Radical Groin Dissection

Daniel G. Coit

Groin dissection is a procedure performed in the treatment of a number of cutaneous malignancies, including melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and other skin appendage tumors metastatic to that nodal basin. Other primary tumor sites potentially metastatic to the superficial groin include the vulva, anus, and penis. Visceral sites potentially metastatic to pelvic nodes include cervix, endometrium, prostate, and bladder. This chapter deals specifically with lymphadenectomy for metastatic disease to regional nodes, and does not specifically address resection of benign or malignant soft-tissue neoplasms of the groin region. Furthermore, it focuses on the technical details of open surgical lymphadenectomy, rather than the minimally invasive laparoscopic approach.

Through the 1980s, perhaps the most common indication for groin dissection was in the elective setting for intermediate thickness melanomas of the trunk or lower extremities. However, the overall incidence of groin dissection for melanoma has decreased dramatically over the last 20 years. In the absence of prospective data to support routine application of elective lymph node dissection, and with the advent and subsequent widespread application of sentinel lymph node biopsy, the principal indications for this procedure in melanoma have evolved toward either selective or completion lymph node dissection in patients with positive sentinel nodes, or therapeutic lymph node dissection in those with clinically positive regional nodes, both in the absence of known distant metastatic disease. The procedure may be unilateral, or, in the case of midline primary tumors, bilateral. The procedure may entail removal of inguinofemoral nodes in the superficial groin, that is, those nodes superficial to the inguinal ligament, the ileo-obturator nodes deep to the inguinal ligament in the pelvis, or both.

Although never formally confirmed in the context of a prospective randomized trial, in the absence of distant disease, few would argue with the therapeutic value of complete lymph node dissection in patients with clinically positive nodes. A substantial proportion of these patients are cured with no further treatment beyond complete surgical resection. On the other hand, the therapeutic value of completion lymph node dissection in patients with a positive sentinel lymph node from melanoma is unknown, and is currently the focus of an ongoing prospective randomized study, the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II.

In patients with known distant metastatic disease, palliative groin dissection may be indicated to achieve control of symptomatic regional disease in the nodal basin. Given the substantial morbidity of the procedure, groin dissection to control potential future symptoms in the presence of known systemic metastases should be done sparingly if at all, and if so, only on a case-by-case basis.

The anatomy of the groin is quite constant. The superficial groin is defined by the femoral triangle, consisting of the sartorius muscle laterally, the adductor magnus and pectineus muscles medially, and the inguinal ligament superiorly. The transition from external iliac to common femoral vessels occurs as they traverse the femoral canal from the pelvis into the thigh. Medially in the femoral canal, there are lymphatics containing Cloquet’s lymph node. Proceeding laterally, we encounter the common femoral vein, the common femoral artery, and more laterally, the common femoral nerve. The saphenous vein enters the inferior apex of the femoral triangle at the junction of the adductor magnus and sartorius muscles, and courses through the middle of the triangle, through the fossa ovalis, to drain into the common femoral vein at the saphenofemoral junction. Branches of the saphenofemoral junction include the lateral femoral circumflex, medial femoral circumflex, external pudendal, superficial circumflex iliac, deep circumflex iliac, and superficial epigastric veins. The exact anatomy and caliber of these veins varies from one patient to the next; most of these veins have corresponding arteries. As all of these small vessels traverse the lymphadenectomy

specimen, each requires division at both the periphery and the center of the lympha-denectomy.

specimen, each requires division at both the periphery and the center of the lympha-denectomy.

Working cephalad, just above and deep to the inguinal ligament, the common femoral vessels become the external iliac vessels. Immediately deep to the inguinal ligament, the deep circumflex iliac artery and vein course laterally, while the inferior epigastric artery and vein arise medially to course along the undersurface of the rectus abdominus muscle. Proximal to these two vessels, there are no further named branches of the external iliac vessels. Working cephalad further, we encounter the bifurcation of the common iliac into the internal and external iliac vessels. The internal iliac vessels branch widely. The first branch is the superior gluteal, which traverses the sciatic notch to the buttock, and represents an important source of collateral circulation to the lower leg in the event of external iliac interruption. Other branches include the inferior and superior vesical, the internal pudendal, the obturator, and the superior and middle hemorrhoidal vessels. Not all of these branches can be traced out in every pelvic lymphadenectomy. Traversing the triangle between the external and internal iliac vessels is the obturator nerve, which joins the obturator artery and vein to exit the obturator foramen. Medial to the deep pelvic node compartment is the peritoneum and its contents, and the retroperitoneal structures of the ureter, rectum, and bladder. The lateral aspect is bordered by the endopelvic fascia.

Anesthesia

Groin dissection is most commonly performed under either regional or general anesthesia. If pelvic lymphadenectomy is to be undertaken, muscle relaxation is important to achieve adequate exposure, and general endotracheal anesthesia is preferred. Bladder catheterization is generally not necessary unless a prolonged and difficult procedure is anticipated.

Positioning

The patient is generally positioned supine on the operating room table, with the ipsilateral hip slightly abducted and the knee flexed. This opens up the femoral triangle. The knee can be rested on a pillow for support. The surgical field may be prepped and directly squared off, or the entire lower extremity may be prepped and draped into the field, at the discretion of the operating surgeon. We employ compression boots on one or both legs, depending on whether or not the ipsilateral leg has been prepped into the field.

Incision

There is a variety of incisions, which can be used to performed groin dissection. Many of the short-term wound-related complications associated with the superficial groin dissection are a consequence of a vertically oriented incision, which traverses the groin crease. This incision is subject to a great deal of motion and stress, and often fails to heal primarily. Modifications of the vertical incision include the oblique incision oriented along lines of skin tension, either above or below the groin crease. One recent prospective randomized clinical trial suggested that a suprainguinal skin crease incision was superior to an infrainguinal skin crease incision, as measured by improved cosmesis and less pain, with insignificant trends toward fewer wound dehiscences and fewer lymphoceles.

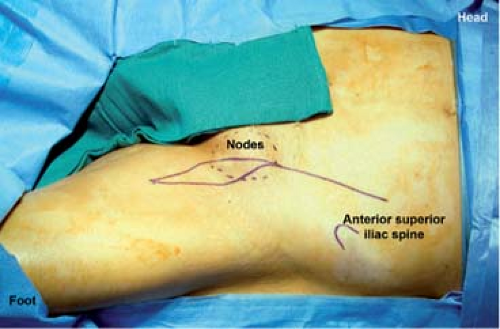

In the case of pelvic lymphadenectomy, exposure can be achieved by extending the vertically oriented incision cephalad to a point 3 to 4 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 1). While this incision does traverse the inguinal crease, division of the inguinal ligament over the femoral vessels affords the potential for an en bloc dissection of both superficial and deep node compartments. This approach also provides excellent access for a more thorough dissection of the most distal external iliac nodes. An alternative to this approach would be a skin crease infrainguinal incision for the superficial groin and a parallel suprainguinal skin crease or transplant-type incision for the deep groin. While these parallel incisions generally heal quite well, the main disadvantage is the relative lack of access to the most distal external iliac nodes.

If a vertically oriented incision is to be utilized, it is important to excise an ellipse of skin overlying the femoral triangle, roughly 3 to 4 cm wide. This shortens the length of flaps that need to be dissected, and dramatically diminishes the likelihood of skin edge necrosis and subsequent superficial wound dehiscence.

Superficial Inguinofemoral Lymphadenectomy

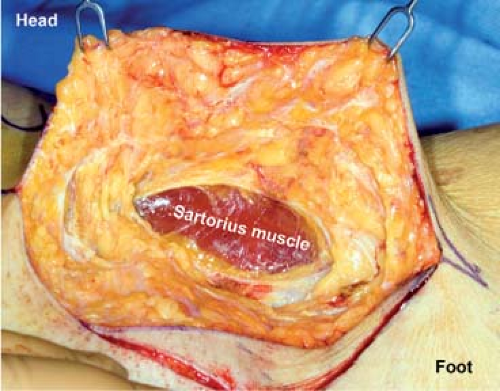

Once the skin incision has been selected and made, skin flaps are raised in the plane just deep to Scarpa’s fascia, circumferentially around the lymph node basin. These flaps should not be too thin, as if so, they will be devascularized, inevitably leading to skin edge necrosis and delayed wound healing. Branches of the saphenofemoral junction with their corresponding arteries are clipped and divided as they are encountered at the periphery of the lymphadenectomy. Flaps are raised laterally to the sartorius muscle (Fig. 2), medially to the adductor magnus muscle, and inferiorly to the point where these two muscles cross, where the saphenous vein is traditionally identified, clamped, divided, and ligated. Superiorly, skin flaps are raised to include 5 to 6 cm of fatty and lymphatic tissue overlying the inguinal ligament, medially to the level of the external ring, where the spermatic cord (or ligamentum teres) is exposed and preserved. The dissection proceeds to the pubic tubercle, then down to the pectineus and adductor magnus muscles (Fig. 3). We prefer to take the fascia of the sartorius, adductor magnus, and pectineus muscles, although the therapeutic value of this maneuver is unknown. Some authors have described

preservation of the muscle fascia to minimize postoperative morbidity; no strong data exist to support or refute either approach.

preservation of the muscle fascia to minimize postoperative morbidity; no strong data exist to support or refute either approach.

Fig. 2. The lateral skin flap is raised first, down to and including the sartorius fascia. Preservation of the fascia is optional. |

At the inferior apex of the femoral triangle, the saphenous vein is encountered. In the classic inguinofemoral dissection, this is clamped, divided, and ligated (Fig. 4). Again, in an effort to decrease postoperative morbidity, a modification of the procedure, which preserves the saphenous vein has been described, and will be discussed below.

Once the skin flaps have been raised, exposure is maintained with a self-retaining retractor (we prefer a Gelpi or Beckman retractor). We then begin dissection of the nodes from the inferior apex of the femoral triangle working cephalad, in the adventitial plane along the superficial femoral artery and vein (Figs. 5 and 6). Care is taken to clip longitudinally oriented lymphatics as they are encountered. Approaching the femoral vessels, the fascia of the adductor and sartorius muscles is once again transected to get into the correct plane. Small arterial branches and venous tributaries are clipped and divided as they are encountered. Working up toward the common femoral vessels, we take the fatty and lymphatic tissue off the inguinal ligament at the lateral aspect of the femoral triangle and dissect this medially off the sartorius muscle. Overly aggressive use of the electrocautery at this point will result in stimulation of the motor branches of the femoral nerve, and should be avoided. The fatty and lymphatic tissues are swept medially off the common femoral artery. At this point, the saphenofemoral junction is identified. This is clamped, divided, and suture ligated (Fig. 7). The lymphatic tissue is then dissected off the medial aspect of the femoral vein, up toward the femoral canal, together with the fascia of the adductor magnus and pectineus muscles. If the procedure is to be concluded, the superficial inguinofemoral contents are removed and submitted for appropriate pathologic examination (Fig. 8).

At this point, the femoral canal is entered, and an attempt made to identify the so-called node of Cloquet. This maneuver starts by inserting a finger through the femoral canal and manually palpating for any enlarged external iliac or obturator nodes. We find that placing a small loop retractor on the inguinal ligament, then reaching under and gently grasping and delivering Cloquet’s node with an Allis clamp works well (Fig. 9). Once removed, Cloquet’s node is submitted for frozen section examination.

While Cloquet’s node may not be a reproducible anatomic entity, the concept is that the lymph node lying within the femoral canal represents a bridging node between the superficial and deep nodal basins. The status of this node has been used by many to guide a decision as to whether or not to proceed to elective deep pelvic node dissection. In melanoma, many, but not all, believe that if this node is positive, there is a significant likelihood of deep pelvic node involvement, and the operation should be extended. On the other hand, if this node is negative, there is a low likelihood of clinically occult pelvic nodal involvement, and the operation may be concluded at this point.

If the procedure is concluded, the incision is closed. The first step is to close the femoral canal, to prevent postoperative femoral hernia. For a secure repair, this involves approximating the inguinal ligament to the lacunar ligament (rather than the pectineus muscle) with one or two interrupted figure-of-eight nonabsorbable sutures (Fig. 10). It is important not to narrow the femoral canal too much with these sutures, to avoid occlusion, and/or thrombosis of the common femoral vein. Closed suction drains are placed to deal with postoperative lymphorrhea (Fig. 11). The incision is then closed in layers. We prefer closely spaced interrupted sutures to Scarpa’s fascia to achieve an airtight closure, followed by either a subcuticular suture or clips to the skin.

Deep Ileo-Obturator Lymphadenectomy

If pelvic lymphadenectomy (ileo-obturator lymphadenectomy) is to be performed, and this is anticipated ahead of time based on imaging studies, Cloquet’s node need not be sampled, and the entire lymph node package, both superficial and deep, can be removed in continuity, by extending the incision cephalad and dividing the inguinal ligament (see below). If the superficial groin contents have been removed previously, then the pelvic nodes can be approached through a suprainguinal skin crease-type incision. That incision should be low enough to enable access to the distal most external iliac nodes, and should be long enough to provide adequate exposure and access to the more proximal pelvic nodes.

If Cloquet’s node is positive on frozen section, and the deep pelvic portion of the lymph node dissection is to be done in continuity, the skin incision is extended cephalad, up toward the a point 3 to 4 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac as described above. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are divided. The fascia of the external oblique muscle is divided lateral to the rectus abdominus muscle in the direction of its fibers, bringing that incision down toward the inguinal ligament at the level of the femoral vessels. Prior to dividing the inguinal ligament, the retroperitoneum is entered. This is done by grasping the internal oblique muscle lateral to the rectus muscle, and dividing it in the direction of the previous incision. An areolar plane is entered just deep to the transversalis fascia. Great care is taken at this point not to violate the peritoneum. The peritoneum and its contents are then bluntly dissected off the undersurface of the transversalis muscle laterally and the femoral vessels in the depth of the incision. We prefer to retract

the inferolateral aspect of the abdominal wall with Kocher clamps to facilitate this access to the retroperitoneum. The incision is then developed more cephalad, dividing the abdominal wall muscles to the level of the anterior superior iliac spine, and caudad down toward the femoral canal. A finger is placed through the femoral canal to protect the femoral vessels as the ligament is divided at this level. At this point, complete exposure of the pelvis can be achieved, as the peritoneum and its contents is bluntly dissected and retracted superomedially. We find that a multiblade self-retaining retractor (Bookwalter, Thompson) at this point is invaluable to provide and maintain exposure (Fig. 12). Deep Richardson-type blades are placed to retract the peritoneum superiorly and medially, to retract the bladder medially, and to retract the abdominal wall laterally. This generally affords excellent exposure to the lower retroperitoneum and pelvis. As with all self-retaining retractors, care must be taken at this point to avoid sustained pressure on the femoral nerve, to prevent postoperative nerve palsy.

the inferolateral aspect of the abdominal wall with Kocher clamps to facilitate this access to the retroperitoneum. The incision is then developed more cephalad, dividing the abdominal wall muscles to the level of the anterior superior iliac spine, and caudad down toward the femoral canal. A finger is placed through the femoral canal to protect the femoral vessels as the ligament is divided at this level. At this point, complete exposure of the pelvis can be achieved, as the peritoneum and its contents is bluntly dissected and retracted superomedially. We find that a multiblade self-retaining retractor (Bookwalter, Thompson) at this point is invaluable to provide and maintain exposure (Fig. 12). Deep Richardson-type blades are placed to retract the peritoneum superiorly and medially, to retract the bladder medially, and to retract the abdominal wall laterally. This generally affords excellent exposure to the lower retroperitoneum and pelvis. As with all self-retaining retractors, care must be taken at this point to avoid sustained pressure on the femoral nerve, to prevent postoperative nerve palsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree