Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials

I am among those who think that science has great beauty. A scientist in his laboratory is not only a technician: he is also a child placed before natural phenomena which impress him like a fairy tale.

–Marie Curie (1867-1934).

We are here to add what we can to life, not to get what we can from life.

–Sir William Osler

Quality of life is used in this chapter to denote health-related quality of life. This has become a more commonly accepted measure of assessing efficacy in clinical trials in recent years, but most often as a secondary endpoint. Its use is spreading, and its importance is growing as a valid indicator of whether or not a medical treatment is beneficial. Quality of life may be viewed in terms of an individual, a group of patients, or a large population of patients. Each of these three categories of patients is discussed in this chapter, and primary attention is given to populations of patients.

One of the major reasons for confusion in this field is that different authors approach quality of life as well as pharmacoeconomic issues from totally different perspectives. While some of these differences may never be totally resolved, this chapter provides a frame of reference that may be used to approach both topics.

DEFINITION OF QUALITY OF LIFE

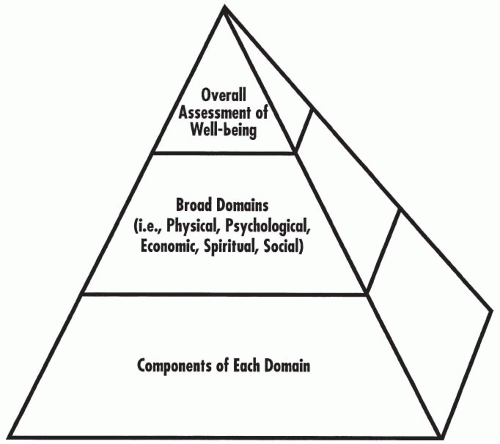

No single, clear, universally accepted definition of quality of life exists. Moreover, because the field is diverse and changing, it would be inappropriate to propose a single narrow definition. However, the definition of quality of life may be illustrated schematically as in Fig. 65.1. This figure shows that the definition of quality of life consists of three levels: (a) an overall level, (b) a level of about three to eight distinct domains, and (c) a level consisting of the individual components of each of the domains. Each of these levels is discussed in more detail in the section of this chapter titled “Quality of Life for Individual Patients and Groups of Patients.”

Many references now refer to health-related quality of life by another term, patient-reported outcomes (PROs). This latter term is more encompassing than simply quality of life, which is why this chapter is restricted to quality of life issues. PROs refer to all measures that are reported by a patient and capture the point that a critical outcome of a medical intervention is the state of health and well-being experienced by the patient. Therefore, PROs includes data reported by patients on health status, adherence to treatment (i.e., compliance), reports of symptoms, data from a diary, satisfaction with care received, assessment of clinical status, quality of life, and other characteristics. If a drug is being studied in a clinical trial, the outcomes may be viewed as PROs and may be measured in either efficacy or effectiveness trials.

Figure 65.1 Three levels of quality of life. In their totality, these three levels constitute the scope (and definition) of quality of life. |

Presents outcomes from the patient’s perspective and not the healthcare professional’s perspective

Extrapolates results more broadly than is done with randomized trials

May assess the usual care of patients in a “real-world” setting

Sometimes uses databases of patient-reported/assessed data as their data source

The term quality of life will be used in this chapter and throughout this book to refer to the somewhat more narrow definition of health-related quality of life than the broader one of PROs. The field of PROs is reviewed by Willke, Burke, and Erickson (2004); Wiklund (2004); and Leidy et al. (2006).

TYPES OF QUALITY OF LIFE

While it is widely agreed that health-related quality of life is not the only type of quality of life, there is no agreement on the number or identity of other specific types. The most often described other type is simply stated as non-health-related quality of life. Health-related quality of life uses the broad definition of health proposed by the World Health Organization: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” This broad definition, however, does not cover most non-health-type domains of quality of life.

Life events that happen to an individual are often independent of one’s health and have not been routinely assessed in clinical trials. Personal life events often affect health through stress, anxiety, or various emotions. Because of the intimate connection between social relationships and health (as defined by the World Health Organization) and also between spirituality and health, all quality-of-life domains should be assessed when health-related quality of life is measured. Therefore, descriptions of health-related quality-of-life domains include consideration of most personal issues, and they are usually discussed as a single entity. The relationship of life events and quality of life is discussed in Chapter 64.

Relative Importance of Two Types of Quality of Life

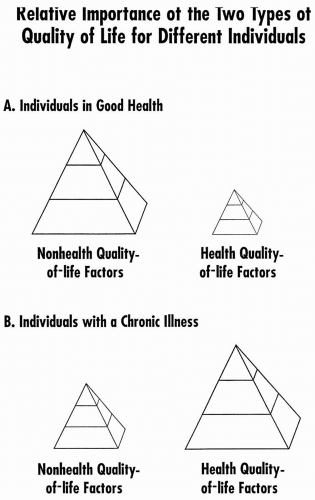

The relative importance of health-related and non-health-related quality of life on an individual basis varies depending on one’s state of health as well as on many other factors. Figure 65.2 illustrates this phenomenon by showing the importance of various domains and their components for healthy and chronically ill individuals.

DOMAINS OF QUALITY OF LIFE

The overall concept of quality of life consists of a number of distinct domains. The five major domains of quality of life generally referred to by most authors include the following categories:

Physical status and functional abilities

Psychological status and well-being

Social interactions

Economic and/or vocational status and factors

Religious and/or spiritual status

Some authors describe their research or clinical trials as dealing with quality-of-life issues when, in fact, they have studied only one or two of these broad domains. Clinical trials that evaluate only some domains should be distinguished from those that evaluate all domains because the former group cannot be said to have investigated the full range of quality-of-life characteristics. The most common counterargument to this proposal is that not all domains are pertinent to study in every study—and that is true. However, the pitfalls of not studying all domains (except perhaps spiritual) are described in Chapter 7 of Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials (Spilker 1996). The domains of quality of life do not differ for children as compared with adults, although some scales may be adapted specifically for children.

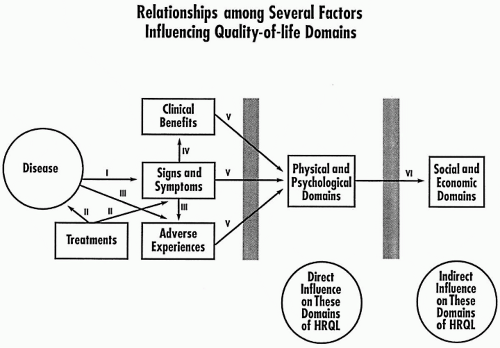

Figure 65.3 illustrates that a person’s disease and treatment affect one’s clinical signs, symptoms, adverse events, and clinical benefits in a complex way and need to be integrated by the individual in terms of how they are deemed to influence his or her physical and psychological domains of quality of life. These influences, in turn, then have an indirect effect on the social and economic domains.

To illustrate more clearly how events in the environment influence an individual’s quality of life, a few examples are listed below.

Water pollution may affect health, either acutely or chronically, in many ways.

The fear of crime may lead to psychological distress and physical manifestations, such as sweating, rapid heartbeat, and trembling.

Food that is tainted, covered with pesticide residues, or otherwise unfit for human consumption may cause mild, moderate, or even severe food poisoning.

A person who receives a letter of praise from someone in a distant place will generally feel good, and this may have a positive influence on one’s life, at least temporarily. This could be from a superior within the same organization or from someone unknown to the receiver of the letter that compliments or praises a publication or other professional accomplishment.

Spiritual Domain

The spiritual domain outcomes are primarily filtered through social and psychological processes and are generally distal to treatment outcomes. The spiritual domain is primarily important for comprehensively measuring quality of life but is not necessarily directly impacted by treatments. One reason for focusing on it in this chapter is that it is seldom considered in quality of life discussions.

The most direct approach to evaluate the spiritual domain is to interview a patient with a standard test or with a number of obvious questions:

How important is religion to you?

Are you a member of an organized religion?

How do you practice your religion?

How have your feelings about religion changed since you became ill?

How have your religious beliefs changed since you became ill and also since you began treatment?

Several theologians and religious scholars intimately concerned with quality of life from a spiritual perspective told the author that no validated instrument exists to address the previous questions. The author subsequently learned that the nursing literature contains various measures and Jan Ellerhorst-Ryan has written extensively on this subject.

The spiritual domain is mentioned because of the importance that it has in many people’s lives and the fact that it is rarely assessed

in clinical trials. There are many cases when its consideration would add value to a clinical trial. One only has to think of young Hispanics who do not volunteer for clinical trials because their concept of body image is based on religious beliefs. There are also clinical trials that ask or require people to do things that go against their religious beliefs, such as adhering to a special diet.

in clinical trials. There are many cases when its consideration would add value to a clinical trial. One only has to think of young Hispanics who do not volunteer for clinical trials because their concept of body image is based on religious beliefs. There are also clinical trials that ask or require people to do things that go against their religious beliefs, such as adhering to a special diet.

Figure 65.3 The relationships among several factors influencing quality-of-life domains. I: Disease causes or leads to a constellation of clinical signs and symptoms. II: Drugs and other treatments are directed at the underlying disease and/or ameliorating or eliminating signs and symptoms. In some cases, other treatments are directed to ameliorating adverse events. III:Treatments may elicit adverse events, as a result of attempts to affect either the underlying disease or the signs and symptoms resulting from the disease. IV: Treatments directed against clinical signs and symptoms may lead to clinical benefits. V: Signs and symptoms, benefits, and adverse events filter through the patient’s beliefs, judgments, and values to influence the physical and psychological domains. VI: Influences on the physical and/or psychological domain may, in turn, pass through the patient’s beliefs, judgments, and values to influence the social and economic domains. For example, a patient who feels better physically or psychologically may then be able to interact socially or to work at his or her job. HRQL, health-related quality of life. |

Every person has a spiritual domain, whether one considers oneself a believer, agnostic, or atheist. Given the central nature of spirituality to each person’s being, it is less likely to be altered by disease than the other domains and is less likely to be changed by therapy. However, there are a number of instances where changes in this domain would be expected:

A chronically ill patient may “lose his or her faith” or gradually alter his or her spiritual beliefs over a long period of time. Successful medical treatment could indirectly restore a person’s belief.

A sudden health crisis could lead to serious questioning of central spiritual beliefs.

A series of unexpected health problems among family or friends could lead to questioning, doubt, or rejection of certain beliefs—even if the patient was not directly affected himor herself.

The concept of spirituality for an individual usually differs from religion and the psychosocial dimension. Religion is often discussed by people using words such as systems, beliefs, organization, practices, and worship, whereas spirituality is often discussed using words such as life principle, being, quality, relationship, personal, and transcendent. The difference is usually one of viewing religion as

an organized external activity and spirituality as part of one’s self. Clearly, there is a large overlap for many people.

an organized external activity and spirituality as part of one’s self. Clearly, there is a large overlap for many people.

Which Domains Should Be Assessed in a Clinical Trial?

An important issue concerns deciding which domains of quality of life should be measured in a clinical trial and choosing the tests to be used to assess these domains. This is an important issue because it is often possible to measure just the specific domain(s) and components that are most likely (or even known) to show the changes desired. This is equivalent to “stacking the deck” before the game is played. This quasi-ethical approach of only choosing those domains or components to measure that one knows will turn out the way one wishes will be prevented when decision makers (e.g., on formulary committees, insurance companies) refuse to accept partial data and journals refuse to publish data obtained in such trials. This issue is of particular importance to regulators because they want sponsors to identify a priori those domains that will be most impacted by treatment and that are desired to have in the product label. If a sponsor desires a health-related quality-of-life label or promotional claim, then all of the domains in a comprehensive assessment will need to be measured and be either positively impacted by treatment or, apart from the major effects in one or more domains, show no impact.

Measures Used to Evaluate Quality of Life

Measures vary from standard validated questionnaires and evaluations using objective and/or subjective parameters to general questions prepared informally as an interview or questionnaire in a clinical trial. These latter nonvalidated tests or scales may be insensitive to changes brought about by drugs, and responses to the questions may not be reproducible. It is necessary to agree on the different attributes and relative importance of each test ahead of time. In some situations, using a single overall index relating to quality of life is highly desirable. Until the 1980s, the patient’s quality of life was generally assessed in clinical trials, if at all, through the filter of the physician.

Many existing quality-of-life scales may be applied to patients with any disease. In addition, numerous validated disease-specific scales are available. There are proponents of using general scales even when disease-specific scales are available. This is usually based on a greater degree of validation of the scale.

When it is uncertain as to which type(s) of tests to use in measuring quality of life in a specific clinical trial, it is usually appropriate to use a battery of tests that measures each of the major aspects of quality of life. This may be done using both standard assessments that are applicable to many diseases and also trial-specific measures designed for that particular disease. Caution must be used to choose tests that have been validated. There is a great temptation in this field for people to make up their own test and not to appreciate the importance of validating their test.

DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES ON HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE

Levels at Which Quality of Life Is Assessed

One may focus on differences and/or similarities among different countries, regions, and other geographical groups, down to the level of the individual and his home (Fig. 65.4). Quality-of-life issues have been widely explored among countries and have shown both amazing differences and similarities (Spilker 1996). In addition to considering progressively larger geographical units from a single home to the world, it is also possible to focus solely on patients in conceptualizing different levels of quality of life. Figure 65.5 illustrates five levels of patient groups varying from a single patient to all those who have a specific disease.

Type of Group Measuring or Assessing Quality of Life

From a health planner’s perspective, the quality-of-life issue is usually one of obtaining the greatest benefits with limited financial resources. The government, Health Maintenance Organization, or other planner wants to spend the limited money and resources available where they will achieve the greatest return on the group’s investment. The health planner has a predominantly economic perspective.

The perspective on this issue from a psychologist’s point of view is to maximize the social functioning of the individual patient. This includes the ability to work or to attend school.

Clinicians focus primarily on a patient’s medical health and physical abilities.

Patients focus primarily on how their disease and its treatment impact their everyday lives and interfere with what they want to do (i.e., function). If they are being treated to minimize a risk factor, then they will focus on the perceived benefits versus the inconvenience, cost, adverse events, and risk of the treatment.

Pharmaceutical companies want to obtain data to show benefits of their drugs over the competitors for marketing advantages and also to help get their drug listed on hospital, Health Maintenance Organization, and other formularies.

USES OF QUALITY-OF-LIFE DATA

One of the most important and basic questions about quality of life is: Why should it be studied, and what data support its use? The answer is most obvious for an individual patient: Quality-of-life trials can provide information that may help improve the quality of that patient’s treatment and outcomes. In addition, quality-of-life trials may be used to differentiate between two therapies with marginal differences in mortality or morbidity or to compare outcomes between two different treatment modalities, such as drug versus surgery. Quality-of-life data may show benefits of a drug where it does not improve clinical signs or symptoms of a disease per se but improves the patient’s ability to function with the disease. In addition, these data may be used to estimate the burden of specific diseases and to compare the impact of different diseases on functioning and well-being.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree