KEY TERMS

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Throughout evolutionary history, humans had to exert a great deal of physical activity to obtain their food. Only over the past century has a substantial and increasing percentage of the population had access to an excess of food with no need to exercise. The consequence of this imbalance has been that Americans are becoming fatter, an exceedingly unhealthy trend. Today, poor diet and physical inactivity have been ranked second among the factors identified as leading actual causes of death in the United States, although the analysis is controversial.

Many studies have shown that weighing too much increases people’s risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, most kinds of cancer, and a variety of other diseases. Thus, it is in the interest of public health to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity, which in 2009–2012 affected 68.7 percent of the adult population.1(Table 64) Getting people to lose weight, however, seems to be even more difficult than getting them to quit smoking, although many of them want to be thinner. According to the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 57 percent of women and 37 percent of men are trying to lose weight, most of them unsuccessfully.2 An Institute of Medicine report on the problem states, “It is paradoxical that obesity is increasing in the United States while more people are dieting than ever before, spending, by one estimate, more than $33 billion per year on weight-reduction products (including diet foods and soft drinks, artificial sweeteners, and diet books) and services (e.g., fitness clubs and weight-loss programs).”3(p.27)

The association of obesity with certain health risks is easy to measure, but the relationship may not be a simple one of cause and effect. Obesity is a complex condition, influenced by genes as well as by many individual and social factors that include eating and exercise patterns. While being overweight has a health impact in itself, a person’s disease risk may also be affected independently by dietary patterns and the amount of physical activity, whether or not he or she is overweight. Public health advocates, therefore, seek to promote healthier eating patterns among Americans, to encourage them to exercise more, and to reduce the percentage of people who are overweight.

Epidemiology of Obesity

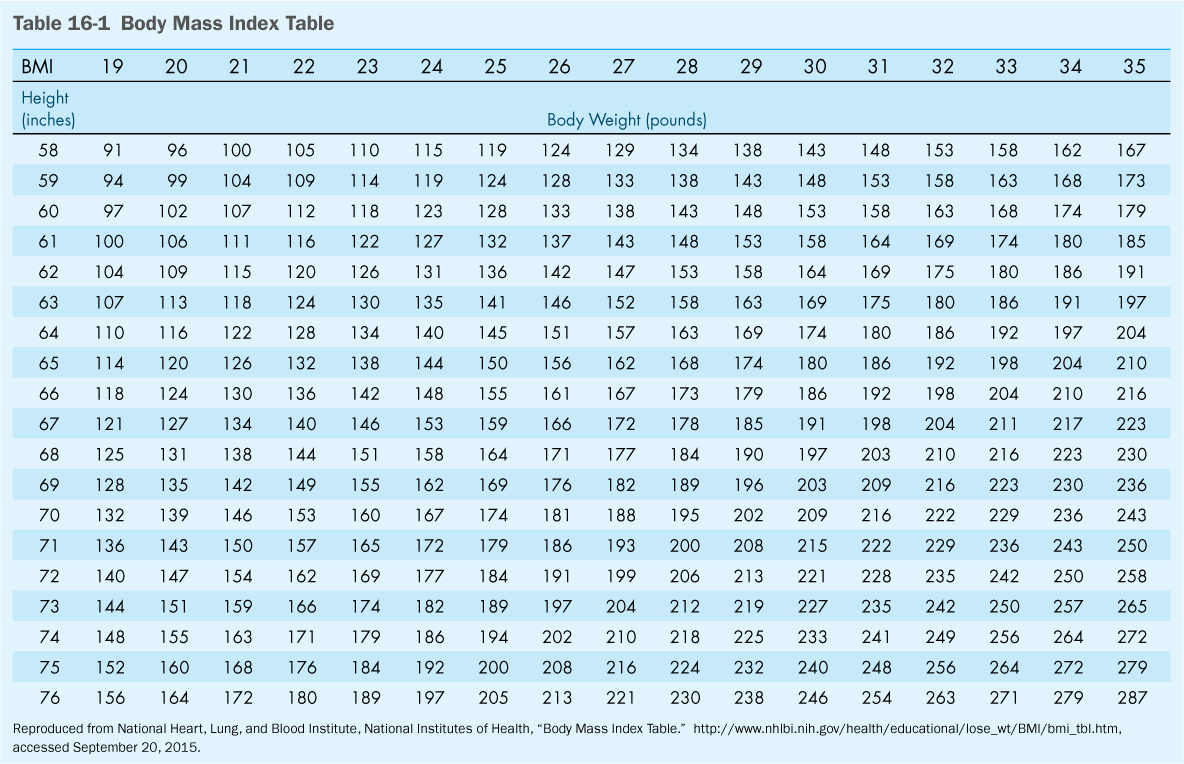

Obesity is, to an extent, in the eyes of the beholder—often the beholder who is looking in the mirror. In the public health perspective, obesity is usually defined more precisely in terms of body-mass index (BMI). BMI is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms by the square of his or her height in meters. (Table 16-1) presents BMIs in terms of inches and pounds for a range that includes most Americans.

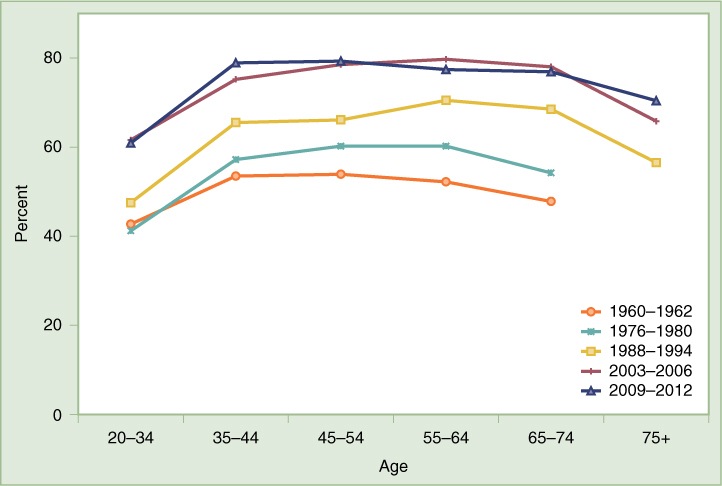

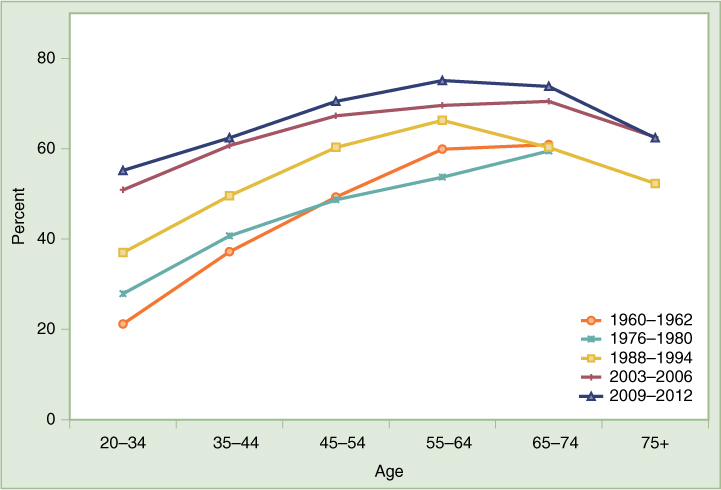

Most studies show that weight-associated health risks begin to appear at a BMI of about 25, and rise more significantly above 30, with the risks increasing in proportion to the severity of an individual’s obesity. The National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have agreed on a definition of overweight as a BMI between 25 and 29.9 and obesity as a BMI of 30 or greater.4 Using this definition, 72.9 percent of men and 64.6 percent of women 20 years of age and older were found to be overweight or obese in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted between 2009 and 2012.1 The prevalence of obesity was 34.6 percent in men and 35.9 percent in women. The prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased dramatically over the past decades, as shown in (FIGURES 16-1) and (16-2).

There are significant racial differences in the prevalence of overweight among women: 81.8 percent of nonpregnant black women are overweight, compared with 60.9 percent of white women. Among men the differences are smaller: 70.2 percent of black men compared with 73.2 percent of white men are overweight.1 The health effects of overweight and obesity are less marked among blacks. The optimal BMI has been calculated to be 23 to 25 for whites, while it is 23 to 30 for blacks.5 The risks of excess weight are known to be higher for Asian populations; so the BMI cutoffs recommended by the World Health Organization are lower for them.6 Due to insufficient data, it has not been possible to calculate ideal weights in other ethnic groups, including Mexican Americans, in whom the prevalence of overweight and obesity is 81.9 among men and 78.3 in women. Overweight increases with age, as seen in Figures 16-1 and 16-2, but declines in the age group 75 years and older.

Socioeconomic status has a significant influence on the prevalence of obesity. College graduates of both sexes are thinner than men and women with fewer years of education. The difference is especially significant among females: Those with less than 12 years of education are nearly twice as likely to be overweight than female college graduates. Among men, the relationship of obesity with education is less clear.7

The greater prevalence of obesity in black women compared to white women doubtless contributes to poorer health among blacks. Rates of cardiovascular disease and diabetes are higher in blacks than in whites, and an unhealthy diet is likely to be part of the problem. Many Hispanics and American Indians are also overweight, accounting for high rates of diabetes among these groups.

FIGURE 16-1 Percentage of Overweight Males, United States

Data from Health, United States, 2014, Table 69. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus14.pdf, accessed September 20, 2015.

FIGURE 16-2 Percentage of Overweight Females, United States

Data from Health, United States, 2014, Table 69. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus14.pdf, accessed September 20, 2015.

While being fat is bad for people’s health, the distribution of fat on the body makes a difference. Obesity researchers distinguish between apple-shaped people and pear-shaped people, and they have found health risks to be greater for those shaped like apples. People who gain weight in the abdominal area, as men usually do, have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes than people who gain weight in the hips and buttocks—a pattern more common in females. Fat distribution is measured as a waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), with the waist measured at the smallest point and the hips at the widest point around the buttocks. Health risks in men who have a WHR more than 1.0 and women whose WHR is more than 0.8 are greater than the risks due to excess weight alone.3

In an alarming trend, overweight among children has been increasing steadily since the 1960s. Definitions of overweight and obesity in children are complex calculations, based on growth curves of BMI for age. The CDC identifies children as overweight if they are at or above the 85th percentile on growth curves established before 1980 and as obese if they are above the 95th percentile.8,9 The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents 6 to 19 years old increased from under 5 percent in the earliest surveys to more than 34 percent in the 2011–2012 NHANES. Overweight and obesity is more prevalent in some ethnic groups: Black and Hispanic teenage boys and girls are heavier than their white counterparts; Asian girls are especially unlikely to have a high BMI.9

Children who are fat are likely to become fat adults and suffer the concomitant risks of chronic disease. For example, a study that tracked 679 school children for 16 years found that weight during childhood was a good predictor of whether an adult would exhibit risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes.10 Obese children are for the first time being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, which is sometimes called “adult-onset diabetes” because until recently it was believed to occur almost exclusively in adults.11 This is especially likely to occur in American Indian adolescents, who have a high prevalence of obesity, but blacks and Hispanics are also affected. Complications of childhood obesity involve virtually every organ, including the cardiovascular system, the respiratory system, the kidneys, the gastrointestinal system, and the musculoskeletal system.12 Evidence suggests that the harmful effects of excess weight increase with longer duration of obesity, implying that obese children are especially likely to suffer excess morbidity and mortality when they grow up.5 One study found that the obese adolescent girls are two or three times as likely to die by middle age as girls of normal weight.12

Obesity in children also tends to cause psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, social isolation, and low self-esteem. Children who are worried about their weight may undertake diets that affect their physical as well as their psychological health, and they are at increased risk for eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia. Obese children are less likely than thinner ones to complete college and are more likely to live in poverty.12

Diet and Nutrition

Obesity is caused by unhealthy eating patterns combined with inadequate physical activity, each a factor that influences people’s health whether or not they weigh too much. The public health aspects of physical activity will be discussed later in this chapter. This section and the next explore the role of diet in the prevention of chronic diseases, including obesity, and describe public health efforts to encourage people to eat a healthier diet.

Most analyses find that Americans eat too much protein and fat and too few fruits and vegetables. This pattern contributes to high levels of cholesterol and other blood lipids and to high blood pressure—risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The evidence is less clear on how the American diet increases cancer risk, but epidemiologic studies show that breast and colon cancer risks are greater in populations that eat diets high in meat and low in fruits and vegetables. Diet is a major factor in type 2 diabetes, which is often brought on by obesity and which can usually be controlled by careful eating. Osteoporosis, a debilitating disease of the elderly, especially white women, is likely to become increasingly common because young women are not getting enough calcium, best obtained in low-fat dairy products.

The federal government, in a number of reports over the years by various advisory committees, has developed recommendations on how Americans should eat to maintain health and prevent chronic disease. Since 1980, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have reviewed the recommendations every five years and have released reports called Dietary Guidelines for Americans.13 Agreeing on recommendations has often proved controversial, because the food industry tends to oppose any recommendation that calls for eating less of any food substance.14 However, evidence clearly supports the recommendations included in the 2010 guidelines that people’s diets should emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products; they should include lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, eggs, and nuts but less saturated fats, transfats, cholesterol, salt, and added sugar.15

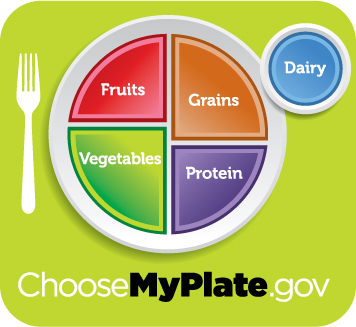

While the 2010 food guidelines did not change significantly from those issued earlier, the image used to illustrate the recommendations changed from the familiar food guide pyramid to a place setting for a meal, shown in (FIGURE 16-3). ChooseMyPlate.gov recommends, for example, that half the plate should consist of fruits and vegetables, and at least half the grains should be whole grains. The website includes an option for an individual to create a personal profile with a calorie limit, affected by his or her physical activity, and a recommended food plan.16

Work on the 2015 guidelines started in 2013, when an advisory committee was appointed. A series of meetings were held in 2014, and the final guidelines were scheduled to be published at the end of 2015.13

Dietary surveys conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture have shown that while the diet of Americans has improved over the past several decades, people fall far short of the federal recommendations. One-third of the population eats at least some food from all food groups, but only 1 percent to 3 percent eat the recommended number of servings from all food groups on a given day. Fruits are the most commonly omitted item. Intake of fat and added sugars continues to be too high. While people appear to eat close to the recommended number of vegetable servings, half of these servings are iceberg lettuce, potatoes (including chips and fries), and canned tomatoes.14,15 One unfortunate trend is that African Americans of low socioeconomic status, who used to eat a more healthful diet than wealthy whites, have now adopted eating patterns that have traditionally been associated with higher incomes. It is as if, as one commentator suggests, they feel they are now “able to afford steak instead of having to ‘fill up’ on bread or peas or beans.”17(p.739)

FIGURE 16-3 ChooseMyPlate.gov

Reproduced from United States Department of Agriculture, http://www.choosemyplate.gov, accessed September 16, 2015.

Federal surveys suggest that, among the causes of increasing obesity, especially in children, is the increased intake of sweetened beverages. The proportion of calories that the average American obtained from soft drinks and fruit drinks more than doubled between 1977 and 2001 and remains high.18,19 The trend was similar for all age groups, but the numbers were highest in the younger age groups, rising from 4.8 percent to 10.3 percent of calories in the 2- to 18-year-old group and from 5.1 percent to 12.3 percent among those between the ages of 19 and 39. Meanwhile, consumption of milk decreased by 38 percent overall, including among children age 2 to 18, the group for whom milk consumption is most important for future health. Consumption of other beverages has not changed significantly over the period studied. These trends are unhealthy, not only because soft drinks and sweetened juice drinks contain “empty calories” that contribute to weight gain, but also because consuming milk products appears to help people control their weight in addition to providing calcium for their bones. According to the researchers, reducing soft drink and fruit drink intake “would seem to be one of the simpler ways to reduce obesity in the United States.”18(p.209)

Promoting Healthy Eating

It might seem that what each individual eats is under his or her individual control. But many social, cultural, and economic factors contribute to dietary patterns. Eating habits and dietary preferences develop over a lifetime, influenced by family, ethnicity, the media, and other factors in the social environment. The high prevalence of overweight in the United States combined with the large numbers of people who are trying unsuccessfully to lose weight makes it clear that changing eating patterns is very difficult, even for highly motivated people. Studies of patients with a variety of medical conditions requiring special diets have found that even they have difficulty sticking to the prescribed diet. The rate of adherence to a diet by people with diabetes ranged from 20 percent to 53 percent to 73 percent in three different studies. People with kidney failure who were on dialysis were found to have a rate of adherence to the recommended diet of 39 percent and 42 percent in two separate studies. Another study found that the ability of people with high cholesterol to adhere to a low-cholesterol diet was only 30 percent.20

Several major public health campaigns conducted in entire communities and aimed at reducing cardiovascular risks found that obesity was the most difficult risk factor to control. The Stanford Three-Community Study, the Stanford Five-City Study, the Minnesota Heart Health Program, and the North Karelia (Finland) Project all had reasonable success in reducing risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and blood cholesterol, but none of them interrupted the increase in the prevalence of obesity in the communities studied.3

Nevertheless, public health advocates have attempted to apply the ecological model of health behavior to create a social environment that favors healthier eating. For example, making nutritious foods more readily available—intervention at the community and institutional levels—should encourage people to choose their foods more wisely. The food industry is responding to many consumers’ concerns about weight and health by providing a greater choice of low-fat and low-calorie foods. Many restaurants offer “heart healthy” selections on the menu and label them thus. Worksite and school cafeterias provide healthy food choices including salad bars. While such measures do not guarantee that people will eat a healthier diet, they remove barriers that make it hard for people to do so.

Enhancing self-efficacy and providing social support are ways of promoting healthy eating at the level of the individual and his or her family and friends.20 Social support is provided when a whole family is willing to adopt a diet together, or by group programs such as Weight Watchers. Self-efficacy can be improved by “point of choice” postings of nutritional information, which can help shoppers who are concerned about the nutritional content of food but do not know how to make wise choices. Several major campaigns using point of choice postings have been conducted by supermarket chains in collaboration with health advocacy organizations such as the American Heart Association, but the results have been mixed. Other approaches to enhancing self-efficacy and adherence to diets include demonstrations of healthy cooking methods and practice in calculating portion sizes.

Public health advocates look at evidence from antismoking campaigns for ideas on how to improve the social environment to affect the American diet. The success of the public service announcements of the 1960s, together with later bans on cigarette advertising in the broadcast media, in reducing smoking prevalence inspired a number of media campaigns to promote more healthful eating. One such campaign was California’s “5-A-Day” Campaign for Better Health, which attempted to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among state residents to five servings per day.14 The assumption is that eating more fruits and vegetables leads to eating less of nonnutritious foods. The program proved to be successful in increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables in the state. Later, the National Cancer Institute launched the program nationwide, although funding was never adequate to maintain the early successes of the California program. As in the case of antismoking campaigns, public health advocates must compete with well-financed advertising campaigns by food manufacturers promoting highly attractive but nonnutritious foods.

Another problem with the “5-A-Day” approach is that fresh fruits and vegetables are relatively expensive and are often unavailable in poor neighborhoods. Fast-food restaurants, on the other hand, are inexpensive and are often concentrated in low-income neighborhoods. Moreover, U.S. government policy subsidizes industrial agriculture, which produces high-calorie commodities at the expense of more nutritious produce.21 Food advertising focuses predominately on processed foods, which are more profitable for the industry.3

The food and beverage industries use some of the same approaches to increasing their sales as the tobacco companies have used. As documented in Marion Nestle’s book, Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health14 companies do everything they can to encourage Americans to eat more. They do this by processing foods to make them taste good, which often means sweet, fatty, or salty. They push larger portions, often by promoting them as good buys; for example, a large serving of fries might cost only pennies more than a small serving while it might have twice as many calories. The companies also advertise extensively, especially to children. They take advantage of the fact that, with most women working outside the home, convenience and efficiency are major factors in food choice and fewer family meals than in the past are home cooked. As Nestle describes, food companies “conduct systematic, pervasive, and unrelenting … campaigns to convince government officials, health organizations, and nutrition professionals that their products are healthful or harmless, to undermine any suggestion to the contrary, and to ensure that federal dietary guidelines and food guides will help promote sales.”14(p.26) Like tobacco companies, food companies argue that diet is a matter of individual choice, and they use science to sow confusion about the harm their products can do.

The Institute of Medicine, after a thorough study aimed at developing criteria for evaluating the outcomes of programs to prevent and treat obesity, concluded in a report called Weighing the Options that prospects were dim for people seeking to lose weight. “The fact is that despite the billions of dollars spent, few people reduce their body weight to a desirable or healthy level and even fewer maintain the weight lost beyond two or three years.”3(p.158) The report noted that for most people, weight is not lost once and for all but that its control demands continuing effort. Accordingly, the Institute of Medicine recommends thinking in terms of lifelong weight management, encouraging overweight people to try at least to avoid gaining additional weight. According to the report, even small weight losses can raise self-esteem and improve the health of people suffering from obesity-related chronic conditions.

Public health advocates believe that tackling the obesity epidemic will require community-based efforts to increase the availability of healthy foods, changes in national agricultural policy to encourage the availability of nutritious food at a reasonable cost, and regulation of food industry advertising to promote ethical marketing standards.22 A number of proposals have been made to tackle the obesity epidemic with tools similar to those that proved successful in the “tobacco wars.” In addition to the educational campaigns such as the one for “5-A-Day” fruits and vegetables, they include requirements for food labeling and advertising to carry information on calorie, fat, and sugar content and prohibitions on making misleading health claims. Fast-food restaurants should be required to provide nutritional information on packages and wrappers. The nutritionist Nestle proposed taxes on soft drinks and other junk foods to fund “eat less, move more” campaigns and perhaps to subsidize the costs of fruits and vegetables.14(p.367)

Some of these proposals are beginning to be implemented in some places, but they have proved controversial. New York City requires calorie counts to be posted on the menus of fast-food restaurants. The New York State governor, David Paterson, proposed a tax on sugar-sweetened soft drinks and juice drinks as part of his 2009 budget proposal, but the idea met vigorous opposition. When the Maine legislature passed a similar tax, the law was repealed by voters.23 In 2014, Berkeley, California, became the first U.S. city to pass a law taxing sugary drinks.24

Because the impact of lawsuits against tobacco companies was so successful, forcing the companies to raise prices, limiting their advertising and marketing, and publicizing their fraudulent claims, public health advocates are beginning to think about similar lawsuits against fast-food companies. Although a lawsuit against McDonald’s by obese teenagers was laughed out of court, some lawyers see potential for challenging food companies on deceptive advertising and marketing practices, using consumer protection laws. In 2006, the Center for Science in the Public Interest announced a lawsuit against the Kellogg Company and the makers of the television show SpongeBob SquarePants for using the cartoon character to sell sweetened cereals, Pop Tarts, and cookies to children under 8.25 The suit was settled in 2007 with Kellogg agreeing that foods advertised on media targeted at children should meet certain nutrition standards.26 One lawyer who was involved in tobacco cases and is now reportedly preparing suits against food companies is quoted as saying, “The issue is what goes on with the kids, the advertising, what’s in schools. That’s an issue that has some oomph to it.”27

In fact, many public health advocates believe that the best hope of preventing obesity in adulthood is to influence children’s habits. Thus a great deal of attention is being paid to preventing overweight in children. One proven approach is to encourage breastfeeding, which has many other health advantages as well, for both mother and infant. A number of studies have shown that breastfeeding has a long-term protective effect against obesity in children. It also helps the mother to lose weight she gained during pregnancy.28

It is also important to increase parents’ awareness that their children are at risk and for children themselves to be aware of their weight status. In a follow-up to the 1988–1994 NHANES survey, after children were weighed and measured, mothers were asked whether their child was overweight, underweight, or about the right weight. Nearly one-third of mothers of overweight children ages 2 to 11 reported that their child was about the right weight.29 In the 2007–2010 NHANES survey, parental perceptions were even less accurate. Among parents of overweight (but not obese) 8- to 15-year-olds, only 21 percent correctly identified their child’s weight category.30 The 2005–2012 NHANES survey asked 8- to 15-year-old children about their own weight. Among overweight boys, 81 percent said they were about the right weight, while 71 percent of overweight girls reported their weight was about right.31 The state of Arkansas addressed this problem by mandating that schools send home weight report card, and a number of other states and school districts have followed suit, although the practice is controversial because of concerns about stigma.32 It is clear, however, that efforts to prevent and treat childhood obesity must involve parents. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that doctors should measure and chart children’s BMI at least once a year.33 However, a 2002 study found that fewer than 10 percent of practitioners follow all the guidelines.34 Many pediatricians feel unprepared to educate the parents on what to do if their child is overweight.

In 2005, the Institute of Medicine published a report called Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance.35 Calling childhood obesity a “critical public health threat,”35(p.2) the report recommends steps that federal, state, and local governments should take to make prevention of obesity in children and youth a national priority. Recommendations include developing guidelines for advertising and marketing of foods and beverages to children and giving the Federal Trade Commission authority and resources to monitor compliance. The report notes that “more than 50 percent of television advertisements directed at children promote foods and beverages such as candy, fast food, snack foods, soft drinks, and sweetened breakfast cereals that are high in calories and fat, low in fiber, and low in nutrient density.”35(p.172) It also recommends that governments should develop and implement nutritional standards for all foods and beverages sold or served in schools. Food and beverage companies have invaded schools with vending machines selling unhealthy drinks and snacks, fast food in school cafeterias, and special educational programs and materials accompanied by advertisements for fast food and junk food.

As discussed later in this chapter, obesity and chronic disease are as much a result of lack of physical activity as they are of unhealthy diets. Weight-loss programs are most successful, in adults as well as in children, when they combine diet and exercise. “Exercise is today’s best buy in public health,” one commentator notes. “It is positive and acceptable, has insignificant side effects, and can be inexpensive.”36(p.252)

Physical Activity and Health

Most studies on how to lose weight have found that the most effective approach combines dieting and physical activity. Dieters who are physically active are more likely to lose fat while preserving lean mass. This combination not only promotes a healthier distribution of body weight (a lower WHR), but it also helps people avoid the weight loss plateaus that can result from dieting. Since lean mass burns more calories than fat burns, a dieter who loses muscle mass will end up with a higher proportion of his or her weight consisting of fat, and thus fewer calories will be needed to maintain the new weight, making it more difficult to lose additional pounds. Exercising when dieting helps to ensure that the weight lost will be fat. Raising the amount of physical activity without reducing calorie intake, while a relatively inefficient way to lose pounds, is likely to reduce the waist-to-hip ratio and thus improve health.37

A number of epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that people who are more physically active live longer. For example, a study of almost 17,000 male Harvard alumni found that those who engaged in vigorous activities for three or more hours per week were less than half as likely to die within the 12- to 16-year follow-up period than those who had the lowest activity levels.38 Among Harvard graduates who were sedentary at the beginning of the study, those who took up moderate sports activity at some time during the follow-up period had a 23 percent lower death rate than those who remained sedentary.39

Exercise clearly protects against cardiovascular disease, as demonstrated by epidemiologic studies and through biomedical evidence. The Framingham Study found, as early as the 1970s, that the risk for both men and women of dying from cardiovascular disease was highest among those who were the least physically active and that more activity was associated with lower risk.40 Exercise offers protection against both heart disease and stroke. Several studies have indicated that inactive men and women are more likely to develop high blood pressure than those who are active and that moderate intensity exercise may help reduce blood pressure in people whose pressure is elevated.41

There is some biomedical evidence for how physical activity protects against cardiovascular disease. One major factor is the effect on blood cholesterol, especially the tendency for exercise training to increase levels of high-density lipoprotein, “the good cholesterol.” Even a single episode of physical activity has been found to improve the balance of blood lipids, an effect persisting for several days.42 By lowering cholesterol levels in the blood, exercise protects against atherosclerosis. Studies on monkeys have demonstrated that exercise has a protective effect even when the animals are fed a diet high in cholesterol and fats.43 Other favorable effects of physical activity on the cardiovascular system include a lowering of blood pressure, an increase in circulation to the heart muscle, and a reduced tendency of blood to form clots. Moreover, physical activity reduces the risk of diabetes, which is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Type 2, or adult-onset diabetes is related to weight gain in adults, especially weight gain distributed in an “apple” shape, a consequence of insufficient physical activity. The high prevalence of obesity among Americans contributes to the ranking of diabetes as the seventh leading cause of death, probably an underestimate because many cardiovascular deaths have diabetes as an underlying cause.

Early suspicions that physical inactivity contributed to diabetes were raised by observations that prevalence of the disease was higher in societies or groups that moved from a traditional lifestyle to a more technologically advanced environment. This transition has been extensively studied in certain American Indian and Pacific Islander communities. While the increased risk stems in part from changes in diet and increased prevalence of obesity, physical activity may be an independent risk factor.44 The Nurses’ Health Study and the Physicians’ Health Study have both found that regular physical exercise reduces the incidence of type 2 diabetes.45,46 The protective effect of exercise against the development of diabetes seems to work largely by increasing the sensitivity of muscle and other tissues to insulin.

There is also evidence that physical activity protects against cancer, especially colon cancer and breast cancer. Some studies suggest a protective effect against cancer of the lung, prostate, and uterine lining. Exercise also improves survival and quality of life among individuals who have been diagnosed with several kinds of cancer.47

How Much Exercise Is Enough, and How Much Do People Get?

In 2006, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services decided that guidelines for physical activity should be developed, similar to the dietary guidelines. Together with the Institute of Medicine, it undertook a process similar to that used to develop the dietary guidelines. An advisory committee was appointed, which conducted an analysis of the scientific information, held a series of meetings, and released a report in 2008.48

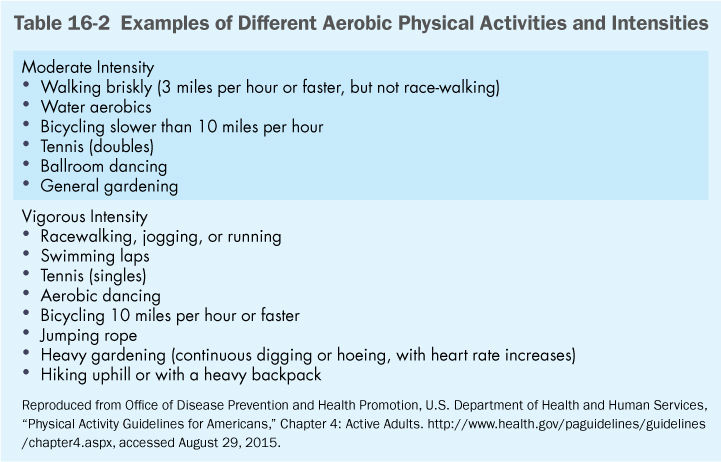

Separate guidelines were developed for children and adolescents (60 minutes or more daily) and adults (at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity). Adults gain increased benefits from 300 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 150 minutes of vigorous activity. Adults should also do muscle strengthening exercise two days a week. Older adults and people with disabilities or chronic medical conditions should do as much as they are able, in consultation with their doctor. Examples of moderate and vigorous activities are shown in (Table 16-2).

In fact, 46.5 percent of American adults report that they met neither the aerobic nor the muscle-strengthening activity guidelines during their leisure time, according to the 2013 National Health Interview Survey.1(Table 63) Lack of activity is more common in females than males and more common in blacks and Hispanics than whites. People with less education and lower incomes are more likely to be inactive than those of higher socioeconomic status, and older adults tend to be more inactive than younger ones.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree