Hypoxemia has serious adverse consequences and must be treated aggressively to avoid pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure (cor pulmonale). When PaO2 falls below 60 mm Hg, significant desaturation of hemoglobin occurs and oxygen delivery to tissues is impaired.

The pulmonary vasculature responds to low oxygen tension by vasoconstriction. This highly conserved primitive response serves the useful function of diminishing blood flow through sections of the lung that are poorly ventilated but well perfused, the so-called V/Q mismatch. By limiting flow to the poorly ventilated (hypoxic) areas vasoconstriction reduces the impact of the V/Q mismatch on systemic PaO2.

Like every compensatory mechanism, however, there is a price to pay: in the presence of systemic hypoxemia pulmonary arterial vasoconstriction results in pulmonary hypertension and, eventually, right ventricular failure (cor pulmonale) since the right ventricle tolerates a pressure load poorly. The treatment is provision of supplemental oxygen to maintain the PaO2 above 60 mm Hg.

Tissue oxygenation is influenced by the oxygen/hemoglobin dissociation curve; when this curve is shifted to the left so that less oxygen is released at a given PaO2, hypoxia, a deficiency of oxygen at the tissue level, may result (see Fig. 2.2).

Tissue oxygenation is influenced by the oxygen/hemoglobin dissociation curve; when this curve is shifted to the left so that less oxygen is released at a given PaO2, hypoxia, a deficiency of oxygen at the tissue level, may result (see Fig. 2.2).

Factors that shift the dissociation curve to the right, favoring oxygen release and therefore tissue oxygenation, include red cell 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG) and systemic acidosis. These facts have implications for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis.

CO2 retention (hypercarbia or hypercapnia) is synonymous with alveolar hypoventilation.

CO2 retention (hypercarbia or hypercapnia) is synonymous with alveolar hypoventilation.

In the absence of significant neuromuscular disease or severe obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the usual cause. It results in respiratory acidosis and a compensatory rise in serum bicarbonate.

Prolonged and severe hypercapnia may be associated with a metabolic encephalopathy characterized by somnolence, asterixis, and papilledema, the latter reflective of cerebral vasodilation.

Prolonged and severe hypercapnia may be associated with a metabolic encephalopathy characterized by somnolence, asterixis, and papilledema, the latter reflective of cerebral vasodilation.

Treatment of hypoxemia in alveolar hypoventilation is essential, but supplemental oxygen must be administered judiciously (e.g., low flow oxygen at 2 L/min to achieve a PaO2 of 60 mm Hg) as oxygen may depress respirations further and result in respiratory arrest. Obviously, sedative medications are to be avoided.

Ondine’s curse, failure of the central respiratory center, particularly during sleep, also known as primary alveolar hypoventilation, causes hypercarbia, hypoxemia, and death from respiratory failure.

Ondine’s curse, failure of the central respiratory center, particularly during sleep, also known as primary alveolar hypoventilation, causes hypercarbia, hypoxemia, and death from respiratory failure.

Ondine was a nymph of German myth that delivered a curse to her unfaithful husband who had promised that “every waking breath” would bear testimony to his love. This is a disease of unknown cause that would result in death from respiratory failure but for a lifetime of mechanical ventilation.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an important cause of hypertension and daytime sleepiness.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an important cause of hypertension and daytime sleepiness.

Collapse of the upper airway causes stertorous breathing and gives way to apnea which may occur hundreds of times a night. The asphyxia that follows the apnea leads to repeated awakenings and disruption of normal sleep. In addition to sleepiness during the daytime, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity is increased substantially by OSA; this increase persists during the daytime and is an important cause of the hypertension that results from OSA since effective treatment diminishes both the sympathetic stimulation and the hypertension.

An important unheralded cause of both snoring and OSA is failure of the genioglossus muscle to open the airway by pulling the base of the tongue forward to the jaw.

An important unheralded cause of both snoring and OSA is failure of the genioglossus muscle to open the airway by pulling the base of the tongue forward to the jaw.

The genioglossus, which arises from the tip of the mandible and inserts on the base of the tongue, is the first respiratory muscle to contract during a respiratory cycle. Impaired function during sleep, particularly when lying supine, allows the base of the tongue to occlude the upper airway producing the sonorous noises called snoring. Most patients with OSA have a history of loud snoring but most individuals who snore do not have OSA. Alcohol, nighttime sedatives, and supine position accentuate the problem.

Most, but not all, patients with OSA are obese. This association is probably multifactorial, but fat deposits occluding the airway and infiltrating the genioglossus are likely involved.

Most, but not all, patients with OSA are obese. This association is probably multifactorial, but fat deposits occluding the airway and infiltrating the genioglossus are likely involved.

Interestingly, even small amounts of weight loss can produce significant improvement in OSA. Treatment is aimed at keeping the airway open by avoiding predisposing causes, and by the application of devices that deliver positive pressure to the upper airway. Mouth pieces that protrude the jaw forward and prevent the collapse of the base of the tongue have also been tried with some success. Electrical devices that stimulate the hypoglossal nerve and contract the genioglossus muscle are in clinical trials.

Hyperventilation Syndrome

Psychogenic hyperventilation is a prominent cause of dyspnea in healthy young adults; frequent sighing is a common manifestation and should suggest the diagnosis.

Psychogenic hyperventilation is a prominent cause of dyspnea in healthy young adults; frequent sighing is a common manifestation and should suggest the diagnosis.

Most common in anxious young healthy women, hyperventilation usually presents as dyspnea. Respiratory alkalosis is present and is frequently associated with latent tetany. Elicitation of a Chvostek sign is helpful in establishing the diagnosis. Perioral parasthesias are common as well.

The symptoms of hyperventilation can frequently be reproduced by having the patient voluntarily overbreathe.

The symptoms of hyperventilation can frequently be reproduced by having the patient voluntarily overbreathe.

Hypophosphatemia and a slight rise in calcium (alkalosis increases binding to albumin) are frequently present and may initiate an unwarranted investigation for hyperparathyroidism. Hyperventilation is also a well-recognized component of panic attacks.

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTS

Measurement of lung volumes and expiratory flow rate distinguishes between restrictive (interstitial) and obstructive lung disease.

Measurement of lung volumes and expiratory flow rate distinguishes between restrictive (interstitial) and obstructive lung disease.

Investigating a patient with dyspnea begins with a chest x-ray and pulmonary function tests (PFTs). Both obstructive and restrictive lung diseases cause reduced vital capacity. Patients with interstitial lung disease have reduced lung volumes while lung volumes are increased in patients with obstructive lung disease.

Measurement of diffusing capacity (DLCO) utilizes the affinity of hemoglobin for carbon monoxide (CO) to assess impairment of oxygen diffusion across the alveolar membrane.

Measurement of diffusing capacity (DLCO) utilizes the affinity of hemoglobin for carbon monoxide (CO) to assess impairment of oxygen diffusion across the alveolar membrane.

DLCO is reduced in most lung diseases including restrictive and obstructive disease. It is increased in pulmonary hemorrhage.

An elevated DLCO, especially if marked, in a patient with changing pulmonary infiltrates is diagnostic of pulmonary hemorrhage.

An elevated DLCO, especially if marked, in a patient with changing pulmonary infiltrates is diagnostic of pulmonary hemorrhage.

PNEUMONIA

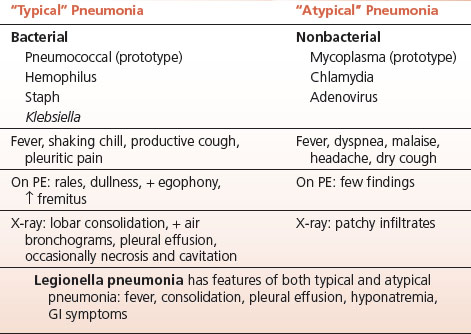

Classifying pneumonias as “typical” or “atypical” remains useful since it provides insight into the likely infectious organism and guides appropriate treatment (Table 10-1).

Classifying pneumonias as “typical” or “atypical” remains useful since it provides insight into the likely infectious organism and guides appropriate treatment (Table 10-1).

Although recognition of nosocomial infection as a cause of pneumonia is obviously important, the current widely embraced classification of pneumonia as “hospital acquired” or “community acquired” is not very helpful. It is self-evident that an institutionalized, or recently institutionalized, patient needs broad spectrum coverage for those organisms likely to be acquired in hospital or nursing home. The same is true for patients who are immunocompromised either from underlying disease or medications.

TABLE 10.1 Pneumonia

“Typical” Pneumonias

The term “typical” in the context of pneumonia implies a bacterial etiology. Lobar consolidation and pleuritic chest pain are characteristics.

The term “typical” in the context of pneumonia implies a bacterial etiology. Lobar consolidation and pleuritic chest pain are characteristics.

Pneumococcal pneumonia, caused by the pneumococcus (Streptococcus pneumoniae) is the prototype of the “typical” pneumonia.

Pneumococcal pneumonia, caused by the pneumococcus (Streptococcus pneumoniae) is the prototype of the “typical” pneumonia.

It classically begins with a single shaking chill, cough, pleuritic chest pain, and a steady high fever (not spiking, absent antipyretics). The sputum is typically blood tinged or “rusty.” Physical examination reveals signs of consolidation: dullness, increased fremitus, rales, and bronchial breath sounds over the affected area. On chest x-ray lobar consolidation with air bronchograms is the usual finding. A reactive pleural effusion may be present; if so, empyema must be ruled out. Examination of the sputum reveals many polys with intracellular diplococci. Blood cultures may be positive. Strangely, sputum culture fails to grow pneumococci in up to half the cases, for reasons that remain obscure.

Metastatic infection, although an uncommon complication of pneumococcal pneumonia, is severe and may be life threatening; these sites include the meninges, the aortic valve, and the joints.

Metastatic infection, although an uncommon complication of pneumococcal pneumonia, is severe and may be life threatening; these sites include the meninges, the aortic valve, and the joints.

There is a peculiar predilection for pneumococci to infect the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints.

There is a peculiar predilection for pneumococci to infect the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints.

Shoulder pain in a patient with pneumococcal pneumonia or pneumococcal meningitis should prompt evaluation of these joints.

Some pneumococcal serotypes produce necrotizing lesions in the lung with prominent hemoptysis.

Some pneumococcal serotypes produce necrotizing lesions in the lung with prominent hemoptysis.

The pathogenesis of pneumococcal pneumonia requires invasion of the lower respiratory tree.

The pathogenesis of pneumococcal pneumonia requires invasion of the lower respiratory tree.

Since substantial numbers of normal people harbor pneumococci in the nasopharynx without getting sick, particularly in the winter months in temperate climes, a predisposing factor usually can be identified. Pulmonary defense mechanisms are usually adequate to block access to the lower tract; invasion of the alveolar spaces and pneumonia develop when those defense mechanisms are compromised.

The usual cause of predisposing altered pulmonary defense is a prior viral upper respiratory infection, but other factors that lead to the development of pneumonia include smoking, alcohol intake, stupor, or coma.

The usual cause of predisposing altered pulmonary defense is a prior viral upper respiratory infection, but other factors that lead to the development of pneumonia include smoking, alcohol intake, stupor, or coma.

Response of pneumococcal pneumonia to penicillin is usually prompt (within a few days). A secondary fever spike may occur as the patient improves 2 to 3 days after the fever breaks; this may reflect cleaning up of the consolidation by the host defenses.

Haemophilus influenzae is another cause of typical pneumonia. The sputum may be “apple green” rather than rusty.

Haemophilus influenzae is another cause of typical pneumonia. The sputum may be “apple green” rather than rusty.

Staphylococcal pneumonia is a significant cause of postinfluenza morbidity.

Staphylococcal pneumonia is a significant cause of postinfluenza morbidity.

A patchy bronchopneumonia with a tendency to cause necrosis and cavitation staph pneumonia requires prompt antibiotic treatment.

Klebsiella pneumonia is a severe gram-negative infection most commonly nosocomial and usually affecting patients with impaired host defense mechanisms such as alcoholism and diabetes. X-ray shows patchy broncopneumonic consolidation frequently with pleural effusions.

Klebsiella pneumonia is a severe gram-negative infection most commonly nosocomial and usually affecting patients with impaired host defense mechanisms such as alcoholism and diabetes. X-ray shows patchy broncopneumonic consolidation frequently with pleural effusions.

Legionella pneumonia, although bacterial, has many atypical features and should be considered particularly if hyponatremia is prominent and GI symptoms and headache are present (Table 10-1).

Legionella pneumonia, although bacterial, has many atypical features and should be considered particularly if hyponatremia is prominent and GI symptoms and headache are present (Table 10-1).

Diagnosis of legionella is by urinary antigen or, less useful, direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing. Both are specific but lack sensitivity.

Influenza

Influenza, because of its aggressive attack on the tracheal and bronchial mucosa, is the prototypic predisposition to bacterial pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia is frequently the cause of death in influenza epidemics.

Influenza, because of its aggressive attack on the tracheal and bronchial mucosa, is the prototypic predisposition to bacterial pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia is frequently the cause of death in influenza epidemics.

Although pneumococci are the most frequent cause of pneumonia post influenza, the incidence of staphylococcal pneumonia post influenza is significantly increased.

Although pneumococci are the most frequent cause of pneumonia post influenza, the incidence of staphylococcal pneumonia post influenza is significantly increased.

The latter is a serious infection and delay in treatment of as little as 12 hours may mean the difference between uneventful recovery and extensive lung involvement with necrosis and respiratory failure. Staph pneumonia is usually a patchy bronchopneumonia rather than a dense lobar consolidation.

Influenza pneumonia, caused by the virus itself rather than bacterial superinfection, is a serious interstitial pneumonitis that may cause severe hypoxemia and death.

Influenza pneumonia, caused by the virus itself rather than bacterial superinfection, is a serious interstitial pneumonitis that may cause severe hypoxemia and death.

The infiltrate may be widespread and cough is productive of a watery serosanguinous, rather than a purulent, sputum.

Shaking chills and muscle aches are common in influenza and may result in rhabdomyolysis if severe.

Shaking chills and muscle aches are common in influenza and may result in rhabdomyolysis if severe.

CPK may be elevated in severe influenza.

Atypical Pneumonia

Mycoplasma pneumonia is the prototype of the atypical pneumonias; additional etiologic agents include chlamydia, adenovirus, and other respiratory viruses. These infections usually have nonproductive cough, an x-ray picture of patchy nonsegmental infiltrates out of proportion to the clinical examination, which usually reveals a paucity of findings.

Pleuritis and pleural effusions are absent in atypical pneumonias. Shortness of breath, fatigue, and particularly headache are commonly associated.

Pleuritis and pleural effusions are absent in atypical pneumonias. Shortness of breath, fatigue, and particularly headache are commonly associated.

Eosinophilia and Pulmonary Infiltrates

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is a relapsing acute pneumonitis affecting middle-aged women predominately, and characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the peripheral portions of the lungs.

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is a relapsing acute pneumonitis affecting middle-aged women predominately, and characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the peripheral portions of the lungs.

CBC frequently shows eosinophilia and a past history of asthma is common. Steroid treatment is usually beneficial at inducing remission.

Eosinophilia in association with pulmonary infiltrates also suggests a drug reaction or Churg–Strauss vasculitis.

Eosinophilia in association with pulmonary infiltrates also suggests a drug reaction or Churg–Strauss vasculitis.

SARCOIDOSIS

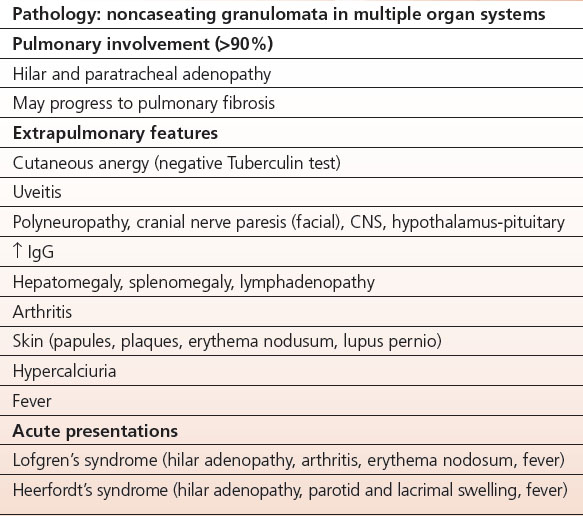

An immunologic response to as yet unidentified antigens, sarcoidosis is a generalized disease with most prominent involvement in the lung (Table 10-2).

Pulmonary Involvement in Sarcoidosis

Lung involvement is present in over 90% of patients with sarcoidosis.

Lung involvement is present in over 90% of patients with sarcoidosis.

The characteristic pathologic findings are scads of noncaseating granulomata with multinucleate giant cells, which are commonly seen on transbronchial biopsy and therefore very useful in establishing the diagnosis.

The chest x-ray findings in sarcoid include, most prominently, bilateral hilar adenopathy, paratracheal adenopathy, and varying degrees of pulmonary fibrosis depending on the stage.

The chest x-ray findings in sarcoid include, most prominently, bilateral hilar adenopathy, paratracheal adenopathy, and varying degrees of pulmonary fibrosis depending on the stage.

In advanced stage pulmonary disease, hilar adenopathy disappears and fibrosis dominates the clinical picture. In the United States sarcoidosis is most common in African Americans, particularly women.

Extrapulmonary Manifestations of Sarcoidosis

Multisystem involvement in sarcoidosis is common.

Multisystem involvement in sarcoidosis is common.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis are legion and may include the eye, the pituitary and hypothalamus, peripheral nerves, skin, joints, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, parotid gland, hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, fever, hypergammaglobulinemia, and cutaneous anergy. The related clinical features may include uveitis, diabetes insipidus, endocrine abnormalities, polyneuritis, and cranial nerve palsies (principally the VII – Bell’s palsy), splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy. Hepatic involvement with granulomas is common but usually subclinical, although the alkaline phosphatase may be elevated.

TABLE 10.2 Sarcoidosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree