KEY TERMS

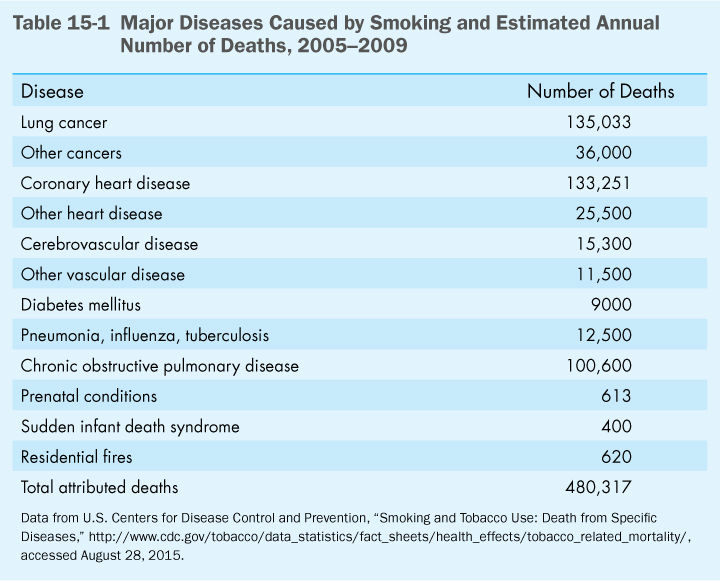

Cigarette smoking—the leading actual cause of death in the United States—is clearly the nation’s most significant public health issue. The problem of tobacco-caused disease embodies the complex interactions by which psychological, social, cultural, economic, and political factors influence individual behavior to cause over 480,000 deaths each year. (Table 15-1) lists the major diseases known to be caused by smoking and estimates the annual number of deaths from each disease. In fact, a more recent analysis concluded that smoking increases the risk of dying from several additional diseases, meaning that the total annual number of deaths attributable to smoking amounts to approximately 540,000.1

The struggle to understand and deal with tobacco-caused illness involves all areas of public health. Epidemiology provided the first solid evidence that smoking caused cancer and heart disease and has continued to yield information on the health effects of this very human habit. Biomedical studies were slow to provide evidence because laboratory animals could not be persuaded or forced to smoke cigarettes, but eventually they yielded valuable information on the role of tobacco in the causation of cancer and heart disease. In recent years, smoking has increasingly been seen as an environmental health threat, producing indoor air pollution that has been shown to cause adverse health effects in nonsmokers. Ultimately, however, smoking is a behavior, and it is the social and behavioral sciences that must provide insights into why people smoke and how they can be persuaded to quit.

Public health faces a fundamental dilemma in confronting the current epidemic of tobacco-caused disease: What should be the role of a democratic government in confronting a behavior that is practiced by nearly one out of five adults and will kill up to half of them? Political and economic forces that favored tobacco have opposed strong government measures against cigarettes. Public health efforts involving education and health promotion campaigns have persuaded many people to stop smoking but seem to have reached the limit of their effectiveness in bringing smoking prevalence down to about 18 percent among adults.2

However, the 1990s saw a major shift in federal and state governments’ attitudes toward smoking. Recognition that the nicotine in tobacco is addictive, together with evidence that cigarette companies have purposely manipulated nicotine levels in cigarettes to keep people hooked, has forced politicians to look with suspicion on what was previously considered a freely chosen behavior. Moreover, evidence of the high economic costs paid by government-financed programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, for the treatment of tobacco-caused disease has forced governments to question their previous assumptions about the economic advantages of supporting the tobacco industry.

Biomedical Basis of Smoking’s Harmful Effects

The basic fact underlying the popular success of cigarettes is that they deliver nicotine, an addictive drug. Nicotine is absorbed by the linings of the mouth and the respiratory tract and travels rapidly to the heart and then to the brain. The drug produces a sense of enhanced energy and alertness, while also having a calming effect on addicted smokers. When people try to quit smoking, they experience withdrawal reactions with unpleasant physical and psychological symptoms. In 2010, 52.4 percent of smokers reported that during the past year they had tried to quit; only about 12 percent of them succeeded.3

In addition to nicotine, an important component of tobacco smoke is tar, the residue from burning tobacco that condenses in the lungs of smokers. Tars provide the flavor in cigarette smoke; they are also a major source of its carcinogenicity. As early as the 1930s, experiments were done in which these tars were painted on the ear linings of rabbits or the shaved backs of mice and found to cause tumors. Decades of studies by biomedical researchers—and clandestinely by tobacco companies, which did not wish to publicize their results—have confirmed the carcinogenicity of the tars as well as other ingredients of the smoke, including arsenic and benzene. When filters were added to cigarettes with the ostensible purpose of removing tars and other harmful ingredients, it turned out that they tended also to remove the taste and “satisfaction” from smoking. Thus filter cigarettes, to be acceptable to smokers, had to deliver significant levels of tar and nicotine, meaning that there were limits to how “safe” a cigarette could be.

Tars not only cause cancer but also contribute to other lung diseases through their tendency to damage cilia, the tiny hairs on the linings of the respiratory tract that sweep the lungs and bronchi clear of microbes, irritants, and toxic substances. Damage to cilia and irritation of respiratory tract linings by components of smoke increase susceptibility to infectious diseases like bronchitis, influenza, and pneumonia as well as to diseases brought on by chronic irritation such as emphysema and asthma.

In contrast to the long-term processes leading to cancer and emphysema, the effect of smoking on the cardiovascular system can be very rapid. The nicotine in cigarette smoke raises blood pressure and heart rate. It may also cause spasms in the blood vessels of the heart, especially if damage already exists, increasing the risk of sudden cardiac death. Carbon monoxide in cigarette smoke interferes with the oxygen-carrying capacity of red blood cells, leading to oxygen shortages in the hearts of patients suffering from coronary artery disease. Smoking increases the risk of stroke and heart attacks by altering the clotting properties of blood. Components of cigarette smoke also have been shown to raise total blood cholesterol levels and reduce levels of HDL, the “good” cholesterol.

Historical Trends in Smoking and Health

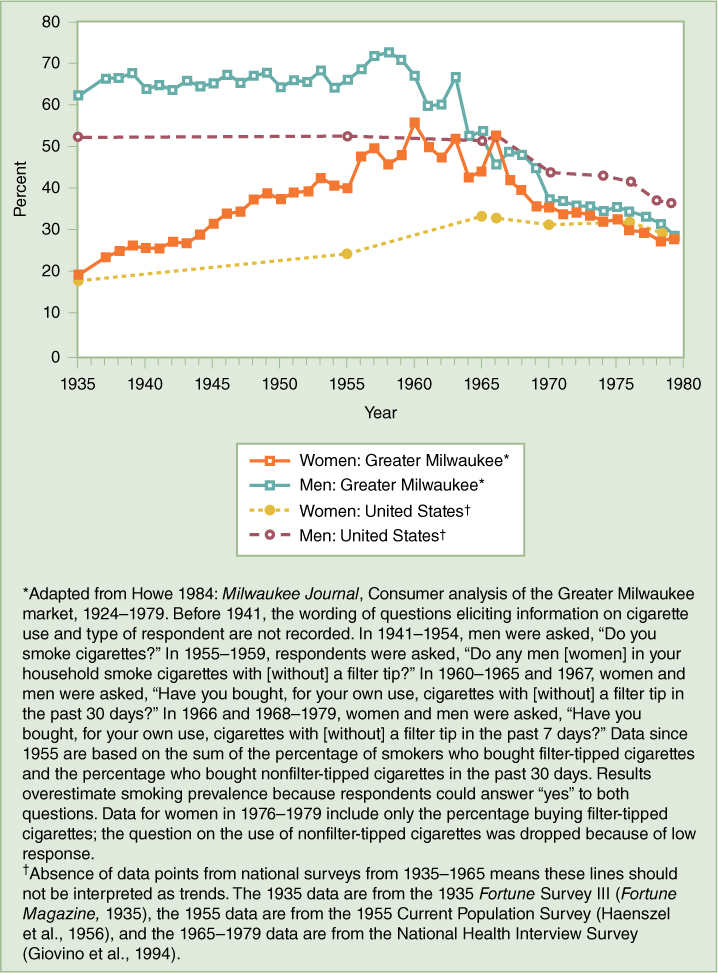

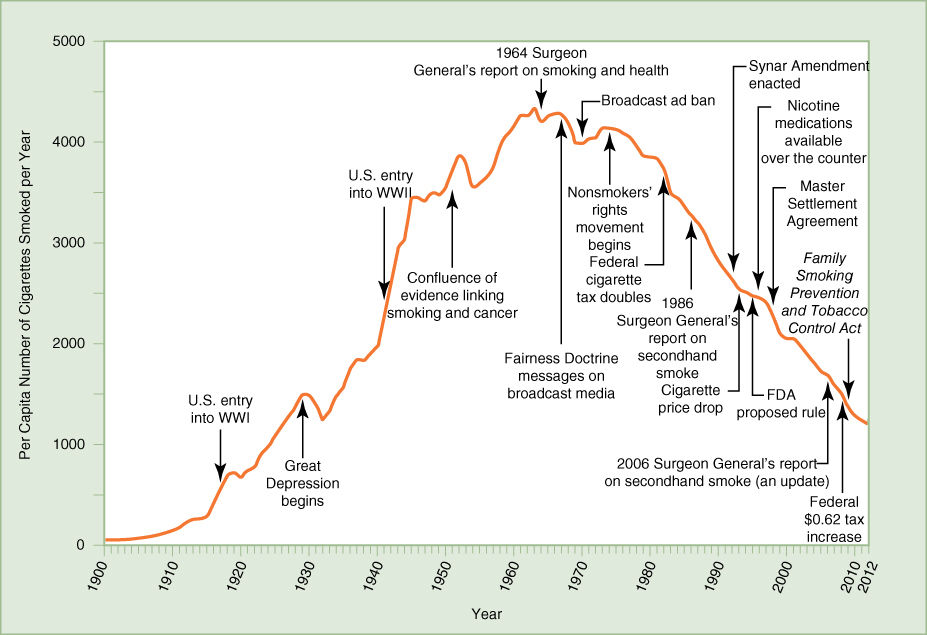

Although it has been smoked and chewed for hundreds of years, tobacco was not used intensively enough to cause widespread illness until the 20th century. Before then, almost all tobacco was smoked in pipes and cigars or used as chewing tobacco and snuff. Cigarette rolling machines and safety matches were invented in the 1880s, but cigarette smoking began to increase dramatically only after 1913, when Camel, followed by other brands, began mass marketing campaigns.3 The distribution of free cigarettes to soldiers during the two world wars further stimulated smoking among men. Smoking among women was frowned on early in the century, but women began to take up the habit during and after World War II, and by 1960 about 34 percent of American women smoked.4 While estimates of the percentage of men and women who smoked during the early part of the century are imprecise [they were done before the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began systematic surveys of the population in 1965], a general idea of the trends in much of the century can be seen in (FIGURE 15-1). The percentage of Americans who smoke has continued to decline since 1980. A better sense of the extent of smoking in this country, and the circumstances influencing it comes from U.S. Department of Agriculture data on total manufactured cigarette consumption, as shown in (FIGURE 15-2).

The first disease clearly linked to smoking was lung cancer, which is caused predominately by smoking and is relatively rare in nonsmokers. Lung cancer was virtually nonexistent in the United States and Britain in 1900. In the 1930s, the increase in deaths from lung cancer began to attract attention, and a link to cigarette smoking began to be suspected. This link was confirmed in the epidemiologic studies published in the 1950s. Cigarette consumption dropped as a result of these reports (as shown in Figure 15-2) but began to climb again when tobacco companies promoted filter cigarettes as a safer alternative.

In 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General released a report, Smoking and Health, a summary of the evidence to date, the result of an exhaustive deliberation by a panel of ten renowned scientists.5 The panel unanimously agreed and wrote that cigarette smoking caused lung cancer and chronic bronchitis and was strongly associated with cancer of the mouth and larynx. It also reported that smoking increased the risk of heart disease. The Surgeon General’s report was very influential, convincing many smokers to quit and providing ammunition for advocates wishing to impose controls on the tobacco industry.

Women were hardly mentioned in the 1964 Surgeon General’s report. Lung cancer was rare in women, and all the studies had been done on men. However, women soon began to catch up. In 1980, the Surgeon General issued another report that focused entirely on women. Health Consequences of Smoking for Women addressed “the fallacy of women’s immunity.”6 The report points out that the first signs of an epidemic of smoking-related diseases among women were just beginning to appear, because women had only begun smoking intensively 25 years after men had. Indeed, lung cancer was about to surpass breast cancer and become the leading cause of cancer death in women, as it is today.7 The report noted that, in addition to suffering the same ill health effects as men, female smokers are at increased risk for complications of pregnancy and that infants of female smokers are more likely to be premature or lagging in physical growth.

Historically, the prevalence of smoking among black men was higher than that for white men; accordingly, lung cancer mortality rates have been higher among black men. Rates of smoking among blacks have declined and are now slightly lower than those among whites. American Indians and Alaskan Natives smoke at much higher rates than other ethnic groups, averaging 19.1 percent overall. Very large differences in smoking rates are seen among groups of different socioeconomic status, and there is a particularly strong association with lack of education. Prevalence of smoking is only about 7.7 percent among male and female college graduates, while 25.8 percent of those without high school diploma are smokers.8

FIGURE 15-1 Prevalence (%) of Current Smoking Among Adults Aged 18 Years or Older in the Greater Milwaukee Area and in the General U.S. Population, by Gender 1935–1979

Reproduced from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001). “Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2001,” Figure 2.1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44311/#A6558, accessed September 20, 2015.

FIGURE 15-2 Annual Adult per Capita Cigarette Consumption, United States, 1900–2012

Reproduced from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, Figure 2.1, 2014. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf, accessed September 20, 2015.

Regulatory Restrictions on Smoking—New Focus on Environmental Tobacco Smoke

Public health efforts at discouraging smoking have had to contend with the enormous economic and political power of the tobacco industry. Congress, which until recently provided subsidies to tobacco growers, has been very reluctant to pass legislation opposed by the industry. However, the 1964 Surgeon General’s report carried great credibility, and its publication led to a number of government actions aimed at restricting cigarette marketing. These included Federal Trade Commission requirements that cigarette packages contain warning labels and a Federal Communications Commission mandate in 1968 that radio and television advertisements for cigarettes be balanced by public service announcements about their harmful effects. The latter requirement, called the Fairness Doctrine, was so effective in countering the tobacco companies’ ads, as seen in the drop in cigarette consumption shown in Figure 15-2, that in 1971 the industry submitted to a total ban on cigarette advertising on radio and television. In return, the public service announcements ceased. The tobacco companies shifted their advertising efforts to magazines, newspapers, billboards, product giveaways, and sponsorship of sporting and cultural events.4

Over the past four decades, new awareness of the harm caused by “second-hand smoke” has led to some of the most effective actions against smoking. Studies began to show that exposure to environmental tobacco smoke caused some of the same health problems as active smoking. For example, the nonsmoking spouses of smokers have an increased risk of lung cancer and heart disease, and children of parents who smoke are more likely to suffer from asthma, respiratory infections, and sudden infant death syndrome. In 1992, the Environmental Protection Agency issued a report that declared environmental tobacco smoke to be a carcinogen, causing 3000 lung cancer deaths a year.9 Evidence of the harm caused by passive smoking inspired the non-smokers rights movement, which largely bypassed the Congress and focused political pressure on state and local governments.

In 1974, Connecticut was the first state to enact restrictions on smoking in restaurants. Minnesota passed a comprehensive statewide clean indoor air law in 1975. In 1983, San Francisco passed a restrictive law against smoking in the workplace, including private workplaces. The clean indoor air movement blossomed. At the state level, laws were passed that restricted smoking on public transit and in elevators, cultural and recreational facilities, schools, and libraries. Over the objections of the tobacco industry, a ban on smoking on all domestic airline flights was passed by Congress in 1989.4 Restrictions on indoor smoking became more widespread in the 1990s. By January 1, 2015, 28 states and the District of Columbia had banned or severely restricted smoking in all public places, including work sites, restaurants, and most bars. All other states had enacted some limitations on indoor smoking, although Wyoming was the least restrictive, with restrictions applied only to government offices, not schools. Many counties and municipalities have passed legislation to promote clean indoor air.10

The effectiveness of the nonsmokers’ rights movement stems from its success in transforming smoking into a socially unacceptable activity. Bans in so many public places force smokers to refrain for extended periods and to segregate themselves when they wish to smoke, often by going outdoors. By making smoking inconvenient, bans encourage people to quit. As Figure 15-2 shows, cigarette consumption has declined steadily since the nonsmokers rights movement began.

Advertising—Emphasis on Youth

While smoking rates among adults have fallen, public health advocates are especially concerned about smoking among youth. Teenagers tend to be less worried about their health in the distant future than they are with their image and social status among their peers. Tobacco companies exploit those concerns in their attempts to win over young people to smoking.

In order to maintain a constant number of customers over time, the tobacco industry must persuade 2 million people to take up the habit each year to balance the number of smokers who die or quit.11 Cigarette advertising and promotional expenditures amounted to $9.2 billion in 2012.12 Because the teen years are the critical period for smoking initiation—90 percent of adult smokers started when they were teenagers, and the average age at which they took up the habit is 14.5—tobacco companies have targeted their advertising toward children and young people.4 For example, Joe Camel ads were strongly appealing to children. A 1991 study found that 91 percent of 6-year-olds recognized the cartoon character, the same percentage that recognized the Mickey Mouse logo of the Disney channel. Some 98 percent of high school students recognized Joe Camel, compared with only 72 percent of adults.13 Between 1988, when the Joe Camel ad campaign was introduced, and 1990, it is estimated that Camel cigarette sales to minors went from $6 million to $476 million.4 In response to an outburst of negative publicity and public anger at the tobacco companies, Joe Camel was retired in 1997.

Tobacco companies also targeted youth with promotional items, such as T-shirts, caps, and sporting goods bearing a brand’s logo. They managed to evade the ban on broadcast advertising by sponsoring sporting events, at which brand names were displayed in the background, ensuring that they would be visible on television throughout the event.

As part of the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA), discussed later in this chapter, major tobacco companies agreed to stop advertisements targeted at children, including some promotional activities. Although the most blatant appeals to youth are gone, the companies began running ads that, while ostensibly antitobacco public service ads, were actually more sophisticated messages designed to encourage youth smoking.14 The messages were that smoking is for adults only, and that parents should talk to their children about not smoking. Analyses of their impact on teens have shown that these ads were ineffective in discouraging young people from smoking and may have increased their intention to smoke. This may have been the intention when the ads were designed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree