KEY TERMS

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

The U.S. population is getting older. The “baby-boom” generation, the oldest of whom are well over 65, is in the process of retiring. The situation is causing great alarm among health planners because of the increasing pressure it places on medical costs. Medicare spending has grown dramatically since the program began, both because of growing medical care costs and because of the aging population. Politicians know that they must do something to remedy the situation, but there is no agreement on how or on what should be done.

Older people tend to be in poorer health than younger ones. They tend to have more chronic illness, and they are more likely to suffer limitations on their ability to participate fully in the activities of their community. These truths have two unhappy consequences: The quality of life of the elderly is, on average, poorer than that for younger people, and their medical costs are higher. Both issues are of great concern for public health.

Quality of life in later years depends significantly on lifestyle in youth and middle age. Therefore, to the extent that public health succeeds in promoting healthy behavior throughout life, there is a payoff in improved health and quality of life for older people. Public health must also address the inevitability that there will be limits to society’s willingness to pay the medical costs of the aged. Although the Medicare program was created in the hope of enabling all older people to receive adequate care, financial barriers are increasing and, like the system as a whole, medical care for the elderly is being rationed. The challenge for public health is twofold: first, to improve the health of older people by prevention of disease and disability; and second, to confront the issue of how costs can be controlled in an equitable and humane way. Although these public health goals for older people are no different from those for other age groups, there is special urgency in the case of the elderly because society has made a unique commitment to this group through the Social Security and Medicare programs, a commitment that is now under stress.

The Aging of the Population—Trends

The population is getting older by a number of measures. The median age of the American population—the age at which half the population is younger and half older—increased from 22.9 in 1900 to 37.2 in 2010 and is predicted to reach 39.6 by 2030.1 In 2010, 13 percent of the population was 65 and over. As the baby-boom cohort grows rapidly, the number of people over 65 will double in size, reaching almost 73 million, or 20.3 percent of the population by 2030. The increased number of older people was accompanied by an increase in life expectancy at birth, from 47.3 in 1900–1902 to 78.7 in 2010.1 Centenarians have increased from 37,000 in 1990 to more than 55,000 in 2010.2,3

As people are living longer, most people aged 65 —the traditional retirement age—are still relatively vigorous. To reflect this reality, the elderly are categorized into three component groups, which have quite different characteristics and needs: the “young old,” ages 65 to 74; the “aged,” who are 75 to 84; and the “oldest old,” those 85 and older. In 2010, there were 5.5 million oldest-old people in the United States, and this is the fastest growing age group in the population other than the baby boomers.1 The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that there will be about 9 million people age 85 and older by the year 2030.1 Obviously these projections have important implications for the Social Security and Medicare systems, because the numbers of working-age people—who will be expected to pay to support the elderly—are growing at much slower rates.

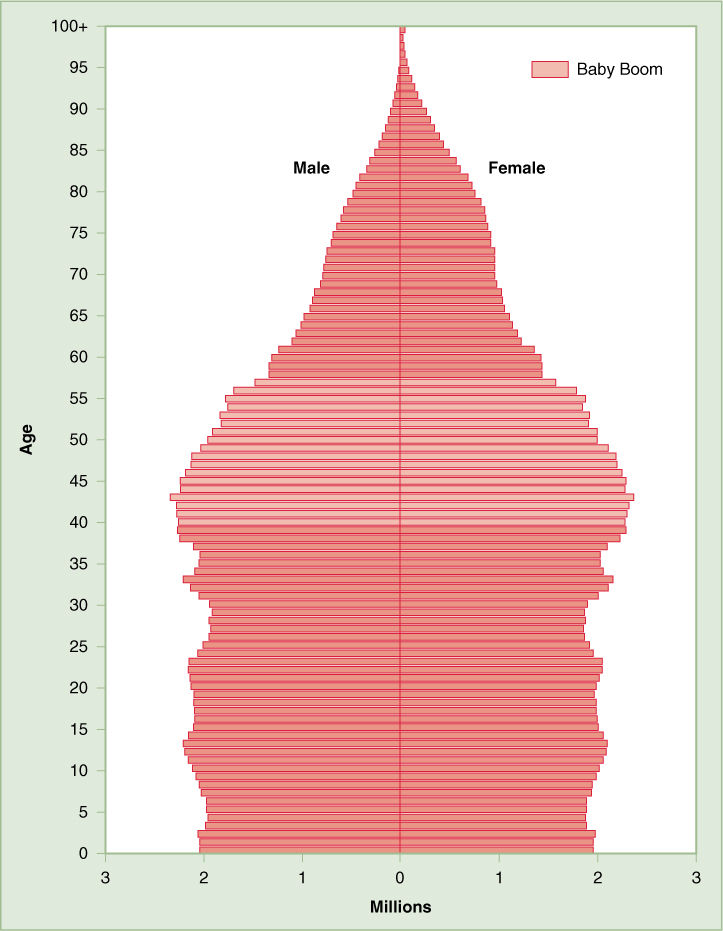

(FIGURE 29-1) shows the age distribution of the population in 2010. The baby-boom generation—those born between 1946 and 1964—is making its way through the age groups like the proverbial pig through a python and accounts for an explosive increase in the numbers of elderly that began in 2011. Predictions of future population size depend both on the birth rate—which is currently fairly stable—and immigration rates, which are somewhat unpredictable and depend on federal policies.

Females increasingly outnumber males in older age groups. Among the oldest old, there are more than twice as many women as men. This is a consequence of the fact that women have a longer life expectancy than men, although the difference is decreasing. After the age of 75, most women are widowed and live alone, while most men are married and live with their wives. Racial and ethnic diversity among the elderly is expected to increase: Non-Hispanic whites constituted 80 percent of the older population in 2010, but that proportion is projected to shrink to 58 percent in 2050. The proportion of Hispanics will grow to 20 percent; blacks will be 12 percent; and Asians will be 8.5 percent. As in younger age groups, older whites are in better health than older people of racial and ethnic minorities. Life expectancy at age 65 is 1.6 years longer for whites than for blacks. However, racial differences in health grow smaller in the oldest populations, and blacks who survive to join the oldest-old category have a slightly longer life expectancy than whites of the same age.4

FIGURE 29-1 U.S. Population by Age and Sex, 2010

Reproduced from U.S. Census Bureau, “2010 Census Briefs: Age and Sex Composition: 2010,” Figure 2, May 2011. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf, accessed September 27, 2015.

Social Security and Medicare have helped most of the older population to stay out of poverty. The percentage of people 65 and older living in poverty declined from 15 percent in 1974 to about 9 percent in 2010. Elderly women (11 percent) were more likely to be poor than elderly men (7 percent). Poverty rates were higher for older blacks (18 percent) and Hispanics (18 percent) than for whites (7 percent).4 The percentage of the general population that have a high school diploma increased from 24 percent in 1965 to 80 percent in 2010; college graduates increased from 5 percent to 22 percent. This increased level of education is generally expected to be correlated with greater health.

Health Status of the Older Population

The greatest public health concern for Americans over 65 is long-term chronic illness, disability, and dependency. The majority of the older population, especially those in the younger groups, are in good health. In national surveys of noninstitutionalized persons, about 82 percent of the young old who are white consider their health to be good to excellent, as do about 76 percent of those 75 to 84 and 69 percent of those 85 and over. Blacks and Hispanics report poorer health than whites. With more advanced age, many older people have chronic conditions that cause them to require assistance with the activities of daily living. Overall, less than 1 percent of people 65 to 75 live in nursing homes, but that proportion increases to about 12 percent of the oldest old.4

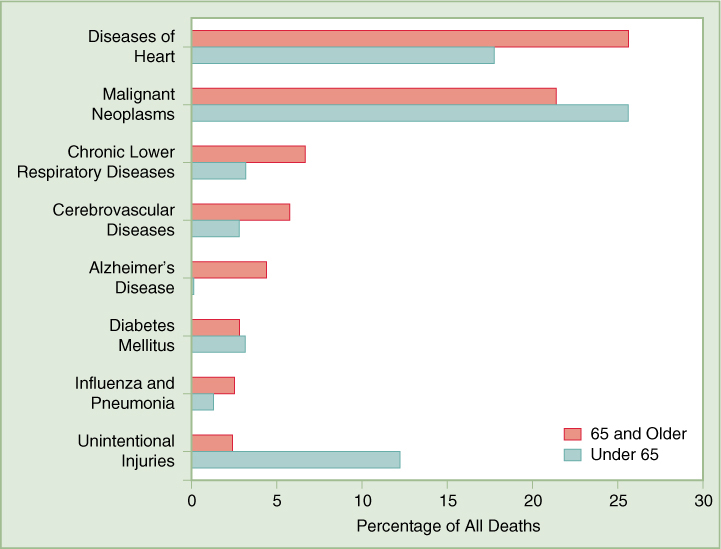

The causes of death of older people are pretty much the same as the causes of death in the overall population, with cardiovascular disease and cancer leading the list (FIGURE 29-2). Motor vehicle crashes and suicide are also significant causes of death, among older men far more than older women. Men are likely to die at a younger age, whereas older women are more likely to suffer from chronic, disabling diseases. Heart disease, cancer, and stroke, in addition to killing people, can contribute to chronic health problems and dependency. Many of the elderly, especially women, suffer from arthritis, diabetes, osteoporosis, and Alzheimer’s disease, conditions that limit their independence and may force them into nursing homes.

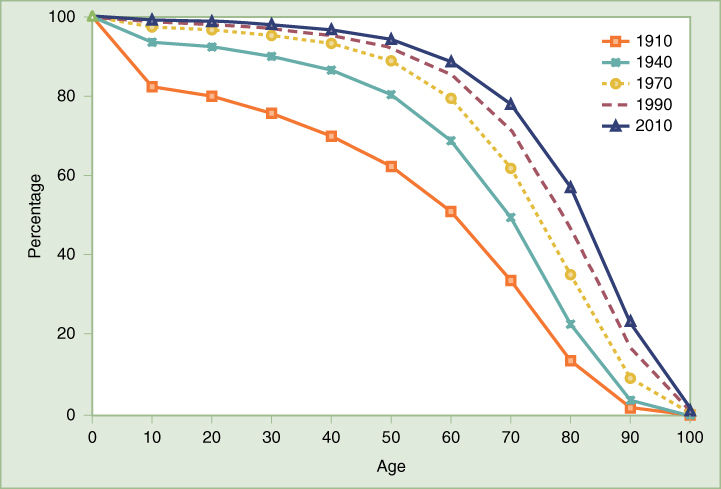

A still unanswered question with very important implications for public health is whether longer life expectancy means more healthy years for most people or, alternatively, if it leads to longer periods of chronic illness and disability. The financial solvency of the Medicare system will be highly dependent on the answer. Experts on aging agree that the trend of the 20th century has been a “compression of mortality,” shown in (FIGURE 29-3), meaning that deaths are increasingly concentrated in a relatively short age range at about the biological limit of life span. What is less certain is whether the compression of mortality will be accompanied by a compression of morbidity—the rates of chronic disease and disability. Ideally most people would prefer to live a long, healthy life and then suddenly drop dead, like the “wonderful one-hoss shay,” a scenario that would also save massive amounts of Medicare money.

Evidence is beginning to emerge that a compression of morbidity is indeed taking place.5 An ongoing national survey of Medicare recipients indicates that disability rates among those over 65 declined steadily, from 26.5 percent in 1982 to 19.0 percent in 2004.6 Other national surveys have had similar findings. Surveys by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have shown that the percentage of older people living in nursing homes declined significantly between 1977 and 2004, especially for whites.7 The Framingham Heart Study, which tracked the health of a cohort of original participants and their offspring, found that the younger generation had less disability than their parents at the same ages.8 On the other hand, the prevalence of many diseases has increased in the older population. For example, chronic cardiovascular disease has become more prevalent as deaths from cardiovascular disease have declined. Having a disease appears to be less disabling than in the past.9 And there is concern that increased obesity in the American population may lead to increased disability rates.

FIGURE 29-2 Leading Causes of Death in U.S. for Individuals Under 65 Years and Individuals 65 Years and Older

Data from National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2014, Tables 20 and 21.

General Approaches to Maximizing Health in Old Age

There is still a great deal to learn about how public health can continue to achieve a compression of morbidity, improving quality of life for those who benefit from the compression of mortality that has already occurred. Although a variety of factors might influence the risk of disability in old age, health-related behavior is one important variable that would be expected to make a difference. A study that tracked 1741 older alumni of the University of Pennsylvania found that, indeed, a healthy lifestyle reduced not only their risk of dying but also their disability in later years. The study subjects, who had attended the University in 1939 and 1940, were surveyed on their smoking habits, body mass index (BMI), and exercise patterns and, beginning in 1986, chronic conditions, use of medical services, and extent of disability. The alumni were classified into three risk groups, the highest risk belonging to obese, inactive smokers. Those in the highest risk group had twice the cumulative disability of those with low risks, and the onset of disability was postponed by almost eight years in the low-risk group.5,10

FIGURE 29-3 Compression of Mortality: percent surviving by age

Modified from Arias E. United States life tables, 2008. National vital statistics reports; vol 61 no 3. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2012, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_03.pdf, p. 48.

This evidence indicates that, as in younger age groups, the behaviors that most significantly affect health in older people are smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity.5 However, the recently observed compression of morbidity cannot entirely be explained by improvements in these factors. The reduced prevalence of smoking over the past several decades is no doubt responsible in part for the fact that the elderly are healthier than they used to be. But the increased prevalence of overweight, obesity, and physical inactivity would be expected to have the opposite effect, leading to increased disability in older people.

Smoking is always a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease and cancer, still the leading causes of death in those over 65. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is caused almost entirely by smoking. Osteoporosis and disorders of the mouth are also made worse by smoking. It is significant that prevalence of smoking drops off with increasing age, in part because many older people have succeeded in quitting and in part because many smokers die before they reach old age. In 2013, only 10.6 percent of American men aged 65 and over smoked. The rate among older women was 7.5 percent.11,Table 52

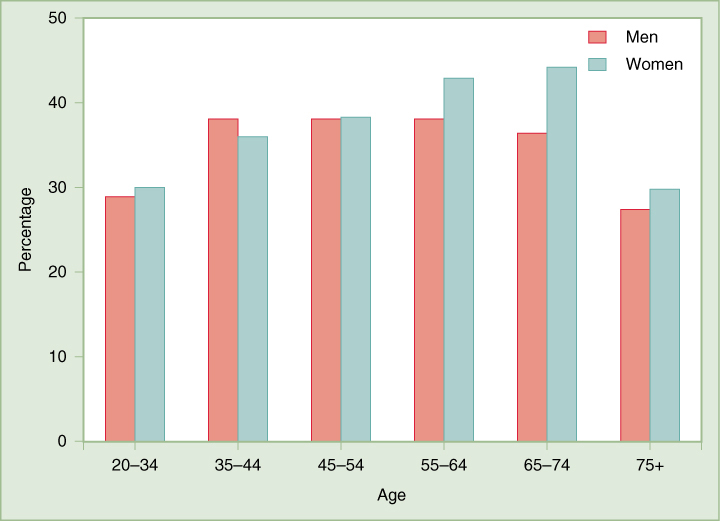

Nutrition and physical activity are the other most important determinants of health in old age. Diet and exercise affect the risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Overweight and obesity, the result of overnutrition and lack of exercise, increase the risk not only of the leading killers, but also of diabetes and arthritis of the weight-bearing joints. Interestingly, the percentage of the population that is overweight and obese decreases after age 75, as seen in (FIGURE 29-4). The reason for this is not known, but one theory is that, like cigarette smokers, obese people die at an earlier age. This may explain in part the apparent paradox between the obesity epidemic and the trend toward better health in the older population. Because obese people are more likely to report poor health than people of normal weight, it is likely that the compression of morbidity seen in recent years will be reversed unless the obesity epidemic can be halted.12 However, some studies suggest that the health effects of obesity in older people may be less harmful.6

Obesity is not the only outcome of poor diet and lack of exercise. Elderly individuals need physical activity to maintain muscle strength, balance, and cardiovascular fitness, which protect them against osteoporosis and falls. The special nutritional needs of the elderly are not well understood, but adequate calcium and vitamin D are clearly important for the strength of bones and teeth. There is little evidence about the special effects of other nutrients in protecting against the diseases of the elderly, and the best advice is, as for younger people, to eat a varied diet low in fat and rich in fruits and vegetables.

FIGURE 29-4 Percentage of U.S. Population Obese by Age and Sex, 2009–2012

Data from National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2014. Table 64.

Through the 1990s, more and more evidence appeared suggesting that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) might have broad health advantages for older women in addition to its well-known efficacy in fending off the symptoms of menopause. A number of epidemiologic studies, including the cohort of 60,000 women in the Nurses’ Health Study, showed that estrogen therapy was associated with lower rates of heart disease and osteoporosis and perhaps Alzheimer’s as well. On the other hand, the hormone increases the risk of breast and uterine cancer. In a 1997 publication, the investigators concluded that HRT reduced women’s overall risk of dying as long as they took the hormones.13 The hopes for estrogen’s anti-aging effects were crushed, however, with the publication of the clinical trial conducted as part of the Women’s Health Initiative. The trial found that although HRT helped to prevent osteoporosis and the symptoms of menopause, it actually increased the risk of heart disease, strokes, and even Alzheimer’s disease. It seems that the apparent benefits of estrogen were caused by the confounding factor that women who chose HRT were healthier and more likely to have a healthy lifestyle than those who chose not to use the hormone.14

Other aspects of medical care have probably contributed to reductions in disability among the elderly. For example, secondary prevention such as the use of drugs to treat diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol have undoubtedly reduced morbidity and mortality in many older people. The number of total knee replacements for arthritis and cataract surgeries doubled over the period of 1991 to 2010, greatly reducing disabilities and improving quality of life.15,16 Still, there are concerns about shortages of healthcare workers, especially those with education and training in caring for older adults. According to a 2008 report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM), older adults, 12 percent of the population, account for approximately 26 percent of all physician office visits, 35 percent of hospital stays, 34 percent of prescriptions, and 38 percent of emergency medical service responses. The IOM predicts that the current workforce is not large enough to meet the needs of the growing number of elderly.17

Preventing Disease and Disability in Old Age

Much of the disease and disability common in later life is linked to unhealthy behavior in earlier years. However, there are preventive measures that the elderly and their caregivers can take to improve their quality of life and prospects for independence even after health has begun to fail. Some of these measures are well known and easily available, such as vaccination against pneumonia and influenza. Some are beneficial and appropriate for people of any age, such as smoking cessation and blood pressure control. Others are not widely recognized or well understood. Research is needed on how to prevent many of the debilitating conditions and how to minimize their impact on quality of life for the elderly. In a 1990 report, the IOM identified a number of the most common problems of the elderly and made recommendations for combating them.18 These problems commonly and uniquely afflict the elderly and have a severe impact on their quality of life but are not among the leading causes of death. Despite the passage of more than 25 years since the IOM report, these difficulties are still causing trouble for older people.

Medications

Although chronic conditions that afflict many of the elderly can be helped by prescription drugs, some of these treatments have unwanted side effects that may seriously impair health and quality of life. Little is known about how the body’s ability to metabolize drugs changes with age. Kidney and liver function are often impaired in older people, leading to increased sensitivity to drugs. In older bodies, a higher percentage of body weight is fat, which metabolizes drugs less actively, causing an increased risk of overdoses. Moreover, older people often take a number of medications for various chronic conditions. This could lead to unexpected interactions between drugs, including over-the-counter drugs, because patients tend not to inform their doctors about these medications.

Reducing the risks from adverse drug reactions requires education and vigilance by everyone involved. Elderly patients’ needs for medications should be reassessed regularly. In some cases, the potential benefit provided by a drug—for example, improved heart function—may not be worth the damage it could cause to other aging organs, for example, the brain. According to the IOM, there is an urgent need for more research on risk versus benefit of various types of drugs in the elderly. There is also a need for better coordination and monitoring of medical care, a need that might be better filled by managed care than by fee-for-service care, which currently dominates in serving the Medicare population.

Osteoporosis

Bone loss is common with age, especially in women. This loss leads to osteoporosis—“porous bones,” which tend to break easily. Bone loss among women is greatest in the years following menopause. Smoking and alcohol consumption increase the risk of osteoporosis; obesity reduces the risk (one of the few health benefits of being overweight). White women have the greatest risk for the condition; black men have the lowest, and Asians have intermediate risk. A number of medications commonly used by older people cause bone loss. Some diseases also cause bone loss. The degree of osteoporosis depends on bone density earlier in life, which is determined by a number of factors including genetics, diet, and physical activity. Thus, drinking milk and exercising during youth can protect women against osteoporosis in old age. Unfortunately, girls tend to not take the threat seriously when these habits could do them the most good. Surveys have found that the average amount of calcium women obtain in their diet is significantly below the recommended amount.19

Osteoporosis itself has no symptoms, and most older people are unaware that they have the problem until they suffer a broken bone. Hip fractures are the most serious consequence of osteoporosis; there is a significant risk that a hip fracture might lead to substantial disability and death. Of those aged 65 or older who suffer a hip fracture, about 20 percent die within a year.19

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree