns result from exposure to high temperatures, which injures the skin. Flame, scalding, or direct contact with a hot object may cause thermal skin injury. Similar destruction of skin can result from contact with chemicals such as acid or alkali or contact with an electrical current. The latter, however, often involves extensive destruction of the underlying tissue and physiologic systems in addition to the skin. Approximately 450,000 burn injuries receive medical treatment yearly; 40,000 patients are hospitalized in the United States for burn injuries, with 30,000 of those admitted to the 127 hospitals with specialized burn centers (American Burn Association [ABA], 2012).

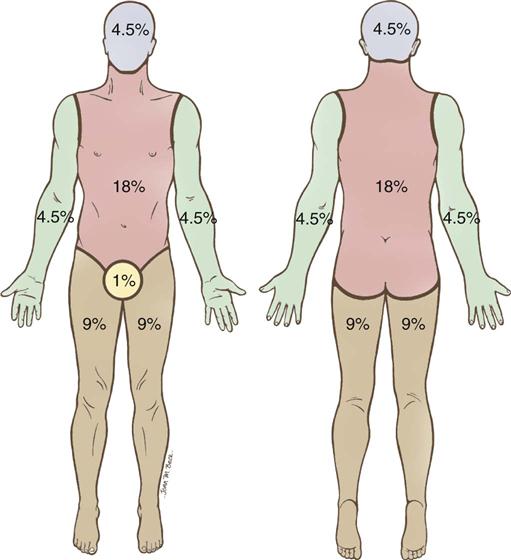

Intact skin provides protection against the environment for all underlying tissues and organs. It aids in heat regulation, prevents water loss, and is the major barrier against bacterial invasion. The tissue injury resulting from a burn disrupts this normal protective function, resulting in local and systemic effects (Box 22-2). Burn patients are therefore some of the most acutely ill patients brought to the OR. The greater the degree of injury to the skin, expressed in percentage of total body surface area (BSA) and depth of burn, the more severe the injury. One method of measuring BSA in adults is by use of the “rule of nines” (Coffee, 2013) (Figure 22-7).

Partial-thickness (first- and second-degree) burns heal by regeneration of skin from dermal elements that remain intact. First-degree burns involve the epidermis, which appears pink or red; sunburn is usually a first-degree burn. Second-degree burns, also called partial-thickness burns, involve the epidermis and some of the dermis. Full-thickness (third-degree) burns (Figure 22-8) involve the epidermis, the entire dermis, and the subcutaneous tissues; they require skin grafting to heal because no dermal elements remain intact. Both partial- and full-thickness burns may require debridement of necrotic tissue (eschar) before healing can occur by skin regeneration or grafting. An allograft may be used to cover the burned area during the initial healing process. However, the allograft must be carefully tested for immunodeficiency diseases. A xenograft (e.g., pig skin) may also be used for covering the burned area.

Procedural Considerations.

The essentials of skin grafting are discussed later in this chapter. This section therefore deals only with the procedure for debridement of burn wounds.

A basic plastic instrument set is required, plus a knife dermatome, an ESU, topical thrombin solution, a pneumatic tourniquet for isolated extremity burns, and a topical antimicrobial agent of choice.

Because patients who have sustained burns are vulnerable to hypothermia from the loss of BSA, the perioperative nurse should ensure the temperature and humidity in the OR are increased and exposure is limited only to the areas related to the planned surgical event. Anesthesia is often induced while the patient is on the burn unit bed; transfer to the OR bed is done carefully and gently, with attention to maintaining the airway. Most burn patients arrive in the OR with dressings covering their wounds. The dressings are removed after the patient has been anesthetized to minimize pain and loss of body heat through the open burn wounds. Throughout the procedure, the temperature in the OR is constantly monitored to prevent hypothermia. The OR team caring for burn patients coordinates activities to prevent any delays in obtaining required equipment or supplies. The perioperative nurse will need to collaborate with the anesthesia provider in determining fluid replacement requirements. A variety of topical agents are used to dress wounds. Perioperative nurses must be familiar with these agents and their uses (Surgical Pharmacology).

Surgical Pharmacology

Topical Medications Used in Burn Therapy

| Medication and Category | Dosage and Route | Purpose and Action | Adverse Reactions | Nursing Implications |

| Petroleum-based antimicrobials (bacitracin, polymyxin B, Neosporin) | Topical (500 units/g): Apply 1 to 5 times a day as directed | Partial-thickness burns Provides barrier protection to wound Has broad-spectrum antimicrobial action against gram negative, gram-positive, and candida organisms Minor skin abrasions, superficial infections, prophylactic postsurgical wounds | Rash, burning, inflammation, pruritus | Gently cleanse wound prior to application; evaluate for hypersensitivity reaction. |

| Silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) | Topical: Apply 1 or 2 times a day as directed | Deep partial to full-thickness burns Wound infection | Burning, stinging at treatment site; fungal superinfections may occur; toxic nephrosis possible with significant systemic absorption | Apply to cleansed, debrided burns using sterile gloves; keep burns covered with silver sulfadiazine at all times. |

| Mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon) | Topical cream (1 g): 2 or 3 times daily 11.1% cream: Penetrates thick eschar and cartilage 5% solution: Antimicrobial solution used to treat and prevent wound infections | Deep partial to full-thickness burns Wound infection Is bacteriostatic against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria Diffuses through devascularized areas, is absorbed, and rapidly converts to a metabolite | Pain on application, metabolic acidosis, hypersensitivity rash, fungal growth | Discontinue when eschar no longer present; may need pain management during application. |

| Silver nitrate (5% solution) | Topical: Apply 2 or 3 times per week for 3 weeks | Deep partial to full-thickness burns Wound infection Has poor penetration of eschar Is bacteriostatic against gram-negative and gram-positive organisms | Skin discoloration, pain on application, staining of clothes and linens, decreases in electrolytes | Apply with cotton-tipped applicator; treat only affected areas. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree