R

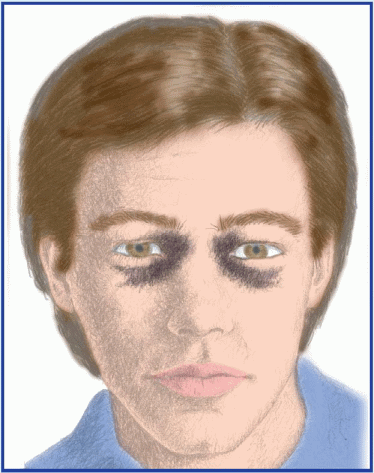

Raccoon eyes

Raccoon eyes are bilateral periorbital ecchymoses that don’t result from facial soft-tissue trauma. Usually an indicator of basilar skull fracture, this sign develops when damage at the time of fracture tears the meninges and causes the venous sinuses to bleed into the arachnoid villi and the cranial sinuses. Raccoon eyes may be the only indicator of a basilar skull fracture, which isn’t always visible on skull X-rays. Their appearance signals the need for careful assessment to detect any underlying trauma because a basilar skull fracture can injure cranial nerves, blood vessels, and the brain stem. Raccoon eyes can also occur after a craniotomy if the surgery causes a meningeal tear.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After raccoon eyes are detected, check the patient’s vital signs and try to find out when the head injury occurred and the nature of the head injury. (See Recognizing raccoon eyes.) Then evaluate the extent of underlying trauma.

Start by evaluating the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC) using the Glasgow Coma Scale. (See Using the Glasgow Coma Scale, page 422.) Next, evaluate function of the cranial nerves, especially the first (olfactory), third (oculomotor), fourth (trochlear), sixth (abducens), and seventh (facial). If the patient’s condition permits, test his visual acuity and gross hearing. Note any irregularities in the facial or skull bones, as well as any swelling, localized pain, a Battle’s sign, or lacerations of the face or scalp. Check for ecchymoses over the mastoid bone. Inspect for hemorrhage or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage from the nose or ears.

Test any drainage with a gauze pad, and note whether you find a halo sign—a circle of clear fluid that surrounds a bloody center, indicating CSF. Use a glucose reagent stick to test any clear drainage for glucose. A positive test result indicates CSF, because mucus doesn’t contain glucose.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Basilar skull fracture. This injury produces raccoon eyes after head trauma that doesn’t involve the orbital area. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the fracture site and may include pharyngeal hemorrhage, epistaxis, rhinorrhea, otorrhea, and a bulging tympanic membrane from blood or CSF. The patient may experience difficulty hearing, headache, nausea, vomiting, cranial nerve palsies, and altered LOC. He may also exhibit a positive Battle’s sign.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Surgery. Raccoon eyes occurring after craniotomy may indicate a meningeal tear and bleeding into the sinuses.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Keep the patient on complete bed rest. Perform frequent neurologic evaluations to reevaluate

his LOC. Check vital signs hourly; be alert for such changes as bradypnea, bradycardia, hypertension, and fever. To avoid worsening a dural tear, instruct the patient not to blow his nose, cough vigorously, or strain. If otorrhea or rhinorrhea is present, don’t attempt to stop the flow. Instead, place a sterile, loose gauze pad under the nose or ear to absorb the drainage. Monitor the amount and test it with a glucose reagent strip to confirm or rule out CSF leakage.

his LOC. Check vital signs hourly; be alert for such changes as bradypnea, bradycardia, hypertension, and fever. To avoid worsening a dural tear, instruct the patient not to blow his nose, cough vigorously, or strain. If otorrhea or rhinorrhea is present, don’t attempt to stop the flow. Instead, place a sterile, loose gauze pad under the nose or ear to absorb the drainage. Monitor the amount and test it with a glucose reagent strip to confirm or rule out CSF leakage.

Recognizing raccoon eyes

It’s usually easy to differentiate raccoon eyes from the “black eye” associated with facial trauma. Raccoon eyes (shown below) are always bilateral. They develop 2 to 3 days after a closed-head injury that results in basilar skull fracture. In contrast, the periorbital ecchymosis that occurs with facial trauma can affect one eye or both. It usually develops within hours of injury.

|

To prevent further tearing of the mucous membranes and infection, never suction or pass a nasogastric tube through the patient’s nose. Observe the patient for signs and symptoms of meningitis, such as fever and nuchal rigidity, and expect to administer a prophylactic antibiotic.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as a computed tomography scan. If the dural tear doesn’t heal spontaneously, contrast cis-ternography may be performed to locate the tear, possibly followed by corrective surgery.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Raccoon eyes in children are usually caused by a basilar skull fracture after a fall.

Rebound tenderness

[Blumberg’s sign]

A reliable indicator of peritonitis, rebound tenderness is intense, elicited abdominal pain caused by rebound of palpated tissue. The tenderness may be localized, as in an abscess, or generalized, as in perforation of an intraabdominal organ. Rebound tenderness usually occurs with abdominal pain, tenderness, and rigidity. When a patient has sudden, severe abdominal pain, this symptom is usually elicited to detect peritoneal inflammation.

If you elicit rebound tenderness in a patient who’s experiencing constant, severe abdominal pain, quickly take his vital signs. Insert a large-bore I.V. catheter, and begin administering I.V. fluids. Also insert an indwelling urinary catheter, and monitor intake and output. Give supplemental oxygen as needed, and continue to monitor the patient for signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia.

If you elicit rebound tenderness in a patient who’s experiencing constant, severe abdominal pain, quickly take his vital signs. Insert a large-bore I.V. catheter, and begin administering I.V. fluids. Also insert an indwelling urinary catheter, and monitor intake and output. Give supplemental oxygen as needed, and continue to monitor the patient for signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient’s condition permits, ask him to describe the events that led up to the tenderness. Does movement, exertion, or any other activity relieve or aggravate the tenderness? Also, ask about other signs and symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, fever, or abdominal bloating or distention. Inspect the abdomen for distention, visible peristaltic waves, and scars. Then auscultate for bowel sounds and characterize their motility. Palpate for associated rigidity or guarding and percuss the abdomen noting any tympany. (See Eliciting rebound tenderness, page 590.)

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Peritonitis. With this life-threatening disorder, rebound tenderness is accompanied by sudden and severe abdominal pain, which may be either diffuse or localized. Because movement worsens the patient’s pain, he’ll usually lie still on his back with his knees flexed. Typically, he’ll display weakness, pallor, excessive sweating, and cold skin. He may

also display hypoactive or absent bowel sounds; tachypnea; nausea and vomiting; abdominal distention, rigidity and guarding; positive psoas and obturator signs; and a fever of 103° F (39.4° C) or higher. Inflammation of the diaphragmatic peritoneum may cause shoulder pain and hiccups.

also display hypoactive or absent bowel sounds; tachypnea; nausea and vomiting; abdominal distention, rigidity and guarding; positive psoas and obturator signs; and a fever of 103° F (39.4° C) or higher. Inflammation of the diaphragmatic peritoneum may cause shoulder pain and hiccups.

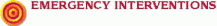

Eliciting rebound tenderness

To elicit rebound tenderness, help the patient into a supine position and push your fingers deeply and steadily into his abdomen (as shown). Then quickly release the pressure. Pain that results from the rebound of palpated tissue—rebound tenderness—indicates peritoneal inflammation or peritonitis.

|

You can also elicit this symptom on a miniature scale by percussing the patient’s abdomen lightly and indirectly (as shown). Better still, simply ask the patient to cough. This allows you to elicit rebound tenderness without having to touch the patient’s abdomen and may also increase his cooperation because he won’t associate exacerbation of his pain with your actions.

|

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Promote comfort by having the patient flex his knees or assume semi-Fowler’s position. You may administer an analgesic, an antiemetic, and an antipyretic. However, because of decreased intestinal motility and the probability that the patient will have surgery, don’t give oral drugs or fluids. Obtain samples of blood, urine, and feces for laboratory testing, and prepare the patient for chest and abdominal X-rays, ultrasounds and computed tomography scans. Perform a rectal or pelvic examination. Prepare the patient to receive an antibiotic, have a nasogastric tube inserted, to maintain a nothing-by-mouth status and to receive continuous parenteral fluid or nutrition.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Eliciting rebound tenderness may be difficult in young children. Be alert for such clues as an anguished facial expression or intensified crying. When you elicit this symptom, use assessment techniques that produce minimal tenderness. For example, have the child hop or jump to allow tissue to rebound gently and watch as the child clutches at the furniture in pain.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Rebound tenderness may be diminished or absent in elderly patients.

Rectal pain

A common symptom of anorectal disorders, rectal pain is discomfort that arises in the anorectal area. Although the anal canal is separated from the rest of the rectum by the internal sphincter, the patient may refer to all local pain as rectal pain.

Because the mucocutaneous border of the anal canal and the perianal skin contains somatic nerve fibers, lesions in this area are especially painful. This pain may result from or be aggravated by diarrhea, constipation, or passage of hardened stools. It may also be aggravated by intense pruritus and continued scratching associated with drainage of mucus, blood, or fecal matter that irritates the skin and nerve endings.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If your patient reports rectal pain, inspect the area for bleeding; abnormal drainage such as pus; or protrusions, such as skin tags or thrombosed hemorrhoids. Check for inflammation and other lesions. A rectal examination may be necessary.

After examination, proceed with your evaluation by taking the patient’s history. Ask the patient to describe the pain. Is it sharp or dull, burning or knifelike? How often does it occur? Ask if the pain is worse during or immediately after defecation. Does the patient avoid having bowel movements because of anticipated pain? Find out what alleviates the pain.

Be sure to ask appropriate questions about the development of any associated signs and symptoms. For example, does the patient experience bleeding along with rectal pain? If so, find out how frequently this occurs and whether the blood appears on the toilet tissue, on the surface of the stool, or in the toilet bowl. Is the blood bright or dark red? Ask whether the patient has noticed other drainage, such as mucus or pus, and whether he’s experiencing constipation or diarrhea. Ask when he last had a bowel movement. Obtain a dietary history.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Abscess (perirectal). This abscess can occur in various locations in the rectum and anus, causing pain in the perianal area. Typically, a superficial abscess produces constant, throbbing local pain that’s exacerbated by sitting or walking. The local pain associated with a deeper abscess may begin insidiously, often high in the rectum or even in the lower abdomen, and is accompanied by an indurated anal mass. The patient may also develop associated signs and symptoms, such as fever, malaise, anal swelling and inflammation, purulent drainage, and local tenderness.

♦ Abscess (prostatic). This disorder occasionally produces rectal pain. Common associated findings include urine retention and frequency, dysuria, and fever. A rectal examination may reveal prostatic tenderness and gas.

♦ Anal fissure. This longitudinal crack in the anal lining causes sharp rectal pain on defecation. The patient typically experiences a burning sensation and gnawing pain that can continue up to 4 hours after defecation. Fear of provoking this pain may lead to acute constipation. The patient may also develop anal pruritus and extreme tenderness and may report finding spots of blood on the toilet tissue after defecation.

♦ Anorectal fistula. Pain develops when a tract formed between the anal canal and skin temporarily seals. It persists until drainage resumes. Other chief complaints include pruritus and drainage of pus, blood, mucus, and occasionally stool.

♦ Cryptitis. This disorder results when particles of stool that are lodged in the anal folds decay and cause infection, which may produce dull anal pain or discomfort and anal pruritus.

♦ Hemorrhoids. Thrombosed or prolapsed hemorrhoids cause rectal pain that may worsen during defecation and abate after it. The patient’s fear of provoking the pain may lead to constipation. Usually, rectal pain is accompanied by severe itching. Internal hemorrhoids may also produce mild, intermittent bleeding that characteristically occurs as spotting on the toilet tissue or on the stool surface. External hemorrhoids are visible outside the anal sphincter.

♦ Proctalgia fugax. With this disorder, muscle spasms of the rectum and pelvic floor produce sudden, severe episodes of rectal pain that last up to several minutes and then disappear. The patient may report being awakened by the pain, which is sometimes associated with stress or anxiety and relieved by food and drink.

♦ Rectal cancer. Rectal pain, bleeding, tenesmus, and a hard, nontender mass are typical findings in this rare form of cancer.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Anal intercourse. Shearing forces may cause inflammation or tearing of the mucous membranes and discomfort.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Apply analgesic ointment or suppositories, and administer a stool softener if needed. If the rectal pain results from prolapsed hemorrhoids, apply cold compresses to help shrink protruding hemorrhoids, prevent thrombosis, and reduce pain. If the patient’s condition permits, place him in Trendelenburg’s position with his buttocks elevated to further relieve pain.

You may have to prepare the patient for an anoscopic examination and proctosigmoidoscopy to determine the cause of rectal pain. He may also need to provide a stool sample. Because the patient may feel embarrassed by treatments and diagnostic tests involving the rectum, provide emotional support and as much privacy as possible.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Observe any child with rectal pain for associated bleeding, drainage, and signs of infection (fever and irritability). Acute anal fissure is a common cause of rectal pain and bleeding in children, whose fear of provoking the pain may lead to constipation. Infants who seem to have pain on defecation should be evaluated for congenital anomalies of the rectum. Consider the possibility of sexual abuse in all children who complain of rectal pain.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Because elderly people typically underreport their symptoms and have an increased risk of neoplastic disorders, they should always be thoroughly evaluated.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Teach the patient how to apply hot, moist compresses. Teach him how to give himself a sitz bath; this will ease his discomfort by helping to relieve the sphincter spasm associated with most anorectal disorders. Stress the importance of following a high-fiber diet and drinking plenty of fluids to maintain soft stools and thus avoid aggravating pain during defecation.

Respirations, grunting

Characterized by a deep, low-pitched grunting sound at the end of each breath, grunting respirations are a chief sign of respiratory distress in infants and children. They may be soft and heard only on auscultation, or loud and clearly audible without a stethoscope. Typically, the intensity of grunting respirations reflects the severity of respiratory distress. The grunting sound coincides with closure of the glottis, an effort to increase end-expiratory pressure in the lungs and prolong alveolar gas exchange, thereby enhancing ventilation and perfusion.

Grunting respirations indicate intrathoracic disease with lower respiratory involvement. Though most common in children, they sometimes occur in adults who are in severe respiratory distress. Whether they occur in children or adults, grunting respirations demand immediate medical attention. (See Positioning an infant for chest physical therapy, pages 594 and 595.)

If the patient exhibits grunting respirations, quickly place him in a comfortable position and check for signs of respiratory distress: wheezing; tachypnea (a minimum respiratory rate of 60 breaths/minute in infants, 40 breaths/minute in children ages 1 to 5, 30 breaths/minute in children older than age 5, or 20 breaths/minute in adults); accessory muscle use; substernal, subcostal, or intercostal retractions; nasal flaring; tachycardia (a minimum of 160 beats/minute in infants, 120 to 140 beats/minute in children ages 1 to 5, 120 beats/minute in children older age 5, or 100 beats/minute in adults); cyanotic lips or nail beds; hypotension (less than 80/40 mm Hg in infants, less than 80/50 mm Hg in children ages 1 to 5, less than 90/55 mm Hg in children older than age 5, or less than 90/60 mm Hg in adults); and decreased level of consciousness.

If the patient exhibits grunting respirations, quickly place him in a comfortable position and check for signs of respiratory distress: wheezing; tachypnea (a minimum respiratory rate of 60 breaths/minute in infants, 40 breaths/minute in children ages 1 to 5, 30 breaths/minute in children older than age 5, or 20 breaths/minute in adults); accessory muscle use; substernal, subcostal, or intercostal retractions; nasal flaring; tachycardia (a minimum of 160 beats/minute in infants, 120 to 140 beats/minute in children ages 1 to 5, 120 beats/minute in children older age 5, or 100 beats/minute in adults); cyanotic lips or nail beds; hypotension (less than 80/40 mm Hg in infants, less than 80/50 mm Hg in children ages 1 to 5, less than 90/55 mm Hg in children older than age 5, or less than 90/60 mm Hg in adults); and decreased level of consciousness.If you detect any of these signs, monitor oxygen saturation, and administer oxygen and prescribed medications such as a bronchodilator. Have emergency equipment available and prepare to intubate the patient if necessary. Obtain arterial blood gas analysis to determine oxygenation status.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After addressing the child’s respiratory status, ask his parents when the grunting respirations began. If the patient is a premature infant, find out his gestational age. Ask the parents if anyone in the home has recently had an upper

respiratory tract infection. Has the child had signs and symptoms of such an infection, such as a runny nose, cough, low-grade fever, or anorexia? Does he have a history of frequent colds or upper respiratory tract infections? Does he have a history of respiratory syncytial virus? Ask the parents to describe changes in the child’s activity level or feeding pattern to determine if the child is lethargic or less alert than usual.

respiratory tract infection. Has the child had signs and symptoms of such an infection, such as a runny nose, cough, low-grade fever, or anorexia? Does he have a history of frequent colds or upper respiratory tract infections? Does he have a history of respiratory syncytial virus? Ask the parents to describe changes in the child’s activity level or feeding pattern to determine if the child is lethargic or less alert than usual.

Begin the physical examination by auscultating the lungs, especially the lower lobes. Note diminished or abnormal sounds, such as crackles or sibilant rhonchi, which may indicate mucus or fluid buildup. Characterize the color, amount, and consistency of any discharge or sputum. Note the characteristics of the cough, if any.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Asthma. Grunting respirations may be apparent during a severe asthma exacerbation, usually triggered by an upper respiratory tract infection or an allergic response. As the attack progresses, dyspnea, audible wheezing, chest tightness, and coughing occur. Patients may have a silent chest if air movement is poor. Immediate bronchodilator therapy is needed.

♦ Heart failure. A late sign of left-sided heart failure, grunting respirations accompany increasing pulmonary edema. Associated features include a productive cough, crackles, jugular vein distention, and chest wall retractions. Cyanosis may also be evident, depending on the underlying congenital cardiac defect.

♦ Pneumonia. Life-threatening bacterial pneumonia is common after an upper respiratory tract infection or cold. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia commonly affects children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. It causes grunting respirations accompanied by high fever, tachypnea, a productive cough, anorexia, and lethargy. Auscultation reveals diminished breath sounds, scattered crackles, and sibilant rhonchi over the affected lung. As the disorder progresses, the patient may also develop severe dyspnea, substernal and subcostal retractions, nasal flaring, cyanosis, and increasing lethargy. Some infants display GI signs, such as vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal distention.

♦ Respiratory distress syndrome. The result of lung immaturity in a premature infant (less than 37 weeks’ gestation) usually of low birth weight, this syndrome initially causes audible expiratory grunting along with intercostal, subcostal, or substernal retractions; tachycardia; and tachypnea. Later, as respiratory distress tires the infant, apnea or irregular respirations replace the grunting. Severe respiratory distress is characterized by cyanosis, frothy sputum, dramatic nasal flaring, lethargy, bradycardia, and hypotension. Eventually, the infant becomes unresponsive. Auscultation reveals harsh, diminished breath sounds and crackles over the base of the lungs on deep inspiration. Oliguria and peripheral edema may also occur.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Closely monitor the patient’s condition. Keep emergency equipment nearby in case respiratory distress worsens. Prepare to administer oxygen using a nasal cannula or face mask. Continually monitor oxygen saturation levels and deliver the minimum amount of oxygen possible, to avoid causing retinopathy of prematurity from excessively high oxygen levels.

Begin inhalation therapy with a bronchodilator, and administer an I.V. antimicrobial if the patient has pneumonia (or, in some cases, status asthmaticus). Follow these measures with chest physical therapy as necessary.

Prepare the patient for chest X-rays. Because sedatives are contraindicated during respiratory distress, the restless child must be restrained during testing, as necessary. To prevent exposure to radiation, wear a lead apron and cover the child’s genital area with a lead shield. If a blood culture is ordered, be sure to record on the laboratory slip any current antibiotic use.

Remember to explain all procedures to the patient’s parents and to provide emotional support.

Respirations, shallow

Respirations are shallow when a diminished volume of air enters the lungs during inspiration. In an effort to obtain enough air, the patient with shallow respirations usually breathes at an accelerated rate. However, as he tires or as his muscles weaken, this compensatory increase in respirations diminishes, leading to inadequate gas exchange and such signs as dyspnea, cyanosis, confusion, agitation, loss of consciousness, and tachycardia.

Shallow respirations may develop suddenly or gradually and may last briefly or become chronic. They’re a key sign of respiratory distress and neurologic deterioration. Causes include inadequate central respiratory control

over breathing, neuromuscular disorders, increased resistance to airflow into the lungs, respiratory muscle fatigue or weakness, voluntary alterations in breathing, decreased activity from prolonged bed rest, and pain.

over breathing, neuromuscular disorders, increased resistance to airflow into the lungs, respiratory muscle fatigue or weakness, voluntary alterations in breathing, decreased activity from prolonged bed rest, and pain.

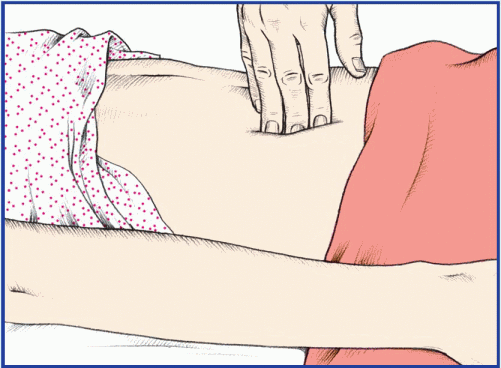

Positioning an infant for chest physical therapy

An infant with grunting respirations may need chest physical therapy to mobilize and drain excess lung secretions. Auscultate first to locate congested areas, and determine the best drainage position. Review the illustrations here, which show the various drainage positions and where to place your hands for percussion. When you percuss the infant, use the fingers of one hand. Vibrate these fingers and move them toward the infant’s head to facilitate drainage.

Hold the infant upright and about 30 degrees forward to percuss and drain the apical segments of the upper lobes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree