KEY TERMS

One expectation about living in a civilized society is that the living conditions will be basically healthy. Unless something unusual happens, like the outbreak of Cryptosporidium in the Milwaukee water supply, people assume that they are basically safe: Their water is safe to drink; the hamburger they buy at the fast food restaurant is safe to eat; the aspirin they take for a headache is what the label says it is; and they are not likely to be hit by a car—or a bullet—if they use reasonable caution in walking down the street. Even after the attacks in the fall of 2001, which severely disrupted their sense of security, most Americans regained a sense of trust in the safety of their environment.

In historical terms, this expectation is a relatively recent development. In the mid-19th century, when record-keeping began in England and Wales, death rates were very high, especially among children. Of every ten newborn infants, two or three never reached their first birthday. Five or six died before they were six years old, and only about three of the ten lived beyond the age of 25.1 Tuberculosis was the single largest cause of death in the mid-19th century. Epidemics of cholera, typhoid, and smallpox swept through communities, killing people of all ages and making them afraid to leave their homes. Injuries—often fatal—to workers in mines and factories were common due to unsafe equipment, long working hours, poor lighting and ventilation, and child labor.

There are a number of reasons why people’s lives are basically healthier today than they were 150 years ago: cleaner water, air, and food; safe disposal of sewage; better nutrition; more knowledge concerning healthy and unhealthy behaviors; and many others. Most of these factors fall in the domain of public health. In fact, the term “public health” refers to two different but related concepts. We can say that the public health has improved since the 19th century, meaning that the general state of people’s health is now much better than it was. But the measures that people take as a society to bring about and maintain that improvement are also known as public health.

Although many sectors of the community may be involved in promoting public health, people most often look to government—at the local, state, or national level—to take the primary responsibility. Governments provide pure water and efficient sewage disposal. Governmental regulations ensure the safety of the food supply. They also ensure the quality of medical services provided through hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions. Laws regulating people’s behavior prevent them from injuring each other. Laws requiring immunization of school-aged children prevent the spread of infectious diseases. Governments also sponsor research and education programs on causes and prevention of disease.

What Is Public Health?

Public health is not easy to define or to comprehend. A telephone survey of registered voters conducted in 1999 by a charitable foundation found that over half of the 1234 respondents misunderstood the term.2 Leaders in the field have themselves struggled to understand the mission of public health, to explain what it is, why it is important, and what it should do. Charles-Edward A. Winslow, a theoretician and leader of American public health during the first half of the 20th century, defined public health in 1920 this way:

The science and the art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical health and efficiency through organized community efforts for the sanitation of the environment, the control of community infections, the education of the individual in principles of personal hygiene, the organization of medical and nursing services for the early diagnosis and preventive treatment of disease, and the development of the social machinery which will ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health.3(p.1)

Winslow’s definition is still considered valid today.

Over the following decades, public health had many successes, carrying out many of the tasks described in Winslow’s definition. It was highly effective in reducing the threat of infectious diseases, thereby increasing the average lifespan of Americans by several decades. By the 1980s, public health was taken for granted, and most people were unaware of its activities. But there were signs that the system was not functioning well. Government expenditures on health were alarmingly high, but most of the spending was directed toward medical care. No one was talking about public health. At the same time, new health problems were appearing: The AIDS epidemic broke out, concern about environmental pollution was growing, the aging population was demanding increased health services, and social problems such as teenage pregnancy, violence, and substance abuse were becoming more common. There was a sense that public health was not prepared to deal with these problems, in part because people were not thinking of them as public health problems.

A study conducted by the Institute of Medicine and published in 1988 called The Future of Public Health refocused attention on the importance of public health and did a great deal to revitalize the field. One of the first tasks the study committee set for itself was to re-examine the definition of public health, reasoning that for it to be effective, public health had to be broadly defined.4 The committee’s report gives a four-part definition describing public health’s mission, substance, organizational framework, and core functions.

The Future of Public Health defines the mission of public health as “the fulfillment of society’s interest in assuring the conditions in which people can be healthy.”4(p.40) The substance of public health is “organized community efforts aimed at the prevention of disease and the promotion of health.”4(p.41) The organizational framework of public health encompasses “both activities undertaken within the formal structure of government and the associated efforts of private and voluntary organizations and individuals.”4(p.42) The three core functions of public health are these:

1. Assessment

2. Policy development

3. Assurance4(p.43)

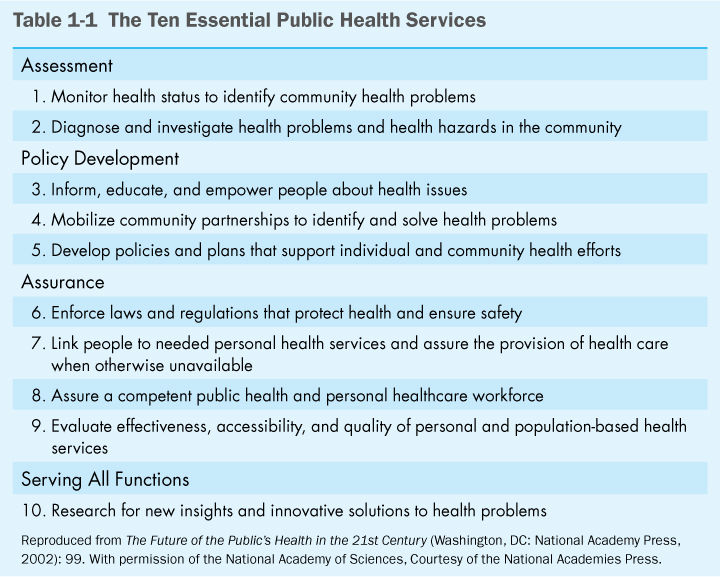

These core functions were later translated by another committee into a more concrete set of activities called The Ten Essential Public Health Services, shown in (Table 1-1).

Public Health Versus Medical Care

One way to better understand public health and its functions is to compare and contrast it with medical practice. While medicine is concerned with individual patients, public health regards the community as its patient, trying to improve the health of the population. Medicine focuses on healing patients who are ill. Public health focuses on preventing illness.

In carrying out its core functions, public health—like a doctor with his/her patient—assesses the health of a population, diagnoses its problems, seeks the causes of those problems, and devises strategies to cure them. Assessment constitutes the diagnostic function, in which a public health agency collects, assembles, analyzes, and makes available information on the health of the population. Policy development, like a doctor’s development of a treatment plan for a sick patient, involves the use of scientific knowledge to develop a strategic approach to improving the community’s health. Assurance is equivalent to the doctor’s actual treatment of the patient. Public health has the responsibility of assuring that the services needed for the protection of public health in the community are available and accessible to everyone. These include environmental, educational, and basic medical services. If public health agencies do not provide these services themselves, they must encourage others to do so or require such actions through regulation.

Public health’s focus on prevention makes it more abstract than medicine, and its achievements are therefore more difficult to recognize. The doctor who cures a sick person has achieved a real, recognizable benefit, and the patient is grateful. Public health cannot point to the people who have been spared illness by its efforts. As Winslow wrote in 1923, “If we had but the gift of second sight to transmute abstract figures into flesh and blood, so that as we walk along the street we could say ‘That man would be dead of typhoid fever,’ ‘That woman would have succumbed to tuberculosis,’ ‘That rosy infant would be in its coffin,’—then only should we have a faint conception of the meaning of the silent victories of public health.”3(p.65)

This “silence” accounts in large part for the relative lack of attention paid to public health by politicians and the general public in comparison with medical care. It is estimated that only about 3 percent of the nation’s total health spending is spent on public health.5 During the healthcare reform debate of 1993 and 1994, and again in 2008 during the presidential campaign, virtually all of the discussion focused on paying for medical care, while very little attention was paid to funding for public health. However, President Obama’s health reform law, passed in 2010, did include provisions and funding for prevention, wellness, and public health.6

Effective public health programs clearly save money on medical costs in addition to saving lives. Moreover, public health contributes a great deal more to the health of a population than medicine does. According to one analysis, the life expectancy of Americans has increased from 45 to 75 years over the course of the 20th century.7 Only 5 of those 30 additional years can be attributed to the work of the medical care system. The majority of the gain has come from improvements in public health, broadly defined as including better nutrition, housing, sanitation, and occupational safety. One responsibility of public health, therefore, as noted in the Institute of Medicine report, is to educate the public and politicians about “the crucial role that a strong public health capacity must play in maintaining and improving the health of the public … By its very nature, public health requires support by members of the public—its beneficiaries.”4(p.32)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree