Radical Cystectomy and Orthotopic Urinary Diversion for Bladder Cancer

Eila Skinner

Siamak Daneshmand

Introduction

In the United States, transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder is the second most common malignancy of the genitourinary tract, and the second most common cause of death of all genitourinary tumors. In 2009, there were an estimated 71,000 new cases of bladder cancer diagnosed in the United States (53,000 in men and 18,000 in women), with approximately 14,000 deaths. Approximately 75% of patients with primary transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder present with low-grade tumors confined to the superficial mucosa. The risk of superficial recurrence in patients with bladder tumors confined to the mucosa is 75%, with the majority of these cancers amenable to initial transurethral resection and selected administration of intravesical immunotherapy or chemotherapy. However, 20% to 40% of all patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder will either present with or develop a high-grade, invasive tumor of the bladder. If left untreated, over 85% of patients with high-grade, muscle invasive bladder cancer will die of the disease within 2 years of diagnosis. This clearly underscores a malignant subset of invasive bladder tumors that is most effectively treated by early radical therapy. Radical cystectomy has traditionally been considered the standard of therapy for high-grade, muscle invasive bladder cancer with the best survival results and lowest local recurrence rates.

Invasive bladder tumors tend to progressively invade from their superficial origin in the mucosa to the lamina propria and sequentially into the muscularis propria, perivesical fat, and contiguous pelvic organs, with an increasing incidence of lymph node involvement at each level. Radical cystectomy, with an appropriate lymphadenectomy, provides the optimal result with regard to accurate pathologic staging, prevention of local recurrence, and overall survival.

With improvements over the past several decades in medical, surgical, and anesthetic techniques, the morbidity and mortality associated with radical cystectomy has dramatically decreased. Prior to 1970, the mortality rate of for cystectomy was nearly 20%. This has significantly diminished to less than 2% to 3% perioperative mortality rate reported in contemporary series. In addition, radical cystectomy with an extended pelvic lymphadenectomy provides optimal local control of the tumor. Pelvic recurrence rates in patients undergoing radical cystectomy are <10% for patients with node-negative bladder tumors, and 10% to 20% for patients with resected pelvic nodal metastases.

Lower urinary tract reconstruction with orthotopic diversion has provided an attractive alternative for patients undergoing radical cystectomy, and has allowed some patients and surgeons to consider this surgery earlier in the disease process when it has the best chance of cure. Currently, most men and women can safely undergo orthotopic lower urinary tract reconstruction to the native urethra following cystectomy. Orthotopic reconstruction most closely resembles original bladder function, providing a continent means to store urine and allowing volitional voiding per urethra. It eliminates the need for a cutaneous stoma or urostomy appliance, and in most cases the need for intermittent catheterization. In our experience, most patients chose this option when presented with the pros and cons of each type of diversion.

The authors from the University of Southern California (USC) have made a dedicated effort to continually improve upon the surgical technique of radical cystectomy and to provide an acceptable form of urinary diversion without compromise of a sound cancer operation. Technical issues regarding radical cystectomy and an extended bilateral pelvic iliac lymphadenectomy are critical in order to minimize local recurrence and positive surgical margins and to maximize cancer-specific survival. Attention to surgical detail is critical in optimizing the successful clinical outcomes of orthotopic diversion, maintaining the rhabdosphincter mechanism and urinary continence in these patients.

A growing body of evidence exists to suggest that a more extended lymphadenectomy may be beneficial in both lymph node-positive and lymph node-negative patients with bladder cancer. Although the ideal limits of the lymphadenectomy for patients with bladder cancer undergoing cystectomy are currently debated, we advocate an extended lymph node dissection with the boundaries to include initiation at the level of the inferior mesenteric artery (superior limits of dissection), extending laterally over the inferior vena cava/aorta to the genitofemoral nerve (lateral limits of dissection), and distally to the lymph node of Cloquet. This bilateral dissection should also include all obturator, hypogastric, and presacral lymph nodes.

This chapter will detail the preoperative evaluation, surgical technique, and clinical results and outcomes of radical cystectomy and orthotopic lower urinary tract reconstruction.

The empty bladder is roughly triangular in shape, with only the top covered by peritoneum. It lies within the true pelvis and the extraperitoneal space around the sides is known as the space of Retzius. The detrusor muscle of the bladder is closely covered by the perivesical fat, which can be removed only with some difficulty. In both males and females, the anterior and anterior-lateral bladder lies free of any attachments to the abdominal wall except through the urachal remnant, which extends up to the umbilical scar in the midline. Deep in the pelvis the endopelvic fascia reflects from the pelvic floor up onto the prostate and bladder. A consolidation of this fascia, the puboprostatic ligament, fixes the prostatic apex to the undersurface of the pubic bone. Levator muscle fibers also attach to the prostatic apex posteriorly. A similar but less well-developed ligament extends between the proximal urethra and pubic bone in the female. In the male, the bladder and prostate are essentially fused at the bladder neck, with the transitional mucosal lining of the bladder extending into the prostatic and bulbar urethra without interruption. Posteriorly, the peritoneal reflection behind the bladder and prostate (Pouch of Douglas) extends down as a fusion fascia between the prostate and rectum (Denonvillier’s fascia). Dissection in the plane behind this fascia (Denonvillier’s space) is required to safely separate the prostate off of the rectum. In the female, the bladder lies on the anterior surface of the uterine cervix, with

the peritoneal fold between the two generally not extending all the way down to the vagina. The bladder is quite densely adherent to the anterior vaginal wall, requiring sharp dissection to separate the two structures.

the peritoneal fold between the two generally not extending all the way down to the vagina. The bladder is quite densely adherent to the anterior vaginal wall, requiring sharp dissection to separate the two structures.

The blood supply to the bladder arises from the internal iliac artery and vein, which give off the superior vesicle and inferior vesicle branches. The superior vesicle artery and vein course over the top of the ureter as it enters the detrusor muscle. The inferior vesicle artery arises more inferiorly off of the internal iliac trunk, and together with the superior vesicle vessels make up the lateral pedicle. The anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery terminates in the internal pudendal artery. In the male, the inferior vesicle artery supplies the prostate and bladder neck area. In the female, the uterine artery arises off of the superior vesicle artery and courses similarly over the ureter toward the uterus and cervix. There are additional branches from the middle rectal artery and vein that course around the rectum (and vagina in the female) and supply the bladder neck area (the posterior pedicles). A major venous plexus courses along the lateral bladder in both males and females and can be a source of significant bleeding during cystectomy. A second venous plexus courses anteriorly over the urethra (the dorsal venous complex).

The neurovascular bundle in the male carries parasympathetic fibers along with small vessels from the hypogastric plexus toward the penis, coursing along the groove between the posterior prostate and the rectum. Preservation of this bundle during cystectomy is required if erectile function is to be preserved. A similar bundle courses along the lateral vagina in the female, although the role of these nerves in preserving continence or sexual function is somewhat controversial. The main nervous supply to the external urethral sphincter in both males and females appears to course within the levator muscle fibers in the pelvic floor lateral to the urethra itself.

The lymphatic drainage of the bladder follows the primary vessels, coursing to the obturator, internal iliac, and common iliac chains. However, additional drainage includes the external iliacs and presacral nodes. The drainage appears to be bilateral in most cases. From the pelvic nodes, drainage continues up along the periaortic and peri-caval chains. There is not a single identified “sentinal” node for bladder cancer. Node mapping studies have suggested that the primary landing site is in the internal ileac and obturator areas, but solitary positive nodes can occasionally be found in the presacral and common iliac areas as well.

There are few congenital anomalies of bladder formation. However, some vascular variations that are important include the presence of accessory obturator arteries and veins arising from the external iliac vessels in 40% of patients, and accessory pudendal vessels in males, which may be important in preservation of potency. In addition, conditions such as bladder diverticula and prior pelvic surgeries can impact the ease of dissection. Renal anomalies such as horseshoe kidney, duplicated ureters, and others must be recognized as well.

The vast majority of patients with bladder cancer present with gross painless hematuria. Any patient over age 40 with hematuria necessitates evaluation for bladder cancer. Other presenting symptoms may include irritative symptoms (frequency, urgency, incontinence), which are often misdiagnosed as a urinary tract infection, sometimes delaying diagnosis for months. Symptoms of extravesical involvement include flank pain (from upper tract obstruction), bone pain, cough or hemoptysis, and weight loss.

Smoking is the most significant known risk factor for bladder cancer. Often, patients have quit smoking many years before the diagnosis; however, the risk declines only slightly over decades. Up to 30% of men and 50% of women with this disease have never smoked. Other environmental exposures such as industrial chemicals and dyes have also been identified as etiologic agents.

The evaluation of hematuria is very standardized in any patient over age 40. It should include upper tract imaging (generally a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous [IV] contrast) as well as flexible or rigid cystoscopy. Often an ultrasound or non-contrast CT scan is ordered as a preliminary study as part of an emergency room protocol—these are inadequate evaluations for hematuria, with poor sensitivity for detection of both bladder cancer and small renal masses. The ideal CT scan evaluation should include a non-contrast scan followed by an IV contrast scan including the delayed excretion phase (CT Urogram). In patients with contrast allergy or poor renal function, the upper tracts may be evaluated with ultrasound combined with retrograde pyelography or MRI with gadolinium.

Cystoscopy is mandatory in the evaluation of hematuria because currently available imaging tests have poor sensitivity for small bladder tumors. Cystoscopy is usually performed in the doctor’s office with a flexible or rigid cystoscope under local anesthesia. Papillary tumors are very easily identified on cystoscopy. Carcinoma in situ (CIS) is a flat lesion in the bladder, which has a very aggressive natural history. It may be difficult to identify with cystoscopy, although a patchy, slightly raised erythematous area may be visible. Urinary cytology is nearly always positive in the presence of CIS, and this test is an important adjunct to the initial cystoscopy. Cytology is usually normal in the face of lower grade bladder cancers, so it is not useful alone as a screening test. A number of newer urinary tests are also currently available or in development to diagnose bladder cancer. These are both protein-based tests (NMP22 and BTA Stat) and immumnohistochemical (UroVysion FISH and Immunocyt). However, the ideal use of these tests in both the initial diagnosis and the follow-up of patients with prior bladder cancer is still unclear. No combinations of urinary markers has been proven in clinical studies to be sensitive and specific enough to replace cystoscopy in the initial evaluation of hematuria.

Once a bladder tumor is visualized, the next step is transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) to establish histology and grade as well as depth of invasion. A bimanual examination should also be performed under anesthesia during that resection. This is important for clinical staging (Table 1) and for planning the surgical approach for patients with invasive tumors. For patients with low-grade papillary tumors, no further metastatic workup is necessary. However, patients with high-grade or invasive lesions require a full staging evaluation. Standard evaluation should include a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with IV and oral contrast, along with a bone scan. Contrast is necessary to evaluate the upper tract for synchronous lesions, and also for improved evaluation of the retroperitoneal nodes and liver. For patients who cannot receive IV contrast, MRI with gadolinium can be used to evaluate the abdomen and pelvis. Recently, PET scans have been used for staging, but both false negatives and false positives have been seen. It is not yet clear that there is any advantage of FDG-PET over standard contrast-enhanced CT or MRI for staging the localized tumor or metastatic disease.

Despite recent advances in radiographic imaging techniques, errors in clinical staging of the primary bladder tumor are very common. Patients with hydronephrosis, a palpable mass on bimanual examination, or clear extravesical extension on preoperative

imaging generally will have pT3 or greater disease on final pathology (even if clear muscle invasion has not been documented on transurethral biopsy). Table 2 shows the discrepancy between clinical and final pathologic stages for a contemporary group of patients undergoing cystectomy.

imaging generally will have pT3 or greater disease on final pathology (even if clear muscle invasion has not been documented on transurethral biopsy). Table 2 shows the discrepancy between clinical and final pathologic stages for a contemporary group of patients undergoing cystectomy.

Table 1 AJCC TNM Staging System for Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The treatment of bladder cancer should be adjusted for the risk of the tumor to recur and/or progress. In general low-grade, Ta lesions are treated with endoscopic transurethral resection alone. A single dose of intravesical chemotherapy (with doxorubacin or mitomycin C or other agent) may be instilled immediately following the resection to reduce tumor implantation on the resected raw surface of the bladder. Additional intravesical therapy is indicated for patients with large or multifocal tumors, or those with frequent recurrences.

Table 2 Discrepancy Between Clinical and Pathological Staging in Patients Undergoing Cystectomy by Clinical Stage | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Patients with high-grade tumors that are non-muscle-invasive (stage Ta or T1) and CIS are at significantly higher risk of recurrence and progression to muscle-invasive disease. Intravesical therapy is mandatory for these patients, and immunotherapy using BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, a live attenuated strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis) has been the most effective intravesical agent. Usually 6 weekly instillations are administered, with variable use of maintenance therapy thereafter. Re-induction may be used for later recurrences.

The long-term risk of progression to muscle-invasive disease or metastasis for these high-risk tumors treated with intravesical therapy may be as high as 50% to 70%, especially high-grade T1 tumors with invasion into the lamina propria. For this reason, cystectomy may be a reasonable option for the younger, healthy patients with high-grade T1 tumor, especially with known risk factors for progression such as large tumors, associated CIS, or deep lamina propria invasion. Patients with high-grade tumors who are considered for intravesical therapy should generally undergo repeat transurethral resection, which will detect occult muscle-invasive tumor in a significant percentage.

Patients with high-grade disease who fail intravesical therapy and any patient with localized muscle-invasive disease should be considered for cystectomy, with or without systemic chemotherapy. A timely approach to surgery has shown to be important, with negative impact if surgery is delayed more than 12 weeks past diagnosis of muscle-invasive disease. Patients who are not reasonable surgical candidates or who refuse surgery may be treated with external beam radiation therapy, usually with concomitant systemic chemotherapy. Although radiation therapy is popular in many other parts of the world, it has been much less often used in the United States as primary local therapy for bladder cancer. The advantages of cystectomy over radiation therapy include the ability to obtain accurate pathologic staging, better local tumor control, and better long-term disease-free rates. Salvage cystectomy is feasible after failure of local radiation therapy, but it is technically challenging, has higher complication rates, and is generally less amenable to efforts for nerve-sparing and orthotopic neobladder reconstruction. A randomized trial comparing surgery and radiation has not been performed.

Many patients with aggressive bladder cancers are very elderly with significant comorbidities. These cancers will usually progress to metastasis and death within 2 years of diagnosis, causing significant misery from bleeding, pain, and obstruction from the local bladder tumor if the bladder is not removed. Therefore, an elderly patient who is believed to have at least a 2-year life expectancy and is likely to survive the surgery should be considered for cystectomy regardless of his or her chronological age.

Systemic chemotherapy using a cisplatin-based combination is often administered in combination with cystectomy for patients with invasive bladder cancer who are at high risk of occult metastatic disease. Surgery alone achieves long-term cure in approximately 50% to 70% of patients with invasive bladder cancer. Pathologic stage is the strongest predictor for survival. A number of other factors have been shown to be prognostic indicators, including age and gender, the presence of lymphovascular invasion, and genetic markers in the tumor such as p53 tumor suppressor gene mutation. Systemic chemotherapy may be administered prior to surgery (neoadjuvant treatment) or following recovery from the operation (adjuvant). A randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant MVAC chemotherapy plus surgery to surgery alone for patients with T2-T4 disease showed a survival advantage for those who received chemotherapy.

Because of the inaccuracy of clinical staging and a worry about the delay in surgery in patients who do not respond to chemotherapy, many urologic oncologists have preferred to use chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting for patients with extravesical disease only. Clinical trials with adjuvant treatment have been mixed, with some trials showing an advantage and others not. Only one small trial directly compared neoadjuvant to adjuvant therapy, and that trial showed no difference in outcome. Many of these studies have been underpowered to detect significant differences.

Experience has shown that neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery is somewhat better tolerated than using chemotherapy administered postoperatively in these older patients. Few patients are unable to undergo the surgery due to complications of chemotherapy, and we have not seen a dramatic increase in surgical complications in this setting. On the other hand, an elderly patient who suffers a serious complication from the surgery may not be well enough to receive systemic chemotherapy within 2 to 3 months of the operation.

Based on the evidence to date, a consultation with a medical oncologist to discuss neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be strongly considered for any patient with muscle-invasive disease prior to cystectomy. Patients with a palpable pelvic mass on bimanual exam, hydronephrosis, or apparent extravesical disease on CT scan should nearly always receive neoadjuvant therapy since they are unlikely to have organ-confined disease. In addition, patients with divergent histological patterns including the presence of neuroendocrine differentiation or micropapillary pattern should also be treated with initial chemotherapy. Patients who have not received preoperative chemotherapy and have extravesical or node-positive disease on final pathology should be considered for adjuvant chemotherapy, usually begun 6 to 8 weeks following surgery.

Indications for Radical Cystectomy

The primary indications for cystectomy are the presence of localized high-grade disease with muscle-invasion or high-grade non-muscle-invasive disease or CIS that has failed intravesical therapy. Young patients with high-grade non-muscle-invasive disease that is multifocal or associated with CIS or lymphovascular invasion may be offered primary cystectomy as an alternative to initial intravesical therapy due to high progression rates. Cystectomy is rarely recommended in the treatment of low-grade disease unless a concerted effort at endoscopic management has failed. Cancer-free patients will occasionally require cystectomy because of severe bladder dysfunction resulting from intravesical therapy or pelvic radiation therapy. Patients with metastatic urothelial cancer occasionally require palliative cystectomy to manage severe bleeding, pain, or urinary obstruction.

Table 3 Contraindications for Orthotopic Diversion | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Indications for Orthotopic Diversion

Orthotopic urinary diversion is offered to nearly all patients undergoing cystectomy in our practice unless they have a specific contraindication (Table 3), regardless of age. The advantages and disadvantages of each form of diversion are discussed in an attempt to help the patient make a choice that fits his or her own priorities and lifestyle. Every form of diversion has an impact on the patient’s quality of life and carries a risk of specific complications, and there is no strong evidence that the overall quality of life is better for patients with one diversion or another. However, a considerable body of evidence has shown that continent diversion in the hands of an experienced surgical team does not increase hospital stay or early postoperative complications compared to ileal conduit. Orthotopic diversion has the specific advantage of allowing the most “natural” form of voiding without the need for an appliance. The vast majority of patients with time achieve daytime continence, and approximately half of them are dry at night. In men, advanced age appears to delay the achievement of continence but does not otherwise affect outcome. Elderly women do appear to have a higher risk of permanent incontinence compared to younger women. Patients sometimes need to do self-catheterization (more often in women than in men), so any patient considering an orthotopic neobladder should be willing and able to perform this. Late complications such as stones and anastomotic strictures can generally be managed with endoscopic techniques.

Table 4 Perioperative Mortality and Early Complication Rates in 1,054 Patients Who Underwent Radical Cystectomy for Transitional Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Risk of Urethral Recurrence

In men who have undergone cystectomy and orthotopic diversion, the presence of prostatic urethral involvement with urothelial carcinoma increases the risk of late urethral recurrence. In our series, the risk of urethral recurrence at 5 years was 5% for patients without any prostatic involvement compared to 11% with any involvement. The risk went up to 18% for patients with invasion of tumor into the prostatic stroma. Thus, in a patient with prostatic urethral involvement documented preoperatively the decision whether or not to perform an orthotopic diversion must be made with this risk in mind. A negative intraoperative frozen section of the prostatic apical urethral mucosa is the final requirement that must be met prior to constructing an orthotopic diversion.

For women, the risk of urethral involvement is primarily driven by tumor location. Tumors located at the bladder neck or associated with palpable invasion into the anterior vaginal wall are associated with a high risk of urethral involvement and are a relative contraindication to neobladder diversion. In many cases, we depend on the negative frozen section of the proximal urethra at the time of surgery to make a final decision.

Locally Advanced Disease

Many urologists are hesitant to perform continent orthotopic diversion in patients with locally extensive disease. This is based on two factors: (a) concern about the possible impact of local recurrence on the neobladder itself, and (b) a belief that these patients are doomed to suffer distant recurrence and have a shortened life expectancy and will not benefit from the neobladder. However, in our series of over 2,000 patients undergoing cystectomy, <7% of patients suffered a local recurrence with a median follow-up of over 10 years. We and others have observed that patients who do develop a pelvic recurrence rarely have problems with direct tumor invasion into the reservoir causing symptoms. Thus, this form of diversion appears to be an option even with locally extensive disease, especially if one can achieve a grossly negative margin.

Effect of Prior Radiation Therapy

It is not uncommon for patients with invasive bladder cancer to have a history of

prior radiation therapy for other pelvic malignancies. Bochner and associates described our initial experience with salvage surgery and orthotopic bladder substitution after failed radical radiation therapy. Our initial 18 male patients who had failed definitive radiation therapy (total minimum dose, 60 Gy or greater) for bladder or prostate cancer and had undergone a salvage procedure with construction of an orthotopic neobladder were evaluated. Good daytime and nighttime continence after surgery was reported by 67% and 56% of irradiated patients, respectively. Patients with poor postoperative continence (22%) were successfully treated with the placement of an artificial urinary sphincter. Others have reported similar results with small series of patients. Again, intraoperative assessment is crucial to determine the health of the urethral tissue and the advisability of performing an orthotopic diversion.

prior radiation therapy for other pelvic malignancies. Bochner and associates described our initial experience with salvage surgery and orthotopic bladder substitution after failed radical radiation therapy. Our initial 18 male patients who had failed definitive radiation therapy (total minimum dose, 60 Gy or greater) for bladder or prostate cancer and had undergone a salvage procedure with construction of an orthotopic neobladder were evaluated. Good daytime and nighttime continence after surgery was reported by 67% and 56% of irradiated patients, respectively. Patients with poor postoperative continence (22%) were successfully treated with the placement of an artificial urinary sphincter. Others have reported similar results with small series of patients. Again, intraoperative assessment is crucial to determine the health of the urethral tissue and the advisability of performing an orthotopic diversion.

Patients undergoing cystectomy often have significant comorbidities, especially heart and lung dysfunction related to smoking. Preoperative optimization is crucial in making this a safe operation. Most patients are evaluated preoperatively by a cardiologist and we routinely employ the use of provocative cardiac testing (stress echocardiogram or similar tests) and pulmonary function testing when indicated to assist in perioperative management. In the past, we have used mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation beginning 24 hours prior to surgery in these patients, since the small bowel is widely opened as it is refashioned into the neobladder. The right colon may also be opened to use as a continent cutaneous reservoir in the occasion that the urethra is not usable. However, recent data has implicated the bowel preparation in some postoperative complications such as Clostridium difficile bacterial colitis and prolonged ileus. We and many other groups have recently avoided using a full bowel preparation, using instead a clear liquid diet and mild laxative the evening prior to surgery. The most frail, elderly patients are admitted for IV hydration the night before surgery to avoid some of the fluid shifts during the operation. All patients receive perioperative antibiotics according to the recommendations of the AUA Guidelines Committee.

We are fortunate to have a dedicated enterostomal therapist on our team who meets with each patient preoperatively to go over expectations for the perioperative period. He or she also marks the patient for a possible ileal conduit diversion in case that should become necessary during the surgery. We also have a set of written instructions that patients receive going over management of catheters and drains, Kegel exercise techniques, and techniques for self-catheterization. The ideal cutaneous stoma site is determined only after the patient is examined in the supine, sitting, and standing position. In general, incontinent stoma sites are best located higher on the abdominal wall, while stoma sites for a continent cutaneous diversion can be positioned lower on the abdomen (hidden below the belt line) since they do not require an external collecting device. The use of the umbilicus as the site for catheterization may be employed with excellent functional and cosmetic results.

Minimally Invasive Surgical Approaches to Cystectomy and Ileal Neobladder

In recent years, laparoscopic and robot-assisted laparoscopic techniques have been applied to radical cystectomy, with somewhat mixed results. Completing a thorough extended pelvic and ileal lymphadenectomy using these techniques is challenging and can be very time-consuming. Nearly all surgeons doing laparoscopic or robotic cystectomies now perform an extracorporeal neobladder through a small suprapubic incision to facilitate the bowel work.

Most reports of minimally invasive cystectomies show a decreased blood loss compared to open series, and a few have shown shorter hospital stay. However, at least one group of experienced robotic surgeons who were trained and committed to performing an extended lymphadenectomy found very similar complication rates and hospital stay to our open series. Thus, the advantage of the extended operative time and increased cost associated with use of the robot is still unclear. It is likely, however, that any limitation of the extent of dissection for the bladder and lymph nodes to allow easier minimally invasive surgery will translate to a worse long-term oncologic outcome.

Radical Cystectomy and Extended Lymphadenectomy: Surgical Technique in the Male and Female Patients

Extent of Lymphadenectomy

There is general agreement that a pelvic lymphadenectomy is an important part of any radical cystectomy performed for bladder cancer. However, there is some controversy about the proper extent of the lymphadenectomy. The primary lymphatic drainage of the bladder includes the obturator, external iliac and internal iliac nodes, and most authors have included these nodes in a “standard” pelvic node dissection. We have routinely performed a more extended dissection including the nodes overlying the distal aorta and vena cava along with the presacral nodal package. Although no randomized study has been performed to test this question, there is indirect evidence that a more extensive dissection may be beneficial to both patients with positive and negative nodes.

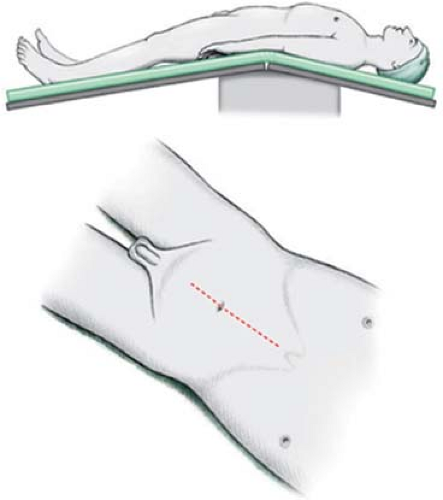

Patient Positioning

The patient is placed in the hyperextended supine position with the iliac crest located just below the fulcrum of the operating table (Fig. 1). The legs are slightly abducted so that the heels are positioned near the corners of the foot of the table. In the female patient considering orthotopic diversion, the modified frog leg or lithotomy position is employed allowing access to the vagina. Care should be taken to ensure that all pressure points are well padded. Reverse Trendelenburg position levels the abdomen parallel with the floor and helps to keep the small-bowel contents in the epigastrium. A nasogastric tube is placed, and the patient is prepped from nipples to midthigh. In the female patient, the vagina is fully prepped. After the patient is draped, a 16-French Foley catheter is placed in the bladder and left open to gravity. A right-handed surgeon stands on the patient’s left-hand side of the operating table.

Incision

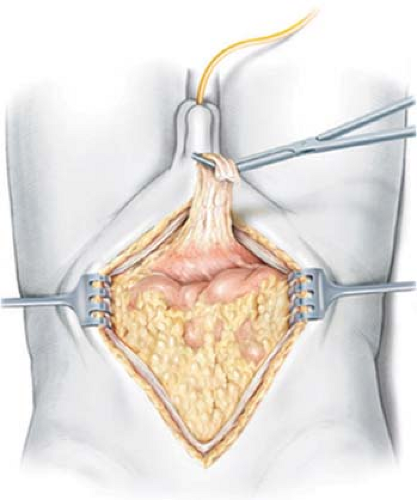

A vertical midline incision is made extending from the pubic symphysis to just above the umbilicus. The incision should be carried lateral to the umbilicus on the contralateral side of the marked cutaneous stoma site. When considering the umbilicus as the site for a catheterizable stoma, the incision should be directed 2 to 3 cm lateral to the umbilicus at this location. The anterior rectus fascia is incised, the rectus muscles retracted laterally, and the posterior rectus sheath and peritoneum entered in the superior aspect of the incision. As the peritoneum and posterior fascia are incised inferiorly to the level of the umbilicus, the urachal remnant (median umbilical ligament) is identified, circumscribed, and kept attached to the bladder (Fig. 2). This maneuver prevents early entry into a high-riding bladder and ensures complete removal of all bladder

remnant tissue. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the inferior epigastric vessels, which course posterior to the rectus muscles. If the patient has had a previous cystotomy or segmental cystectomy, the cystotomy tract and cutaneous incision should be circumscribed full thickness and excised en bloc with the bladder specimen. The medial insertion of the rectus muscles attachments to the pubic symphysis can be slightly incised, maximizing pelvic exposure throughout the operation.

remnant tissue. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the inferior epigastric vessels, which course posterior to the rectus muscles. If the patient has had a previous cystotomy or segmental cystectomy, the cystotomy tract and cutaneous incision should be circumscribed full thickness and excised en bloc with the bladder specimen. The medial insertion of the rectus muscles attachments to the pubic symphysis can be slightly incised, maximizing pelvic exposure throughout the operation.

Abdominal Exploration

A careful systematic intra-abdominal exploration is performed to determine the extent of disease and to evaluate for any hepatic metastases or gross retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. The abdominal viscera are palpated to detect any concomitant unrelated disease. If no contraindication exists at this time, all adhesions should be incised and freed.

Bowel Mobilization

The bowels are mobilized starting with the right (ascending) colon. The cecum and ascending colon are reflected medially to allow incision of the lateral peritoneal reflection along the avascular/white line of Toldt. The mesentery to the small bowel is then mobilized off the retroperitoneal attachments in a cephalad direction (toward the ligament of Treitz) until the retroperitoneal portion of the duodenum is exposed. Combined sharp and blunt dissection facilitates mobilization of this mesentery along a characteristic avascular fibroareolar plane. Conceptually, the mobilized mesentery forms an inverted right triangle, the base formed by the third and fourth portions of the duodenum, the right edge represented by the white line of Toldt along the ascending colon, the left edge represented by the medial portion of the sigmoid and descending colonic mesentery, and the apex represented by the ileocecal region (Fig. 3). This mobilization is critical in setting up the operative field and facilitates proper packing of the intra-abdominal contents into the epigastrium.

The left colon and sigmoid mesentery are then mobilized by incising the peritoneum lateral to the colon along the avascular/white line of Toldt. The sigmoid mesentery is then elevated off the sacrum, iliac vessels, and Gerota’s fascia, and distal aorta cephalad to the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery. A window is made in the mesentery of the sigmoid colon over the left common iliac vessels to provide a passageway for the left ureter to pass to the right side (without angulation or tension). This also facilitates access to the superior limits of the lymph node dissection (Fig. 4). Care should be taken to dissect along the base of the mesentery and avoid injury to the inferior mesenteric artery and blood supply to the sigmoid colon.

Fig. 2. Wide excision of the urachal remnant en bloc with the cystectomy specimen. (From Stein JP, Skinner DG. Surgical atlas-radical cystectomy. Br J Urol Int 2004;94:197.) |

Following mobilization of the bowel, a self-retaining retractor is placed. The right colon and small intestine are carefully packed into the epigastrium under moist lap pads,

The descending and sigmoid colon are not packed and are left as free as possible, providing the necessary mobility required for the ureteral and pelvic lymph node dissection.

The descending and sigmoid colon are not packed and are left as free as possible, providing the necessary mobility required for the ureteral and pelvic lymph node dissection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree